From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Intelligent design (ID) is a pseudoscientific argument for the existence of God, presented by its proponents as "an evidence-based scientific theory about life's origins".

Proponents claim that "certain features of the universe and of living

things are best explained by an intelligent cause, not an undirected

process such as natural selection." ID is a form of creationism that lacks empirical support and offers no testable or tenable hypotheses, and is therefore not science. The leading proponents of ID are associated with the Discovery Institute, a Christian, politically conservative think tank based in the United States.

Though the phrase intelligent design had featured previously in theological discussions of the argument from design, its first publication in its present use as an alternative term for creationism was in Of Pandas and People,

a 1989 creationist textbook intended for high school biology classes.

The term was substituted into drafts of the book, directly replacing

references to creation science and creationism, after the 1987 Supreme Court's Edwards v. Aguillard decision barred the teaching of creation science in public schools on constitutional grounds. From the mid-1990s, the intelligent design movement (IDM), supported by the Discovery Institute, advocated inclusion of intelligent design in public school biology curricula. This led to the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District

trial, which found that intelligent design was not science, that it

"cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious,

antecedents," and that the public school district's promotion of it

therefore violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

ID presents two main arguments against evolutionary explanations: irreducible complexity and specified complexity,

asserting that certain biological and informational features of living

things are too complex to be the result of natural selection. Detailed

scientific examination has rebutted several examples for which

evolutionary explanations are claimed to be impossible.

ID seeks to challenge the methodological naturalism inherent in modern science, though proponents concede that they have yet to produce a scientific theory. As a positive argument against evolution, ID proposes an analogy between natural systems and human artifacts, a version of the theological argument from design for the existence of God. ID proponents then conclude by analogy that the complex features, as defined by ID, are evidence of design. Critics of ID find a false dichotomy in the premise that evidence against evolution constitutes evidence for design.

History

Origin of the concept

In 1910, evolution was not a topic of major religious controversy in America, but in the 1920s, the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy in theology resulted in Fundamentalist Christian opposition to teaching evolution, and the origins of modern creationism.

Teaching of evolution was effectively suspended in U.S. public schools

until the 1960s, and when evolution was then reintroduced into the

curriculum, there was a series of court cases in which attempts were

made to get creationism taught alongside evolution in science classes. Young Earth creationists

(YEC) promoted creation science as "an alternative scientific

explanation of the world in which we live". This frequently invoked the argument from design to explain complexity in nature as demonstrating the existence of God.

The argument from design, also known as the teleological argument

or "argument from intelligent design", has been advanced in theology

for centuries.

It can be summarised briefly as "Wherever complex design exists, there

must have been a designer; nature is complex; therefore nature must have

had an intelligent designer." Thomas Aquinas presented it in his fifth proof of God's existence as a syllogism. In 1802, William Paley's Natural Theology presented examples of intricate purpose in organisms. His version of the watchmaker analogy argued that, in the same way that a watch has evidently been designed by a craftsman, complexity and adaptation

seen in nature must have been designed, and the perfection and

diversity of these designs shows the designer to be omnipotent, the Christian God. Like creation science, intelligent design centers on Paley's religious argument from design, but while Paley's natural theology was open to deistic

design through God-given laws, intelligent design seeks scientific

confirmation of repeated miraculous interventions in the history of

life. Creation science prefigured the intelligent design arguments of irreducible complexity, even featuring the bacterial flagellum.

In the United States, attempts to introduce creation science in schools

led to court rulings that it is religious in nature, and thus cannot be

taught in public school science classrooms. Intelligent design is also

presented as science, and shares other arguments with creation science

but avoids literal Biblical references to such things as the Flood story from the Book of Genesis or using Bible verses to age the Earth.

Barbara Forrest writes that the intelligent design movement began in 1984 with the book The Mystery of Life's Origin: Reassessing Current Theories, co-written by creationist Charles B. Thaxton, a chemist, with two other authors, and published by Jon A. Buell's Foundation for Thought and Ethics.

In March 1986, Stephen C. Meyer published a review of the book, discussing how information theory could suggest that messages transmitted by DNA in the cell show "specified complexity" specified by intelligence, and must have originated with an intelligent agent.

He also argued that science is based upon "foundational assumptions" of

naturalism which were as much a matter of faith as those of "creation

theory". In November of that year, Thaxton described his reasoning as a more sophisticated form of Paley's argument from design.

At the "Sources of Information Content in DNA" conference which Thaxton

held in 1988, he said that his intelligent cause view was compatible

with both metaphysical naturalism and supernaturalism.

Intelligent design avoids identifying or naming the intelligent designer—it merely states that one (or more) must exist—but leaders of the movement have said the designer is the Christian God. Whether this lack of specificity about the designer's identity in

public discussions is a genuine feature of the concept, or just a

posture taken to avoid alienating those who would separate religion from

the teaching of science, has been a matter of great debate between

supporters and critics of intelligent design. The Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District court ruling held the latter to be the case.

Origin of the term

Since the Middle Ages,

discussion of the religious "argument from design" or "teleological

argument" in theology, with its concept of "intelligent design", has

persistently referred to the theistic Creator God. Although ID

proponents chose this provocative label for their proposed alternative

to evolutionary explanations, they have de-emphasized their religious

antecedents and denied that ID is natural theology, while still presenting ID as supporting the argument for the existence of God.

While intelligent design proponents have pointed out past examples of the phrase intelligent design

that they said were not creationist and faith-based, they have failed

to show that these usages had any influence on those who introduced the

label in the intelligent design movement.

Variations on the phrase appeared in Young Earth creationist publications: a 1967 book co-written by Percival Davis referred to "design according to which basic organisms were created". In 1970, A. E. Wilder-Smith published The Creation of Life: A Cybernetic Approach to Evolution

which defended Paley's design argument with computer calculations of

the improbability of genetic sequences, which he said could not be

explained by evolution but required "the abhorred necessity of divine

intelligent activity behind nature", and that "the same problem would be

expected to beset the relationship between the designer behind nature

and the intelligently designed part of nature known as man." In a 1984

article as well as in his affidavit to Edwards v. Aguillard, Dean H. Kenyon

defended creation science by stating that "biomolecular systems require

intelligent design and engineering know-how", citing Wilder-Smith.

