From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Wasp | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Vespula germanica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Suborder | |

| Apocrita See text for explanation. |

|

A wasp is any insect of the order Hymenoptera and suborder Apocrita that is neither a bee nor an ant.[1] Almost every pest insect species has at least one wasp species that preys upon it or parasitizes it, making wasps critically important in natural control of their numbers, or natural biocontrol. Parasitic wasps are increasingly used in agricultural pest control as they prey mostly on pest insects and have little impact on crops.[2][3]

Taxonomy

The majority of wasp species (well over 100,000 species) are "parasitic" (technically known as parasitoids), and the ovipositor is used simply to lay eggs, often directly into the body of the host. The most familiar wasps belong to Aculeata, a "division" of Apocrita, whose ovipositors are adapted into a venomous sting, though many aculeate species do not sting. Aculeata also contains ants and bees, and many wasps are commonly mistaken for bees, and vice-versa. In a similar respect, insects called "velvet ants" (the family Mutillidae) are technically wasps.

The suborder Symphyta, known commonly as sawflies, differ from members of Apocrita by lacking a stinger and having a broader connection between the mesosoma and metasoma. In addition to this, Symphyta larvae are mostly herbivorous and "caterpillar-like", whereas those of Apocrita are largely predatory.

A much narrower and simpler but popular definition of the term wasp is any member of the aculeate family Vespidae, which includes (among others) the genera known in North America as yellow jackets (Vespula and Dolichovespula) and hornets (Vespa); in many countries outside of the Western Hemisphere, the vernacular usage of wasp is even further restricted to apply strictly to yellow jackets (e.g., the "common wasp").

Categorizations

The various species of wasps fall into one of two main categories: solitary wasps and social wasps. Adult solitary wasps live and operate alone, and most do not construct nests (below); all adult solitary wasps are fertile. By contrast, social wasps exist in colonies numbering up to several thousand individuals and build nests—but in some cases not all of the colony can reproduce. In some species, just the wasp queen and male wasps can mate, while the majority of the colony is made up of sterile female workers.Characteristics

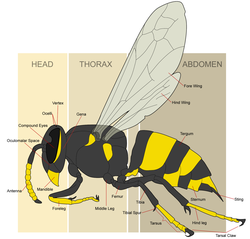

The basic morphology of a female yellowjacket wasp

The following characteristics are present in most wasps:

- Two pairs of wings (except wingless or brachypterous forms in all female Mutillidae, Bradynobaenidae, many male Agaonidae, many female Ichneumonidae, Braconidae, Tiphiidae, Scelionidae, Rhopalosomatidae, Eupelmidae, and various other families).

- An ovipositor, or stinger (which is only present in females because it derives from the ovipositor, a female sex organ).

- Few or no thickened hairs (in contrast to bees); except Mutillidae, Bradynobaenidae, Scoliidae.

- Nearly all wasps are terrestrial; only a few specialized parasitic groups are aquatic.

- Predators or parasitoids, mostly on other terrestrial insects; most species of Pompilidae (e.g. tarantula hawks), specialize in using spiders as prey, and various parasitic wasps use spiders or other arachnids as reproductive hosts.

Biology

Genetics

In wasps, as in other Hymenoptera, sexes are significantly genetically different. Females have 2n number of chromosomes and come about from fertilized eggs. Males, in contrast, have a haploid (n) number of chromosomes and develop from an unfertilized egg. Wasps store sperm inside their body and control its release for each individual egg as it is laid; if a female wishes to produce a male egg, she simply lays the egg without fertilizing it. Therefore, under most conditions in most species, wasps have complete voluntary control over the sex of their offspring.Anatomy and sex

Anatomically, there is a great deal of variation between different types of wasp. Like all insects, wasps have a hard exoskeleton covering their three main body parts. These parts are known as the head, mesosoma and metasoma. Wasps also have a constricted region joining the first and second segments of the abdomen (the first segment is part of the mesosoma, the second is part of the metasoma) known as the petiole. Like all insects, wasps have three sets of two legs. In addition to their compound eyes, wasps also have several simple eyes known as ocelli. These are typically arranged in a triangular formation just forward of an area of the head known as the vertex.It is possible to distinguish between sexes of some wasp species based on the number of divisions on their antennae. For example, male yellowjacket wasps have 13 divisions per antenna, while females have 12. Males can in some cases be differentiated from females by virtue of having an additional visible segment in the metasoma. The difference between sterile female worker wasps and queens also varies between species but generally the queen is noticeably larger than both males and other females.

Wasps can be differentiated from bees, which have a flattened hind basitarsus. Unlike bees, wasps generally lack plumose hairs.

Diet

Sand wasp (Bembix oculata, family Crabronidae) removing bodily fluids from a fly after paralysing it with the sting

Black wasp (Sphex pensylvanicus, family Sphecidae) large black wasp native to North America, feeding on the nectar of a fennel flower

Generally, wasps are parasites or parasitoids as larvae, and feed on nectar only as adults. Many wasps are predatory, using other insects (often paralyzed) as food for their larvae. In parasitic species, the first meals are almost always derived from the host in which the larvae grow.

