| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɜːrtrəˌliːn/ |

| Trade names | Zoloft, Lustral, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697048 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Addiction liability | None |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Officially SSRI) With Weak DAT Inhibition |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 44% |

| Protein binding | 98.5% |

| Metabolism | Liver (N-demethylation mainly by CYP2B6) |

| Metabolites | norsertraline |

| Elimination half-life | ~23–26 h (66 h [less-active metabolite, norsertraline]) |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H17Cl2N |

| Molar mass | 306.23 g·mol−1 |

Sertraline, sold under the brand name Zoloft among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. The efficacy of sertraline for depression is similar to that of other antidepressants, and the differences are mostly confined to side effects. Sertraline is better tolerated than the older tricyclic antidepressants, and it may work better than fluoxetine for some subtypes of depression. Sertraline is effective for panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). However, for OCD, cognitive behavioral therapy, particularly in combination with sertraline, is a better treatment. Although approved for post-traumatic stress disorder, sertraline leads to only modest improvement in this condition. Sertraline also alleviates the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and can be used in sub-therapeutic doses or intermittently for its treatment.

Sertraline shares the common side effects and contraindications of other SSRIs, with high rates of nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, and sexual side effects, but it appears not to lead to much weight gain, and its effects on cognitive performance are mild. Similar to other antidepressants, the use of sertraline for depression may be associated with a higher rate of suicidal thoughts and behavior in people under the age of 25. It should not be used together with MAO inhibitor medication: this combination causes serotonin syndrome. Sertraline taken during pregnancy is associated with a significant increase in congenital heart defects in newborns.

Sertraline was invented and developed by scientists at Pfizer and approved for medical use in the United States in 1991. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. In 2016, sertraline was the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medication in the United States and in 2019, it was the twelfth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with over 37 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

Sertraline has been approved for major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder (SAD). Sertraline is not approved for use in children except for those with OCD.

Depression

Multiple controlled clinical trials established efficacy of sertraline for the treatment of depression. Sertraline is also an effective antidepressant in the routine clinical practice. Continued treatment with sertraline prevents both a relapse of the current depressive episode and future episodes (recurrence of depression).

In several double-blind studies, sertraline was consistently more effective than placebo for dysthymia, a more chronic variety of depression, and comparable to imipramine in that respect. Sertraline also improves the depression of dysthymic patients to a greater degree than psychotherapy.

Sertraline provides no benefit to children and adolescents with depression.

Comparison with other antidepressants

In general, sertraline efficacy is similar to that of other antidepressants. For example, a meta-analysis of 12 new-generation antidepressants showed that sertraline and escitalopram are the best in terms of efficacy and acceptability in the acute-phase treatment of adults with depression. Comparative clinical trials demonstrated that sertraline is similar in efficacy against depression to moclobemide, nefazodone, escitalopram, bupropion, citalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, venlafaxine and mirtazapine. Sertraline may be more efficacious for the treatment of depression in the acute phase (first 4 weeks) than fluoxetine.

There are differences between sertraline and some other antidepressants in their efficacy in the treatment of different subtypes of depression and in their adverse effects. For severe depression, sertraline is as good as clomipramine but is better tolerated. Sertraline appears to work better in melancholic depression than fluoxetine, paroxetine, and mianserin and is similar to the tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline and clomipramine. In the treatment of depression accompanied by OCD, sertraline performs significantly better than desipramine on the measures of both OCD and depression. Sertraline is equivalent to imipramine for the treatment of depression with co-morbid panic disorder, but it is better tolerated. Compared with amitriptyline, sertraline offered a greater overall improvement in quality of life of depressed patients.

