From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| HIV/AIDS |

|---|

| Other names | HIV disease, HIV infection |

|---|

|

| The red ribbon is a symbol for solidarity with HIV-positive people and those living with AIDS. |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, immunology |

|---|

| Symptoms | Early: Flu-like illness

Later: Large lymph nodes, fever, weight loss |

|---|

| Complications | Opportunistic infections, tumors |

|---|

| Duration | Lifelong |

|---|

| Causes | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

|---|

| Risk factors | Unprotected anal or vaginal sex, having another sexually transmitted infection, needle sharing, medical procedures involving unsterile cutting or piercing, and experiencing needlestick injury |

|---|

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests |

|---|

| Prevention | Safe sex, needle exchange, male circumcision, pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis |

|---|

| Treatment | Antiretroviral therapy |

|---|

| Prognosis | Near normal life expectancy with treatment

11 years life expectancy without treatment |

|---|

| Frequency | 64.4 million – 113 million total cases

1.5 million new cases (2021)

38.4 million living with HIV (2021) |

|---|

| Deaths | 40.1 million total deaths

650,000 (2021) |

|---|

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual may not notice any symptoms, or may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. Typically, this is followed by a prolonged incubation period with no symptoms. If the infection progresses, it interferes more with the immune system, increasing the risk of developing common infections such as tuberculosis, as well as other opportunistic infections, and tumors which are rare in people who have normal immune function. These late symptoms of infection are referred to as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). This stage is often also associated with unintended weight loss.

HIV is spread primarily by unprotected sex (including anal and vaginal sex), contaminated hypodermic needles or blood transfusions, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. Some bodily fluids, such as saliva, sweat, and tears, do not transmit the virus. Oral sex has little to no risk of transmitting the virus. Methods of prevention include safe sex, needle exchange programs, treating those who are infected, as well as both pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis. Disease in a baby can often be prevented by giving both the mother and child antiretroviral medication.

Recognized worldwide in the early 1980s, HIV/AIDS has had a large impact on society, both as an illness and as a source of discrimination. The disease also has large economic impacts. There are many misconceptions about HIV/AIDS, such as the belief that it can be transmitted by casual non-sexual contact. The disease has become subject to many controversies involving religion, including the Catholic Church's position not to support condom use as prevention.

It has attracted international medical and political attention as well

as large-scale funding since it was identified in the 1980s.

HIV made the jump from other primates to humans in west-central Africa in the early-to-mid 20th century. AIDS was first recognized by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1981 and its cause—HIV infection—was identified in the early part of the decade.

Between the first time AIDS was readily identified through 2021, the

disease is estimated to have caused at least 40 million deaths

worldwide. In 2021, there were 650,000 deaths and about 38 million people worldwide living with HIV. An estimated 20.6 million of these people live in eastern and southern Africa. HIV/AIDS is considered a pandemic—a disease outbreak which is present over a large area and is actively spreading.

The United States' National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Gates Foundation have pledged $200 million focused on developing a global cure for AIDS. While there is no cure or vaccine, antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy. Treatment is recommended as soon as the diagnosis is made. Without treatment, the average survival time after infection is 11 years.

Signs and symptoms

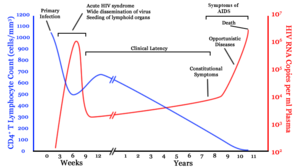

There are three main stages of HIV infection: acute infection, clinical latency, and AIDS.

Acute infection

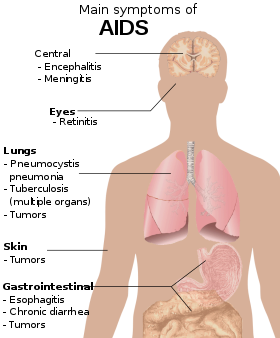

Main symptoms of acute HIV infection

The initial period following the contraction of HIV is called acute HIV, primary HIV or acute retroviral syndrome. Many individuals develop an influenza-like illness or a mononucleosis-like illness 2–4 weeks after exposure while others have no significant symptoms. Symptoms occur in 40–90% of cases and most commonly include fever, large tender lymph nodes, throat inflammation, a rash, headache, tiredness, and/or sores of the mouth and genitals. The rash, which occurs in 20–50% of cases, presents itself on the trunk and is maculopapular, classically. Some people also develop opportunistic infections at this stage. Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting or diarrhea may occur. Neurological symptoms of peripheral neuropathy or Guillain–Barré syndrome also occur. The duration of the symptoms varies, but is usually one or two weeks.

Owing to their nonspecific character, these symptoms are not often recognized

as signs of HIV infection. Even cases that do get seen by a family

doctor or a hospital are often misdiagnosed as one of the many common infectious diseases with overlapping symptoms. Thus, it is recommended that HIV be considered in people presenting with an unexplained fever who may have risk factors for the infection.

Clinical latency

The initial symptoms are followed by a stage called clinical latency, asymptomatic HIV, or chronic HIV. Without treatment, this second stage of the natural history of HIV infection can last from about three years to over 20 years (on average, about eight years).

While typically there are few or no symptoms at first, near the end of

this stage many people experience fever, weight loss, gastrointestinal

problems and muscle pains. Between 50% and 70% of people also develop persistent generalized lymphadenopathy,

characterized by unexplained, non-painful enlargement of more than one

group of lymph nodes (other than in the groin) for over three to six

months.

Although most HIV-1

infected individuals have a detectable viral load and in the absence of

treatment will eventually progress to AIDS, a small proportion (about

5%) retain high levels of CD4+ T cells (T helper cells) without antiretroviral therapy for more than five years. These individuals are classified as "HIV controllers" or long-term nonprogressors (LTNP).

Another group consists of those who maintain a low or undetectable

viral load without anti-retroviral treatment, known as "elite

controllers" or "elite suppressors". They represent approximately 1 in

300 infected persons.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is defined as an HIV infection with either a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells per µL or the occurrence of specific diseases associated with HIV infection. In the absence of specific treatment, around half of people infected with HIV develop AIDS within ten years. The most common initial conditions that alert to the presence of AIDS are pneumocystis pneumonia (40%), cachexia in the form of HIV wasting syndrome (20%), and esophageal candidiasis. Other common signs include recurrent respiratory tract infections.

Opportunistic infections may be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that are normally controlled by the immune system. Which infections occur depends partly on what organisms are common in the person's environment. These infections may affect nearly every organ system.