Creationist Richard B. Bliss used the phrase "creative design" in Origins: Two Models: Evolution, Creation (1976), and in Origins: Creation or Evolution

(1988) wrote that "while evolutionists are trying to find

non-intelligent ways for life to occur, the creationist insists that an

intelligent design must have been there in the first place." The first systematic use of the term, defined in a glossary and claimed to be other than creationism, was in Of Pandas and People, co-authored by Davis and Kenyon.

Of Pandas and People

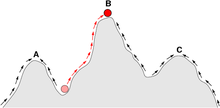

Use of the terms "creationism" versus "intelligent design" in sequential drafts of the book Of Pandas and People.

The most common modern use of the words "intelligent design" as a

term intended to describe a field of inquiry began after the United

States Supreme Court ruled in June 1987 in the case of Edwards v. Aguillard that it is unconstitutional for a state to require the teaching of creationism in public school science curricula.

A Discovery Institute report says that Charles B. Thaxton, editor of Pandas, had picked the phrase up from a NASA scientist, and thought, "That's just what I need, it's a good engineering term."

In two successive 1987 drafts of the book, over one hundred uses of the

root word "creation", such as "creationism" and "Creation Science",

were changed, almost without exception, to "intelligent design", while "creationists" was changed to "design proponents" or, in one instance, "cdesign proponentsists" [sic]. In June 1988, Thaxton held a conference titled "Sources of Information Content in DNA" in Tacoma, Washington. Stephen C. Meyer was at the conference, and later recalled that "The term intelligent design came up..." In December 1988 Thaxton decided to use the label "intelligent design" for his new creationist movement.

Of Pandas and People was published in 1989, and in

addition to including all the current arguments for ID, was the first

book to make systematic use of the terms "intelligent design" and

"design proponents" as well as the phrase "design theory", defining the

term intelligent design in a glossary and representing it as not being creationism. It thus represents the start of the modern intelligent design movement.

"Intelligent design" was the most prominent of around fifteen new terms

it introduced as a new lexicon of creationist terminology to oppose

evolution without using religious language.

It was the first place where the phrase "intelligent design" appeared

in its primary present use, as stated both by its publisher Jon A.

Buell, and by William A. Dembski in his expert witness report for Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District.

The National Center for Science Education

(NCSE) has criticized the book for presenting all of the basic

arguments of intelligent design proponents and being actively promoted

for use in public schools before any research had been done to support

these arguments. Although presented as a scientific textbook, philosopher of science Michael Ruse considers the contents "worthless and dishonest". An American Civil Liberties Union

lawyer described it as a political tool aimed at students who did not

"know science or understand the controversy over evolution and

creationism". One of the authors of the science framework used by

California schools, Kevin Padian, condemned it for its "sub-text", "intolerance for honest science" and "incompetence".

Concepts

Irreducible complexity

The term "irreducible complexity" was introduced by biochemist Michael Behe in his 1996 book Darwin's Black Box, though he had already described the concept in his contributions to the 1993 revised edition of Of Pandas and People.

Behe defines it as "a single system which is composed of several

well-matched interacting parts that contribute to the basic function,

wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to

effectively cease functioning".

Behe uses the analogy of a mousetrap to illustrate this concept. A

mousetrap consists of several interacting pieces—the base, the catch,

the spring and the hammer—all of which must be in place for the

mousetrap to work. Removal of any one piece destroys the function of the

mousetrap. Intelligent design advocates assert that natural selection

could not create irreducibly complex systems, because the selectable

function is present only when all parts are assembled. Behe argued that

irreducibly complex biological mechanisms include the bacterial

flagellum of E. coli, the blood clotting cascade, cilia, and the adaptive immune system.

Critics point out that the irreducible complexity argument

assumes that the necessary parts of a system have always been necessary

and therefore could not have been added sequentially.

They argue that something that is at first merely advantageous can

later become necessary as other components change. Furthermore, they

argue, evolution often proceeds by altering preexisting parts or by

removing them from a system, rather than by adding them. This is

sometimes called the "scaffolding objection" by an analogy with

scaffolding, which can support an "irreducibly complex" building until

it is complete and able to stand on its own.

Behe has acknowledged using "sloppy prose", and that his "argument against Darwinism does not add up to a logical proof." Irreducible complexity has remained a popular argument among advocates of intelligent design; in the Dover trial, the court held that "Professor Behe's claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and has been rejected by the scientific community at large."

Specified complexity

In 1986, Charles B. Thaxton, a physical chemist and creationist, used the term "specified complexity" from information theory

when claiming that messages transmitted by DNA in the cell were

specified by intelligence, and must have originated with an intelligent

agent.

The intelligent design concept of "specified complexity" was developed

in the 1990s by mathematician, philosopher, and theologian William A. Dembski.

Dembski states that when something exhibits specified complexity (i.e.,

is both complex and "specified", simultaneously), one can infer that it

was produced by an intelligent cause (i.e., that it was designed)

rather than being the result of natural processes. He provides the

following examples: "A single letter of the alphabet is specified

without being complex. A long sentence of random letters is complex

without being specified. A Shakespearean sonnet is both complex and specified."

He states that details of living things can be similarly characterized,

especially the "patterns" of molecular sequences in functional

biological molecules such as DNA.

Dembski defines complex specified information (CSI) as anything with a less than 1 in 10150 chance of occurring by (natural) chance. Critics say that this renders the argument a tautology:

complex specified information cannot occur naturally because Dembski

has defined it thus, so the real question becomes whether or not CSI

actually exists in nature.

The conceptual soundness of Dembski's specified complexity/CSI

argument has been discredited in the scientific and mathematical

communities. Specified complexity has yet to be shown to have wide applications in other fields, as Dembski asserts. John Wilkins and Wesley R. Elsberry characterize Dembski's "explanatory filter" as eliminative

because it eliminates explanations sequentially: first regularity, then

chance, finally defaulting to design. They argue that this procedure is

flawed as a model for scientific inference because the asymmetric way

it treats the different possible explanations renders it prone to making

false conclusions.

