Milford Sound, New Zealand is a strict marine reserve (Category Ia) Mitre Peak, the mountain at left, rises 1,692 m (5,551 ft) above the sea.

Marine protected areas (MPA) are protected areas of seas, oceans, estuaries or in the US, the Great Lakes . These marine areas can come in many forms ranging from wildlife refuges to research facilities. MPAs restrict human activity for a conservation purpose, typically to protect natural or cultural resources.

Such marine resources are protected by local, state, territorial,

native, regional, national, or international authorities and differ

substantially among and between nations. This variation includes

different limitations on development, fishing practices, fishing seasons

and catch limits, moorings and bans on removing or disrupting marine

life. In some situations (such as with the Phoenix Islands Protected Area),

MPAs also provide revenue for countries, potentially equal to the

income that they would have if they were to grant companies permissions

to fish.

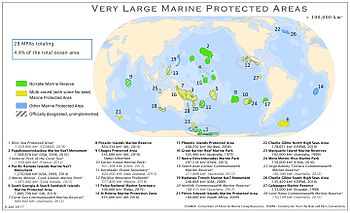

On 28 October 2016 in Hobart, Australia, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources agreed to establish the first Antarctic and largest marine protected area in the world encompassing 1.55 million km2 (600,000 sq mi) in the Ross Sea. Other large MPAs are in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans, in certain exclusive economic zones of Australia and overseas territories of France, the United Kingdom and the United States, with major (990,000 square kilometres (380,000 sq mi) or larger) new or expanded MPAs by these nations since 2012—such as Natural Park of the Coral Sea, Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, Coral Sea Commonwealth Marine Reserve and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Marine Protected Area.

When counted with MPAs of all sizes from many other countries, as of

August 2016 there are more than 13,650 MPAs, encompassing 2.07% of the

world's oceans, with half of that area – encompassing 1.03% of the

world's oceans – receiving complete "no-take" designation.

Terminology

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as:

"A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values."

This definition is intended to make it more difficult to claim MPA

status for regions where exploitation of marine resources occurs. If

there is no defined long-term goal for conservation and ecological

recovery and extraction of marine resources occurs, a region is not a

marine protected area.

"Marine protected area (MPA)" is a term for protected areas that include marine environment and biodiversity.

Other definitions by the IUCN include (2010):

"Any area of the intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment."

United States Executive Order 13158 in May 2000 established MPAs, defining them as;

"Any area of the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, tribal, territorial, or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for part or all of the natural and cultural resources therein."

The Convention on Biological Diversity defined the broader term of marine and coastal protected area (MCPA);

"Any defined area within or adjacent to the marine environment, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by legislation or other effective means, including custom, with the effect that its marine and/or coastal biodiversity enjoys a higher level of protection than its surroundings."

An apparently unique extension of the meaning is used by NOAA to refer to protected areas on the Great Lakes of North America.

Classifications

The Chagos Archipelago

was declared the world's largest marine reserve in April 2010 with an

area of 250,000 square miles until March 2015 when It was declared

illegal by the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Several types of compliant MPA can be distinguished:

- A totally marine area with no significant terrestrial parts.

- An area containing both marine and terrestrial components, which can vary between two extremes; those that are predominantly maritime with little land (for example, an atoll would have a tiny island with a significant maritime population surrounding it), or that is mostly terrestrial.

- Marine ecosystems that contain land and intertidal components only. For example, a mangrove forest would contain no open sea or ocean marine environment, but its river-like marine ecosystem nevertheless complies with the definition.

IUCN offered seven categories of protected area, based on management objectives and four broad governance types.

| Cat | IUCN Protected Area Management Categories: |

|---|

| Strict nature reserve A marine reserve usually connotes "maximum protection", where all resource removals are strictly prohibited. In countries such as Kenya and Belize, marine reserves allow for low-risk removals to sustain local communities. | |

| Wilderness area | |

| National park Marine parks emphasize the protection of ecosystems but allow light human use. A marine park may prohibit fishing or extraction of resources, but allow recreation. Some marine parks, such as those in Tanzania, are zoned and allow activities such as fishing only in low risk areas. | |

| Natural monuments or features Established to protect historical sites such as shipwrecks and cultural sites such as aboriginal fishing grounds. | |

| Habitat/species management area Established to protect a certain species, to benefit fisheries, rare habitat, as spawning/nursing grounds for fish, or to protect entire ecosystems. | |

| Protected seascape Limited active management, as with protected landscapes. | |

| Sustainable use of natural resources |

Related protected area categories include the following;

- World Heritage Site (WHS) – an area exhibiting extensive natural or cultural history. Maritime areas are poorly represented, however, with only 46 out of over 800 sites.