Depression in elderly

Sertraline used for the treatment of depression in elderly (older than 60) patients is superior to placebo and comparable to another SSRI fluoxetine, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) amitriptyline, nortriptyline and imipramine. Sertraline has much lower rates of adverse effects than these TCAs, with the exception of nausea, which occurs more frequently with sertraline. In addition, sertraline appears to be more effective than fluoxetine or nortriptyline in the older-than-70 subgroup. Accordingly, a meta-analysis of antidepressants in older adults found that sertraline, paroxetine and duloxetine were better than placebo. On the other hand, in a 2003 trial the effect size was modest, and there was no improvement in quality of life as compared to placebo. With depression in dementia, there is no benefit of sertraline treatment compared to either placebo or mirtazapine.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Sertraline is effective for the treatment of OCD in adults and children. It was better tolerated and, based on intention-to-treat analysis, performed better than the gold standard of OCD treatment clomipramine. Continuing sertraline treatment helps prevent relapses of OCD with long-term data supporting its use for up to 24 months. It is generally accepted that the sertraline dosages necessary for the effective treatment of OCD are higher than the usual dosage for depression. The onset of action is also slower for OCD than for depression. The treatment recommendation is to start treatment with a half of maximal recommended dose for at least two months. After that, the dose can be raised to the maximal recommended in the cases of unsatisfactory response.

Cognitive behavioral therapy alone was superior to sertraline in both adults and children; however, the best results were achieved using a combination of these treatments.

Panic disorder

Sertraline is superior to placebo for the treatment of panic disorder. The response rate was independent of the dose. In addition to decreasing the frequency of panic attacks by about 80% (vs. 45% for placebo) and decreasing general anxiety, sertraline resulted in improvement of quality of life on most parameters. The patients rated as "improved" on sertraline reported better quality of life than the ones who "improved" on placebo. The authors of the study argued that the improvement achieved with sertraline is different and of a better quality than the improvement achieved with placebo. Sertraline is equally effective for men and women, and for patients with or without agoraphobia. Previous unsuccessful treatment with benzodiazepines does not diminish its efficacy. However, the response rate was lower for the patients with more severe panic. Starting treatment simultaneously with sertraline and clonazepam, with subsequent gradual discontinuation of clonazepam, may accelerate the response.

Double-blind comparative studies found sertraline to have the same effect on panic disorder as paroxetine or imipramine. While imprecise, comparison of the results of trials of sertraline with separate trials of other anti-panic agents (clomipramine, imipramine, clonazepam, alprazolam, and fluvoxamine) indicates approximate equivalence of these medications.

Other anxiety disorders

Sertraline has been successfully used for the treatment of social anxiety disorder. All three major domains of the disorder (fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms) respond to sertraline. Maintenance treatment, after the response is achieved, prevents the return of the symptoms. The improvement is greater among the patients with later, adult onset of the disorder. In a comparison trial, sertraline was superior to exposure therapy, but patients treated with the psychological intervention continued to improve during a year-long follow-up, while those treated with sertraline deteriorated after treatment termination. The combination of sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy appears to be more effective in children and young people than either treatment alone.

Sertraline has not been approved for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder; however, several guidelines recommend it as a first-line medication referring to good quality controlled clinical trials.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Sertraline is effective in alleviating the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a severe form of premenstrual syndrome. Significant improvement was observed in 50–60% of cases treated with sertraline vs. 20–30% of cases on placebo. The improvement began during the first week of treatment, and in addition to mood, irritability, and anxiety, improvement was reflected in better family functioning, social activity and general quality of life. Work functioning and physical symptoms, such as swelling, bloating and breast tenderness, were less responsive to sertraline. Taking sertraline only during the luteal phase, that is, the 12–14 days before menses, was shown to work as well as continuous treatment. Continuous treatment with sub-therapeutic doses of sertraline (25 mg vs. usual 50–100 mg) is also effective.

Other indications

Sertraline is approved for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). National Institute of Clinical Excellence recommends it for patients who prefer drug treatment to a psychological one. Other guidelines also suggest sertraline as a first-line option for pharmacological therapy. When necessary, long-term pharmacotherapy can be beneficial. There are both negative and positive clinical trial results for sertraline, which may be explained by the types of psychological traumas, symptoms, and comorbidities included in the various studies. Positive results were obtained in trials that included predominantly women (75%) with a majority (60%) having physical or sexual assault as the traumatic event. Contrary to the above suggestions, a meta-analysis of sertraline clinical trials for PTSD found it to be not significantly better than placebo. Another meta-analysis relegated sertraline to the second line, proposing trauma focused psychotherapy as a first-line intervention. The authors noted that Pfizer had declined to submit the results of a negative trial for the inclusion into the meta-analysis making the results unreliable.