Richard Dawkins, another critic of intelligent design, argues in The God Delusion

(2006) that allowing for an intelligent designer to account for

unlikely complexity only postpones the problem, as such a designer would

need to be at least as complex.

Other scientists have argued that evolution through selection is better

able to explain the observed complexity, as is evident from the use of

selective evolution to design certain electronic, aeronautic and

automotive systems that are considered problems too complex for human

"intelligent designers".

Fine-tuned universe

Intelligent design proponents have also occasionally appealed to

broader teleological arguments outside of biology, most notably an

argument based on the fine-tuning of universal constants that make matter and life possible and which are argued not to be solely attributable to chance. These include the values of fundamental physical constants, the relative strength of nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity between fundamental particles, as well as the ratios of masses of such particles. Intelligent design proponent and Center for Science and Culture fellow Guillermo Gonzalez

argues that if any of these values were even slightly different, the

universe would be dramatically different, making it impossible for many chemical elements and features of the Universe, such as galaxies, to form.

Thus, proponents argue, an intelligent designer of life was needed to

ensure that the requisite features were present to achieve that

particular outcome.

Scientists have generally responded that these arguments are poorly supported by existing evidence. Victor J. Stenger and other critics say both intelligent design and the weak form of the anthropic principle are essentially a tautology; in his view, these arguments amount to the claim that life is able to exist because the Universe is able to support life. The claim of the improbability of a life-supporting universe has also been criticized as an argument by lack of imagination

for assuming no other forms of life are possible. Life as we know it

might not exist if things were different, but a different sort of life

might exist in its place. A number of critics also suggest that many of

the stated variables appear to be interconnected and that calculations

made by mathematicians and physicists suggest that the emergence of a

universe similar to ours is quite probable.

Intelligent designer

The contemporary intelligent design movement formulates its arguments in secular

terms and intentionally avoids identifying the intelligent agent (or

agents) they posit. Although they do not state that God is the designer,

the designer is often implicitly hypothesized to have intervened in a

way that only a god could intervene. Dembski, in The Design Inference (1998), speculates that an alien culture could fulfill these requirements. Of Pandas and People proposes that SETI illustrates an appeal to intelligent design in science. In 2000, philosopher of science Robert T. Pennock suggested the Raëlian UFO

religion as a real-life example of an extraterrestrial intelligent

designer view that "make[s] many of the same bad arguments against

evolutionary theory as creationists". The authoritative description of intelligent design, however, explicitly states that the Universe displays features of having been designed. Acknowledging the paradox,

Dembski concludes that "no intelligent agent who is strictly physical

could have presided over the origin of the universe or the origin of

life."

The leading proponents have made statements to their supporters that

they believe the designer to be the Christian God, to the exclusion of

all other religions.

Beyond the debate over whether intelligent design is scientific, a

number of critics argue that existing evidence makes the design

hypothesis appear unlikely, irrespective of its status in the world of

science. For example, Jerry Coyne asks why a designer would "give us a pathway for making vitamin C, but then destroy it by disabling one of its enzymes" (see pseudogene)

and why a designer would not "stock oceanic islands with reptiles,

mammals, amphibians, and freshwater fish, despite the suitability of

such islands for these species". Coyne also points to the fact that "the

flora and fauna on those islands resemble that of the nearest mainland,

even when the environments are very different" as evidence that species

were not placed there by a designer. Previously, in Darwin's Black Box,

Behe had argued that we are simply incapable of understanding the

designer's motives, so such questions cannot be answered definitively.

Odd designs could, for example, "...have been placed there by the

designer for a reason—for artistic reasons, for variety, to show off,

for some as-yet-undetected practical purpose, or for some unguessable

reason—or they might not."

Coyne responds that in light of the evidence, "either life resulted not

from intelligent design, but from evolution; or the intelligent

designer is a cosmic prankster who designed everything to make it look

as though it had evolved."

Intelligent design proponents such as Paul Nelson avoid the problem of poor design in nature

by insisting that we have simply failed to understand the perfection of

the design. Behe cites Paley as his inspiration, but he differs from

Paley's expectation of a perfect Creation and proposes that designers do

not necessarily produce the best design they can. Behe suggests that,

like a parent not wanting to spoil a child with extravagant toys, the

designer can have multiple motives for not giving priority to excellence

in engineering. He says that "Another problem with the argument from

imperfection is that it critically depends on a psychoanalysis of the

unidentified designer. Yet the reasons that a designer would or would

not do anything are virtually impossible to know unless the designer

tells you specifically what those reasons are." This reliance on inexplicable motives of the designer makes intelligent design scientifically untestable. Retired UC Berkeley law professor, author and intelligent design advocate Phillip E. Johnson puts forward a core definition that the designer creates for a purpose, giving the example that in his view AIDS was created to punish immorality and is not caused by HIV, but such motives cannot be tested by scientific methods.

Asserting the need for a designer of complexity also raises the question "What designed the designer?" Intelligent design proponents say that the question is irrelevant to or outside the scope of intelligent design.

Richard Wein counters that "...scientific explanations often create new

unanswered questions.

But, in assessing the value of an explanation,

these questions are not irrelevant. They must be balanced against the

improvements in our understanding which the explanation provides.

Invoking an unexplained being to explain the origin of other beings

(ourselves) is little more than question-begging. The new question raised by the explanation is as problematic as the question which the explanation purports to answer." Richard Dawkins sees the assertion that the designer does not need to be explained as a thought-terminating cliché. In the absence of observable, measurable evidence, the very question "What designed the designer?" leads to an infinite regression from which intelligent design proponents can only escape by resorting to religious creationism or logical contradiction.

Movement

The intelligent design movement is a direct outgrowth of the creationism of the 1980s.

The scientific and academic communities, along with a U.S. federal

court, view intelligent design as either a form of creationism or as a

direct descendant that is closely intertwined with traditional

creationism; and several authors explicitly refer to it as "intelligent design creationism".