- Man and the Biosphere – UNESCO program that promotes "a balanced relationship between humans and the biosphere". Under article 4, biosphere reserves must "encompass a mosaic of ecological systems", and thus combine terrestrial, coastal, or marine ecosystems. In structure they are similar to Multiple-use MPAs, with a core area ringed by different degrees of protection.

- Ramsar site – must meet certain criteria for the definition of "Wetland" to become part of a global system. These sites do not necessarily receive protection, but are indexed by importance for later recommendation to an agency that could designate it a protected area.

While "area" refers to a single contiguous location, terms such as "network", "system", and "region" that group MPAs are not always consistently employed."System" is more often used to refer to an individual MPA, whereas "region" is defined by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre as:

"A collection of individual MPAs operating cooperatively, at various spatial scales and with a range of protection levels that are designed to meet objectives that a single reserve cannot achieve."

At the 2004 Convention on Biological Diversity, the agency agreed to use "network" on a global level, while adopting system for national and regional levels. The network is a mechanism to establish regional and local systems, but carries no authority or mandate, leaving all activity within the "system".

No take zones (NTZs), are areas designated in a number of

the world's MPAs, where all forms of exploitation are prohibited and

severely limits human activities. These no take zones can cover an

entire MPA, or specific portions. For example, the 1,150,000 square

kilometres (440,000 sq mi) Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, the world's largest MPA (and largest protected area of any type, land or sea), is a 100% no take zone.

Related terms include; specially protected area (SPA), Special Area of Conservation (SAC), the United Kingdom's marine conservation zones (MCZs), or area of special conservation (ASC) etc. which each provide specific restrictions.

Stressors

Stressors that affect oceans include "the impact of extractive industries, localised pollution, and changes to its chemistry (ocean acidification) resulting from elevated carbon dioxide levels, due to our emissions".

MPAs have been cited as the ocean's single greatest hope for increasing

the resilience of the marine environment to such stressors.

Well-designed and managed MPAs developed with input and support from

interested stakeholders can conserve biodiversity and protect and

restore fisheries.

Economics

MPAs can help sustain local economies by supporting fisheries and tourism. For example, Apo Island in the Philippines made protected one quarter of their reef, allowing fish to recover, jumpstarting their economy. This was shown in the film, Resources at Risk: Philippine Coral Reef. A 2016 report by the Center for Development and Strategy found that programs like the United States National Marine Sanctuary system can develop considerable economic benefits for communities through Public–private partnerships.

Management

Typical MPAs restrict fishing, oil and gas mining and/or tourism. Other restrictions may limit the use of ultrasonic devices like sonar (which may confuse the guidance system of cetaceans),

development, construction and the like. Some fishing restrictions

include "no-take" zones, which means that no fishing is allowed. Less

than 1% of US MPAs are no-take.

Ship transit can also be restricted or banned, either as a

preventive measure or to avoid direct disturbance to individual species.

The degree to which environmental regulations affect shipping varies

according to whether MPAs are located in territorial waters, exclusive economic zones, or the high seas. The law of the sea regulates these limits.

Most MPAs have been located in territorial waters, where the

appropriate government can enforce them. However, MPAs have been

established in exclusive economic zones and in international waters. For example, Italy, France and Monaco in 1999 jointly established a cetacean sanctuary in the Ligurian Sea named the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals. This sanctuary includes both national and international waters. Both the CBD and IUCN

recommended a variety of management systems for use in a protected area

system. They advocated that MPAs be seen as one of many "nodes" in a

network of protected areas. The following are the most common management systems.

Asinara,

Italy is listed by WDPA as both a marine reserve and a national marine

park, and as such could be labelled 'multiple-use'

Seasonal and temporary management—Activities, most critically

fishing, are restricted seasonally or temporarily, e.g., to protect

spawning/nursing grounds or to let a rapidly reducing species recover.