Several types of social wasps are omnivorous, feeding on a variety of fallen fruit, nectar, and carrion. Some of these social wasps, such as yellow jackets, may scavenge for dead insects to provide for their young. In many social species, the larvae provide sweet secretions that are consumed by adults. Adult male wasps sometimes visit flowers to obtain nectar to feed on in much the same manner as honey bees. Furthermore some wasps, such as the Polistes fuscatus, may commonly return to locations to forage in which they have previously found prey.[4]

Role in ecosystem

Pollination

While the vast majority of wasps play no role in pollination, a few species can effectively transport pollen and therefore contribute for the pollination of several plant species, being potential or even efficient pollinators;[5] in a few cases such as figs pollinated by fig wasps, they are the only pollinators, and thus they are crucial to the survival of their host plants.Wasp parasitism

With most species, adult parasitic wasps themselves do not take any nutrients from their prey, and, much like bees, butterflies, and moths, those that do feed as adults typically derive all of their nutrition from nectar. Parasitic wasps are typically parasitoids, and extremely diverse in habits, many laying their eggs in inert stages of their host (egg or pupa), or sometimes paralyzing their prey by injecting it with venom through their ovipositor. They then insert one or more eggs into the host or deposit them upon the host externally. The host remains alive until the parasitoid larvae are mature, usually dying either when the parasitoids pupate, or when they emerge as adults.Wasps can also act as kleptoparasites, laying their eggs in the nests of other wasp species to exploit their parental care. Most such species attack hosts that provide provisions for their immature stages (such as paralyzed prey items), and they either consume the provisions intended for the host larva, or wait for the host to develop and then consume it before it reaches adulthood. An example of a true brood parasite is the paper wasp Polistes sulcifer, which lays its eggs in the nests of other paper wasps (specifically Polistes dominula), and whose larvae are then fed directly by the host.[6][7]

Nesting habits of aculeate wasps

The vast majority of wasp species are parasitoids, and do not make nests of any sort; nests are only constructed by wasps in the Aculeata. The type of nests produced by aculeate wasps vary widely, based on the species and location. Social wasps produce nests that are constructed predominantly from wood pulp. By contrast, solitary wasp nests are typically burrows excavated in a substrate (usually the soil, but also plant stems), or, if constructed, they are constructed from mud. Unlike honey bees, wasps have no wax-producing glands.Solitary species

The nesting habits of solitary wasps are more diverse than those of social wasps. Mud daubers and pollen wasps construct mud cells in sheltered places typically on the side of walls. Potter wasps similarly build vase-like nests from mud, often with multiple cells, attached to the twigs of trees or against walls. Most other predatory wasps burrow into soil or into plant stems, and many do not construct nests at all, but occupy naturally-occurring cavities, such as rock pores or crevices, small holes in wood or twigs. One egg is laid in each cell, which is then sealed, so there is no interaction between the larvae and the adults, unlike in social wasps. In some species, male eggs are selectively placed on smaller prey, leading to males being generally smaller than females.Social species

All species of social wasps construct their nests using some form of plant fiber (mostly wood pulp) as the primary material, though this can be supplemented with mud, plant secretions (e.g., resin), and secretions from the wasps themselves; multiple fibrous brood cells are constructed, arranged in a honeycombed pattern, and often surrounded by a larger protective envelope. Wood fibers are gathered locally from weathered wood, softened by chewing and mixing with saliva. The kind of timber used varies from one species to another, or one locality to another, and this can give many species a nest of distinctive color. The placement of nests can also vary from group to group; yellow jackets such as D. media and D. sylvestris prefer to nest in trees and shrubs, while P. exigua attach their nests on the underside of leaves and branches and Polistes erythrocephalus prefer to be close to a water source.[8] Other wasps, like A. multipicta and V. germanica, like to nest in cavities that include holes in the ground, spaces under homes, wall cavities or in lofts. While most species of wasps have nests with multiple combs, some species, such as Apoica flavissima, only have one comb.[9] The nests of some social wasps, such as hornets, are first constructed by the queen and reach about the size of a walnut before sterile female workers take over construction. The queen initially starts the nest by making a single layer or canopy and working outwards until she reaches the edges of the cavity. Beneath the canopy she constructs a stalk to which she can attach several cells; these cells are where the first eggs will be laid. The queen then continues to work outwards to the edges of the cavity after which she adds another tier. This process is repeated, each time adding a new tier until eventually enough female workers have been born and matured to take over construction of the nest leaving the queen to focus on reproduction. For this reason, the size of a nest is generally a good indicator of approximately how many female workers there are in the colony. Some hornets' nests eventually grow to be more than 50 centimetres (20 in) across. Social wasp colonies of this size often have populations of between three and ten thousand female workers, although a small proportion of nests are over 90 centimetres (3 ft) across and potentially contain upwards of twenty thousand workers and at least one queen. Nests close to one another at the beginning of the year have been observed to grow quickly and merge, and these structures can contain tens of thousands of workers. Most other social wasps do not construct their nests in tiers, but rather in flat or somewhat convex single combs.Social wasp reproductive cycle (temperate species only)

