From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC) was a minor extinction event that occurred around 305 million years ago in the Carboniferous period.[1] It altered the vast coal forests that covered the equatorial region of Euramerica (Europe and America). This event may have fragmented the forests into isolated 'islands', which in turn caused the extinction of many plant and animal species. After the event, coal-forming tropical forests did continue in large areas of the earth, but their extent and composition were changed.

The event occurred at the end of the Moscovian and continued into the early Kasimovian stages of the Pennsylvanian. The CRC can also be viewed as part of a broader transition of plant species called the "Carboniferous-Permian transition" that continued for another 10 million years into the early Permian. This larger transition has been recognized as one of the two largest extinction events for plant life.[2]

Extinction patterns on land

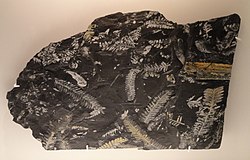

Ferns and treeferns from Mount Field National Park, giving an impression of how a Carboniferous rainforest might have looked.

In the Carboniferous, the great tropical rainforests of Euramerica supported towering lycopsids, a heterogeneous mix of vegetation, as well as a great diversity of animal life: giant dragonflies, millipedes, cockroaches, amphibians, and the first reptiles.

Plants

The rise of rainforests in the Carboniferous greatly altered the landscapes by eroding low-energy, organic-rich anastomosing (braided) river systems with multiple channels and stable alluvial islands. The continuing evolution of tree-like plants increased floodplain stability (less erosion and movement) by the density of floodplain forests, the production of woody debris, and an increase in complexity and diversity of root assemblages.[3]Collapse occurred through a series of step changes. First there was a gradual rise in the frequency of opportunistic ferns in late Moscovian times.[4] This was followed in the earliest Kasimovian by a major, abrupt extinction of the dominant lycopsids and a change to tree fern dominated ecosystems.[5] This is confirmed by a recent study showing that the presence of meandering and anabranching rivers, occurrences of large woody debris, and records of log jams decrease significantly at the Moscovian-Kasimovian boundary.[3] Rainforests were fragmented forming shrinking islands further and further apart and in latest Kasimovian time, rainforests vanished from the fossil record.

Animals

Before the collapse, animal species distribution was very cosmopolitan: the same species existed everywhere across tropical Pangaea, but after the collapse each surviving rainforest 'island' developed its own unique mix of species. Many amphibian species became extinct while reptiles diversified into more species after the initial crisis.[1] These patterns are explained by the theory of island biogeography, a concept that explains how evolution progresses when populations are restricted into isolated pockets. This theory was originally developed for oceanic islands but can be applied equally to any other ecosystem that is fragmented, only existing in small patches, surrounded by another habitat. According to this theory, the initial impact of habitat fragmentation is devastating, with most life dying out quickly from lack of resources. Then, as surviving plants and animals reestablish themselves, they adapt to their restricted environment to take advantage of the new allotment of resources and diversify. After the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, each pocket of life evolved in its own way, resulting in a unique species mix which ecologists term endemism.Extinction patterns in the sea

Stanley and Powell (2003) show a small extinction peak for marine fauna in the Moscovian.[6]Biotic recovery and evolutionary consequences

Plants

The fragmentation of wetlands left a few isolated refugia in Europe; however, even these were unable to maintain the diversity of Moscovian flora.[2] By the Asselian many families that characterized the Moscovian tropical wetlands had disappeared including Flemingitaceae, Diaphorodendraceae, Tedeleaceae, Urnatopteridaceae, Alethopteridaceae, Cyclopteridaceae, Neurodontopteridaceae.[2]Invertebrates

The depletion of the plant life contributed to the deteriorating levels of oxygen in the atmosphere, which facilitated the enormous arthropods of the time. Due to the decreasing oxygen, these sizes could no longer be accommodated, and thus between this and the loss of habitat, the giant arthropods were wiped out in this event, most notably the giant dragonflies and millipedes (Meganeura and Arthropleura).Vertebrates

Terrestrially adapted early mammal-like reptiles like Archaeothyris were among the groups who quickly recovered after the collapse.

