From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

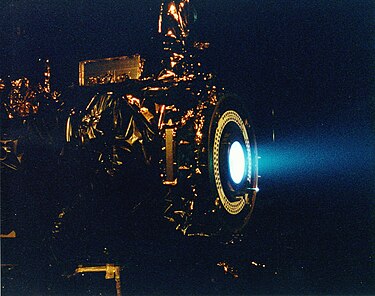

NASA's 2.3 kW NSTAR ion thruster for the Deep Space 1 spacecraft during a hot fire test at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

An ion thruster is a form of electric propulsion used for spacecraft propulsion that creates thrust by accelerating ions. The term is strictly used to refer to gridded electrostatic ion thrusters, but may often more loosely be applied to all electric propulsion systems that accelerate plasma, since plasma consists of ions. Ion thrusters are categorized by how they accelerate the ions, using either electrostatic or electromagnetic force. Electrostatic ion thrusters use the Coulomb force and accelerate the ions in the direction of the electric field. Electromagnetic ion thrusters use the Lorentz force to accelerate the ions. In either case, when an ion passes through an electrostatic grid engine, the potential difference of the electric field converts to the ion's kinetic energy.

According to Edgar Choueiri ion thrusters have an input power spanning 1–7 kilowatts, exhaust velocity 20–50 kilometers per second, thrust 20–250 millinewtons and efficiency 60–80%.[1][2]

The Deep Space 1 spacecraft, powered by an ion thruster, changed velocity by 4.3 km/s while consuming less than 74 kilograms of xenon. The Dawn spacecraft has surpassed the record with 10 km/s.[1][2]

The applications of ion thrusters include control of the orientation and position of orbiting satellites (some satellites have dozens of low-power ion thrusters) and use as a main propulsion engine for low-mass robotic space vehicles (for example Deep Space 1 and Dawn).[1][2]

Ion thrusters are not the most prospective type of electrically powered spacecraft propulsion (although in practice they have worked out more than others).[2] Real ion engine on the technical characteristics (and especially on the thrust) is considerably inferior to his literary prototypes (according to Edgar Choueiri — «hardly the thundering rocket engine of sci-fi movies and more akin to a car that takes two days to accelerate from zero to 60 miles per hour»).[1][2] Technical capabilities of the ion engine are limited by the space charge created by ions, that limits the thrust density (force per cross-sectional area of the engine) to a very small level.[2] Therefore ion thrusters create very small levels of thrust (for example the thrust of Deep Space 1's engine approximately equals the weight of one sheet of paper[2]) compared to conventional chemical rockets but achieve very high specific impulse, or propellant mass efficiency, by accelerating their exhaust to very high speed.

However, ion thrusters carry a fundamental price: the power imparted to the exhaust increases with the square of its velocity while the thrust increases only linearly. Normal chemical rockets, on the other hand, can provide very high thrust but are limited in total impulse by the small amount of energy that can be stored chemically in the propellants.[3] Given the practical weight of suitable power sources, the accelerations given by ion thrusters are frequently less than one thousandth of standard gravity. However, since they operate essentially as electric (or electrostatic) motors, a greater fraction of the input power is converted into kinetic exhaust power than in a chemical rocket. Chemical rockets operate as heat engines, hence Carnot's theorem bounds their possible exhaust velocity.

Due to their relatively high power needs, given the specific power of power supplies, and the requirement of an environment void of other ionized particles, ion thrust propulsion is currently only practical on spacecraft that have already reached space, and are unable to take vehicles from Earth to space, relying on conventional chemical rockets to initially reach orbit.

Origins

The first person to publish mention of the idea was Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1911.[4] However, the first documented instance where the possibility of electric propulsion is considered is found in Robert H. Goddard's handwritten notebook in an entry dated 6 September 1906.[5] The first experiments with ion thrusters were carried out by Goddard at Clark University from 1916–1917.[6] The technique was recommended for near-vacuum conditions at high altitude, but thrust was demonstrated with ionized air streams at atmospheric pressure. The idea appeared again in Hermann Oberth's "Wege zur Raumschiffahrt” (Ways to Spaceflight), published in 1923, where he explained his thoughts on the mass savings of electric propulsion, predicted its use in spacecraft propulsion and attitude control, and advocated electrostatic acceleration of charged gases.[4]A working ion thruster was built by Harold R. Kaufman in 1959 at the NASA Glenn Research Center facilities. It was similar to the general design of a gridded electrostatic ion thruster with mercury as its fuel. Suborbital tests of the engine followed during the 1960s and in 1964 the engine was sent into a suborbital flight aboard the Space Electric Rocket Test 1 (SERT 1). It successfully operated for the planned 31 minutes before falling back to Earth.[7] This test was followed by an orbital test, SERT-2, in 1970.