Sertraline when taken daily can be useful for the treatment of premature ejaculation. A disadvantage of sertraline is that it requires continuous daily treatment to delay ejaculation significantly.

A 2019 systematic review suggested that sertraline may be a good way to control anger, irritability and hostility in depressed patients and patients with other comorbidities.

Contraindications

Sertraline is contraindicated in individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors or the antipsychotic pimozide. Sertraline concentrate contains alcohol and is therefore contraindicated with disulfiram. The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution". Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.

Side effects

Nausea, ejaculation failure, insomnia, diarrhea, dry mouth, somnolence, dizziness, tremor, and decreased libido are the common adverse effects associated with sertraline with the greatest difference from placebo. Those that most often resulted in interruption of the treatment are nausea, diarrhea and insomnia. The incidence of diarrhea is higher with sertraline—especially when prescribed at higher doses—in comparison with other SSRIs.

Over more than six months of sertraline therapy for depression, people showed a nonsignificant weight increase of 0.1%. Similarly, a 30-month-long treatment with sertraline for OCD resulted in a mean weight gain of 1.5% (1 kg). Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the average weight gain was lower for fluoxetine (1%) but higher for citalopram, fluvoxamine and paroxetine (2.5%). Of the sertraline group, 4.5% gained a large amount of weight (defined as more than 7% gain). This result compares favorably with placebo, where, according to the literature, 3–6% of patients gained more than 7% of their initial weight. The large weight gain was observed only among female members of the sertraline group; the significance of this finding is unclear because of the small size of the group.

Over a two-week treatment of healthy volunteers, sertraline slightly improved verbal fluency but did not affect word learning, short-term memory, vigilance, flicker fusion time, choice reaction time, memory span, or psychomotor coordination. In spite of lower subjective rating, that is, feeling that they performed worse, no clinically relevant differences were observed in the objective cognitive performance in a group of people treated for depression with sertraline for 1.5 years as compared to healthy controls. In children and adolescents taking sertraline for six weeks for anxiety disorders, 18 out of 20 measures of memory, attention and alertness stayed unchanged. Divided attention was improved and verbal memory under interference conditions decreased marginally. Because of the large number of measures taken, it is possible that these changes were still due to chance. The unique effect of sertraline on dopaminergic neurotransmission may be related to these effects on cognition and vigilance.

Sertraline has a low level of exposure of an infant through the breast milk and is recommended as the preferred option for the antidepressant therapy of breast-feeding mothers. There is 29-42% increase in congenital heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed sertraline during pregnancy, with sertraline use in the first trimester associated with 2.7-fold increase in septal heart defects.

Abrupt interruption of sertraline treatment may result in withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome. Dizziness, insomnia, anxiety, agitation, and irritability are its common symptoms. It typically occurs within a few days from drug discontinuation and lasts a few weeks. The withdrawal symptoms for sertraline are less severe and frequent than for paroxetine, and more frequent than for fluoxetine. In most cases symptoms are mild, short-lived, and resolve without treatment. More severe cases are often successfully treated by temporary reintroduction of the drug with a slower tapering off rate.

Sertraline and SSRI antidepressants in general may be associated with bruxism and other movement disorders. Sertraline appears to be associated with microscopic colitis, a rare condition of unknown etiology.