The movement is headquartered in the Center for Science and Culture, established in 1996 as the creationist wing of the Discovery Institute to promote a religious agenda calling for broad social, academic and political changes. The Discovery Institute's intelligent design campaigns

have been staged primarily in the United States, although efforts have

been made in other countries to promote intelligent design. Leaders of

the movement say intelligent design exposes the limitations of

scientific orthodoxy and of the secular philosophy of naturalism.

Intelligent design proponents allege that science should not be limited

to naturalism and should not demand the adoption of a naturalistic

philosophy that dismisses out-of-hand any explanation that includes a supernatural cause. The overall goal of the movement is to "reverse the stifling dominance of the materialist worldview" represented by the theory of evolution in favor of "a science consonant with Christian and theistic convictions".

Phillip E. Johnson stated that the goal of intelligent design is to cast creationism as a scientific concept.

All leading intelligent design proponents are fellows or staff of the

Discovery Institute and its Center for Science and Culture.

Nearly all intelligent design concepts and the associated movement are

the products of the Discovery Institute, which guides the movement and

follows its wedge strategy while conducting its "Teach the Controversy" campaign and their other related programs.

Leading intelligent design proponents have made conflicting

statements regarding intelligent design. In statements directed at the

general public, they say intelligent design is not religious; when

addressing conservative Christian supporters, they state that

intelligent design has its foundation in the Bible. Recognizing the need for support, the Institute affirms its Christian, evangelistic orientation:

Alongside a focus on influential

opinion-makers, we also seek to build up a popular base of support among

our natural constituency, namely, Christians. We will do this primarily

through apologetics seminars. We intend these to encourage and equip

believers with new scientific evidences that support the faith, as well

as to "popularize" our ideas in the broader culture.

Barbara Forrest,

an expert who has written extensively on the movement, describes this

as being due to the Discovery Institute's obfuscating its agenda as a

matter of policy. She has written that the movement's "activities betray

an aggressive, systematic agenda for promoting not only intelligent

design creationism, but the religious worldview that undergirds it."

Religion and leading proponents

Although arguments for intelligent design by the intelligent design

movement are formulated in secular terms and intentionally avoid

positing the identity of the designer,

the majority of principal intelligent design advocates are publicly

religious Christians who have stated that, in their view, the designer

proposed in intelligent design is the Christian conception of God. Stuart Burgess, Phillip E. Johnson, William A. Dembski, and Stephen C. Meyer are evangelical Protestants; Michael Behe is a Roman Catholic; Paul Nelson supports young Earth creationism; and Jonathan Wells is a member of the Unification Church. Non-Christian proponents include David Klinghoffer, who is Jewish, Michael Denton and David Berlinski, who are agnostic, and Muzaffar Iqbal, a Pakistani-Canadian Muslim.

Phillip E. Johnson has stated that cultivating ambiguity by employing

secular language in arguments that are carefully crafted to avoid

overtones of theistic creationism

is a necessary first step for ultimately reintroducing the Christian

concept of God as the designer. Johnson explicitly calls for intelligent

design proponents to obfuscate their religious motivations so as to

avoid having intelligent design identified "as just another way of

packaging the Christian evangelical message."

Johnson emphasizes that "...the first thing that has to be done is to

get the Bible out of the discussion. ...This is not to say that the

biblical issues are unimportant; the point is rather that the time to

address them will be after we have separated materialist prejudice from

scientific fact."

The strategy of deliberately disguising the religious intent of intelligent design has been described by William A. Dembski in The Design Inference. In this work, Dembski lists a god or an "alien life force" as two possible options for the identity of the designer; however, in his book Intelligent Design: The Bridge Between Science and Theology (1999), Dembski states:

Christ is indispensable to any

scientific theory, even if its practitioners don't have a clue about

him. The pragmatics of a scientific theory can, to be sure, be pursued

without recourse to Christ. But the conceptual soundness of the theory

can in the end only be located in Christ.

Dembski also stated, "ID is part of God's general revelation [...] Not only does intelligent design rid us of this ideology [ materialism

], which suffocates the human spirit, but, in my personal experience,

I've found that it opens the path for people to come to Christ." Both Johnson and Dembski cite the Bible's Gospel of John as the foundation of intelligent design.

Barbara Forrest contends such statements reveal that leading

proponents see intelligent design as essentially religious in nature,

not merely a scientific concept that has implications with which their

personal religious beliefs happen to coincide. She writes that the leading proponents of intelligent design are closely allied with the ultra-conservative Christian Reconstructionism

movement. She lists connections of (current and former) Discovery

Institute Fellows Phillip E. Johnson, Charles B. Thaxton, Michael Behe, Richard Weikart, Jonathan Wells and Francis J. Beckwith to leading Christian Reconstructionist organizations, and the extent of the funding provided the Institute by Howard Ahmanson, Jr., a leading figure in the Reconstructionist movement.

Reaction from other creationist groups

Not all creationist organizations have embraced the intelligent

design movement. According to Thomas Dixon, "Religious leaders have come

out against ID too. An open letter affirming the compatibility of

Christian faith and the teaching of evolution, first produced in

response to controversies in Wisconsin in 2004, has now been signed by

over ten thousand clergy from different Christian denominations across

America." Hugh Ross of Reasons to Believe, a proponent of Old Earth creationism,

believes that the efforts of intelligent design proponents to divorce

the concept from Biblical Christianity make its hypothesis too vague. In

2002, he wrote: "Winning the argument for design without identifying

the designer yields, at best, a sketchy origins model. Such a model

makes little if any positive impact on the community of scientists and

other scholars. [...] ...the time is right for a direct approach, a

single leap into the origins fray. Introducing a biblically based,

scientifically verifiable creation model represents such a leap."

