From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remnants of the Farallon Plate, deep in Earth's mantle. It is thought that much of the plate initially went under North America (particularly the western United States and southwest Canada) at a very shallow angle, creating much of the mountainous terrain in the area (particularly the southern Rocky Mountains).

Plate tectonics (from the Late Latin tectonicus, from the Greek: τεκτονικός "pertaining to building")[1] is a scientific theory that describes the large-scale motion of Earth's lithosphere. This theoretical model builds on the concept of continental drift which was developed during the first few decades of the 20th century. The geoscientific community accepted plate-tectonic theory after seafloor spreading was validated in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

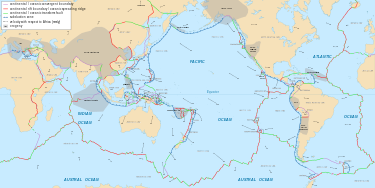

The lithosphere, which is the rigid outermost shell of a planet (the crust and upper mantle), is broken up into tectonic plates. The Earth's lithosphere is composed of seven or eight major plates (depending on how they are defined) and many minor plates. Where the plates meet, their relative motion determines the type of boundary: convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative movement of the plates typically ranges from zero to 100 mm annually.[2]

Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This prediction of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some supporters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or gradual expansion of the globe.[3]

Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth's lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topography and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative importance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate.

Key principles

The outer layers of the Earth are divided into the lithosphere and asthenosphere. This is based on differences in mechanical properties and in the method for the transfer of heat. Mechanically, the lithosphere is cooler and more rigid, while the asthenosphere is hotter and flows more easily. In terms of heat transfer, the lithosphere loses heat by conduction, whereas the asthenosphere also transfers heat by convection and has a nearly adiabatic temperature gradient. This division should not be confused with the chemical subdivision of these same layers into the mantle (comprising both the asthenosphere and the mantle portion of the lithosphere) and the crust: a given piece of mantle may be part of the lithosphere or the asthenosphere at different times depending on its temperature and pressure.The key principle of plate tectonics is that the lithosphere exists as separate and distinct tectonic plates, which ride on the fluid-like (visco-elastic solid) asthenosphere. Plate motions range up to a typical 10–40 mm/year (Mid-Atlantic Ridge; about as fast as fingernails grow), to about 160 mm/year (Nazca Plate; about as fast as hair grows).[4] The driving mechanism behind this movement is described below.

Tectonic lithosphere plates consist of lithospheric mantle overlain by either or both of two types of crustal material: oceanic crust (in older texts called sima from silicon and magnesium) and continental crust (sial from silicon and aluminium). Average oceanic lithosphere is typically 100 km (62 mi) thick;[5] its thickness is a function of its age: as time passes, it conductively cools and subjacent cooling mantle is added to its base. Because it is formed at mid-ocean ridges and spreads outwards, its thickness is therefore a function of its distance from the mid-ocean ridge where it was formed. For a typical distance that oceanic lithosphere must travel before being subducted, the thickness varies from about 6 km (4 mi) thick at mid-ocean ridges to greater than 100 km (62 mi) at subduction zones; for shorter or longer distances, the subduction zone (and therefore also the mean) thickness becomes smaller or larger, respectively.[6] Continental lithosphere is typically ~200 km thick, though this varies considerably between basins, mountain ranges, and stable cratonic interiors of continents. The two types of crust also differ in thickness, with continental crust being considerably thicker than oceanic (35 km vs. 6 km).[7]

The location where two plates meet is called a plate boundary. Plate boundaries are commonly associated with geological events such as earthquakes and the creation of topographic features such as mountains, volcanoes, mid-ocean ridges, and oceanic trenches. The majority of the world's active volcanoes occur along plate boundaries, with the Pacific Plate's Ring of Fire being the most active and widely known today. These boundaries are discussed in further detail below. Some volcanoes occur in the interiors of plates, and these have been variously attributed to internal plate deformation[8] and to mantle plumes.

As explained above, tectonic plates may include continental crust or oceanic crust, and most plates contain both. For example, the African Plate includes the continent and parts of the floor of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The distinction between oceanic crust and continental crust is based on their modes of formation. Oceanic crust is formed at sea-floor spreading centers, and continental crust is formed through arc volcanism and accretion of terranes through tectonic processes, though some of these terranes may contain ophiolite sequences, which are pieces of oceanic crust considered to be part of the continent when they exit the standard cycle of formation and spreading centers and subduction beneath continents. Oceanic crust is also denser than continental crust owing to their different compositions. Oceanic crust is denser because it has less silicon and more heavier elements ("mafic") than continental crust ("felsic").[9] As a result of this density stratification, oceanic crust generally lies below sea level (for example most of the Pacific Plate), while continental crust buoyantly projects above sea level (see the page isostasy for explanation of this principle).