People with AIDS have an increased risk of developing various viral-induced cancers, including Kaposi's sarcoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer. Kaposi's sarcoma is the most common cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of people with HIV.

The second-most common cancer is lymphoma, which is the cause of death

of nearly 16% of people with AIDS and is the initial sign of AIDS in 3%

to 4%. Both these cancers are associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). Cervical cancer occurs more frequently in those with AIDS because of its association with human papillomavirus (HPV). Conjunctival cancer (of the layer that lines the inner part of eyelids and the white part of the eye) is also more common in those with HIV.

Additionally, people with AIDS frequently have systemic symptoms such as prolonged fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen lymph nodes, chills, weakness, and unintended weight loss. Diarrhea is another common symptom, present in about 90% of people with AIDS. They can also be affected by diverse psychiatric and neurological symptoms independent of opportunistic infections and cancers.

Transmission

Average per act risk of getting HIV

by exposure route to an infected source

| Exposure route

|

Chance of infection

|

| Blood transfusion

|

90%

|

| Childbirth (to child)

|

25%

|

| Needle-sharing injection drug use

|

0.67%

|

| Percutaneous needle stick

|

0.30%

|

| Receptive anal intercourse*

|

0.04–3.0%

|

| Insertive anal intercourse*

|

0.03%

|

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse*

|

0.05–0.30%

|

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse*

|

0.01–0.38%

|

| Receptive oral intercourse*§

|

0–0.04%

|

| Insertive oral intercourse*§

|

0–0.005%

|

* assuming no condom use

§ source refers to oral intercourse

performed on a man

|

HIV is spread by three main routes: sexual contact,

significant exposure to infected body fluids or tissues, and from

mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding (known as vertical transmission).[13] There is no risk of acquiring HIV if exposed to feces, nasal secretions, saliva, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, or vomit unless these are contaminated with blood.[52] It is also possible to be co-infected by more than one strain of HIV—a condition known as HIV superinfection.[53]

Sexual

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV is through sexual contact with an infected person.

However, an HIV-positive person who has an undetectable viral load as a

result of long-term treatment has effectively no risk of transmitting

HIV sexually.

The existence of functionally noncontagious HIV-positive people on

antiretroviral therapy was controversially publicized in the 2008 Swiss Statement, and has since become accepted as medically sound.

Globally, the most common mode of HIV transmission is via sexual contacts between people of the opposite sex; however, the pattern of transmission varies among countries. As of 2017, most HIV transmission in the United States occurred among men who had sex with men (82% of new HIV diagnoses among males aged 13 and older and 70% of total new diagnoses).

In the US, gay and bisexual men aged 13 to 24 accounted for an

estimated 92% of new HIV diagnoses among all men in their age group and

27% of new diagnoses among all gay and bisexual men.

With regard to unprotected

heterosexual contacts, estimates of the risk of HIV transmission per

sexual act appear to be four to ten times higher in low-income countries

than in high-income countries.

In low-income countries, the risk of female-to-male transmission is

estimated as 0.38% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.30%

per act; the equivalent estimates for high-income countries are 0.04%

per act for female-to-male transmission, and 0.08% per act for

male-to-female transmission.

The risk of transmission from anal intercourse is especially high,

estimated as 1.4–1.7% per act in both heterosexual and homosexual

contacts. While the risk of transmission from oral sex is relatively low, it is still present. The risk from receiving oral sex has been described as "nearly nil"; however, a few cases have been reported. The per-act risk is estimated at 0–0.04% for receptive oral intercourse. In settings involving prostitution

in low-income countries, risk of female-to-male transmission has been

estimated as 2.4% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.05%

per act.

Risk of transmission increases in the presence of many sexually transmitted infections and genital ulcers. Genital ulcers appear to increase the risk approximately fivefold. Other sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis, are associated with somewhat smaller increases in risk of transmission.

The viral load of an infected person is an important risk factor in both sexual and mother-to-child transmission.

During the first 2.5 months of an HIV infection a person's

infectiousness is twelve times higher due to the high viral load

associated with acute HIV. If the person is in the late stages of infection, rates of transmission are approximately eightfold greater.

Commercial sex workers (including those in pornography) have an increased likelihood of contracting HIV. Rough sex can be a factor associated with an increased risk of transmission. Sexual assault

is also believed to carry an increased risk of HIV transmission as

condoms are rarely worn, physical trauma to the vagina or rectum is

likely, and there may be a greater risk of concurrent sexually

transmitted infections.

Body fluids

CDC poster from 1989 highlighting the threat of AIDS associated with drug use

The second-most frequent mode of HIV transmission is via blood and blood products.

Blood-borne transmission can be through needle-sharing during

intravenous drug use, needle-stick injury, transfusion of contaminated

blood or blood product, or medical injections with unsterilized

equipment. The risk from sharing a needle during drug injection is between 0.63% and 2.4% per act, with an average of 0.8%.

The risk of acquiring HIV from a needle stick from an HIV-infected

person is estimated as 0.3% (about 1 in 333) per act and the risk

following mucous membrane exposure to infected blood as 0.09% (about 1 in 1000) per act. This risk may, however, be up to 5% if the introduced blood was from a person with a high viral load and the cut was deep. In the United States, intravenous drug users made up 12% of all new cases of HIV in 2009, and in some areas more than 80% of people who inject drugs are HIV-positive.

HIV is transmitted in about 90% of blood transfusions using infected blood.

In developed countries the risk of acquiring HIV from a blood

transfusion is extremely low (less than one in half a million) where

improved donor selection and HIV screening is performed; for example, in the UK the risk is reported at one in five million and in the United States it was one in 1.5 million in 2008. In low-income countries, only half of transfusions may be appropriately screened (as of 2008),

and it is estimated that up to 15% of HIV infections in these areas

come from transfusion of infected blood and blood products, representing

between 5% and 10% of global infections. It is possible to acquire HIV from organ and tissue transplantation, although this is rare because of screening.

Unsafe medical injections play a role in HIV spread in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2007, between 12% and 17% of infections in this region were attributed to medical syringe use. The World Health Organization estimates the risk of transmission as a result of a medical injection in Africa at 1.2%. Risks are also associated with invasive procedures, assisted delivery, and dental care in this area of the world.

People giving or receiving tattoos, piercings, and scarification are theoretically at risk of infection but no confirmed cases have been documented. It is not possible for mosquitoes or other insects to transmit HIV.