An alternate form of electric propulsion, the Hall effect thruster was studied independently in the U.S. and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. Hall effect thrusters had operated on Soviet satellites since 1972. Until the 1990s they were mainly used for satellite stabilization in North-South and in East-West directions. Some 100-200 engines completed their mission on Soviet and Russian satellites until the late 1990s.[8] Soviet thruster design was introduced to the West in 1992 after a team of electric propulsion specialists, under the support of the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, visited Soviet laboratories.

General description

Ion thrusters use beams of ions (electrically charged atoms or molecules) to create thrust in accordance with momentum conservation. The method of accelerating the ions varies, but all designs take advantage of the charge/mass ratio of the ions. This ratio means that relatively small potential differences can create very high exhaust velocities. This reduces the amount of reaction mass or fuel required, but increases the amount of specific power required compared to chemical rockets. Ion thrusters are therefore able to achieve extremely high specific impulses. The drawback of the low thrust is low spacecraft acceleration, because the mass of current electric power units is directly correlated with the amount of power given. This low thrust makes ion thrusters unsuited for launching spacecraft into orbit, but they are ideal for in-space propulsion applications.Various ion thrusters have been designed and they all generally fit under two categories. The thrusters are categorized as either electrostatic or electromagnetic. The main difference is how the ions are accelerated.

- Electrostatic ion thrusters use the Coulomb force and are categorized as accelerating the ions in the direction of the electric field.

- Electromagnetic ion thrusters use the Lorentz force to accelerate the ions.

Electric thrusters tend to produce low thrust, which results in low acceleration. Using 1 g is 9.81 m/s2; F = m a ⇒ a = F/m. An NSTAR thruster producing a thrust (force) of 92 mN[9] will accelerate a satellite with a mass of 1,000 kg by 0.092 N / 1,000 kg = 0.000092 m/s2 (or 9.38×10−6 g).

Electrostatic ion thrusters

Gridded electrostatic ion thrusters

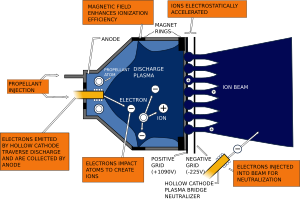

Gridded electrostatic ion thrusters commonly utilize xenon gas. This gas has no charge and is ionized by bombarding it with energetic electrons. These electrons can be provided from a hot cathode filament and when accelerated in the electrical field of the cathode, fall to the anode. Alternatively, the electrons can be accelerated by the oscillating electric field induced by an alternating magnetic field of a coil, which results in a self-sustaining discharge and omits any cathode (radio frequency ion thruster).The positively charged ions are extracted by an extraction system consisting of 2 or 3 multi-aperture grids. After entering the grid system via the plasma sheath the ions are accelerated due to the potential difference between the first and second grid (named screen and accelerator grid) to the final ion energy of typically 1-2 keV, thereby generating the thrust.

Ion thrusters emit a beam of positive charged xenon ions only. To avoid charging up the spacecraft, another cathode is placed near the engine, which emits electrons (basically the electron current is the same as the ion current) into the ion beam.[7] This also prevents the beam of ions from returning to the spacecraft and cancelling the thrust.[citation needed]

Gridded electrostatic ion thruster research (past/present):

- NASA Solar electric propulsion Technology Application Readiness (NSTAR) - 2.3 kW, used on two successful missions

- NASA’s Evolutionary Xenon Thruster (NEXT) - 6.9 kW, flight qualification hardware built

- Nuclear Electric Xenon Ion System (NEXIS)

- High Power Electric Propulsion (HiPEP) - 25 kW, test example built and run briefly on the ground

- EADS Radio-Frequency Ion Thruster (RIT)

- Dual-Stage 4-Grid (DS4G)[10][11]