Types of plate boundaries

Three types of plate boundaries exist,[10] with a fourth, mixed type, characterized by the way the plates move relative to each other. They are associated with different types of surface phenomena. The different types of plate boundaries are:[11][12]- Transform boundaries (Conservative) occur where two lithospheric plates slide, or perhaps more accurately, grind past each other along transform faults, where plates are neither created nor destroyed. The relative motion of the two plates is either sinistral (left side toward the observer) or dextral (right side toward the observer). Transform faults occur across a spreading center. Strong earthquakes can occur along a fault. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform boundary exhibiting dextral motion.

- Divergent boundaries (Constructive) occur where two plates slide apart from each other. At zones of ocean-to-ocean rifting, divergent boundaries form by seafloor spreading, allowing for the formation of new ocean basin. As the continent splits, the ridge forms at the spreading center, the ocean basin expands, and finally, the plate area increases causing many small volcanoes and/or shallow earthquakes. At zones of continent-to-continent rifting, divergent boundaries may cause new ocean basin to form as the continent splits, spreads, the central rift collapses, and ocean fills the basin. Active zones of Mid-ocean ridges (e.g., Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise), and continent-to-continent rifting (such as Africa's East African Rift and Valley, Red Sea) are examples of divergent boundaries.

- Convergent boundaries (Destructive) (or active margins) occur where two plates slide toward each other to form either a subduction zone (one plate moving underneath the other) or a continental collision. At zones of ocean-to-continent subduction (e.g. the Andes mountain range in South America, and the Cascade Mountains in Western United States), the dense oceanic lithosphere plunges beneath the less dense continent. Earthquakes then trace the path of the downward-moving plate as it descends into asthenosphere, a trench forms, and as the subducted plate partially melts, magma rises to form continental volcanoes. At zones of ocean-to-ocean subduction (e.g. Aleutian islands, Mariana islands, and the Japanese island arc), older, cooler, denser crust slips beneath less dense crust. This causes earthquakes and a deep trench to form in an arc shape. The upper mantle of the subducted plate then heats and magma rises to form curving chains of volcanic islands. Deep marine trenches are typically associated with subduction zones, and the basins that develop along the active boundary are often called "foreland basins". The subducting slab contains many hydrous minerals which release their water on heating. This water then causes the mantle to melt, producing volcanism. Closure of ocean basins can occur at continent-to-continent boundaries (e.g., Himalayas and Alps): collision between masses of granitic continental lithosphere; neither mass is subducted; plate edges are compressed, folded, uplifted.

- Plate boundary zones occur where the effects of the interactions are unclear, and the boundaries, usually occurring along a broad belt, are not well defined and may show various types of movements in different episodes.

Driving forces of plate motion

Plate motion based on Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite data from NASA JPL. The vectors show direction and magnitude of motion.

It is generally accepted that tectonic plates are able to move because of the relative density of oceanic lithosphere and the relative weakness of the asthenosphere. Dissipation of heat from the mantle is acknowledged to be the original source of the energy required to drive plate tectonics through convection or large scale upwelling and doming. The current view, though still a matter of some debate, asserts that as a consequence, a powerful source of plate motion is generated due to the excess density of the oceanic lithosphere sinking in subduction zones. When the new crust forms at mid-ocean ridges, this oceanic lithosphere is initially less dense than the underlying asthenosphere, but it becomes denser with age as it conductively cools and thickens. The greater density of old lithosphere relative to the underlying asthenosphere allows it to sink into the deep mantle at subduction zones, providing most of the driving force for plate movement. The weakness of the asthenosphere allows the tectonic plates to move easily towards a subduction zone.[13] Although subduction is thought to be the strongest force driving plate motions, it cannot be the only force since there are plates such as the North American Plate which are moving, yet are nowhere being subducted. The same is true for the enormous Eurasian Plate. The sources of plate motion are a matter of intensive research and discussion among scientists. One of the main points is that the kinematic pattern of the movement itself should be separated clearly from the possible geodynamic mechanism that is invoked as the driving force of the observed movement, as some patterns may be explained by more than one mechanism.[14] In short, the driving forces advocated at the moment can be divided into three categories based on the relationship to the movement: mantle dynamics related, gravity related (mostly secondary forces).

For much of the last quarter century, the leading theory of the driving force behind tectonic plate motions envisaged large scale convection currents in the upper mantle which are transmitted through the asthenosphere. This theory was launched by Arthur Holmes and some forerunners in the 1930s[15] and was immediately recognized as the solution for the acceptance of the theory as originally discussed in the papers of Alfred Wegener in the early years of the century. However, despite its acceptance, it was long debated in the scientific community because the leading ("fixist") theory still envisaged a static Earth without moving continents up until the major breakthroughs of the early sixties.