Multiple-use MPAs—These are the most common and arguably

the most effective. These areas employ two or more protections. The most

important sections get the highest protection, such as a no take zone

and are surrounded with areas of lesser protections.

Community involvement and related approaches—Community-managed

MPAs empower local communities to operate partially or completely

independent of the governmental jurisdictions they occupy. Empowering

communities to manage resources can lower conflict levels and enlist the

support of diverse groups that rely on the resource such as subsistence

and commercial fishers, scientists, recreation, tourism businesses,

youths and others.

Marine Protected Area Networks

Marine Protected Area Networks or MPA networks have been defined as "A group of MPAs that interact with one another ecologically and/or socially form a network".

These networks are intended to connect individuals and MPAs and

promote education and cooperation among various administrations and user

groups. "MPA networks are, from the perspective of resource users,

intended to address both environmental and socio-economic needs,

complementary ecological and social goals and designs need greater

research and policy support".

Filipino communities connect with one another to share

information about MPAs, creating a larger network through the social

communities' support. Emerging or established MPA networks can be found in Australia, Belize, the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Mexico.

International efforts

The 17th International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) General Assembly in San Jose,

California, the 19th IUCN assembly and the fourth World Parks Congress

all proposed to centralise the establishment of protected areas. The World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 called for

the establishment of marine protected areas consistent with international laws and based on scientific information, including representative networks by 2012.

The Evian agreement, signed by G8 Nations

in 2003, agreed to these terms. The Durban Action Plan, developed in

2003, called for regional action and targets to establish a network of

protected areas by 2010 within the jurisdiction of regional environmental protocols.It recommended establishing protected areas for 20 to 30% of the world's oceans by the goal date of 2012. The Convention on Biological Diversity

considered these recommendations and recommended requiring countries to

set up marine parks controlled by a central organization before merging

them. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed to the terms laid out by the convention, and in 2004, its member nations committed to the following targets;

- By 2006 complete an area system gap analysis at national and regional levels.

- By 2008 address the less represented marine ecosystems, accounting for those beyond national jurisdiction in accordance.

- By 2009 designate the protected areas identified through the gap analysis.

- By 2012 complete the establishment of a comprehensive and ecologically representative network.

Bunaken Marine Park, Indonesia is officially listed as both a marine reserve and a national marine park.

"The establishment by 2010 of terrestrial and by 2012 for marine areas of comprehensive, effectively managed, and ecologically representative national and regional systems of protected areas that collectively, inter alia through a global network, contribute to achieving the three objectives of the Convention and the 2010 target to significantly reduce the current late of biodiversity loss at the global, regional, national, and sub-national levels and contribute to poverty reduction and the pursuit of sustainable development."

The UN later endorsed another decision, Decision VII/15, in 2006:

Effective conservation of 10% of each of the world's ecological regions by 2010.

– United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Decision VII/15

The 10% conservation goal is also found in Sustainable Development Goal 14 (which is part of the Convention on Biological Diversity) and which sets this 10% goal to a later date (2020). In 2017, the UN held the United Nations Ocean Conference

aiming to find ways and urge for the implementation of Sustainable

Development Goal 14. I that 2017 conference, it was clear that just

between 3,6 to 5,7% of the world's oceans were protected, meaning

another 6,4 to 4,3% of the world's oceans needed to be protected within 3

years. The 10% protection goal is described as a "baby step" as 30% is the real

amount of ocean protection scientists agree on that should be

implemented.

Global treaties

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The Antarctic Treaty System

On

7 April 1982, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine

Living Resources (CAMLR Convention) came into force after discussions

began in 1975 between parties of the then-current Antarctic Treaty to limit large-scale exploitation of krill

by commercial fisheries. The Convention bound contracting nations to

abide by previously agreed upon Antarctic territorial claims and

peaceful use of the region while protecting ecosystem integrity south of

the Antarctic Convergence and 60 S latitude.

In so doing, it also established a commission of the original

signatories and acceding parties called the Commission for the

Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) to advance

these aims through protection, scientific study, and rational use, such

as harvesting, of those marine resources. Though separate, the Antarctic

Treaty and CCAMLR, make up part the broader system of international

agreements called the Antarctic Treaty System. Since 1982, the CCAMLR

meets annually to implement binding conservations measures like the

creation of 'protected areas' at the suggestion of the convention's

scientific committee.