Likewise, two of the most prominent YEC organizations in the

world have attempted to distinguish their views from those of the

intelligent design movement. Henry M. Morris of the Institute for Creation Research

(ICR) wrote, in 1999, that ID, "even if well-meaning and effectively

articulated, will not work! It has often been tried in the past and has

failed, and it will fail today. The reason it won't work is because it

is not the Biblical method." According to Morris: "The evidence of

intelligent design ... must be either followed by or accompanied by a

sound presentation of true Biblical creationism if it is to be

meaningful and lasting." In 2002, Carl Wieland, then of Answers in Genesis

(AiG), criticized design advocates who, though well-intentioned, "'left

the Bible out of it'" and thereby unwittingly aided and abetted the

modern rejection of the Bible. Wieland explained that "AiG's major

'strategy' is to boldly, but humbly, call the church back to its

Biblical foundations ... [so] we neither count ourselves a part of this

movement nor campaign against it."

The unequivocal consensus in the scientific community is that intelligent design is not science and has no place in a science curriculum. The U.S. National Academy of Sciences

has stated that "creationism, intelligent design, and other claims of

supernatural intervention in the origin of life or of species are not

science because they are not testable by the methods of science." The U.S. National Science Teachers Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have termed it pseudoscience.[74]

Others in the scientific community have denounced its tactics, accusing

the ID movement of manufacturing false attacks against evolution, of

engaging in misinformation and misrepresentation about science, and

marginalizing those who teach it. More recently, in September 2012, Bill Nye warned that creationist views threaten science education and innovations in the United States.

In 2001, the Discovery Institute published advertisements under the heading "A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism", with the claim that listed scientists had signed this statement expressing skepticism:

We are skeptical of claims for the

ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the

complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian

theory should be encouraged.

The ambiguous statement did not exclude other known evolutionary

mechanisms, and most signatories were not scientists in relevant fields,

but starting in 2004 the Institute claimed the increasing number of

signatures indicated mounting doubts about evolution among scientists. The statement formed a key component of Discovery Institute campaigns to present intelligent design as scientifically valid by claiming that evolution lacks broad scientific support, with Institute members continued to cite the list through at least 2011. As part of a strategy to counter these claims, scientists organised Project Steve, which gained more signatories named Steve (or variants) than the Institute's petition, and a counter-petition, "A Scientific Support for Darwinism", which quickly gained similar numbers of signatories.

Polls

Several surveys were conducted prior to the December 2005 decision in Kitzmiller v. Dover School District, which sought to determine the level of support for intelligent design among certain groups. According to a 2005 Harris poll,

10% of adults in the United States viewed human beings as "so complex

that they required a powerful force or intelligent being to help create

them." Although Zogby polls

commissioned by the Discovery Institute show more support, these polls

suffer from considerable flaws, such as having a very low response rate

(248 out of 16,000), being conducted on behalf of an organization with

an expressed interest in the outcome of the poll, and containing leading questions.

The 2017 Gallup

creationism survey found that 38% of adults in the United States hold

the view that "God created humans in their present form at one time

within the last 10,000 years" when asked for their views on the origin

and development of human beings, which was noted as being at the lowest

level in 35 years.

Previously, a series of Gallup polls in the United States from 1982

through 2014 on "Evolution, Creationism, Intelligent Design" found

support for "human beings have developed over millions of years from

less advanced formed of life, but God guided the process" of between 31%

and 40%, support for "God created human beings in pretty much their

present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so" varied from

40% to 47%, and support for "human beings have developed over millions

of years from less advanced forms of life, but God had no part in the

process" varied from 9% to 19%. The polls also noted answers to a series

of more detailed questions.

Allegations of discrimination against ID proponents

There have been allegations that ID proponents have met

discrimination, such as being refused tenure or being harshly criticized

on the Internet. In the documentary film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed, released in 2008, host Ben Stein

presents five such cases. The film contends that the mainstream science

establishment, in a "scientific conspiracy to keep God out of the

nation's laboratories and classrooms", suppresses academics who believe

they see evidence of intelligent design in nature or criticize evidence

of evolution. Investigation into these allegations turned up alternative explanations for perceived persecution.

The film portrays intelligent design as motivated by science,

rather than religion, though it does not give a detailed definition of

the phrase or attempt to explain it on a scientific level. Other than

briefly addressing issues of irreducible complexity, Expelled examines it as a political issue. The scientific theory of evolution is portrayed by the film as contributing to fascism, the Holocaust, communism, atheism, and eugenics.

Expelled has been used in private screenings to legislators as part of the Discovery Institute intelligent design campaign for Academic Freedom bills.

Review screenings were restricted to churches and Christian groups, and

at a special pre-release showing, one of the interviewees, PZ Myers,

was refused admission. The American Association for the Advancement of

Science describes the film as dishonest and divisive propaganda aimed at

introducing religious ideas into public school science classrooms, and the Anti-Defamation League has denounced the film's allegation that evolutionary theory influenced the Holocaust.

The film includes interviews with scientists and academics who were

misled into taking part by misrepresentation of the topic and title of

the film. Skeptic Michael Shermer describes his experience of being repeatedly asked the same question without context as "surreal".

Criticism

Scientific criticism

Advocates of intelligent design seek to keep God and the Bible out of

the discussion, and present intelligent design in the language of

science as though it were a scientific hypothesis. For a theory to qualify as scientific, it is expected to be:

- Consistent

- Parsimonious (sparing in its proposed entities or explanations; see Occam's razor)

- Useful (describes and explains observed phenomena, and can be used in a predictive manner)

- Empirically testable and falsifiable (potentially confirmable or disprovable by experiment or observation)

- Based on multiple observations (often in the form of controlled, repeated experiments)

- Correctable and dynamic (modified in the light of observations that do not support it)

- Progressive (refines previous theories)

- Provisional or tentative (is open to experimental checking, and does not assert certainty)

For any theory, hypothesis, or conjecture to be considered

scientific, it must meet most, and ideally all, of these criteria. The

fewer criteria are met, the less scientific it is; if it meets only a

few or none at all, then it cannot be treated as scientific in any

meaningful sense of the word. Typical objections to defining intelligent

design as science are that it lacks consistency, violates the principle of parsimony, is not scientifically useful, is not falsifiable, is not empirically testable, and is not correctable, dynamic, progressive, or provisional.