Two- and three-dimensional imaging of Earth's interior (seismic tomography) shows a varying lateral density distribution throughout the mantle. Such density variations can be material (from rock chemistry), mineral (from variations in mineral structures), or thermal (through thermal expansion and contraction from heat energy). The manifestation of this varying lateral density is mantle convection from buoyancy forces.[16]

How mantle convection directly and indirectly relates to plate motion is a matter of ongoing study and discussion in geodynamics. Somehow, this energy must be transferred to the lithosphere for tectonic plates to move. There are essentially two types of forces that are thought to influence plate motion: friction and gravity.

- Basal drag (friction): Plate motion driven by friction between the convection currents in the asthenosphere and the more rigid overlying lithosphere.

- Slab suction (gravity): Plate motion driven by local convection currents that exert a downward pull on plates in subduction zones at ocean trenches. Slab suction may occur in a geodynamic setting where basal tractions continue to act on the plate as it dives into the mantle (although perhaps to a greater extent acting on both the under and upper side of the slab).

In the theory of plume tectonics developed during the 1990s, a modified concept of mantle convection currents is used. It asserts that super plumes rise from the deeper mantle and are the drivers or substitutes of the major convection cells. These ideas, which find their roots in the early 1930s with the so-called "fixistic" ideas of the European and Russian Earth Science Schools, find resonance in the modern theories which envisage hot spots/mantle plumes which remain fixed and are overridden by oceanic and continental lithosphere plates over time and leave their traces in the geological record (though these phenomena are not invoked as real driving mechanisms, but rather as modulators). Modern theories that continue building on the older mantle doming concepts and see plate movements as a secondary phenomena are beyond the scope of this page and are discussed elsewhere (for example on the plume tectonics page).

Another theory is that the mantle flows neither in cells nor large plumes but rather as a series of channels just below the Earth's crust, which then provide basal friction to the lithosphere. This theory, called "surge tectonics", became quite popular in geophysics and geodynamics during the 1980s and 1990s.[17]

Forces related to gravity are usually invoked as secondary phenomena within the framework of a more general driving mechanism such as the various forms of mantle dynamics described above.

Gravitational sliding away from a spreading ridge: According to many authors, plate motion is driven by the higher elevation of plates at ocean ridges.[18] As oceanic lithosphere is formed at spreading ridges from hot mantle material, it gradually cools and thickens with age (and thus adds distance from the ridge). Cool oceanic lithosphere is significantly denser than the hot mantle material from which it is derived and so with increasing thickness it gradually subsides into the mantle to compensate the greater load. The result is a slight lateral incline with increased distance from the ridge axis.

This force is regarded as a secondary force and is often referred to as "ridge push". This is a misnomer as nothing is "pushing" horizontally and tensional features are dominant along ridges. It is more accurate to refer to this mechanism as gravitational sliding as variable topography across the totality of the plate can vary considerably and the topography of spreading ridges is only the most prominent feature. Other mechanisms generating this gravitational secondary force include flexural bulging of the lithosphere before it dives underneath an adjacent plate which produces a clear topographical feature that can offset, or at least affect, the influence of topographical ocean ridges, and mantle plumes and hot spots, which are postulated to impinge on the underside of tectonic plates.

Slab-pull: Current scientific opinion is that the asthenosphere is insufficiently competent or rigid to directly cause motion by friction along the base of the lithosphere. Slab pull is therefore most widely thought to be the greatest force acting on the plates. In this current understanding, plate motion is mostly driven by the weight of cold, dense plates sinking into the mantle at trenches.[19] Recent models indicate that trench suction plays an important role as well. However, as the North American Plate is nowhere being subducted, yet it is in motion presents a problem. The same holds for the African, Eurasian, and Antarctic plates.

Gravitational sliding away from mantle doming: According to older theories, one of the driving mechanisms of the plates is the existence of large scale asthenosphere/mantle domes which cause the gravitational sliding of lithosphere plates away from them. This gravitational sliding represents a secondary phenomenon of this basically vertically oriented mechanism. This can act on various scales, from the small scale of one island arc up to the larger scale of an entire ocean basin.[20]

Alfred Wegener, being a meteorologist, had proposed tidal forces and pole flight force as the main driving mechanisms behind continental drift; however, these forces were considered far too small to cause continental motion as the concept then was of continents plowing through oceanic crust.[21] Therefore, Wegener later changed his position and asserted that convection currents are the main driving force of plate tectonics in the last edition of his book in 1929.

However, in the plate tectonics context (accepted since the seafloor spreading proposals of Heezen, Hess, Dietz, Morley, Vine, and Matthews (see below) during the early 1960s), oceanic crust is suggested to be in motion with the continents which caused the proposals related to Earth rotation to be reconsidered. In more recent literature, these driving forces are:

- Tidal drag due to the gravitational force the Moon (and the Sun) exerts on the crust of the Earth[22]

- Global deformation of the geoid due to small displacements of rotational pole with respect to the Earth's crust;

- Other smaller deformation effects of the crust due to wobbles and spin movements of the Earth rotation on a smaller time scale.