In 2009, the CCAMLR created the first 'high-seas' MPA entirely within international waters over the southern shelf of the South Orkney Islands.

This area encompasses 94,000 square kilometres (36,000 sq mi) and all

fishing activity including transhipment, and dumping or discharge of

waste is prohibited with the exception of scientific research endeavors.

On 28 October 2016, the CCAMLR, composed of 24 member countries and the

European Union at the time, agreed to establish the world's largest

marine park encompassing 1.55 million km2 (600,000 sq mi) in

the Ross Sea after several years of failed negotiations. Establishment

of the Ross Sea MPA required unanimity of the commission members and

enforcement will begin in December 2017. However, due to a sunset

provision inserted into the proposal, the new marine park will only be

in force for 35 years.

Regional Organizations

PIMPAC

Pacific Islands Marine Protected Areas Community

NAMPAN

North American Marine Protected Areas Network

CCAMLR

Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

National Targets

Many

countries have established national targets, accompanied by action

plans and implementations. The UN Council identified the need for

countries to collaborate with each other to establish effective regional

conservation plans. Some national targets are listed in the table below.

| Country | Plan of action |

|---|---|

| American Samoa | 20% of reefs to be protected by 2010 |

| Australia – South Australia | 19 marine protected areas by 2010 |

| Bahamas | 20% of the marine ecosystem protected for fishery replenishment by 2010. 20% of coastal and marine habitats by 2015. |

| Belize | 20% of bioregions.

30% of Coral reefs.

60% of turtle nesting sites. 30% of Manatee distribution. 60% of American crocodile nesting. 80% of breeding areas. |

| Chile | 10% of marine areas by 2010. National network for organization by 2015. |

| Cuba | 22% of land habitat, including:

|

| Dominican Republic | 20% of marine and coastal by 2020. |

| Micronesia | 30% of shoreline ecosystems by 2020. |

| Fiji | 30% of reefs by 2015.

30% of water managed by marine protected areas by 2020.

|

| Germany | 38% of water managed by the marine protected network. (no set date) |

| Grenada | 25% of nearby marine resources by 2020. |

| Guam | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Indonesia | 100,000 km2 by 2010.

200,000 km2 by 2020.

|

| Republic of Ireland | 14% of territorial waters as of 2009[38] |

| Isle of Man | 10% of Manx waters as 'effectively managed, ecologically representative and well-connected protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures' by 2020. As of June 2016, approximately 3% of Manx waters were protected as a Marine Nature Reserve, with additional areas subject to seasonal or temporary protection.[39] |

| Jamaica | 20% of marine habitats by 2020. |

| Madagascar | 100,000 km2 by 2012. |

| Marshal Islands | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| New Zealand | 20% of marine environment by 2010. |

| North Mariana Islands | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Palau | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Peru | Marine protected area system established by 2015. |

| Philippines | 10% fully protected by 2020. |

| Senegal | Creation of MPA network. (no set date) |

| South Africa | 10% of exclusive economic zone by 2020 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 20% of marine areas by 2020. |

| Tanzania | 10% of marine area by 2010; 20% by 2020. |

| United Kingdom | Establish an ecologically coherent network of marine protected areas by 2012. |

| United States – California | 29 MPAs covering 18% of state marine area with 243 square kilometres (94 sq mi) at maximum protection. |

The prevalent practice of area-based targets was criticized in 2019

by a group of environmental scientists because politicians tended to

protect parts of the oceans where little fishing happened to meet the

goals. The lack of fishing in these areas made them easy to protect, but

it also had little positive impact.

National efforts

The

marine protected area network is still in its infancy. As of October

2010, approximately 6,800 MPAs had been established, covering 1.17% of

global ocean area. Protected areas covered 2.86% of exclusive economic

zones (EEZs). MPAs covered 6.3% of territorial seas. Many prohibit the use of harmful fishing techniques yet only 0.01% of the ocean's area is designated as a "no take zone". This coverage is far below the projected goal of 20%-30%

Those targets have been questioned mainly due to the cost of managing

protected areas and the conflict that protections have generated with

human demand for marine goods and services.

Africa

South Africa

A marine protected area of South Africa is an area of coastline or ocean within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the Republic of South Africa that is protected in terms of specific legislation.