Sexual

Like other SSRIs, sertraline is associated with sexual side effects, including sexual arousal disorder, erectile dysfunction and difficulty achieving orgasm. While nefazodone and bupropion do not have negative effects on sexual functioning, 67% of men on sertraline experienced ejaculation difficulties versus 18% before the treatment. Sexual arousal disorder, defined as "inadequate lubrication and swelling for women and erectile difficulties for men", occurred in 12% of people on sertraline as compared with 1% of patients on placebo. The mood improvement resulting from the treatment with sertraline sometimes counteracted these side effects, so that sexual desire and overall satisfaction with sex stayed the same as before the sertraline treatment. However, under the action of placebo the desire and satisfaction slightly improved. Some people continue experiencing sexual side effects after they stop taking SSRIs.

Suicide

The FDA requires all antidepressants, including sertraline, to carry a boxed warning stating that antidepressants increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25 years. This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts that found a 100% increase of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and adolescents, and a 50% increase - in the 18 – 24 age group.

Suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare. For the above analysis, the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications in order to obtain statistically significant results. Considered separately, sertraline use in adults decreased the odds of suicidal behavior with a marginal statistical significance by 37% or 50% depending on the statistical technique used. The authors of the FDA analysis note that "given the large number of comparisons made in this review, chance is a very plausible explanation for this difference". The more complete data submitted later by the sertraline manufacturer Pfizer indicated increased suicidal behavior. Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase of odds of suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the patients on sertraline as compared to the ones on placebo.

Overdose

Acute overdosage is often manifested by emesis, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia and seizures. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of sertraline and norsertraline, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. As with most other SSRIs its toxicity in overdose is considered relatively low.

Interactions

Sertraline is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 in vitro. Accordingly, in human trials it caused increased blood levels of CYP2D6 substrates such as metoprolol, dextromethorphan, desipramine, imipramine and nortriptyline, as well as the CYP3A4/CYP2D6 substrate haloperidol. This effect is dose-dependent; for example, co-administration with 50 mg of sertraline resulted in 20% greater exposure to desipramine, while 150 mg of sertraline led to a 70% increase. In a placebo-controlled study, the concomitant administration of sertraline and methadone caused a 40% increase in blood levels of the latter, which is primarily metabolized by CYP2B6.

Sertraline had a slight inhibitory effect on the metabolism of diazepam, tolbutamide and warfarin, which are CYP2C9 or CYP2C19 substrates; the clinical relevance of this effect was unclear. As expected from in vitro data, sertraline did not alter the human metabolism of the CYP3A4 substrates erythromycin, alprazolam, carbamazepine, clonazepam, and terfenadine; neither did it affect metabolism of the CYP1A2 substrate clozapine.

Sertraline had no effect on the actions of digoxin and atenolol, which are not metabolized in the liver. Case reports suggest that taking sertraline with phenytoin or zolpidem may induce sertraline metabolism and decrease its efficacy, and that taking sertraline with lamotrigine may increase the blood level of lamotrigine, possibly by inhibition of glucuronidation.

CYP2C19 inhibitor esomeprazole increased sertraline concentrations in blood plasma by approximately 40%.

Clinical reports indicate that interaction between sertraline and the MAOIs isocarboxazid and tranylcypromine may cause serotonin syndrome. In a placebo-controlled study in which sertraline was co-administered with lithium, 35% of the subjects experienced tremors, while none of those taking placebo did.

Sertraline may interact with grapefruit juice - see Grapefruit–drug interactions.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). By binding serotonin transporter (SERT) it inhibits neuronal reuptake of serotonin and potentiates serotonergic activity in the central nervous system. It does not significantly affect norepinephrine transporter (NET), serotonin, dopamine, adrenergic, histamine, acetylcholine, GABA or benzodiazepine receptors.

Sertraline also shows relatively high activity as an inhibitor of the dopamine transporter (DAT) and antagonist of the sigma σ1 receptor (but not the σ2 receptor). However, sertraline affinity for its main target (SERT) is much greater than its affinity for σ1 receptor and DAT. Although there could be a role for the σ1 receptor in the pharmacology of sertraline, the significance of this receptor in its actions is unclear. Similarly, the clinical relevance of sertraline's blockade of the dopamine transporter is uncertain.