Mother-to-child

HIV can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, during

delivery, or through breast milk, resulting in the baby also contracting

HIV. As of 2008, vertical transmission accounted for about 90% of cases of HIV in children.

In the absence of treatment, the risk of transmission before or during

birth is around 20%, and in those who also breastfeed 35%. Treatment decreases this risk to less than 5%.

Antiretrovirals when taken by either the mother or the baby decrease the risk of transmission in those who do breastfeed. If blood contaminates food during pre-chewing it may pose a risk of transmission. If a woman is untreated, two years of breastfeeding results in an HIV/AIDS risk in her baby of about 17%.

Due to the increased risk of death without breastfeeding in many areas

in the developing world, the World Health Organization recommends either

exclusive breastfeeding or the provision of safe formula. All women known to be HIV-positive should be taking lifelong antiretroviral therapy.

Virology

Diagram of a HIV virion structure

HIV is the cause of the spectrum of disease known as HIV/AIDS. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells.

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus, part of the family Retroviridae. Lentiviruses share many morphological and biological

characteristics. Many species of mammals are infected by lentiviruses,

which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses

with a long incubation period. Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry into the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted (reverse transcribed) into double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase

that is transported along with the viral genome in the virus particle.

The resulting viral DNA is then imported into the cell nucleus and

integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase and host co-factors. Once integrated, the virus may become latent, allowing the virus and its host cell to avoid detection by the immune system. Alternatively, the virus may be transcribed,

producing new RNA genomes and viral proteins that are packaged and

released from the cell as new virus particles that begin the replication

cycle anew.

HIV is now known to spread between CD4+ T cells by two parallel routes: cell-free spread and cell-to-cell spread, i.e. it employs hybrid spreading mechanisms.

In the cell-free spread, virus particles bud from an infected T cell,

enter the blood/extracellular fluid and then infect another T cell

following a chance encounter. HIV can also disseminate by direct transmission from one cell to another by a process of cell-to-cell spread. The hybrid spreading mechanisms of HIV contribute to the virus's ongoing replication against antiretroviral therapies.

Two types of HIV

have been characterized: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was

originally discovered (and initially referred to also as LAV or

HTLV-III). It is more virulent, more infective,

and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. The lower

infectivity of HIV-2 as compared with HIV-1 implies that fewer people

exposed to HIV-2 will be infected per exposure. Because of its

relatively poor capacity for transmission, HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa.

Pathophysiology

After the virus enters the body, there is a period of rapid viral replication,

leading to an abundance of virus in the peripheral blood. During

primary infection, the level of HIV may reach several million virus

particles per milliliter of blood. This response is accompanied by a marked drop in the number of circulating CD4+ T cells. The acute viremia is almost invariably associated with activation of CD8+ T cells, which kill HIV-infected cells, and subsequently with antibody production, or seroconversion. The CD8+ T cell response is thought to be important in controlling virus levels, which peak and then decline, as the CD4+ T cell counts recover. A good CD8+ T cell response has been linked to slower disease progression and a better prognosis, though it does not eliminate the virus.

Ultimately, HIV causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T cells. This weakens the immune system and allows opportunistic infections.

T cells are essential to the immune response and without them, the body

cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases. During the acute phase, HIV-induced cell lysis and killing of infected cells by CD8+ T cells accounts for CD4+ T cell depletion, although apoptosis

may also be a factor. During the chronic phase, the consequences of

generalized immune activation coupled with the gradual loss of the

ability of the immune system to generate new T cells appear to account

for the slow decline in CD4+ T cell numbers.

Although the symptoms of immune deficiency characteristic of AIDS

do not appear for years after a person is infected, the bulk of CD4+

T cell loss occurs during the first weeks of infection, especially in

the intestinal mucosa, which harbors the majority of the lymphocytes

found in the body. The reason for the preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells is that the majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells express the CCR5 protein which HIV uses as a co-receptor to gain access to the cells, whereas only a small fraction of CD4+ T cells in the bloodstream do so. A specific genetic change that alters the CCR5 protein when present in both chromosomes very effectively prevents HIV-1 infection.

HIV seeks out and destroys CCR5 expressing CD4+ T cells during acute infection. A vigorous immune response eventually controls the infection and initiates the clinically latent phase. CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues remain particularly affected. Continuous HIV replication causes a state of generalized immune activation persisting throughout the chronic phase. Immune activation, which is reflected by the increased activation state of immune cells and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, results from the activity of several HIV gene products

and the immune response to ongoing HIV replication. It is also linked

to the breakdown of the immune surveillance system of the

gastrointestinal mucosal barrier caused by the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells during the acute phase of disease.

Diagnosis

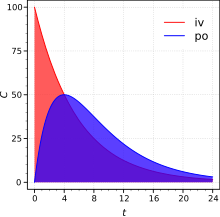

A generalized graph of the relationship between HIV copies (viral load) and CD4

+ T cell counts over the average course of untreated HIV infection.

CD4+ T Lymphocyte count (cells/mm³)

HIV RNA copies per mL of plasma

Days after exposure needed for the test to be accurate

| Blood test

|

Days

|

| Antibody test (rapid test, ELISA 3rd gen)

|

23–90

|

| Antibody and p24 antigen test (ELISA 4th gen)

|

18–45

|

| PCR

|

10–33

|

HIV/AIDS is diagnosed via laboratory testing and then staged based on the presence of certain signs or symptoms. HIV screening is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force for all people 15 years to 65 years of age, including all pregnant women.

Additionally, testing is recommended for those at high risk, which

includes anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted illness.

In many areas of the world, a third of HIV carriers only discover they

are infected at an advanced stage of the disease when AIDS or severe

immunodeficiency has become apparent.

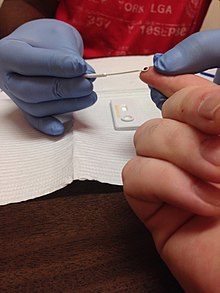

HIV testing

HIV rapid test being administered

Most people infected with HIV develop specific antibodies (i.e. seroconvert) within three to twelve weeks after the initial infection. Diagnosis of primary HIV before seroconversion is done by measuring HIV-RNA or p24 antigen. Positive results obtained by antibody or PCR testing are confirmed either by a different antibody or by PCR.

Antibody tests in children younger than 18 months are typically inaccurate, due to the continued presence of maternal antibodies. Thus HIV infection can only be diagnosed by PCR testing for HIV RNA or DNA, or via testing for the p24 antigen.