There are a total of 45 marine protected areas

in the South African EEZ, with a total area of 5% of the waters. The

target is to have 10% of the oceanic waters protected by 2020. All but

one of the MPAs are in the coastal waters off continental South Africa,

and one is off Prince Edward Island in the Southern Ocean.

Greater Caribbean

The Caribbean region; the UNEP–defined region also includes the Gulf of Mexico. This region is encompassed by the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System proposal, and the Caribbean challenge

The Gulf of Mexico region (in 3D) is encompassed by the "Islands in the Stream" proposal.

The Greater Caribbean

subdivision encompasses an area of about 5,700,000 square kilometres

(2,200,000 sq mi) of ocean and 38 nations. The area includes island

countries like the Bahamas and Cuba, and the majority of Central America. The Convention for Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region (better known as the Cartagena Convention) was established in 1983. Protocols involving protected areas were ratified in 1990. As of 2008, the region hosted about 500 MPAs. Coral reefs are the best represented.

Two networks are under development, the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (a long barrier reef that borders the coast of much of Central America), and the "Islands in the Stream" program (covering the Gulf of Mexico).

Southeast Asia

Southeast

Asia is a global epicenter for marine diversity. 12% of its coral reefs

are in MPAs. The Philippines have some the world's best coral reefs and

protect them to attract international tourism. Most of the Philippines'

MPAs are established to secure protection for its coral reef and sea grass habitats. Indonesia has MPAs designed for tourism and relies on tourism as a main source of income.

Philippines

The Philippines

host one of the most highly biodiverse regions, with 464 reef-building

coral species. Due to overfishing, destructive fishing techniques, and

rapid coastal development, these are in rapid decline. The country has

established some 600 MPAs. However, the majority are poorly enforced and

are highly ineffective. However, some have positively impacted reef

health, increased fish biomass, decreased coral bleaching and increased

yields in adjacent fisheries. One notable example is the MPA surrounding

Apo Island.

Latin America

Latin America

has designated one large MPA system. As of 2008, 0.5% of its marine

environment was protected, mostly through the use of small, multiple-use

MPAs.

South Pacific

The South Pacific network ranges from Belize to Chile. Governments in the region adopted the Lima convention

and action plan in 1981. An MPA-specific protocol was ratified in 1989.

The permanent commission on the exploitation and conservation on the

marine resources of the South Pacific promotes the exchange of studies

and information among participants.

The region is currently running one comprehensive cross-national

program, the Tropical Eastern Pacific Marine Corridor Network, signed in

April 2004. The network covers about 211,000,000 square kilometres

(81,000,000 sq mi).

One alternative to imposing MPAs on an indigenous population is through the use of Indigenous Protected Areas, such as those in Australia.

North Pacific

The

North Pacific network covers the western coasts of Mexico, Canada, and

the U.S. The "Antigua Convention" and an action plan for the north

Pacific region were adapted in 2002. Participant nations manage their

own national systems.

In 2010-2011, the State of California completed hearings and actions

via the state Department of Fish and Game to establish new MPAs.

United States and Pacific Island Territories

President Barack Obama

signed a proclamation on September 25, 2014, designating the world's

largest marine reserve. The proclamation expanded the existing Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument,

one of the world's most pristine tropical marine environments, to six

times its current size, encompassing 490,000 square miles (1,300,000 km2) of protected area around these islands. Expanding the Monument protected the area's unique deep coral reefs and seamounts.

Diagram illustrating the orientation of the 3 marine sanctuaries of Central California: Cordell Bank, Gulf of the Farallones, and Monterey Bay. Davidson Seamount, part of the Monterey Bay sanctuary, is indicated at bottom-right.

In April 2009, the US established a United States National System of Marine Protected Areas, which strengthens the protection of US ocean, coastal and Great Lakes resources. These large-scale MPAs should balance "the interests of conservationists, fishers, and the public."

As of 2009, 225 MPAs participated in the national system. Sites work

together toward common national and regional conservation goals and

priorities. NOAA's national marine protected areas center maintains a

comprehensive inventory

of all 1,600+ MPAs within the US exclusive economic zone. Most US

MPAs.allow some type of extractive use. Fewer than 1% of U.S. waters

prohibit all extractive activities.