Hall effect thrusters

Hall effect thrusters accelerate ions with the use of an electric potential maintained between a cylindrical anode and a negatively charged plasma that forms the cathode. The bulk of the propellant (typically xenon gas) is introduced near the anode, where it becomes ionized, and the ions are attracted towards the cathode; they accelerate towards and through it, picking up electrons as they leave to neutralize the beam and leave the thruster at high velocity.The anode is at one end of a cylindrical tube, and in the center is a spike that is wound to produce a radial magnetic field between it and the surrounding tube. The ions are largely unaffected by the magnetic field, since they are too massive. However, the electrons produced near the end of the spike to create the cathode are far more affected and are trapped by the magnetic field, and held in place by their attraction to the anode. Some of the electrons spiral down towards the anode, circulating around the spike in a Hall current. When they reach the anode they impact the uncharged propellant and cause it to be ionized, before finally reaching the anode and closing the circuit.[12]

Field-emission electric propulsion

Field-emission electric propulsion (FEEP) thrusters use a very simple system of accelerating ions to create thrust. Most designs use either caesium or indium as the propellant. The design comprises a small propellant reservoir that stores the liquid metal, a narrow tube or a system of parallel plates that the liquid flows through, and an accelerator (a ring or an elongated aperture in a metallic plate) about a millimetre past the tube end. Caesium and indium are used due to their high atomic weights, low ionization potentials, and low melting points. Once the liquid metal reaches the end of the tube, an electric field applied between the emitter and the accelerator causes the liquid surface to deform into a series of protruding cusps ("Taylor cones"). At a sufficiently high applied voltage, positive ions are extracted from the tips of the cones.[13][14][15] The electric field created by the emitter and the accelerator then accelerates the ions. An external source of electrons neutralizes the positively charged ion stream to prevent charging of the spacecraft.Electromagnetic thrusters

Pulsed inductive thrusters (PIT)

Pulsed inductive thrusters (PIT) use pulses of thrust instead of one continuous thrust, and have the ability to run on power levels in the order of Megawatts (MW). PITs consist of a large coil encircling a cone shaped tube that emits the propellant gas. Ammonia is the gas commonly used in PIT engines. For each pulse of thrust the PIT gives, a large charge first builds up in a group of capacitors behind the coil and is then released. This creates a current that moves circularly in the direction of jθ. The current then creates a magnetic field in the outward radial direction (Br), which then creates a current in the ammonia gas that has just been released in the opposite direction of the original current. This opposite current ionizes the ammonia and these positively charged ions are accelerated away from the PIT engine due to the electric field jθ crossing with the magnetic field Br, which is due to the Lorentz Force.[16]Magnetoplasmadynamic (MPD) / lithium Lorentz force accelerator (LiLFA)

Magnetoplasmadynamic (MPD) thrusters and lithium Lorentz force accelerator (LiLFA) thrusters use roughly the same idea with the LiLFA thruster building off of the MPD thruster. Hydrogen, argon, ammonia, and nitrogen gas can be used as propellant. In a certain configuration, the ambient gas in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) can be used as a propellant. The gas first enters the main chamber where it is ionized into plasma by the electric field between the anode and the cathode. This plasma then conducts electricity between the anode and the cathode. This new current creates a magnetic field around the cathode, which crosses with the electric field, thereby accelerating the plasma due to the Lorentz force. The LiLFA thruster uses the same general idea as the MPD thruster, except for two main differences. The first difference is that the LiLFA uses lithium vapor, which has the advantage of being able to be stored as a solid. The other difference is that the cathode is replaced by multiple smaller cathode rods packed into a hollow cathode tube. The cathode in the MPD thruster is easily corroded due to constant contact with the plasma. In the LiLFA thruster the lithium vapor is injected into the hollow cathode and is not ionized to its plasma form/corrode the cathode rods until it exits the tube. The plasma is then accelerated using the same Lorentz Force.[17][18][19]Electrodeless plasma thrusters

Electrodeless plasma thrusters have two unique features: the removal of the anode and cathode electrodes and the ability to throttle the engine. The removal of the electrodes takes away the factor of erosion, which limits lifetime on other ion engines. Neutral gas is first ionized by electromagnetic waves and then transferred to another chamber where it is accelerated by an oscillating electric and magnetic field, also known as the ponderomotive force. This separation of the ionization and acceleration stage give the engine the ability to throttle the speed of propellant flow, which then changes the thrust magnitude and specific impulse values.[20]Helicon double layer thruster