Wasps do not reproduce via mating flights like bees. Instead social wasps reproduce between a fertile queen and male wasp; in some cases queens may be fertilized by the sperm of several males. After successfully mating, the male's sperm cells are stored in a tightly packed ball inside the queen. The sperm cells are kept stored in a dormant state until they are needed the following spring. At a certain time of the year (often around autumn), the bulk of the wasp colony dies away, leaving only the young mated queens alive. During this time they leave the nest and find a suitable area to hibernate for the winter. The length of many species reproductive cycle depends on their location. Polistes erythrocephalus, for example, has a much longer (up to 3 months longer) cycle in temperate regions.[10]

First stage

After emerging from hibernation during early summer, the young queens search for a suitable nesting site. Upon finding an area for their colony, the queen constructs a basic wood fiber nest roughly the size of a walnut into which she will begin to lay |eggs.Second stage

The sperm that was stored earlier and kept dormant over winter is now used to fertilize the eggs being laid. The storage of sperm inside the queen allows her to lay a considerable number of fertilized eggs without the need for repeated mating with a male wasp. For this reason a single queen is capable of building an entire colony by herself. The queen initially raises the first several sets of wasp eggs until enough sterile female workers exist to maintain the offspring without her assistance. All of the eggs produced at this time are sterile female workers who will begin to construct a more elaborate nest around their queen as they grow in number.Third stage

By this time the nest size has expanded considerably and now numbers between several hundred and several thousand wasps. Towards the end of the summer, the queen begins to run out of stored sperm to fertilize more eggs. These eggs develop into fertile males and fertile female queens. The male drones then fly out of the nest and find a mate thus perpetuating the wasp reproductive cycle. In most species of social wasp the young queens mate in the vicinity of their home nest and do not travel like their male counterparts do. The young queens will then leave the colony to hibernate for the winter once the other worker wasps and founder queen have started to die off. After successfully mating with a young queen, the male drones die off as well. Generally, young queens and drones from the same nest do not mate with each other; this ensures more genetic variation within wasp populations, especially considering that all members of the colony are theoretically the direct genetic descendants of the founder queen and a single male drone. In practice, however, colonies can sometimes consist of the offspring of several male drones. Wasp queens generally (but not always) create new nests each year, probably because the weak construction of most nests render them uninhabitable after the winter.Unlike honey bee queens, wasp queens typically live for only one year. Also queen wasps do not organize their colony or have any raised status and hierarchical power within the social structure. They are more simply the reproductive element of the colony and the initial builder of the nest in those species that construct nests.

Social wasp caste structure

In many eusocial wasp species, hierarchy is determined by the individual's morphology. For example, within the species Vespula vulgaris, the brood that has gained the most nutrients and thus the largest, becomes the queen.However, not all social wasps have castes that are physically different in size and structure. For example, in many polistine paper wasps and stenogastrines, the castes of females are determined behaviorally, through dominance interactions, rather than having caste predetermined. Another example, in the social paper wasp Metapolybia cingulata the individuals have to be dissected in order to determine its role because the species lacks distinct morphological castes. All female wasps are potentially capable of becoming a colony's queen and this process is often determined by which female successfully lays eggs first and begins construction of the nest. Evidence suggests that females compete among each other by eating the eggs of other rival females. The queen may, in some cases, simply be the female that can eat the largest volume of eggs while ensuring that her own eggs survive (often achieved by laying the most). This process theoretically determines the strongest and most reproductively capable female and selects her as the queen. Once the first eggs have hatched, the subordinate females stop laying eggs and instead forage for the new queen and feed the young; that is, the competition largely ends, with the "losers" becoming workers, though if the dominant female dies, a new hierarchy may be established with a former "worker" acting as the replacement queen. Polistine nests are considerably smaller than many other social wasp nests, typically housing only around 250 wasps, compared to the several thousand common with yellowjackets, and stenogastrines have the smallest colonies of all, rarely with more than a dozen wasps in a mature colony.

Common families

- Agaonidae – fig wasps

- Chalcididae

- Chrysididae – cuckoo wasps

- Crabronidae – sand wasps and relatives, e.g. the Cicada killer wasp

- Cynipidae – gall wasps

- Encyrtidae

- Eulophidae

- Eupelmidae

- Ichneumonidae, and Braconidae

- Mutillidae – velvet ants

- Mymaridae – fairyflies

- Pompilidae – spider wasps

- Pteromalidae

- Scelionidae

- Scoliidae – scoliid wasps

- Sphecidae – digger wasps

- Tiphiidae – flower wasps

- Torymidae

- Trichogrammatidae

- Vespidae – common wasp, yellow jacket s, hornets, paper wasps (umbrella), potter wasps, pollen wasps