In 1981 Olympic National Park became a marine protected area. The total protected site area is 3,697 square kilometres (1,427 sq mi). 173.2 km2 of the area was an MPA. The national system is a mechanism to foster MPA collaboration. Sites that meet pertinent criteria are eligible to join the national system. Four entry criteria govern admission:

- Meets the definition of an MPA as defined in the Framework.

- Has a management plan (can be sitespecific or part of a broader programmatic management plan; must have goals and objectives and call for monitoring or evaluation of those goals and objectives).

- Contributes to at least one priority conservation objective as listed in the Framework.

- Cultural heritage MPAs must also conform to criteria for the National Register for Historic Places."

In 1999, California adopted the Marine Life Protection Act, establishing the first state law requiring a comprehensive, science-based MPA network. The state created the Marine Life Protection Act Initiative.

The MLPA Blue Ribbon Task Force and stakeholder and scientific advisory

groups ensure that the process uses the science and public

participation.

The MLPA Initiative established a plan to create California's

statewide MPA network by 2011 in several steps. The Central Coast step

was successfully completed in September, 2007. The North Central Coast

step was completed in 2010. The South Coast and North Coast steps were

expected to go into effect in 2012.

Indian Ocean

In exchange for some of its national debt being written off, the Seychelles designates two new marine protected areas in the Indian Ocean, covering about 210,000 square kilometres (81,000 sq mi). It is the result of a financial deal, brokered in 2016 by The Nature Conservancy.

United Kingdom and British Overseas Territories

United Kingdom

There are a number of marine protected areas around the coastline of the United Kingdom, known as Marine Conservation Zones in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and Marine Protected Areas in Scotland. They are to be found in inshore and offshore waters.

British Overseas Territories

The United Kingdom is also creating marine protected reserves around several British Overseas Territories.

The UK is responsible for 6.8 million square kilometres of ocean around the world, larger than all but four other countries.

The Chagos Marine Protected Area

in the Indian Ocean was established in 2010 as a "no-take-zone". With a

total surface area of 640,000 square kilometres (250,000 sq mi), it

was the world's largest contiguous marine reserve. In March 2015, the UK announced the creation of a marine reserve around the Pitcairn Islands

in the Southern Pacific Ocean to protect its special biodiversity. The

area of 830,000 square kilometres (320,000 sq mi) surpassed the Chagos

Marine Protected Area as the world's largest contiguous marine reserve, until the August 2016 expansion of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the United States to 1,510,000 square kilometres (580,000 sq mi).

In January 2016, the UK government announced the intention to create a marine protected area around Ascension Island. The protected area will be 234,291 square kilometres (90,460 sq mi), half of which will be closed to fishing.

Europe

The Natura 2000 ecological MPA network in the European Union included MPAs in the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea and the Baltic Sea. The member states had to define NATURA 2000 areas at sea in their Exclusive Economic Zone.

Two assessments, conducted thirty years apart, of three

Mediterranean MPAs, demonstrate that proper protection allows

commercially valuable and slow-growing red coral (Corallium rubrum)

to produce large colonies in shallow water of less than 50 metres

(160 ft). Shallow-water colonies outside these decades-old MPAs are

typically very small. The MPAs are Banyuls, Carry-le-Rouet and Scandola, off the island of Corsica.

- Mediterranean Science Commission; proposed the creation of 7 marine protected areas ("peace parcs")

- WWF together with other partners proposed the creation of MedPan (Network of Marine Protected Areas Managers in the Mediterranean) which aims to protect 10% of the surface of the mediterranean by 2020

Notable marine protected areas

Marine protected areas

- The Bowie Seamount Marine Protected Area off the coast of British Columbia, Canada.

- The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Queensland, Australia.

- The Ligurian Sea Cetacean Sanctuary in the seas of Italy, Monaco and France.

- The Dry Tortugas National Park in the Florida Keys, USA.

- The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii.

- The Phoenix Islands Protected Area, Kiribati.

- The Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary in California, USA.

- The Chagos Marine Protected Area in the Indian Ocean.

- The Wadden Sea bordering the North Sea in the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark.

Assessment

The Prickly Pear Cays are a marine protected area, roughly six miles from Road Bay, Anguilla, in the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean.