- The Coriolis force[23][24]

- The centrifugal force, which is treated as a slight modification of gravity[23][24]:249

Of the many forces discussed in this paragraph, tidal force is still highly debated and defended as a possible principle driving force of plate tectonics. The other forces are only used in global geodynamic models not using plate tectonics concepts (therefore beyond the discussions treated in this section) or proposed as minor modulations within the overall plate tectonics model.

In 1973, George W. Moore[26] of the USGS and R. C. Bostrom[27] presented evidence for a general westward drift of the Earth's lithosphere with respect to the mantle. He concluded that tidal forces (the tidal lag or "friction") caused by the Earth's rotation and the forces acting upon it by the Moon are a driving force for plate tectonics. As the Earth spins eastward beneath the moon, the moon's gravity ever so slightly pulls the Earth's surface layer back westward, just as proposed by Alfred Wegener (see above). In a more recent 2006 study,[28] scientists reviewed and advocated these earlier proposed ideas. It has also been suggested recently in Lovett (2006) that this observation may also explain why Venus and Mars have no plate tectonics, as Venus has no moon and Mars' moons are too small to have significant tidal effects on the planet. In a recent paper,[29] it was suggested that, on the other hand, it can easily be observed that many plates are moving north and eastward, and that the dominantly westward motion of the Pacific ocean basins derives simply from the eastward bias of the Pacific spreading center (which is not a predicted manifestation of such lunar forces). In the same paper the authors admit, however, that relative to the lower mantle, there is a slight westward component in the motions of all the plates. They demonstrated though that the westward drift, seen only for the past 30 Ma, is attributed to the increased dominance of the steadily growing and accelerating Pacific plate. The debate is still open.

Relative significance of each driving force mechanism

The vector of a plate's motion is a function of all the forces acting on the plate; however, therein lies the problem regarding the degree to which each process contributes to the overall motion of each tectonic plate.The diversity of geodynamic settings and the properties of each plate result from the impact of the various processes actively driving each individual plate. One method of dealing with this problem is to consider the relative rate at which each plate is moving as well as the evidence related to the significance of each process to the overall driving force on the plate.

One of the most significant correlations discovered to date is that lithospheric plates attached to downgoing (subducting) plates move much faster than plates not attached to subducting plates. The Pacific plate, for instance, is essentially surrounded by zones of subduction (the so-called Ring of Fire) and moves much faster than the plates of the Atlantic basin, which are attached (perhaps one could say 'welded') to adjacent continents instead of subducting plates. It is thus thought that forces associated with the downgoing plate (slab pull and slab suction) are the driving forces which determine the motion of plates, except for those plates which are not being subducted.[19] The driving forces of plate motion continue to be active subjects of on-going research within geophysics and tectonophysics.

Development of the theory

Summary

In line with other previous and contemporaneous proposals, in 1912 the meteorologist Alfred Wegener amply described what he called continental drift, expanded in his 1915 book The Origin of Continents and Oceans[30] and the scientific debate started that would end up fifty years later in the theory of plate tectonics.[31] Starting from the idea (also expressed by his forerunners) that the present continents once formed a single land mass (which was called Pangea later on) that drifted apart, thus releasing the continents from the Earth's mantle and likening them to "icebergs" of low density granite floating on a sea of denser basalt.[32] Supporting evidence for the idea came from the dove-tailing outlines of South America's east coast and Africa's west coast, and from the matching of the rock formations along these edges. Confirmation of their previous contiguous nature also came from the fossil plants Glossopteris and Gangamopteris, and the therapsid or mammal-like reptile Lystrosaurus, all widely distributed over South America, Africa, Antarctica, India and Australia. The evidence for such an erstwhile joining of these continents was patent to field geologists working in the southern hemisphere. The South African Alex du Toit put together a mass of such information in his 1937 publication Our Wandering Continents, and went further than Wegener in recognising the strong links between the Gondwana fragments.

But without detailed evidence and a force sufficient to drive the movement, the theory was not generally accepted: the Earth might have a solid crust and mantle and a liquid core, but there seemed to be no way that portions of the crust could move around. Distinguished scientists, such as Harold Jeffreys and Charles Schuchert, were outspoken critics of continental drift.

Despite much opposition, the view of continental drift gained support and a lively debate started between "drifters" or "mobilists" (proponents of the theory) and "fixists" (opponents). During the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, the former reached important milestones proposing that convection currents might have driven the plate movements, and that spreading may have occurred below the sea within the oceanic crust. Concepts close to the elements now incorporated in plate tectonics were proposed by geophysicists and geologists (both fixists and mobilists) like Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, and Umbgrove.

