A functional neurological disorder (FND) is a condition in which patients experience neurological symptoms such as weakness, movement disorders, sensory symptoms and blackouts. The brain of a patient with functional neurological symptom disorder is structurally normal, but functions incorrectly.

According to consensus from the literature and from physicians and

psychologists practicing in the field, functional symptoms are also

called 'medically unexplained'. Historically, other terms have been used

to describe these symptoms. Symptoms of functional neurological

disorders are clinically recognisable, but are not categorically

associated with a definable organic disease. The intended contrast is with an organic brain syndrome,

although the terms imply a level of certainty about causation that is

often clinically unconfirmed. Subsets of functional neurological

disorders include functional neurological symptom disorder (FNsD), conversion disorder, and psychogenic movement disorder/non-epileptic seizures.

Functional neurological disorders are common in neurological services,

accounting for up to one third of outpatient neurology clinic

attendances, and associated with as much physical disability and

distress as other neurological disorders.

The diagnosis is made based on positive signs and symptoms in the

history and examination during consultation of a neurologist (see

below). Physiotherapy is particularly helpful for patients with motor

symptoms (weakness, gait disorders, movement disorders) and tailored cognitive behavioural therapy has the best evidence in patients with dissociative (non-epileptic) attacks.

Signs and symptoms

There

are a great number of symptoms experienced by those with a functional

neurological disorder. It is important to note that the symptoms

experienced by those with an FND are very real. At the same time, the

origin of symptoms is complex since it can be associated with physical

injury, severe psychological trauma

(conversion disorder), and idiopathic neurological dysfunction. The

core symptoms are those of motor or sensory function or episodes of

altered awareness:

- Limb weakness or paralysis

- Blackouts (also called dissociative or non-epileptic seizures/attacks) – these may look like epileptic seizures or faints

- Movement disorders including tremors, dystonia (spasms), myoclonus (jerky movements)

- Visual symptoms including loss of vision or double vision

- Speech symptoms including dysphonia (whispering speech), slurred or stuttering speech

- Sensory disturbance including hemisensory syndrome (altered sensation down one side of the body)

Epidemiology and aetiology

Epidemiology

Functional

neurological disorders are a common problem, and are the second most

common reason for a neurological outpatient visit after

headache/migraine. Dissociative (non-epileptic) seizures account for

about 1 in 7 referrals to neurologists after an initial seizure, and

functional weakness has a similar prevalence to multiple sclerosis.

Aetiology and mechanism

Epidemiological

studies and meta-analysis have shown higher rates of depression and

anxiety in patients with FND compared to the general population, but

rates are similar to patients with other neurological disorders such as

epilepsy or Parkinson's disease. This is often the case because of years of misdiagnosis and accusations of malingering.

Diagnostic criteria

A diagnosis of a functional neurological disorder is dependent on positive features from the history and examination.

Positive features of functional weakness on examination include

Hoover’s sign, when there is weakness of hip extension which normalises

with contralateral hip flexion, and thigh abductor sign, weakness of

thigh abduction which normalises with contralateral thigh abduction.

Signs of functional tremor include entrainment and distractibility. The

patient with tremor should be asked to copy rhythmical movements with

one hand or foot. If the tremor of the other hand entrains to the same

rhythm, stops, or if the patient has trouble copying a simple movement

this may indicate a functional tremor. Functional dystonia usually

presents with an inverted ankle posture or clenched fist.

Positive features of dissociative or non-epileptic attacks include

prolonged motionless unresponsiveness, long duration episodes

(>2minutes) and symptoms of dissociation prior to the attack. These

signs can be usefully discussed with patients when the diagnosis is

being made.

Patients with functional movement disorders and limb weakness may

experience symptom onset triggered by an episode of acute pain, a

physical injury or physical trauma. They may also experience symptoms

when faced with a psychological stressor, but this isn't the case for

most patients. Patients with functional neurological disorders are more

likely to have a history of another illness such as irritable bowel

syndrome, chronic pelvic pain or fibromyalgia but this cannot be used to

make a diagnosis.