Intelligent design proponents seek to change this fundamental basis of science by eliminating "methodological naturalism" from science and replacing it with what the leader of the intelligent design movement, Phillip E. Johnson, calls "theistic realism".

Intelligent design proponents argue that naturalistic explanations fail

to explain certain phenomena and that supernatural explanations provide

a very simple and intuitive explanation for the origins of life and the

universe. Many intelligent design followers believe that "scientism" is itself a religion that promotes secularism and materialism in an attempt to erase theism

from public life, and they view their work in the promotion of

intelligent design as a way to return religion to a central role in

education and other public spheres.

It has been argued that methodological naturalism is not an assumption of science, but a result of science well done: the God explanation is the least parsimonious, so according to Occam's razor, it cannot be a scientific explanation.

The failure to follow the procedures of scientific discourse and

the failure to submit work to the scientific community that withstands

scrutiny have weighed against intelligent design being accepted as valid

science.

The intelligent design movement has not published a properly

peer-reviewed article supporting ID in a scientific journal, and has

failed to publish supporting peer-reviewed research or data. The only article published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal that made a case for intelligent design was quickly withdrawn by the publisher for having circumvented the journal's peer-review standards. The Discovery Institute says that a number of intelligent design articles have been published in peer-reviewed journals,

but critics, largely members of the scientific community, reject this

claim and state intelligent design proponents have set up their own

journals with peer review that lack impartiality and rigor, consisting entirely of intelligent design supporters.

Further criticism stems from the fact that the phrase intelligent design makes use of an assumption of the quality of an observable intelligence, a concept that has no scientific consensus

definition. The characteristics of intelligence are assumed by

intelligent design proponents to be observable without specifying what

the criteria for the measurement of intelligence should be. Critics say

that the design detection methods proposed by intelligent design

proponents are radically different from conventional design detection,

undermining the key elements that make it possible as legitimate

science. Intelligent design proponents, they say, are proposing both

searching for a designer without knowing anything about that designer's

abilities, parameters, or intentions (which scientists do know when

searching for the results of human intelligence), as well as denying the

very distinction between natural/artificial design that allows

scientists to compare complex designed artifacts against the background

of the sorts of complexity found in nature.

Among a significant proportion of the general public in the

United States, the major concern is whether conventional evolutionary

biology is compatible with belief in God and in the Bible, and how this

issue is taught in schools.

The Discovery Institute's "Teach the Controversy" campaign promotes

intelligent design while attempting to discredit evolution in United

States public high school science courses.

The scientific community and science education organizations have

replied that there is no scientific controversy regarding the validity

of evolution and that the controversy exists solely in terms of religion

and politics.

Arguments from ignorance

Eugenie C. Scott, along with Glenn Branch and other critics, has argued that many points raised by intelligent design proponents are arguments from ignorance.

In the argument from ignorance, a lack of evidence for one view is

erroneously argued to constitute proof of the correctness of another

view. Scott and Branch say that intelligent design is an argument from

ignorance because it relies on a lack of knowledge for its conclusion:

lacking a natural explanation for certain specific aspects of evolution,

we assume intelligent cause. They contend most scientists would reply

that the unexplained is not unexplainable, and that "we don't know yet"

is a more appropriate response than invoking a cause outside science.

Particularly, Michael Behe's demands for ever more detailed explanations

of the historical evolution of molecular systems seem to assume a false

dichotomy, where either evolution or design is the proper explanation,

and any perceived failure of evolution becomes a victory for design.

Scott and Branch also contend that the supposedly novel contributions

proposed by intelligent design proponents have not served as the basis

for any productive scientific research.

In his conclusion to the Kitzmiller trial, Judge John E. Jones

III wrote that "ID is at bottom premised upon a false dichotomy, namely,

that to the extent evolutionary theory is discredited, ID is

confirmed." This same argument had been put forward to support creation

science at the McLean v. Arkansas

(1982) trial, which found it was "contrived dualism", the false premise

of a "two model approach". Behe's argument of irreducible complexity

puts forward negative arguments against evolution but does not make any

positive scientific case for intelligent design. It fails to allow for

scientific explanations continuing to be found, as has been the case

with several examples previously put forward as supposed cases of

irreducible complexity.

Possible theological implications

Intelligent design proponents often insist that their claims do not require a religious component. However, various philosophical and theological issues are naturally raised by the claims of intelligent design.

Intelligent design proponents attempt to demonstrate

scientifically that features such as irreducible complexity and

specified complexity could not arise through natural processes, and

therefore required repeated direct miraculous interventions by a

Designer (often a Christian concept of God). They reject the possibility

of a Designer who works merely through setting natural laws in motion

at the outset, in contrast to theistic evolution (to which even Charles Darwin was open).

Intelligent design is distinct because it asserts repeated miraculous

interventions in addition to designed laws. This contrasts with other

major religious traditions of a created world in which God's

interactions and influences do not work in the same way as physical

causes. The Roman Catholic tradition makes a careful distinction between

ultimate metaphysical explanations and secondary, natural causes.

The concept of direct miraculous intervention raises other

potential theological implications. If such a Designer does not

intervene to alleviate suffering even though capable of intervening for

other reasons, some imply the designer is not omnibenevolent (see problem of evil and related theodicy).

Further, repeated interventions imply that the original design

was not perfect and final, and thus pose a problem for any who believe

that the Creator's work had been both perfect and final. Intelligent design proponents seek to explain the problem of poor design in nature by insisting that we have simply failed to understand the perfection of the design (for example, proposing that vestigial organs

have unknown purposes), or by proposing that designers do not

necessarily produce the best design they can, and may have unknowable

motives for their actions.

In 2005 the director of the Vatican Observatory, the Jesuit astronomer George Coyne, set out theological reasons for accepting evolution in an August 2005 article in The Tablet,

and said that "Intelligent design isn't science even though it pretends

to be". It should not be included in the science curriculum for public

schools. "If you want to teach it in schools, intelligent design should

be taught when religion or cultural history is taught, not science." In 2006, he "condemned ID as a kind of ‘crude creationism’ which reduced God to a mere engineer."