Much of the world lacks access to reliable PCR testing, and people in

many places simply wait until either symptoms develop or the child is

old enough for accurate antibody testing. In sub-Saharan Africa between 2007 and 2009, between 30% and 70% of the population were aware of their HIV status. In 2009, between 3.6% and 42% of men and women in sub-Saharan countries were tested; this represented a significant increase compared to previous years.

Classifications

Two main clinical staging systems are used to classify HIV and HIV-related disease for surveillance purposes: the WHO disease staging system for HIV infection and disease, and the CDC classification system for HIV infection.

The CDC's classification system is more frequently adopted in developed

countries. Since the WHO's staging system does not require laboratory

tests, it is suited to the resource-restricted conditions encountered in

developing countries, where it can also be used to help guide clinical

management. Despite their differences, the two systems allow a

comparison for statistical purposes.

The World Health Organization first proposed a definition for AIDS in 1986.

Since then, the WHO classification has been updated and expanded

several times, with the most recent version being published in 2007. The WHO system uses the following categories:

- Primary HIV infection: May be either asymptomatic or associated with acute retroviral syndrome

- Stage I: HIV infection is asymptomatic with a CD4+ T cell count (also known as CD4 count) greater than 500 per microlitre (µl or cubic mm) of blood. May include generalized lymph node enlargement.

- Stage II: Mild symptoms, which may include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. A CD4 count of less than 500/µl

- Stage III: Advanced symptoms, which may include unexplained chronic

diarrhea for longer than a month, severe bacterial infections including

tuberculosis of the lung, and a CD4 count of less than 350/µl

- Stage IV or AIDS: severe symptoms, which include toxoplasmosis of the brain, candidiasis of the esophagus, trachea, bronchi, or lungs, and Kaposi's sarcoma. A CD4 count of less than 200/µl

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also created a

classification system for HIV, and updated it in 2008 and 2014. This system classifies HIV infections based on CD4 count and clinical symptoms, and describes the infection in five groups. In those greater than six years of age it is:

- Stage 0: the time between a negative or indeterminate HIV test followed less than 180 days by a positive test.

- Stage 1: CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/µl and no AIDS-defining conditions.

- Stage 2: CD4 count 200 to 500 cells/µl and no AIDS-defining conditions.

- Stage 3: CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/µl or AIDS-defining conditions.

- Unknown: if insufficient information is available to make any of the above classifications.

For surveillance purposes, the AIDS diagnosis still stands even if, after treatment, the CD4+ T cell count rises to above 200 per µL of blood or other AIDS-defining illnesses are cured.

Prevention

AIDS clinic,

McLeod Ganj, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2010

Sexual contact

People

wearing AIDS awareness signs. On the left: "Facing AIDS a condom and a

pill at a time"; on the right: "I am Facing AIDS because people I ♥ are

infected"

Consistent condom use reduces the risk of HIV transmission by approximately 80% over the long term.

When condoms are used consistently by a couple in which one person is

infected, the rate of HIV infection is less than 1% per year. There is some evidence to suggest that female condoms may provide an equivalent level of protection. Application of a vaginal gel containing tenofovir (a reverse transcriptase inhibitor) immediately before sex seems to reduce infection rates by approximately 40% among African women. By contrast, use of the spermicide nonoxynol-9 may increase the risk of transmission due to its tendency to cause vaginal and rectal irritation.

Circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa "reduces the acquisition of HIV by heterosexual men by between 38% and 66% over 24 months". Owing to these studies, both the World Health Organization and UNAIDS

recommended male circumcision in 2007 as a method of preventing

female-to-male HIV transmission in areas with high rates of HIV. However, whether it protects against male-to-female transmission is disputed, and whether it is of benefit in developed countries and among men who have sex with men is undetermined.

Programs encouraging sexual abstinence do not appear to affect subsequent HIV risk. Evidence of any benefit from peer education is equally poor. Comprehensive sexual education provided at school may decrease high-risk behavior.

A substantial minority of young people continues to engage in high-risk

practices despite knowing about HIV/AIDS, underestimating their own

risk of becoming infected with HIV.

Voluntary counseling and testing people for HIV does not affect risky

behavior in those who test negative but does increase condom use in

those who test positive.

Enhanced family planning services appear to increase the likelihood of

women with HIV using contraception, compared to basic services. It is not known whether treating other sexually transmitted infections is effective in preventing HIV.

Pre-exposure

Antiretroviral treatment among people with HIV whose CD4 count ≤ 550

cells/µL is a very effective way to prevent HIV infection of their

partner (a strategy known as treatment as prevention, or TASP). TASP is associated with a 10- to 20-fold reduction in transmission risk. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with a daily dose of the medications tenofovir, with or without emtricitabine,

is effective in people at high risk including men who have sex with

men, couples where one is HIV-positive, and young heterosexuals in

Africa. It may also be effective in intravenous drug users, with a study finding a decrease in risk of 0.7 to 0.4 per 100 person years. The USPSTF, in 2019, recommended PrEP in those who are at high risk.

Universal precautions within the health care environment are believed to be effective in decreasing the risk of HIV. Intravenous drug use is an important risk factor, and harm reduction strategies such as needle-exchange programs and opioid substitution therapy appear effective in decreasing this risk.

Post-exposure

A course of antiretrovirals administered within 48 to 72 hours after

exposure to HIV-positive blood or genital secretions is referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The use of the single agent zidovudine reduces the risk of a HIV infection five-fold following a needle-stick injury. As of 2013, the prevention regimen recommended in the United States consists of three medications—tenofovir, emtricitabine and raltegravir—as this may reduce the risk further.

PEP treatment is recommended after a sexual assault when the perpetrator is known to be HIV-positive, but is controversial when their HIV status is unknown. The duration of treatment is usually four weeks

and is frequently associated with adverse effects—where zidovudine is

used, about 70% of cases result in adverse effects such as nausea (24%),

fatigue (22%), emotional distress (13%) and headaches (9%).

Mother-to-child

Programs to prevent the vertical transmission of HIV (from mothers to children) can reduce rates of transmission by 92–99%.

This primarily involves the use of a combination of antiviral

medications during pregnancy and after birth in the infant, and

potentially includes bottle feeding rather than breastfeeding.

If replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable

and safe, mothers should avoid breastfeeding their infants; however,

exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life

if this is not the case.