FND does not show up on blood tests or structural brain imaging such as

MRI or CT scanning. However, this is also the case for many other

neurological conditions so negative investigations should not be used

alone to make the diagnosis. FND can, however, occur alongside other

neurological diseases and tests may show non-specific abnormalities

which cause confusion for doctors and patients.

ICD-11 diagnostic criteria

The

International Classification of Disease (ICD-11) which is due to be

finalised in 2017 will have functional disorders within the neurology

section for the first time.

Prevalence

Functional

neurological disorder is a common problem, with estimates suggesting

that up to a third of neurology outpatients having functional symptoms. In Scotland, around 5000 new cases of FND are diagnosed annually.

Furthermore, non-epileptic seizures account for 1 in 7 referrals to

neurologists after an initial seizure, and functional weakness has a

similar prevalence to multiple sclerosis.

Misdiagnosis

Historically, misdiagnosis rates have been low.

Treatment

Treatment

requires a firm and transparent diagnosis based on positive features

which both health professionals and patients can feel confident about.

It is essential that the health professional confirms that this is a

common problem which is genuine, not imagined and not a diagnosis of

exclusion.

Confidence in the diagnosis does not improve symptoms, but

appears to improve the efficacy of treatments such as physiotherapy

which require altering established abnormal patterns of movement.

A multi-disciplinary approach to treating functional neurological disorder is recommended.

Treatment options can include:

- Physiotherapy and occupational therapy

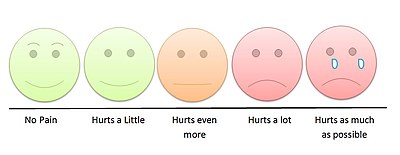

- Medication such as sleeping tablets, painkillers, anti-epileptic medications and anti-depressants (for patients suffering with depression co-morbid or for pain relief)

Physiotherapy with someone who understands functional disorders may

be the initial treatment of choice for patients with motor symptoms such

as weakness, gait (walking) disorder and movement disorders. Nielsen

et al. have reviewed the medical literature on physiotherapy for

functional motor disorders up to 2012 and concluded that the available

studies, although limited, mainly report positive results.

Since then several studies have shown positive outcomes. In one study,

up to 65% of patients were very much or much improved after five days of

intensive physiotherapy even though 55% of patients were thought to

have poor prognosis.

In a randomised controlled trial of physiotherapy there was significant

improvement in mobility which was sustained on one year follow up.

In multidisciplinary settings 69% of patients markedly improved even

with short rehabilitation programmes. Benefit from treatment continued

even when patients were contacted up 25 months after treatment.

For patients with severe and chronic FND a combination of

physiotherapy, occupational therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy

may be the best combination with positive studies being published in

patients who have had symptoms for up to three years before treatment.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) alone may be beneficial in

treating patients with dissociative (non-epileptic) seizures. A

randomised controlled trial of patients who undertook 12 sessions of CBT

which taught patients how to interrupt warning signs before seizure

onset, challenged unhelpful thoughts and helped patients start

activities they had been avoiding found a reduction in the seizure

frequency with positive outcomes sustained at six month follow up. A

large multicentre trial of CBT for dissociative (non-epileptic) seizures

started in 2015 in the UK.

For many patients with FND, accessing treatment can be difficult.

Availability of expertise is limited and they may feel that they are

being dismissed or told 'it's all in your head' especially if

psychological input is part of the treatment plan. Some medical

professionals are uncomfortable explaining and treating patients with

functional symptoms. Changes in the diagnostic criteria, increasing

evidence, literature about how to make the diagnosis and how to explain

it and changes in medical training is slowly changing this.

After a diagnosis of functional neurological disorder has been

made, it is important that the neurologist explains the illness fully to

the patient to ensure the patient understands the diagnosis.

Some, but not all patients with FND may experience low moods or

anxiety due to their condition. However, they will often not seek

treatment due being worried that a doctor will blame their symptoms on

their anxiety or depression.