God of the gaps

Intelligent design has also been characterized as a God-of-the-gaps argument, which has the following form:

- There is a gap in scientific knowledge.

- The gap is filled with acts of God (or intelligent designer) and

therefore proves the existence of God (or intelligent designer).

A God-of-the-gaps argument is the theological version of an argument from ignorance.

A key feature of this type of argument is that it merely answers

outstanding questions with explanations (often supernatural) that are

unverifiable and ultimately themselves subject to unanswerable

questions.

Historians of science observe that the astronomy of the earliest civilizations, although astonishing and incorporating mathematical constructions

far in excess of any practical value, proved to be misdirected and of

little importance to the development of science because they failed to

inquire more carefully into the mechanisms that drove the heavenly bodies across the sky. It was the Greek civilization

that first practiced science, although not yet as a formally defined

experimental science, but nevertheless an attempt to rationalize the

world of natural experience without recourse to divine intervention.

In this historically motivated definition of science any appeal to an

intelligent creator is explicitly excluded for the paralysing effect it

may have on scientific progress.

Legal challenges in the United States

Kitzmiller trial

Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District was the first direct challenge brought in the United States federal courts

against a public school district that required the presentation of

intelligent design as an alternative to evolution. The plaintiffs

successfully argued that intelligent design is a form of creationism,

and that the school board policy thus violated the Establishment Clause

of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Eleven parents of students in Dover, Pennsylvania, sued the Dover Area School District

over a statement that the school board required be read aloud in

ninth-grade science classes when evolution was taught. The plaintiffs

were represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Americans United for Separation of Church and State (AU) and Pepper Hamilton LLP. The National Center for Science Education acted as consultants for the plaintiffs. The defendants were represented by the Thomas More Law Center. The suit was tried in a bench trial from September 26 to November 4, 2005, before Judge John E. Jones III. Kenneth R. Miller, Kevin Padian, Brian Alters, Robert T. Pennock, Barbara Forrest and John F. Haught served as expert witnesses for the plaintiffs. Michael Behe, Steve Fuller and Scott Minnich served as expert witnesses for the defense.

On December 20, 2005, Judge Jones issued his 139-page findings of fact

and decision, ruling that the Dover mandate was unconstitutional, and

barring intelligent design from being taught in Pennsylvania's Middle

District public school science classrooms. On November 8, 2005, there

had been an election in which the eight Dover school board members who

voted for the intelligent design requirement were all defeated by

challengers who opposed the teaching of intelligent design in a science

class, and the current school board president stated that the board did

not intend to appeal the ruling.

In his finding of facts, Judge Jones made the following condemnation of the "Teach the Controversy" strategy:

Moreover, ID's backers have sought

to avoid the scientific scrutiny which we have now determined that it

cannot withstand by advocating that the controversy, but not ID itself, should be taught in science class. This tactic is at best disingenuous, and at worst a canard.

The goal of the IDM is not to encourage critical thought, but to foment

a revolution which would supplant evolutionary theory with ID.

Reaction to Kitzmiller ruling

Judge Jones himself anticipated that his ruling would be criticized, saying in his decision that:

Those who disagree with our holding

will likely mark it as the product of an activist judge. If so, they

will have erred as this is manifestly not an activist Court.

Rather, this case came to us as the result of the activism of an

ill-informed faction on a school board, aided by a national public

interest law firm eager to find a constitutional test case on ID, who in

combination drove the Board to adopt an imprudent and ultimately

unconstitutional policy. The breathtaking inanity of the Board's

decision is evident when considered against the factual backdrop which

has now been fully revealed through this trial. The students, parents,

and teachers of the Dover Area School District deserved better than to

be dragged into this legal maelstrom, with its resulting utter waste of

monetary and personal resources.

As Jones had predicted, John G. West, Associate Director of the Center for Science and Culture, said:

The Dover decision is an attempt by

an activist federal judge to stop the spread of a scientific idea and

even to prevent criticism of Darwinian evolution through

government-imposed censorship rather than open debate, and it won't

work. He has conflated Discovery Institute's position with that of the

Dover school board, and he totally misrepresents intelligent design and

the motivations of the scientists who research it.

Newspapers have noted that the judge is "a Republican and a churchgoer".

The decision has been examined in a search for flaws and

conclusions, partly by intelligent design supporters aiming to avoid

future defeats in court. In its Winter issue of 2007, the Montana Law Review published three articles.

In the first, David K. DeWolf, John G. West and Casey Luskin, all of the

Discovery Institute, argued that intelligent design is a valid

scientific theory, the Jones court should not have addressed the

question of whether it was a scientific theory, and that the Kitzmiller

decision will have no effect at all on the development and adoption of

intelligent design as an alternative to standard evolutionary theory. In the second Peter H. Irons

responded, arguing that the decision was extremely well reasoned and

spells the death knell for the intelligent design efforts to introduce

creationism in public schools, while in the third, DeWolf, et al., answer the points made by Irons.

However, fear of a similar lawsuit has resulted in other school boards

abandoning intelligent design "teach the controversy" proposals.

Anti-evolution legislation

A number of anti-evolution bills have been introduced in the United States Congress and State legislatures since 2001, based largely upon language drafted by the Discovery Institute for the Santorum Amendment.

Their aim has been to expose more students to articles and videos

produced by advocates of intelligent design that criticise evolution.

They have been presented as supporting "academic freedom",

on the supposition that teachers, students, and college professors face

intimidation and retaliation when discussing scientific criticisms of

evolution, and therefore require protection. Critics of the legislation

have pointed out that there are no credible scientific critiques of

evolution, and an investigation in Florida

of allegations of intimidation and retaliation found no evidence that

it had occurred. The vast majority of the bills have been unsuccessful,

with the one exception being Louisiana's Louisiana Science Education Act, which was enacted in 2008.