A helicon double layer thruster is a type of plasma thruster, which ejects high velocity ionized gas to provide thrust to a spacecraft. In this thruster design, gas is injected into a tubular chamber (the source tube) with one open end. Radio frequency AC power (at 13.56 MHz in the prototype design) is coupled into a specially shaped antenna wrapped around the chamber. The electromagnetic wave emitted by the antenna causes the gas to break down and form a plasma. The antenna then excites a helicon wave in the plasma, which further heats the plasma. The device has a roughly constant magnetic field in the source tube (supplied by solenoids in the prototype), but the magnetic field diverges and rapidly decreases in magnitude away from the source region, and might be thought of as a kind of magnetic nozzle. In operation, there is a sharp boundary between the high density plasma inside the source region, and the low density plasma in the exhaust, which is associated with a sharp change in electrical potential. The plasma properties change rapidly across this boundary, which is known as a current-free electric double layer. The electrical potential is much higher inside the source region than in the exhaust, and this serves both to confine most of the electrons, and to accelerate the ions away from the source region. Enough electrons escape the source region to ensure that the plasma in the exhaust is neutral overall.Comparisons

The following table compares actual test data of some ion thrusters:| Engine | Propellant | Required power (kW) |

Specific impulse (s) |

Thrust (mN) |

Thruster mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSTAR | Xenon | 2.3 | 3,300 to 1,700[21] | 92 max.[9] | |

| NEXT[9] | Xenon | 6.9[22] | 4,300 [22][23][24] | 236 max[9] | |

| NEXIS[25] | Xenon | 20.5 | |||

| HiPEP | Xenon | 20–50[26] | 6,000–9,000[26] | 460–670[26] | |

| RIT 22[27] | Xenon | 5 | |||

| Hall effect | Bismuth | 25[citation needed] | |||

| Hall effect | Bismuth | 140[citation needed] | |||

| Hall effect | Xenon | 25[citation needed] | 3,250[citation needed] | 950[citation needed] | |

| Hall effect | Xenon | 75[citation needed] | |||

| FEEP | Liquid Caesium | 6×10−5–0.06 | 6,000–10,000[14] | 0.001–1[14] | |

| VASIMR | Argon | 200 | 3,000–12,000 | ~5,000[28] | 620 [1] |

| DS4G | Xenon | 250 | 19,300 | 2,500 max. | 5 |

| KLIMT | Krypton | 0.5[29] | 4[29] |

The following thrusters are highly experimental and have been tested only in pulse mode.

| Engine | Propellant | Required power (kW) |

Specific impulse (s) |

Thrust (mN) |

Thruster mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPDT | Hydrogen | 1,500 | 4,900[citation needed] | 26,300[citation needed] | |

| MPDT | Hydrogen | 3,750 | 3,500[citation needed] | 88,500[citation needed] | |

| MPDT | Hydrogen | 7,500[citation needed] | 6,000[citation needed] | 60,000[citation needed] | |

| LiLFA | Lithium Vapor | 500 | 4,077[citation needed] | 12,000[citation needed] |

Lifetime

A major limiting factor of ion thrusters is their small thrust; however, it is generated at a high propellant efficiency (mass utilisation, specific impulse). The efficiency comes from the high exhaust velocity, which in turn demands high energy, and the performance is ultimately limited by the available spacecraft power.The low thrust requires ion thrusters to provide continuous thrust for a long time to achieve the needed change in velocity (delta-v) for a particular mission. To cause enough change in momentum, ion thrusters are designed to last for periods of weeks to years.

In practice the lifetime of electrostatic ion thrusters is limited by several processes:

- In electrostatic gridded ion thruster design, charge-exchange ions produced by the beam ions with the neutral gas flow can be accelerated towards the negatively biased accelerator grid and cause grid erosion. End-of-life is reached when either a structural failure of the grid occurs or the holes in the accelerator grid become so large that the ion extraction is largely affected; e.g., by the occurrence of electron backstreaming. Grid erosion cannot be avoided and is the major lifetime-limiting factor. By a thorough grid design and material selection, lifetimes of 20,000 hours and far beyond are reached, which is sufficient to fulfill current space missions.