This sudden collapse affected several large groups. Labyrinthodont amphibians were particularly devastated, while the first reptiles fared better, being ecologically adapted to the drier conditions that followed. Amphibians must return to water to lay eggs; in contrast, reptiles – whose amniote eggs have a membrane ensuring gas exchange out of water and can therefore be laid on land – were better adapted to the new conditions. Reptiles acquired new niches at a faster rate than before the collapse and at a much faster rate than amphibians. They acquired new feeding strategies including herbivory and carnivory, previously only having been insectivores and piscivores.[1]

This extinction event had long term implications for the evolution of amphibians. Under prolonged cold conditions, amphibians can survive by decreasing metabolic rates and resorting to overwintering strategies (i.e. spending most of the year inactive in burrows or under logs). However, this is only a short term strategy and not an effective way of dealing with prolonged unfavourable conditions, especially desiccation. Since amphibians had a limited capacity to adapt to the drier conditions that dominated Permian environments, many amphibian families failed to occupy new ecological niches and went extinct.[7]

Possible causes

Climate and Atmosphere

There are several hypotheses about the nature and cause of the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, some of which include climate change.[8][9][10] Following a late Bashkirian interval of glaciation, high-frequency shifts in seasonality from humid to arid times began.[11]Beginning in the latest Middle Pennsylvanian (late Moscovian) a cycle of aridifictaion began. At the time Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, the climate became cooler and drier, this is reflected in the rock record as the Earth entered into a short, intense ice age. Sea levels dropped by a hundred metres and glacial ice covered most of the southern continent of Gondwana.[12] The cooler, drier climate conditions were not favourable to the growth of rainforests and much of the biodiversity within them. Rainforests shrank into isolated patches, these islands of rainforest were mostly confined to wet valleys further and further apart. Little of the original lycopsid rainforest biome survived this initial climate crisis. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere crashed to one of its all time global lows in the Pennsylvanian and early Permian.[12] [11]

Then a succeeding period of global warming reversed the climatic trend; the remaining rainforests, unable to survive the rapidly changing conditions, were finally wiped out.

As the climate aridified again through the later Paleozoic, the rainforests were eventually replaced by seasonally dry biomes.[13] Though the exact speed and nature of the collapse is not clear, it is thought to have occurred relatively quickly in geologic terms, only a few thousand years at most.

Volcanism

After restoring the center of the Skagerrak-Centered Large Igneous Province (SCLIP) using a new reference frame, it has been shown that the Skagerrak plume rose from the core–mantle boundary (CMB) to its ~300 Ma position.[14] The major eruption interval took place in very narrow time interval, of 297 Ma ± 4 Ma. This rift formation coincides with the Moskovian/Kasimovian boundary and the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse.[15]Multiple causes

In recent years, scientists have put forth the idea that many of Earth's largest extinction events were due to multiple causes that coincided in time. Proponents of this view suggest multiple causes because they either don't see a single cause as sufficient in strength to cause the mass extinctions or believe that a single cause is likely to produce the taxonomic pattern of the extinction. Two of Earth's largest extinction events have been hypothesized to be multi-causal in nature:The cause of the Permo-Triassic extinction is unclear and some authors have indicated that it may be best explained by a "Murder on the Orient Express Scenario" where multiple causes contributed to a devastating impact on life. Possible causes supported by strong evidence include the large scale volcanism at the Siberian Traps, the releases of noxious gases, global warming, and anoxia (oxygen depletion) .[16]

David Archibald and David E. Fastovsky discussed a scenario combining three major causes to the K-T extinction: volcanism, marine regression, and extraterrestrial impact, together wiping out the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago.[17] The specific cause of the CRC is not known, but certainly a multiple cause scenario is a possibility.

Timing and Periodicity

The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC) was an extinction event that occurred ~307 million years ago, at the end of the Moscovian and the beginning of the Kasimovian stages of the Pennsylvanian.[18] In 1984 Raup and Sepkoski identified a ~26 million year periodicity in the fossil record.[19] Many explanations for this pattern have been proposed including the presence of a hypothetical companion star to the sun,[20] [21] oscillations in the galactic plane, or passage through the Milky Way's spiral arms.[22] The existence of a periodic cycle itself was contentious until 2014 when Melott and Bambach analysed two independent data sets with increased resolution, confirming distinct extinction peaks every 27 million years and specifically, the CRC falls within the maxima of the 27 Myr periodicity cycle (±1.26 Myr).[23]Climate and geology

Paleosols define a stratigraphic trend that is interpreted to reflect a period of overall decreased hydromorphy, increased free-drainage and landscape stability, and a shift in the overall regional climate to drier conditions in the Upper Pennsylvanian (Missourian), which are consistent with climate interpretations based on contemporaneous paleo-floral assemblages and geological evidence.[24][25]Fossil sites

Many fossil sites around the world reflect the changing conditions of the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse.

- Hamilton, USA

- Jarrow, UK

- Linton, USA

- Newsham, USA

- Nyrany, Czechoslovakia

- Joggins, Canada