If exclusive breastfeeding is carried out, the provision of extended

antiretroviral prophylaxis to the infant decreases the risk of

transmission. In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to eradicate mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Vaccination

Currently there is no licensed vaccine for HIV or AIDS. The most effective vaccine trial to date, RV 144,

was published in 2009; it found a partial reduction in the risk of

transmission of roughly 30%, stimulating some hope in the research

community of developing a truly effective vaccine.

Treatment

There is currently no cure, nor an effective HIV vaccine. Treatment consists of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which slows progression of the disease. As of 2010, more than 6.6 million people were receiving HAART in low- and middle-income countries. Treatment also includes preventive and active treatment of opportunistic infections. As of July 2022, four people have been successfully cleared of HIV.

Rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy within one week of diagnosis

appear to improve treatment outcomes in low and medium-income settings

and is recommend for newly diagnosed HIV patients.

Antiviral therapy

Current HAART options are combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of

at least three medications belonging to at least two types, or

"classes", of antiretroviral agents. Initially, treatment is typically a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) plus two nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). Typical NRTIs include: zidovudine (AZT) or tenofovir (TDF) and lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC). As of 2019, dolutegravir/lamivudine/tenofovir is listed by the World Health Organization as the first-line treatment for adults, with tenofovir/lamivudine/efavirenz as an alternative. Combinations of agents that include protease inhibitors (PI) are used if the above regimen loses effectiveness.

The World Health Organization and the United States recommend

antiretrovirals in people of all ages (including pregnant women) as soon

as the diagnosis is made, regardless of CD4 count. Once treatment is begun, it is recommended that it is continued without breaks or "holidays". Many people are diagnosed only after treatment ideally should have begun. The desired outcome of treatment is a long-term plasma HIV-RNA count below 50 copies/mL.

Levels to determine if treatment is effective are initially recommended

after four weeks and once levels fall below 50 copies/mL checks every

three to six months are typically adequate. Inadequate control is deemed to be greater than 400 copies/mL. Based on these criteria treatment is effective in more than 95% of people during the first year.

Benefits of treatment include a decreased risk of progression to AIDS and a decreased risk of death. In the developing world, treatment also improves physical and mental health. With treatment, there is a 70% reduced risk of acquiring tuberculosis.

Additional benefits include a decreased risk of transmission of the

disease to sexual partners and a decrease in mother-to-child

transmission. The effectiveness of treatment depends to a large part on compliance. Reasons for non-adherence to treatment include poor access to medical care, inadequate social supports, mental illness and drug abuse. The complexity of treatment regimens (due to pill numbers and dosing frequency) and adverse effects may reduce adherence. Even though cost is an important issue with some medications, 47% of those who needed them were taking them in low- and middle-income countries as of 2010, and the rate of adherence is similar in low-income and high-income countries.

Specific adverse events are related to the antiretroviral agent taken. Some relatively common adverse events include: lipodystrophy syndrome, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, especially with protease inhibitors. Other common symptoms include diarrhea, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Newer recommended treatments are associated with fewer adverse effects. Certain medications may be associated with birth defects and therefore may be unsuitable for women hoping to have children.

Treatment recommendations for children are somewhat different

from those for adults. The World Health Organization recommends treating

all children less than five years of age; children above five are

treated like adults.

The United States guidelines recommend treating all children less than

12 months of age and all those with HIV RNA counts greater than

100,000 copies/mL between one year and five years of age.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended the granting of marketing authorizations for two new antiretroviral (ARV) medicines, rilpivirine (Rekambys) and cabotegravir (Vocabria), to be used together for the treatment of people with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. The two medicines are the first ARVs that come in a long-acting injectable formulation. This means that instead of daily pills, people receive intramuscular injections monthly or every two months.

The combination of Rekambys and Vocabria injection is intended

for maintenance treatment of adults who have undetectable HIV levels in

the blood (viral load less than 50 copies/ml) with their current ARV

treatment, and when the virus has not developed resistance to a certain

class of anti-HIV medicines called non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase

inhibitors (NNRTIs) and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INIs).

Cabotegravir combined with rilpivirine

(Cabenuva) is a complete regimen for the treatment of human

immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in adults to replace a

current antiretroviral regimen in those who are virologically suppressed

on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure

and with no known or suspected resistance to either cabotegravir or rilpivirine.

Opportunistic infections

Measures to prevent opportunistic infections are effective in many

people with HIV/AIDS. In addition to improving current disease,

treatment with antiretrovirals reduces the risk of developing additional

opportunistic infections.

Adults and adolescents who are living with HIV (even on

anti-retroviral therapy) with no evidence of active tuberculosis in

settings with high tuberculosis burden should receive isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT); the tuberculin skin test can be used to help decide if IPT is needed. Children with HIV may benefit from screening for tuberculosis. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for all people at risk of HIV before they become infected; however, it may also be given after infection.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

prophylaxis between four and six weeks of age, and ceasing

breastfeeding of infants born to HIV-positive mothers, is recommended in

resource-limited settings.

It is also recommended to prevent PCP when a person's CD4 count is

below 200 cells/uL and in those who have or have previously had PCP. People with substantial immunosuppression are also advised to receive prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and MAC. Appropriate preventive measures reduced the rate of these infections by 50% between 1992 and 1997. Influenza vaccination and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine are often recommended in people with HIV/AIDS with some evidence of benefit.

Diet

The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued recommendations regarding nutrient requirements in HIV/AIDS. A generally healthy diet is promoted. Dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels by HIV-infected adults is recommended by the WHO; higher intake of vitamin A, zinc, and iron can produce adverse effects in HIV-positive adults, and is not recommended unless there is documented deficiency.

Dietary supplementation for people who are infected with HIV and who

have inadequate nutrition or dietary deficiencies may strengthen their

immune systems or help them recover from infections; however, evidence

indicating an overall benefit in morbidity or reduction in mortality is

not consistent.

People with HIV/AIDS are up to four times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those who are not tested positive with the virus.

Evidence for supplementation with selenium is mixed with some tentative evidence of benefit. For pregnant and lactating women with HIV, multivitamin supplement improves outcomes for both mothers and children.

If the pregnant or lactating mother has been advised to take

anti-retroviral medication to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission,

multivitamin supplements should not replace these treatments. There is some evidence that vitamin A supplementation in children with an HIV infection reduces mortality and improves growth.

Alternative medicine

In the US, approximately 60% of people with HIV use various forms of complementary or alternative medicine, whose effectiveness has not been established. There is not enough evidence to support the use of herbal medicines. There is insufficient evidence to recommend or support the use of medical cannabis to try to increase appetite or weight gain.