One of the first pieces of geophysical evidence that was used to support the movement of lithospheric plates came from paleomagnetism. This is based on the fact that rocks of different ages show a variable magnetic field direction, evidenced by studies since the mid–nineteenth century. The magnetic north and south poles reverse through time, and, especially important in paleotectonic studies, the relative position of the magnetic north pole varies through time. Initially, during the first half of the twentieth century, the latter phenomenon was explained by introducing what was called "polar wander" (see apparent polar wander), i.e., it was assumed that the north pole location had been shifting through time. An alternative explanation, though, was that the continents had moved (shifted and rotated) relative to the north pole, and each continent, in fact, shows its own "polar wander path". During the late 1950s it was successfully shown on two occasions that these data could show the validity of continental drift: by Keith Runcorn in a paper in 1956,[33] and by Warren Carey in a symposium held in March 1956.[34]

The second piece of evidence in support of continental drift came during the late 1950s and early 60s from data on the bathymetry of the deep ocean floors and the nature of the oceanic crust such as magnetic properties and, more generally, with the development of marine geology[35] which gave evidence for the association of seafloor spreading along the mid-oceanic ridges and magnetic field reversals, published between 1959 and 1963 by Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine & Matthews, and Morley.[36]

Simultaneous advances in early seismic imaging techniques in and around Wadati-Benioff zones along the trenches bounding many continental margins, together with many other geophysical (e.g. gravimetric) and geological observations, showed how the oceanic crust could disappear into the mantle, providing the mechanism to balance the extension of the ocean basins with shortening along its margins.

All this evidence, both from the ocean floor and from the continental margins, made it clear around 1965 that continental drift was feasible and the theory of plate tectonics, which was defined in a series of papers between 1965 and 1967, was born, with all its extraordinary explanatory and predictive power. The theory revolutionized the Earth sciences, explaining a diverse range of geological phenomena and their implications in other studies such as paleogeography and paleobiology.

Continental drift

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, geologists assumed that the Earth's major features were fixed, and that most geologic features such as basin development and mountain ranges could be explained by vertical crustal movement, described in what is called the geosynclinal theory. Generally, this was placed in the context of a contracting planet Earth due to heat loss in the course of a relatively short geological time.It was observed as early as 1596 that the opposite coasts of the Atlantic Ocean—or, more precisely, the edges of the continental shelves—have similar shapes and seem to have once fitted together.[37]

Since that time many theories were proposed to explain this apparent complementarity, but the assumption of a solid Earth made these various proposals difficult to accept.[38]

The discovery of radioactivity and its associated heating properties in 1895 prompted a re-examination of the apparent age of the Earth.[39] This had previously been estimated by its cooling rate and assumption the Earth's surface radiated like a black body.[40] Those calculations had implied that, even if it started at red heat, the Earth would have dropped to its present temperature in a few tens of millions of years. Armed with the knowledge of a new heat source, scientists realized that the Earth would be much older, and that its core was still sufficiently hot to be liquid.

By 1915, after having published a first article in 1912,[41] Alfred Wegener was making serious arguments for the idea of continental drift in the first edition of The Origin of Continents and Oceans.[30] In that book (re-issued in four successive editions up to the final one in 1936), he noted how the east coast of South America and the west coast of Africa looked as if they were once attached. Wegener was not the first to note this (Abraham Ortelius, Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, Eduard Suess, Roberto Mantovani and Frank Bursley Taylor preceded him just to mention a few), but he was the first to marshal significant fossil and paleo-topographical and climatological evidence to support this simple observation (and was supported in this by researchers such as Alex du Toit). Furthermore, when the rock strata of the margins of separate continents are very similar it suggests that these rocks were formed in the same way, implying that they were joined initially. For instance, parts of Scotland and Ireland contain rocks very similar to those found in Newfoundland and New Brunswick. Furthermore, the Caledonian Mountains of Europe and parts of the Appalachian Mountains of North America are very similar in structure and lithology.

However, his ideas were not taken seriously by many geologists, who pointed out that there was no apparent mechanism for continental drift. Specifically, they did not see how continental rock could plow through the much denser rock that makes up oceanic crust. Wegener could not explain the force that drove continental drift, and his vindication did not come until after his death in 1930.

Floating continents, paleomagnetism, and seismicity zones

As it was observed early that although granite existed on continents, seafloor seemed to be composed of denser basalt, the prevailing concept during the first half of the twentieth century was that there were two types of crust, named "sial" (continental type crust) and "sima" (oceanic type crust). Furthermore, it was supposed that a static shell of strata was present under the continents. It therefore looked apparent that a layer of basalt (sial) underlies the continental rocks.

However, based on abnormalities in plumb line deflection by the Andes in Peru, Pierre Bouguer had deduced that less-dense mountains must have a downward projection into the denser layer underneath. The concept that mountains had "roots" was confirmed by George B. Airy a hundred years later, during study of Himalayan gravitation, and seismic studies detected corresponding density variations. Therefore, by the mid-1950s, the question remained unresolved as to whether mountain roots were clenched in surrounding basalt or were floating on it like an iceberg.