In April 2010, the American Academy of Religion issued Guidelines for Teaching About Religion in K‐12 Public Schools in the United States,

which included guidance that creation science or intelligent design

should not be taught in science classes, as "Creation science and

intelligent design represent worldviews that fall outside of the realm

of science that is defined as (and limited to) a method of inquiry based

on gathering observable and measurable evidence subject to specific

principles of reasoning." However, these worldviews as well as others

"that focus on speculation regarding the origins of life represent

another important and relevant form of human inquiry that is

appropriately studied in literature or social sciences courses. Such

study, however, must include a diversity of worldviews representing a

variety of religious and philosophical perspectives and must avoid

privileging one view as more legitimate than others."

Status outside the United States

Europe

In June 2007, the Council of Europe's Committee on Culture, Science and Education issued a report, The dangers of creationism in education,

which states "Creationism in any of its forms, such as 'intelligent

design', is not based on facts, does not use any scientific reasoning

and its contents are pathetically inadequate for science classes."

In describing the dangers posed to education by teaching creationism,

it described intelligent design as "anti-science" and involving "blatant

scientific fraud" and "intellectual deception" that "blurs the nature,

objectives and limits of science" and links it and other forms of

creationism to denialism.

On October 4, 2007, the Council of Europe's Parliamentary Assembly

approved a resolution stating that schools should "resist presentation

of creationist ideas in any discipline other than religion", including

"intelligent design", which it described as "the latest, more refined

version of creationism", "presented in a more subtle way". The

resolution emphasises that the aim of the report is not to question or

to fight a belief, but to "warn against certain tendencies to pass off a

belief as science".

In the United Kingdom, public education includes religious education as a compulsory subject, and there are many faith schools that teach the ethos of particular denominations. When it was revealed that a group called Truth in Science had distributed DVDs produced by Illustra Media featuring Discovery Institute fellows making the case for design in nature, and claimed they were being used by 59 schools, the Department for Education and Skills

(DfES) stated that "Neither creationism nor intelligent design are

taught as a subject in schools, and are not specified in the science

curriculum" (part of the National Curriculum, which does not apply to independent schools or to education in Scotland).

The DfES subsequently stated that "Intelligent design is not a

recognised scientific theory; therefore, it is not included in the

science curriculum", but left the way open for it to be explored in

religious education in relation to different beliefs, as part of a

syllabus set by a local Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education. In 2006, the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority produced a "Religious Education" model unit in which pupils can learn about religious and nonreligious

views about creationism, intelligent design and evolution by natural selection.

On June 25, 2007, the UK Government responded to an e-petition by

saying that creationism and intelligent design should not be taught as

science, though teachers would be expected to answer pupils' questions

within the standard framework of established scientific theories.

Detailed government "Creationism teaching guidance" for schools in

England was published on September 18, 2007. It states that "Intelligent

design lies wholly outside of science", has no underpinning scientific

principles, or explanations, and is not accepted by the science

community as a whole. Though it should not be taught as science, "Any

questions about creationism and intelligent design which arise in

science lessons, for example as a result of media coverage, could

provide the opportunity to explain or explore why they are not

considered to be scientific theories and, in the right context, why

evolution is considered to be a scientific theory." However, "Teachers

of subjects such as RE, history or citizenship may deal with creationism

and intelligent design in their lessons."

The British Centre for Science Education

lobbying group has the goal of "countering creationism within the UK"

and has been involved in government lobbying in the UK in this regard. Northern Ireland's Department for Education says that the curriculum provides an opportunity for alternative theories to be taught. The Democratic Unionist Party

(DUP)—which has links to fundamentalist Christianity—has been

campaigning to have intelligent design taught in science classes. A DUP

former Member of Parliament, David Simpson,

has sought assurances from the education minister that pupils will not

lose marks if they give creationist or intelligent design answers to

science questions. In 2007, Lisburn

city council voted in favor of a DUP recommendation to write to

post-primary schools asking what their plans are to develop teaching

material in relation to "creation, intelligent design and other theories

of origin".

Plans by Dutch Education Minister Maria van der Hoeven to "stimulate an academic debate" on the subject in 2005 caused a severe public backlash. After the 2006 elections, she was succeeded by Ronald Plasterk, described as a "molecular geneticist, staunch atheist and opponent of intelligent design". As a reaction on this situation in the Netherlands, the Director General of the Flemish Secretariat of Catholic Education (VSKO [nl]) in Belgium, Mieke Van Hecke [nl],

declared that: "Catholic scientists already accepted the theory of

evolution for a long time and that intelligent design and creationism

doesn't belong in Flemish Catholic schools. It's not the tasks of the

politics to introduce new ideas, that's task and goal of science."

Australia

The status of intelligent design in Australia is somewhat similar to that in the UK (see Education in Australia). In 2005, the Australian Minister for Education, Science and Training, Brendan Nelson,

raised the notion of intelligent design being taught in science

classes. The public outcry caused the minister to quickly concede that

the correct forum for intelligent design, if it were to be taught, is in

religion or philosophy classes. The Australian chapter of Campus Crusade for Christ distributed a DVD of the Discovery Institute's documentary Unlocking the Mystery of Life (2002) to Australian secondary schools. Tim Hawkes, the head of The King's School,

one of Australia's leading private schools, supported use of the DVD in

the classroom at the discretion of teachers and principals.

Relation to Islam

Muzaffar Iqbal, a notable Pakistani-Canadian Muslim, signed "A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism", a petition from the Discovery Institute. Ideas similar to intelligent design have been considered respected intellectual options among Muslims, and in Turkey many intelligent design books have been translated. In Istanbul in 2007, public meetings promoting intelligent design were sponsored by the local government, and David Berlinski of the Discovery Institute was the keynote speaker at a meeting in May 2007.

Relation to ISKCON

In 2011, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) Bhaktivedanta Book Trust published an intelligent design book titled Rethinking Darwin: A Vedic Study of Darwinism and Intelligent Design.

The book included contributions from intelligent design advocates

William A. Dembski, Jonathan Wells and Michael Behe as well as from

Hindu creationists Leif A. Jensen and Michael Cremo.