Prognosis

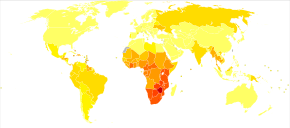

Deaths due to HIV/AIDS per million people in 2012:

0

1–4

5–12

13–34

35–61

62–134

135–215

216–458

459–1,402

1,403–5,828

HIV/AIDS has become a chronic rather than an acutely fatal disease in many areas of the world. Prognosis varies between people, and both the CD4 count and viral load are useful for predicted outcomes.

Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is

estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype. After the diagnosis of AIDS, if treatment is not available, survival ranges between 6 and 19 months. HAART

and appropriate prevention of opportunistic infections reduces the

death rate by 80%, and raises the life expectancy for a newly diagnosed

young adult to 20–50 years. This is between two thirds and nearly that of the general population. If treatment is started late in the infection, prognosis is not as good: for example, if treatment is begun following the diagnosis of AIDS, life expectancy is ~10–40 years. Half of infants born with HIV die before two years of age without treatment.

Disability-adjusted life year for HIV and AIDS per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2004:

| no data ≤ 10 10–25 25–50 50–100 | 100–500 500–1000 1,000–2,500 2,500–5,000 5,000–7500 | 7,500–10,000 10,000–50,000 ≥ 50,000 |

The primary causes of death from HIV/AIDS are opportunistic infections and cancer, both of which are frequently the result of the progressive failure of the immune system. Risk of cancer appears to increase once the CD4 count is below 500/μL.

The rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between

individuals and has been shown to be affected by a number of factors

such as a person's susceptibility and immune function; their access to health care, the presence of co-infections; and the particular strain (or strains) of the virus involved.

Tuberculosis

co-infection is one of the leading causes of sickness and death in

those with HIV/AIDS being present in a third of all HIV-infected people

and causing 25% of HIV-related deaths. HIV is also one of the most important risk factors for tuberculosis. Hepatitis C is another very common co-infection where each disease increases the progression of the other. The two most common cancers associated with HIV/AIDS are Kaposi's sarcoma and AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Other cancers that are more frequent include anal cancer, Burkitt's lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer.

Even with anti-retroviral treatment, over the long term HIV-infected people may experience neurocognitive disorders, osteoporosis, neuropathy, cancers, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease. Some conditions, such as lipodystrophy, may be caused both by HIV and its treatment.

Epidemiology

Percentage of people with HIV/AIDS

Trends in new cases and deaths per year from HIV/AIDS

Some authors consider HIV/AIDS a global pandemic. As of 2016, approximately 36.7 million people worldwide have HIV, the number of new infections that year being about 1.8 million. This is down from 3.1 million new infections in 2001. Slightly over half the infected population are women and 2.1 million are children. It resulted in about 1 million deaths in 2016, down from a peak of 1.9 million in 2005.

Sub-Saharan Africa

is the region most affected. In 2010, an estimated 68% (22.9 million)

of all HIV cases and 66% of all deaths (1.2 million) occurred in this

region. This means that about 5% of the adult population is infected and it is believed to be the cause of 10% of all deaths in children. Here, in contrast to other regions, women comprise nearly 60% of cases. South Africa has the largest population of people with HIV of any country in the world at 5.9 million. Life expectancy

has fallen in the worst-affected countries due to HIV/AIDS; for

example, in 2006 it was estimated that it had dropped from 65 to 35

years in Botswana. Mother-to-child transmission in Botswana and South Africa, as of 2013,

has decreased to less than 5%, with improvement in many other African

nations due to improved access to antiretroviral therapy.

South & South East Asia

is the second most affected; in 2010 this region contained an estimated

4 million cases or 12% of all people living with HIV resulting in

approximately 250,000 deaths. Approximately 2.4 million of these cases are in India.

During 2008 in the United States approximately 1.2 million people

aged ≥13 years were living with HIV, resulting in about 17,500 deaths.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in that

year, 236,400 people or 20% of infected Americans were unaware of their

infection. As of 2016 about 675,000 people have died of HIV/AIDS in the US since the beginning of the HIV epidemic. In the United Kingdom as of 2015, there were approximately 101,200 cases which resulted in 594 deaths. In Canada as of 2008, there were about 65,000 cases causing 53 deaths. Between the first recognition of AIDS (in 1981) and 2009, it has led to nearly 30 million deaths. Rates of HIV are lowest in North Africa and the Middle East (0.1% or less), East Asia (0.1%), and Western and Central Europe (0.2%). The worst-affected European countries, in 2009 and 2012 estimates, are Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, Moldova, Portugal and Belarus, in decreasing order of prevalence.

History

Discovery

The first news story on the disease appeared on May 18, 1981, in the gay newspaper New York Native. AIDS was first clinically reported on June 5, 1981, with five cases in the United States.

The initial cases were a cluster of injecting drug users and gay men

with no known cause of impaired immunity who showed symptoms of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), a rare opportunistic infection that was known to occur in people with very compromised immune systems. Soon thereafter, a large number of homosexual men developed a generally rare skin cancer called Kaposi's sarcoma (KS).

Many more cases of PCP and KS emerged, alerting U.S. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and a CDC task force was formed to

monitor the outbreak.

In the early days, the CDC did not have an official name for the

disease, often referring to it by way of diseases associated with it,

such as lymphadenopathy, the disease after which the discoverers of HIV originally named the virus. They also used Kaposi's sarcoma and opportunistic infections, the name by which a task force had been set up in 1981. At one point the CDC referred to it as the "4H disease", as the syndrome seemed to affect heroin users, homosexuals, hemophiliacs, and Haitians. The term GRID, which stood for gay-related immune deficiency, had also been coined. However, after determining that AIDS was not isolated to the gay community, it was realized that the term GRID was misleading, and the term AIDS was introduced at a meeting in July 1982. By September 1982 the CDC started referring to the disease as AIDS.

In 1983, two separate research groups led by Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier

declared that a novel retrovirus may have been infecting people with

AIDS, and published their findings in the same issue of the journal Science. Gallo claimed a virus which his group had isolated from a person with AIDS was strikingly similar in shape to other human T-lymphotropic viruses

(HTLVs) that his group had been the first to isolate. Gallo's group

called their newly isolated virus HTLV-III. At the same time,

Montagnier's group isolated a virus from a person presenting with

swelling of the lymph nodes of the neck and physical weakness,

two characteristic symptoms of AIDS. Contradicting the report from

Gallo's group, Montagnier and his colleagues showed that core proteins

of this virus were immunologically different from those of HTLV-I.