More recently, the NASA Evolutionary Xenon Thruster (NEXT) Project, conducted at NASA's Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, operated continuously for more than 48,000 hours.[31] The test was conducted in a high vacuum test chamber at Glenn Research Center. Over the course of the 5 1/2 + year test, the engine consumed approximately 870 kilograms of xenon propellant. The total impulse provided by the engine would require over 10,000 kilograms of conventional rocket propellant for similar application. The engine was designed by Aerojet Rocketdyne of Sacramento, California.

- Hall thrusters suffer from very strong erosion of the ceramic discharge chamber by impact of energetic ions: a test reported in 2010[32] showed erosion of around 1 mm per hundred hours of operation, though this is inconsistent with observed on-orbit lifetimes of a few thousand hours.

Propellants

Ionization energy represents a very large percentage of the energy needed to run ion drives. The ideal propellant for ion drives is thus a propellant molecule or atom that is easy to ionize, that has a high mass/ionization energy ratio. In addition, the propellant should not cause erosion of the thruster to any great degree to permit long life; and should not contaminate the vehicle.[33]Many current designs use xenon gas, as it is easy to ionize, has a reasonably high atomic number, its inert nature, and low erosion. However, xenon is globally in short supply and very expensive.

Older designs used mercury, but this is toxic and expensive, tended to contaminate the vehicle with the metal and was difficult to feed accurately.

Other propellants, such as bismuth, show promise and are areas of research, particularly for gridless designs, such as Hall effect thrusters.

VASIMR design (and other plasma-based engines) are theoretically able to use practically any material for propellant. However, in current tests the most practical propellant is argon, which is a relatively abundant and inexpensive gas.

Energy efficiency

Ion thrusters are frequently quoted with an efficiency metric. This efficiency is the kinetic energy of the exhaust jet emitted per second divided by the electrical power into the device.

The actual overall system energy efficiency in use is determined by the propulsive efficiency, which depends on vehicle speed and exhaust speed. Some thrusters can vary exhaust speed in operation, but all can be designed with different exhaust speeds. At the lower end of Isps the overall efficiency drops, because the ionization takes up a larger percentage energy, and at the high end propulsive efficiency is reduced.

Optimal efficiencies and exhaust velocities can thus be calculated for any given mission to give minimum overall cost.

Applications

Ion thrusters have many applications for in-space propulsion. The best applications of the thrusters make use of the long lifetime when significant thrust is not needed. Examples of this include orbit transfers, attitude adjustments, drag compensation for low Earth orbits, transporting cargo such as chemical fuels between propellant depots and ultra-fine adjustments for scientific missions. Ion thrusters can also be used for interplanetary and deep-space missions where time is not crucial. Continuous thrust over a very long time can build up a larger velocity than traditional chemical rockets.Missions

Of all the electric thrusters, ion thrusters have been the most seriously considered commercially and academically in the quest for interplanetary missions and orbit raising maneuvers. Ion thrusters are seen as the best solution for these missions, as they require very high change in velocity overall that can be built up over long periods of time.Pure demonstration vehicles

- SERT

Operational missions

Ion thrusters are routinely used for station-keeping on commercial and military communication satellites in geosynchronous orbit, including satellites manufactured by Boeing and by Hughes Aerospace. The pioneers in this field were the Soviet Union, who used SPT thrusters on a variety of satellites starting in the early 1970s.Two geostationary satellites (ESA's Artemis in 2001-2003[38] and the US military's AEHF-1 in 2010-2012[39]) have used the ion thruster for orbit raising after the failure of the chemical-propellant engine. Boeing[40] have been using ion thrusters for station-keeping since 1997, and plan in 2013-2014 to offer a variant on their 702 platform, which will have no chemical engine and use ion thrusters for orbit raising; this enables a significantly lower launch mass for a given satellite capability. AEHF-2 used a chemical engine to raise perigee to 10150 miles and is then proceeding to geosynchronous orbit using electric propulsion.[41]

In Earth orbit

- GOCE

In deep space

- Deep Space 1

- Hayabusa

- Smart 1

- Dawn

Planned missions

In addition, several missions are planned to use ion thrusters in the next few years.- BepiColombo

- LISA Pathfinder

- International Space Station

Currently, altitude reboosting by chemical rockets fulfills this requirement. If the tests of VASIMR reboosting of the ISS goes according to plan, the increase in specific impulse could mean that the cost of fuel for altitude reboosting will be one-twentieth of the current $210 million annual cost.[45] Hydrogen is generated by the ISS as a by-product, which is currently vented into space.

- NASA high-power SEP system demonstration mission