During the 20th century, improvements in and greater use of seismic instruments such as seismographs enabled scientists to learn that earthquakes tend to be concentrated in specific areas, most notably along the oceanic trenches and spreading ridges. By the late 1920s, seismologists were beginning to identify several prominent earthquake zones parallel to the trenches that typically were inclined 40–60° from the horizontal and extended several hundred kilometers into the Earth. These zones later became known as Wadati-Benioff zones, or simply Benioff zones, in honor of the seismologists who first recognized them, Kiyoo Wadati of Japan and Hugo Benioff of the United States. The study of global seismicity greatly advanced in the 1960s with the establishment of the Worldwide Standardized Seismograph Network (WWSSN)[42] to monitor the compliance of the 1963 treaty banning above-ground testing of nuclear weapons. The much improved data from the WWSSN instruments allowed seismologists to map precisely the zones of earthquake concentration worldwide.

Meanwhile, debates developed around the phenomena of polar wander. Since the early debates of continental drift, scientists had discussed and used evidence that polar drift had occurred because continents seemed to have moved through different climatic zones during the past. Furthermore, paleomagnetic data had shown that the magnetic pole had also shifted during time. Reasoning in an opposite way, the continents might have shifted and rotated, while the pole remained relatively fixed. The first time the evidence of magnetic polar wander was used to support the movements of continents was in a paper by Keith Runcorn in 1956,[33] and successive papers by him and his students Ted Irving (who was actually the first to be convinced of the fact that paleomagnetism supported continental drift) and Ken Creer.

This was immediately followed by a symposium in Tasmania in March 1956.[43] In this symposium, the evidence was used in the theory of an expansion of the global crust. In this hypothesis the shifting of the continents can be simply explained by a large increase in size of the Earth since its formation. However, this was unsatisfactory because its supporters could offer no convincing mechanism to produce a significant expansion of the Earth. Certainly there is no evidence that the moon has expanded in the past 3 billion years; other work would soon show that the evidence was equally in support of continental drift on a globe with a stable radius.

During the thirties up to the late fifties, works by Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, Umbgrove, and numerous others outlined concepts that were close or nearly identical to modern plate tectonics theory. In particular, the English geologist Arthur Holmes proposed in 1920 that plate junctions might lie beneath the sea, and in 1928 that convection currents within the mantle might be the driving force.[44] Often, these contributions are forgotten because:

- At the time, continental drift was not accepted.

- Some of these ideas were discussed in the context of abandoned fixistic ideas of a deforming globe without continental drift or an expanding Earth.

- They were published during an episode of extreme political and economic instability that hampered scientific communication.

- Many were published by European scientists and at first not mentioned or given little credit in the papers on sea floor spreading published by the American researchers in the 1960s.

Mid-oceanic ridge spreading and convection

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing utilizing the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's research vessel Atlantis and an array of instruments, confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the layer of sediments consisted of basalt, not the granite which is the main constituent of continents. They also found that the oceanic crust was much thinner than continental crust. All these new findings raised important and intriguing questions.[45]The new data that had been collected on the ocean basins also showed particular characteristics regarding the bathymetry. One of the major outcomes of these datasets was that all along the globe, a system of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the concept of the "Great Global Rift". This was described in the crucial paper of Bruce Heezen (1960),[46] which would trigger a real revolution in thinking. A profound consequence of seafloor spreading is that new crust was, and still is, being continually created along the oceanic ridges. Therefore, Heezen advocated the so-called "expanding Earth" hypothesis of S. Warren Carey (see above). So, still the question remained: how can new crust be continuously added along the oceanic ridges without increasing the size of the Earth? In reality, this question had been solved already by numerous scientists during the forties and the fifties, like Arthur Holmes, Vening-Meinesz, Coates and many others: The crust in excess disappeared along what were called the oceanic trenches, where so-called "subduction" occurred. Therefore, when various scientists during the early sixties started to reason on the data at their disposal regarding the ocean floor, the pieces of the theory quickly fell into place.

The question particularly intrigued Harry Hammond Hess, a Princeton University geologist and a Naval Reserve Rear Admiral, and Robert S. Dietz, a scientist with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey who first coined the term seafloor spreading. Dietz and Hess (the former published the same idea one year earlier in Nature,[47] but priority belongs to Hess who had already distributed an unpublished manuscript of his 1962 article by 1960)[48] were among the small handful who really understood the broad implications of sea floor spreading and how it would eventually agree with the, at that time, unconventional and unaccepted ideas of continental drift and the elegant and mobilistic models proposed by previous workers like Holmes.

In the same year, Robert R. Coats of the U.S. Geological Survey described the main features of island arc subduction in the Aleutian Islands. His paper, though little noted (and even ridiculed) at the time, has since been called "seminal" and "prescient". In reality, it actually shows that the work by the European scientists on island arcs and mountain belts performed and published during the 1930s up until the 1950s was applied and appreciated also in the United States.