Montagnier's group named their isolated virus lymphadenopathy-associated

virus (LAV). As these two viruses turned out to be the same, in 1986, LAV and HTLV-III were renamed HIV.

Origins

The origin of HIV / AIDS and the circumstances that led to its emergence remain unsolved.

Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are believed to have originated in non-human primates in West-central Africa and were transferred to humans in the early 20th century. HIV-1 appears to have originated in southern Cameroon through the evolution of SIV(cpz), a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) that infects wild chimpanzees (HIV-1 descends from the SIVcpz endemic in the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes). The closest relative of HIV-2 is SIV (smm), a virus of the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys atys), an Old World monkey living in coastal West Africa (from southern Senegal to western Ivory Coast). New World monkeys such as the owl monkey are resistant to HIV-1 infection, possibly because of a genomic fusion of two viral resistance genes.

HIV-1 is thought to have jumped the species barrier on at least three

separate occasions, giving rise to the three groups of the virus, M, N,

and O.

There is evidence that humans who participate in bushmeat activities, either as hunters or as bushmeat vendors, commonly acquire SIV.

However, SIV is a weak virus which is typically suppressed by the human

immune system within weeks of infection. It is thought that several

transmissions of the virus from individual to individual in quick

succession are necessary to allow it enough time to mutate into HIV.

Furthermore, due to its relatively low person-to-person transmission

rate, SIV can only spread throughout the population in the presence of

one or more high-risk transmission channels, which are thought to have

been absent in Africa before the 20th century.

Specific proposed high-risk transmission channels, allowing the

virus to adapt to humans and spread throughout society, depend on the

proposed timing of the animal-to-human crossing. Genetic studies of the

virus suggest that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group

dates back to c. 1910. Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of colonialism

and growth of large colonial African cities, leading to social changes,

including a higher degree of sexual promiscuity, the spread of

prostitution, and the accompanying high frequency of genital ulcer diseases (such as syphilis) in nascent colonial cities.

While transmission rates of HIV during vaginal intercourse are low

under regular circumstances, they are increased manyfold if one of the

partners has a sexually transmitted infection

causing genital ulcers. Early 1900s colonial cities were notable for

their high prevalence of prostitution and genital ulcers, to the degree

that, as of 1928, as many as 45% of female residents of eastern Kinshasa were thought to have been prostitutes, and, as of 1933, around 15% of all residents of the same city had syphilis.

An alternative view holds that unsafe medical practices in Africa

after World War II, such as unsterile reuse of single-use syringes

during mass vaccination, antibiotic and anti-malaria treatment

campaigns, were the initial vector that allowed the virus to adapt to

humans and spread.

The earliest well-documented case of HIV in a human dates back to 1959 in the Congo. The virus may have been present in the U.S. as early as the mid-to-late 1950s, as a sixteen-year-old male named Robert Rayford

presented with symptoms in 1966 and died in 1969. In the 1970s, there

were cases of getting parasites and becoming sick with what was called

"gay bowel disease", but what is now suspected to have been AIDS.

The earliest retrospectively described case of AIDS is believed to have been in Norway beginning in 1966, that of Arvid Noe. In July 1960, in the wake of Congo's independence, the United Nations recruited Francophone experts and technicians from all over the world to assist in filling administrative gaps left by Belgium,

who did not leave behind an African elite to run the country. By 1962,

Haitians made up the second-largest group of well-educated experts (out

of the 48 national groups recruited), that totaled around 4500 in the

country. Dr. Jacques Pépin, a Canadian author of The Origins of AIDS, stipulates that Haiti was one of HIV's entry points to the U.S. and that a Haitian may have carried HIV back across the Atlantic in the 1960s. Although there was known to have been at least one case of AIDS in the U.S. from 1966,

the vast majority of infections occurring outside sub-Saharan Africa

(including the U.S.) can be traced back to a single unknown individual

who became infected with HIV in Haiti and brought the infection to the

U.S. at some time around 1969.

The epidemic rapidly spread among high-risk groups (initially, sexually

promiscuous men who have sex with men). By 1978, the prevalence of

HIV-1 among gay male residents of New York City and San Francisco was estimated at 5%, suggesting that several thousand individuals in the country had been infected.

Society and culture

Stigma

AIDS stigma exists around the world in a variety of ways, including ostracism, rejection, discrimination and avoidance of HIV-infected people; compulsory HIV testing without prior consent or protection of confidentiality; violence against HIV-infected individuals or people who are perceived to be infected with HIV; and the quarantine of HIV-infected individuals.

Stigma-related violence or the fear of violence prevents many people

from seeking HIV testing, returning for their results, or securing

treatment, possibly turning what could be a manageable chronic illness

into a death sentence and perpetuating the spread of HIV.

AIDS stigma has been further divided into the following three categories:

- Instrumental AIDS stigma—a reflection of the fear and apprehension that are likely to be associated with any deadly and transmissible illness.

- Symbolic AIDS stigma—the use of HIV/AIDS to express attitudes toward the social groups or lifestyles perceived to be associated with the disease.

- Courtesy AIDS stigma—stigmatization of people connected to the issue of HIV/AIDS or HIV-positive people.

Often, AIDS stigma is expressed in conjunction with one or more other

stigmas, particularly those associated with homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, prostitution, and intravenous drug use.

In many developed countries, there is an association between AIDS and homosexuality or bisexuality, and this association is correlated with higher levels of sexual prejudice, such as anti-homosexual or anti-bisexual attitudes. There is also a perceived association between AIDS and all male-male sexual behavior, including sex between uninfected men. However, the dominant mode of spread worldwide for HIV remains heterosexual transmission.

In 2003, as part of an overall reform of marriage and population

legislation, it became legal for those diagnosed with AIDS to marry in

China.

In 2013, the U.S. National Library of Medicine developed a traveling exhibition titled Surviving and Thriving: AIDS, Politics, and Culture;

this covered medical research, the U.S. government's response, and

personal stories from people with AIDS, caregivers, and activists.

Economic impact

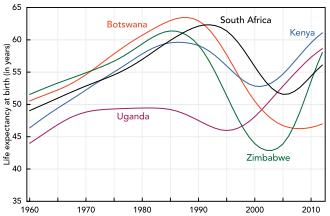

Changes in life expectancy in some African countries, 1960–2012

HIV/AIDS affects the economics of both individuals and countries. The gross domestic product of the most affected countries has decreased due to the lack of human capital.