Managers and scientists use geographic information systems and remote sensing

to map and analyze MPAs. NOAA Coastal Services Center compiled an

"Inventory of GIS-Based Decision-Support Tools for MPAs." The report

focuses on GIS tools with the highest utility for MPA processes. Remote sensing uses advances in aerial photography image capture, pop-up archival satellite tags, satellite imagery, acoustic data, and radar imagery.

Mathematical models that seek to reflect the complexity of the natural

setting may assist in planning harvesting strategies and sustaining

fishing grounds.

Coral reefs

Coral reef systems have been in decline worldwide. Causes include overfishing, pollution and ocean acidification. As of 2013 30% of the world's reefs were severely damaged. Approximately 60% will be lost by 2030 without enhanced protection. Marine reserves with "no take zones" are the most effective form of protection. Only about 0.01% of the world's coral reefs are inside effective MPAs.

Fish

MPAs can be an effective tool to maintain fish populations.

The general concept is to create overpopulation within the MPA. The

fish expand into the surrounding areas to reduce crowding, increasing

the population of unprotected areas.

This helps support local fisheries in the surrounding area, while

maintaining a healthy population within the MPA. Such MPAs are most

commonly used for coral reef ecosystems.

One example is at Goat Island Bay in New Zealand, established in

1977. Research gathered at Goat Bay documented the spillover effect.

"Spillover and larval export—the drifting of millions of eggs and larvae

beyond the reserve—have become central concepts of marine

conservation". This positively impacted commercial fishermen in

surrounding areas.

Another unexpected result of MPAs is their impact on predatory

marine species, which in some conditions can increase in population.

When this occurs, prey populations decrease. One study showed that in 21

out of 39 cases, "trophic cascades," caused a decrease in herbivores,

which led to an increase in the quantity of plant life. (This occurred

in the Malindi Kisite and Watamu Marian National Parks in Kenya; the

Leigh Marine Reserve in New Zealand; and Brackett's Landing Conservation

Area in the US.

Success criteria

Both CBD and IUCN have criteria for setting up and maintaining MPA networks, which emphasize 4 factors:

- Adequacy—ensuring that the sites have the size, shape, and distribution to ensure the success of selected species.

- Representability—protection for all of the local environment's biological processes

- Resilience—the resistance of the system to natural disaster, such as a tsunami or flood.

- Connectivity—maintaining population links across nearby MPAs.

Misconceptions

Misconceptions

about MPAs include the belief that all MPAs are no-take or no-fishing

areas. However, less than 1 percent of US waters are no-take areas. MPA

activities can include consumption fishing, diving and other activities.

Another misconception is that most MPAs are federally managed.

Instead, MPAs are managed under hundreds of laws and jurisdictions. They

can exist in state, commonwealth, territory and tribal waters.

Another misconception is that a federal mandate dedicates a set

percentage of ocean to MPAs. Instead the mandate requires an evaluation

of current MPAs and creates a public resource on current MPAs.

Criticism

Some

existing and proposed MPAs have been criticized by indigenous

populations and their supporters, as impinging on land usage rights. For

example, the proposed Chagos Protected Area in the Chagos Islands is

contested by Chagossians deported from their homeland in 1965 by the British as part of the creation of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). According to WikiLeaks CableGate documents,

the UK proposed that the BIOT become a "marine reserve" with the aim of

preventing the former inhabitants from returning to their lands and to

protect the joint UK/US military base on Diego Garcia Island.

Other critiques include: their cost (higher than that of passive

management), conflicts with human development goals, inadequate scope to

address factors such as climate change and invasive species.

Recent research

The larvae of the yellow tang can drift more than 100 miles and reseed in a distant location.

In 2010, one study found that fish larvae can drift on ocean currents and reseed fish stocks

at a distant location. This finding demonstrated that fish populations

can be connected to distant locations through the process of larval

drift.

They investigated the yellow tang, because larva of this species stay in the general area of the reef in which they first settle. The tropical yellow tang is heavily fished by the aquarium

trade. By the late 1990s, their stocks were collapsing. Nine MPAs were

established off the coast of Hawaii to protect them. Larval drift has

helped them establish themselves in different locations, and the fishery

is recovering.

"We've clearly shown that fish larvae that were spawned inside marine

reserves can drift with currents and replenish fished areas long

distances away," said coauthor Mark Hixon.