If the Earth's crust was expanding along the oceanic ridges, Hess and Dietz reasoned like Holmes and others before them, it must be shrinking elsewhere. Hess followed Heezen, suggesting that new oceanic crust continuously spreads away from the ridges in a conveyor belt–like motion. And, using the mobilistic concepts developed before, he correctly concluded that many millions of years later, the oceanic crust eventually descends along the continental margins where oceanic trenches – very deep, narrow canyons – are formed, e.g. along the rim of the Pacific Ocean basin. The important step Hess made was that convection currents would be the driving force in this process, arriving at the same conclusions as Holmes had decades before with the only difference that the thinning of the ocean crust was performed using Heezen's mechanism of spreading along the ridges. Hess therefore concluded that the Atlantic Ocean was expanding while the Pacific Ocean was shrinking. As old oceanic crust is "consumed" in the trenches (like Holmes and others, he thought this was done by thickening of the continental lithosphere, not, as now understood, by underthrusting at a larger scale of the oceanic crust itself into the mantle), new magma rises and erupts along the spreading ridges to form new crust. In effect, the ocean basins are perpetually being "recycled," with the creation of new crust and the destruction of old oceanic lithosphere occurring simultaneously. Thus, the new mobilistic concepts neatly explained why the Earth does not get bigger with sea floor spreading, why there is so little sediment accumulation on the ocean floor, and why oceanic rocks are much younger than continental rocks.

Magnetic striping

As more and more of the seafloor was mapped during the 1950s, the magnetic variations turned out not to be random or isolated occurrences, but instead revealed recognizable patterns. When these magnetic patterns were mapped over a wide region, the ocean floor showed a zebra-like pattern: one stripe with normal polarity and the adjoining stripe with reversed polarity. The overall pattern, defined by these alternating bands of normally and reversely polarized rock, became known as magnetic striping, and was published by Ron G. Mason and co-workers in 1961, who did not find, though, an explanation for these data in terms of sea floor spreading, like Vine, Matthews and Morley a few years later.[49]

The discovery of magnetic striping called for an explanation. In the early 1960s scientists such as Heezen, Hess and Dietz had begun to theorise that mid-ocean ridges mark structurally weak zones where the ocean floor was being ripped in two lengthwise along the ridge crest (see the previous paragraph). New magma from deep within the Earth rises easily through these weak zones and eventually erupts along the crest of the ridges to create new oceanic crust. This process, at first denominated the "conveyer belt hypothesis" and later called seafloor spreading, operating over many millions of years continues to form new ocean floor all across the 50,000 km-long system of mid-ocean ridges.

Only four years after the maps with the "zebra pattern" of magnetic stripes were published, the link between sea floor spreading and these patterns was correctly placed, independently by Lawrence Morley, and by Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews, in 1963,[50] now called the Vine-Matthews-Morley hypothesis. This hypothesis linked these patterns to geomagnetic reversals and was supported by several lines of evidence:[51]

- the stripes are symmetrical around the crests of the mid-ocean ridges; at or near the crest of the ridge, the rocks are very young, and they become progressively older away from the ridge crest;

- the youngest rocks at the ridge crest always have present-day (normal) polarity;

- stripes of rock parallel to the ridge crest alternate in magnetic polarity (normal-reversed-normal, etc.), suggesting that they were formed during different epochs documenting the (already known from independent studies) normal and reversal episodes of the Earth's magnetic field.

Definition and refining of the theory

After all these considerations, Plate Tectonics (or, as it was initially called "New Global Tectonics") became quickly accepted in the scientific world, and numerous papers followed that defined the concepts:- In 1965, Tuzo Wilson who had been a promotor of the sea floor spreading hypothesis and continental drift from the very beginning[52] added the concept of transform faults to the model, completing the classes of fault types necessary to make the mobility of the plates on the globe work out.[53]

- A symposium on continental drift was held at the Royal Society of London in 1965 which must be regarded as the official start of the acceptance of plate tectonics by the scientific community, and which abstracts are issued as Blacket, Bullard & Runcorn (1965). In this symposium, Edward Bullard and co-workers showed with a computer calculation how the continents along both sides of the Atlantic would best fit to close the ocean, which became known as the famous "Bullard's Fit".