Pharmacokinetics

Sertraline is absorbed slowly when taken orally, achieving its maximal concentration in the plasma 4 to 6 hours after ingestion. In the blood, it is 98.5% bound to plasma proteins. Its half-life in the body is 13–45 hours and, on average, is about 1.5 times longer in women (32 hours) than in men (22 hours), leading to a 1.5-times-higher exposure in women. According to in vitro studies, sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome 450 isoforms; however, it appears that in the human body CYP2C19 plays the most important role, followed by CYP2B6. Poor CYP2C19 metabolizers have 2.7-fold higher levels of sertraline, and intermediate metabolizers - 1.4-fold higher levels, than normal (extensive) metabolizers. In contrast, poor CYP2B6 metabolizers have 1.6-fold higher levels of sertraline and intermediate metabolizers - 1.2-fold higher levels.

The major metabolite of sertraline, desmethylsertraline, is about 50 times weaker as a serotonin transporter inhibitor than sertraline and its clinical effect is negligible.[106] Sertraline can be deaminated in vitro by monoamine oxidases; however, this metabolic pathway has never been studied in vivo.

History

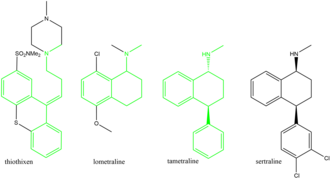

The history of sertraline dates back to the early 1970s, when Pfizer chemist Reinhard Sarges invented a novel series of psychoactive compounds, including lometraline, based on the structures of the neuroleptics thiothixene and pinoxepin. Further work on these compounds led to tametraline, a norepinephrine and weaker dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Development of tametraline was soon stopped because of undesired stimulant effects observed in animals. A few years later, in 1977, pharmacologist Kenneth Koe, after comparing the structural features of a variety of reuptake inhibitors, became interested in the tametraline series. He asked another Pfizer chemist, Willard Welch, to synthesize some previously unexplored tametraline derivatives. Welch generated a number of potent norepinephrine and triple reuptake inhibitors, but to the surprise of the scientists, one representative of the generally inactive cis-analogs was a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Welch then prepared stereoisomers of this compound, which were tested in vivo by animal behavioral scientist Albert Weissman. The most potent and selective (+)-isomer was taken into further development and eventually named sertraline. Weissman and Koe recalled that the group did not set up to produce an antidepressant of the SSRI type—in that sense their inquiry was not "very goal driven", and the discovery of the sertraline molecule was serendipitous. According to Welch, they worked outside the mainstream at Pfizer, and even "did not have a formal project team". The group had to overcome initial bureaucratic reluctance to pursue sertraline development, as Pfizer was considering licensing an antidepressant candidate from another company.

Sertraline was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991 based on the recommendation of the Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee; it had already become available in the United Kingdom the previous year. The FDA committee achieved a consensus that sertraline was safe and effective for the treatment of major depression. During the discussion, Paul Leber, the director of the FDA Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products, noted that granting approval was a "tough decision", since the treatment effect on outpatients with depression had been "modest to minimal". Other experts emphasized that the drug's effect on inpatients had not differed from placebo and criticized poor design of the clinical trials by Pfizer. For example, 40% of participants dropped out of the trials, significantly decreasing their validity.

Until 2002, sertraline was only approved for use in adults ages 18 and over; that year, it was approved by the FDA for use in treating children aged 6 or older with severe OCD. In 2003, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a guidance that, apart from fluoxetine (Prozac), SSRIs are not suitable for the treatment of depression in patients under 18. However, sertraline can still be used in the UK for the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents. In 2005, the FDA added a boxed warning concerning pediatric suicidal behavior to all antidepressants, including sertraline. In 2007, labeling was again changed to add a warning regarding suicidal behavior in young adults ages 18 to 24.

Society and culture

Generic availability

The US patent for Zoloft expired in 2006, and sertraline is available in generic form and is marketed under many brand names worldwide.

In May 2020, the FDA placed Zoloft on the list of drugs currently facing a shortage.