Without proper nutrition, health care and medicine, large numbers of

people die from AIDS-related complications. Before death they will not

only be unable to work, but will also require significant medical care.

It is estimated that as of 2007 there were 12 million AIDS orphans. Many are cared for by elderly grandparents.

Returning to work after beginning treatment for HIV/AIDS is

difficult, and affected people often work less than the average worker. Unemployment in people with HIV/AIDS also is associated with suicidal ideation, memory problems, and social isolation. Employment increases self-esteem, sense of dignity, confidence, and quality of life

for people with HIV/AIDS. Anti-retroviral treatment may help people

with HIV/AIDS work more, and may increase the chance that a person with

HIV/AIDS will be employed (low-quality evidence).

By affecting mainly young adults, AIDS reduces the taxable population, in turn reducing the resources available for public expenditures

such as education and health services not related to AIDS, resulting in

increasing pressure on the state's finances and slower growth of the

economy. This causes a slower growth of the tax base, an effect that is

reinforced if there are growing expenditures on treating the sick,

training (to replace sick workers), sick pay, and caring for AIDS

orphans. This is especially true if the sharp increase in adult

mortality shifts the responsibility from the family to the government in

caring for these orphans.

At the household level, AIDS causes both loss of income and increased spending on healthcare. A study in Côte d'Ivoire

showed that households having a person with HIV/AIDS spent twice as

much on medical expenses as other households. This additional

expenditure also leaves less income to spend on education and other

personal or family investment.

Religion and AIDS

The topic of religion and AIDS has become highly controversial,

primarily because some religious authorities have publicly declared

their opposition to the use of condoms. The religious approach to prevent the spread of AIDS, according to a report by American health expert Matthew Hanley titled The Catholic Church and the Global AIDS Crisis,

argues that cultural changes are needed, including a re-emphasis on

fidelity within marriage and sexual abstinence outside of it.

Some religious organizations have claimed that prayer can cure

HIV/AIDS. In 2011, the BBC reported that some churches in London were

claiming that prayer would cure AIDS, and the Hackney-based

Centre for the Study of Sexual Health and HIV reported that several

people stopped taking their medication, sometimes on the direct advice

of their pastor, leading to many deaths. The Synagogue Church Of All Nations advertised an "anointing water" to promote God's healing, although the group denies advising people to stop taking medication.

Media portrayal

One of the first high-profile cases of AIDS was the American gay actor Rock Hudson.

He had been diagnosed during 1984, announced that he had had the virus

on July 25, 1985, and died a few months later on October 2, 1985. Another notable British casualty of AIDS that year was Nicholas Eden, a gay politician and son of former prime minister Anthony Eden. On November 24, 1991, the virus claimed the life of British rock star Freddie Mercury, lead singer of the band Queen, who died from an AIDS-related illness having only revealed the diagnosis on the previous day.

One of the first high-profile heterosexual cases of the virus was American tennis player Arthur Ashe.

He was diagnosed as HIV-positive on August 31, 1988, having contracted

the virus from blood transfusions during heart surgery earlier in the

1980s. Further tests within 24 hours of the initial diagnosis revealed

that Ashe had AIDS, but he did not tell the public about his diagnosis

until April 1992. He died as a result on February 6, 1993, aged 49.

Therese Frare's photograph of gay activist David Kirby, as he lay dying from AIDS while surrounded by family, was taken in April 1990. Life

magazine said the photo became the one image "most powerfully

identified with the HIV/AIDS epidemic." The photo was displayed in Life, was the winner of the World Press Photo, and acquired worldwide notoriety after being used in a United Colors of Benetton advertising campaign in 1992.

Many famous artists and AIDS activists such as Larry Kramer, Diamanda Galás and Rosa von Praunheim campaign for AIDS education and the rights of those affected. These artists worked with various media formats.

Criminal transmission

Criminal transmission of HIV is the intentional or reckless infection of a person with the human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV). Some countries or jurisdictions, including some areas of the

United States, have laws that criminalize HIV transmission or exposure. Others may charge the accused under laws enacted before the HIV pandemic.

In 1996, Ugandan-born Canadian Johnson Aziga

was diagnosed with HIV; he subsequently had unprotected sex with eleven

women without disclosing his diagnosis. By 2003, seven had contracted

HIV; two died from complications related to AIDS. Aziga was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Misconceptions

There are many misconceptions about HIV and AIDS. Three misconceptions are that AIDS can spread through casual contact, that sexual intercourse with a virgin will cure AIDS, and that HIV can infect only gay men and drug users.

In 2014, some among the British public wrongly thought one could get

HIV from kissing (16%), sharing a glass (5%), spitting (16%), a public

toilet seat (4%), and coughing or sneezing (5%).

Other misconceptions are that any act of anal intercourse between two

uninfected gay men can lead to HIV infection, and that open discussion

of HIV and homosexuality in schools will lead to increased rates of

AIDS.

A small group of individuals continue to dispute the connection between HIV and AIDS, the existence of HIV itself, or the validity of HIV testing and treatment methods. These claims, known as AIDS denialism, have been examined and rejected by the scientific community. However, they have had a significant political impact, particularly in South Africa,

where the government's official embrace of AIDS denialism (1999–2005)

was responsible for its ineffective response to that country's AIDS

epidemic, and has been blamed for hundreds of thousands of avoidable

deaths and HIV infections.

Several discredited conspiracy theories have held that HIV was created by scientists, either inadvertently or deliberately. Operation INFEKTION was a worldwide Soviet active measures

operation to spread the claim that the United States had created

HIV/AIDS. Surveys show that a significant number of people believed—and

continue to believe—in such claims.

Research

HIV/AIDS research includes all medical research

which attempts to prevent, treat, or cure HIV/AIDS, along with

fundamental research about the nature of HIV as an infectious agent, and

about AIDS as the disease caused by HIV.

Many governments and research institutions participate in HIV/AIDS research. This research includes behavioral health interventions such as sex education, and drug development, such as research into microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV vaccines, and antiretroviral drugs. Other medical research areas include the topics of pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis, and circumcision and HIV.

Public health officials, researchers, and programs can gain a more

comprehensive picture of the barriers they face, and the efficacy of

current approaches to HIV treatment and prevention, by tracking standard

HIV indicators. Use of common indicators is an increasing focus of development organizations and researchers.