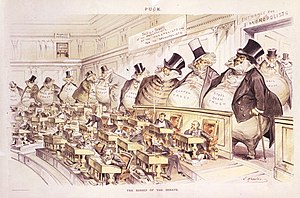

It is recommended that the treatment of functional neurological

disorder should be balanced and involve a whole-person approach. This

means that it should include professionals from multiple departments,

including neurologists, general practitioners (or primary health care

providers), physiotherapists, occupational therapists. At the same time,

ruling out secondary gain, malingering, conversion disorder and other

factors, including the time and financial resources involved in

assessing and treating patients who demand hospital resources but would

be better served in psychological settings, must all be balanced.

Alternative diagnoses

Functional neurological symptom disorder can very rarely mimic many other conditions. Some alternative diagnoses for FND that are often considered include:

- Hemiplegic migraine

- Multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson's

- Autoimmune disorders

- Stroke

- Vitamin B12 deficiency or pernicious anaemia

- Myasthenia gravis

The main caveat however is that these conditions can co-exist and can be the trigger for functional neurological disorder.

History

From

the 18th century, there is a move from the idea of FND being caused

being caused by the nervous system. This led to an understanding that it

could affect both sexes. Jean Martin Charcot argued that, what would be

later called FND, was caused by "a hereditary degeneration of the

nervous system, namely a neurological disorder".

In the 18th century, the illness was confirmed as being a

neurological disorder but a small number of doctors still believed in

the previous definition.

However, as early as 1874, doctors including W. B. Carpenter and J. A.

Omerod began to speak out against this other term due to there being no

evidence of its existence.

Although the term "conversion disorder" has been in existence for

many years, another term was still being used in the 20th century.

However, by this point, it bore little resemblance to the original

meaning, instead referring to symptoms which could not be explained by a

recognised organic pathology, and was therefore believed to be the

result of stress, anxiety, trauma or depression. The term fell out of

favour of doctors over time due to the negative connotations this term

held. Furthermore, critics pointed out that it can be challenging to

find organic pathologies for all symptoms, and so the practice of

diagnosing patients who suffered with such symptoms as imagining them

led to the disorder being meaningless, vague and a sham-diagnosis, as it

does not refer to any definable disease.

Throughout its history, many patients have been misdiagnosed with

conversion disorder when they had organic disorders such as tumours or

epilepsy or vascular diseases. This has led to patient deaths, a lack of

appropriate care and suffering for the patients. Eliot Slater, after

studying the condition in the 1950s, was outspoken against the

condition, as there has never been any evidence to prove that it exists.

He stated that "The diagnosis of 'hysteria' is a disguise for ignorance

and a fertile source of clinical error. It is, in fact, not only a

delusion but also a snare".

In 1980, the DSM III added 'conversion disorder' to its list of

conditions. The diagnostic criteria for this condition are nearly

identical to those used for hysteria. The diagnostic criteria were:

B. One of the following must also be present:

- A temporal relationship between symptom onset and some external event of psychological conflict.

- The symptom allows the individual to avoid unpleasant activity.

- The symptom provides opportunity for support which may not have been otherwise available.

Many illnesses and injuries can cause an individual to avoid

unpleasant activities, and can provide the opportunity for support,

particularly from a doctor. This makes Criteria B meaningless for the

most part, and therefore any patient whose symptoms satisfy Criteria A

by being medically unexplained, could be diagnosed with Conversion

Disorder.

Today, there is growing evidence that psychological stress does

not cause FND. A recent study by the charity FNDHope found that

psychological triggers affected only 30% of patients. Doctors are moving

on to look at the role of the central nervous system in FND symptoms.

Controversy

There

was historically much controversy surrounding the FND diagnosis. Many

doctors continue to believe that all FND patients have unresolved

traumatic events (often of a sexual nature) which are being expressed in

a physical way. However, some doctors do not believe this to be the

case. Wessely and White have argued that FND may merely be an

unexplained somatic illness (like fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, or chronic fatigue syndrome) rather than a psychiatric condition.