- In 1966 Wilson published the paper that referred to previous plate tectonic reconstructions, introducing the concept of what is now known as the "Wilson Cycle".[54]

- In 1967, at the American Geophysical Union's meeting, W. Jason Morgan proposed that the Earth's surface consists of 12 rigid plates that move relative to each other.[55]

- Two months later, Xavier Le Pichon published a complete model based on 6 major plates with their relative motions, which marked the final acceptance by the scientific community of plate tectonics.[56]

- In the same year, McKenzie and Parker independently presented a model similar to Morgan's using translations and rotations on a sphere to define the plate motions.[57]

Implications for biogeography

Continental drift theory helps biogeographers to explain the disjunct biogeographic distribution of present-day life found on different continents but having similar ancestors.[58] In particular, it explains the Gondwanan distribution of ratites and the Antarctic flora.Plate reconstruction

Reconstruction is used to establish past (and future) plate configurations, helping determine the shape and make-up of ancient supercontinents and providing a basis for paleogeography.Defining plate boundaries

Current plate boundaries are defined by their seismicity.[59] Past plate boundaries within existing plates are identified from a variety of evidence, such as the presence of ophiolites that are indicative of vanished oceans.[60]Past plate motions

Tectonic motion first began around three billion years ago.[61][why?]Various types of quantitative and semi-quantitative information are available to constrain past plate motions. The geometric fit between continents, such as between west Africa and South America is still an important part of plate reconstruction. Magnetic stripe patterns provide a reliable guide to relative plate motions going back into the Jurassic period.[62] The tracks of hotspots give absolute reconstructions, but these are only available back to the Cretaceous.[63] Older reconstructions rely mainly on paleomagnetic pole data, although these only constrain the latitude and rotation, but not the longitude. Combining poles of different ages in a particular plate to produce apparent polar wander paths provides a method for comparing the motions of different plates through time.[64] Additional evidence comes from the distribution of certain sedimentary rock types,[65] faunal provinces shown by particular fossil groups, and the position of orogenic belts.[63]

Formation and break-up of continents

The movement of plates has caused the formation and break-up of continents over time, including occasional formation of a supercontinent that contains most or all of the continents. The supercontinent Columbia or Nuna formed during a period of 2,000 to 1,800 million years ago and broke up about 1,500 to 1,300 million years ago.[66] The supercontinent Rodinia is thought to have formed about 1 billion years ago and to have embodied most or all of Earth's continents, and broken up into eight continents around 600 million years ago. The eight continents later re-assembled into another supercontinent called Pangaea; Pangaea broke up into Laurasia (which became North America and Eurasia) and Gondwana (which became the remaining continents).The Himalayas, the world's tallest mountain range, are assumed to have been formed by the collision of two major plates. Before uplift, they were covered by the Tethys Ocean.

Current plates

There are dozens of smaller plates, the seven largest of which are the Arabian, Caribbean, Juan de Fuca, Cocos, Nazca, Philippine Sea and Scotia.

The current motion of the tectonic plates is today determined by remote sensing satellite data sets, calibrated with ground station measurements.

Other celestial bodies (planets, moons)

The appearance of plate tectonics on terrestrial planets is related to planetary mass, with more massive planets than Earth expected to exhibit plate tectonics. Earth may be a borderline case, owing its tectonic activity to abundant water [67] (silica and water form a deep eutectic.)Venus

Venus shows no evidence of active plate tectonics. There is debatable evidence of active tectonics in the planet's distant past; however, events taking place since then (such as the plausible and generally accepted hypothesis that the Venusian lithosphere has thickened greatly over the course of several hundred million years) has made constraining the course of its geologic record difficult. However, the numerous well-preserved impact craters have been utilized as a dating method to approximately date the Venusian surface (since there are thus far no known samples of Venusian rock to be dated by more reliable methods). Dates derived are dominantly in the range 500 to 750 million years ago, although ages of up to 1,200 million years ago have been calculated. This research has led to the fairly well accepted hypothesis that Venus has undergone an essentially complete volcanic resurfacing at least once in its distant past, with the last event taking place approximately within the range of estimated surface ages. While the mechanism of such an impressive thermal event remains a debated issue in Venusian geosciences, some scientists are advocates of processes involving plate motion to some extent.One explanation for Venus's lack of plate tectonics is that on Venus temperatures are too high for significant water to be present.[68][69] The Earth's crust is soaked with water, and water plays an important role in the development of shear zones. Plate tectonics requires weak surfaces in the crust along which crustal slices can move, and it may well be that such weakening never took place on Venus because of the absence of water. However, some researchers[who?] remain convinced that plate tectonics is or was once active on this planet.

Mars

Mars is considerably smaller than Earth and Venus, and there is evidence for ice on its surface and in its crust.In the 1990s, it was proposed that Martian Crustal Dichotomy was created by plate tectonic processes.[70] Scientists today disagree, and think that it was created either by upwelling within the Martian mantle that thickened the crust of the Southern Highlands and formed Tharsis[71] or by a giant impact that excavated the Northern Lowlands.[72]

Valles Marineris may be a tectonic boundary.[73]

Observations made of the magnetic field of Mars by the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft in 1999 showed patterns of magnetic striping discovered on this planet. Some scientists interpreted these as requiring plate tectonic processes, such as seafloor spreading.[74] However, their data fail a "magnetic reversal test", which is used to see if they were formed by flipping polarities of a global magnetic field.[75]