Mutually assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy in which a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by two or more opposing sides would cause the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender (see pre-emptive nuclear strike and second strike). It is based on the theory of deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

The term "mutual assured destruction", commonly abbreviated "MAD", was coined by Donald Brennan, a strategist working in Herman Kahn's Hudson Institute in 1962. However, Brennan came up with this acronym ironically, to argue that holding weapons capable of destroying society was irrational.

Theory

Under MAD, each side has enough nuclear weaponry to destroy the other side. Either side, if attacked for any reason by the other, would retaliate with equal or greater force. The expected result is an immediate, irreversible escalation of hostilities resulting in both combatants' mutual, total, and assured destruction. The doctrine requires that neither side construct shelters on a massive scale. If one side constructed a similar system of shelters, it would violate the MAD doctrine and destabilize the situation, because it would have less to fear from a second strike. The same principle is invoked against missile defense.

The doctrine further assumes that neither side will dare to launch a first strike because the other side would launch on warning (also called fail-deadly) or with surviving forces (a second strike), resulting in unacceptable losses for both parties. The payoff of the MAD doctrine was and still is expected to be a tense but stable global peace. However, many have argued that mutually assured destruction is unable to deter unconventional war that could later escalate. Emerging domains of cyber-espionage, proxy-state conflict, and high-speed missiles threaten to circumvent MAD as a deterrent strategy.

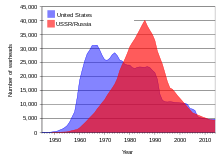

The primary application of this doctrine started during the Cold War (1940s to 1991), in which MAD was seen as helping to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union while they engaged in smaller proxy wars around the world. It was also responsible for the arms race, as both nations struggled to keep nuclear parity, or at least retain second-strike capability. Although the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, the MAD doctrine continues to be applied.

Proponents of MAD as part of the US and USSR strategic doctrine believed that nuclear war could best be prevented if neither side could expect to survive a full-scale nuclear exchange as a functioning state. Since the credibility of the threat is critical to such assurance, each side had to invest substantial capital in their nuclear arsenals even if they were not intended for use. In addition, neither side could be expected or allowed to adequately defend itself against the other's nuclear missiles. This led both to the hardening and diversification of nuclear delivery systems (such as nuclear missile silos, ballistic missile submarines, and nuclear bombers kept at fail-safe points) and to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

This MAD scenario is often referred to as nuclear deterrence. The term "deterrence" is now used in this context; originally, its use was limited to legal terminology.

Theory of Mutual Assured Destruction

When nuclear warfare between the United States and Soviet Union started to become a reality, theorists began to think that mutual assured destruction would be sufficient to deter the other side from launching a nuclear weapon. Kenneth Waltz, an American scientist, believed that nuclear forces were in fact useful, but even more useful in the fact that they deterred other nuclear threats from using them, based on mutually assured destruction. The theory of mutually assured destruction being a safe way to deter continued even farther with the thought that nuclear weapons intended on being used for the winning of a war, were unpractical, and even considered too dangerous and risky. Even with the Cold War ending in 1991, about 30 years ago, deterrence from mutually assured destruction is still said to be the safest course to avoid nuclear warfare.

History

Pre-1945

The concept of MAD had been discussed in the literature for nearly a century before the invention of nuclear weapons. One of the earliest references comes from the English author Wilkie Collins, writing at the time of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870: "I begin to believe in only one civilizing influence—the discovery one of these days of a destructive agent so terrible that War shall mean annihilation and men's fears will force them to keep the peace." The concept was also described in 1863 by Jules Verne in his novel Paris in the Twentieth Century, though it was not published until 1994. The book is set in 1960 and describes "the engines of war", which have become so efficient that war is inconceivable and all countries are at a perpetual stalemate.

MAD has been invoked by more than one weapons inventor. For example, Richard Jordan Gatling patented his namesake Gatling gun in 1862 with the partial intention of illustrating the futility of war. Likewise, after his 1867 invention of dynamite, Alfred Nobel stated that "the day when two army corps can annihilate each other in one second, all civilized nations, it is to be hoped, will recoil from war and discharge their troops." In 1937, Nikola Tesla published The Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through the Natural Media, a treatise concerning charged particle beam weapons. Tesla described his device as a "superweapon that would put an end to all war."

The March 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum, the earliest technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon, anticipated deterrence as the principal means of combating an enemy with nuclear weapons.

Early Cold War

In August 1945, the United States became the first nuclear power after the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Four years later, on August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its own nuclear device. At the time, both sides lacked the means to effectively use nuclear devices against each other. However, with the development of aircraft like the American Convair B-36 and the Soviet Tupolev Tu-95, both sides were gaining a greater ability to deliver nuclear weapons into the interior of the opposing country. The official policy of the United States became one of "massive retaliation", as coined by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, which called for massive attack against the Soviet Union if they were to invade Europe, regardless of whether it was a conventional or a nuclear attack.

By the time of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, both the United States and the Soviet Union had developed the capability of launching a nuclear-tipped missile from a submerged submarine, which completed the "third leg" of the nuclear triad weapons strategy necessary to fully implement the MAD doctrine. Having a three-branched nuclear capability eliminated the possibility that an enemy could destroy all of a nation's nuclear forces in a first-strike attack; this, in turn, ensured the credible threat of a devastating retaliatory strike against the aggressor, increasing a nation's nuclear deterrence.

Campbell Craig and Sergey Radchenko argue that Nikita Khrushchev (Soviet leader 1953 to 1964) decided that policies that facilitated nuclear war were too dangerous to the Soviet Union. His approach did not greatly change his foreign policy or military doctrine but is apparent in his determination to choose options that minimized the risk of war.

How Mutually Assured Destruction was Seen During the Cold War

As the United States continued to build and place their nuclear weapons during the Cold War, it became clear to United States officials that there was no defense against a nuclear attack from the Soviet Union. This led to the dismantling of defense systems, both civil and antiballistic. The United States began to discontinue the deployment of nuclear forces in the 1950s, starting in Europe and the Middle East. By the 1960s and 1970s, the United States began to withdraw these nuclear forces.

The United States withdrawing nuclear forces from Europe and the Middle East actually had a deference affect on the Soviet Union, showing that the United States knew using nuclear weapons would mean their own demise as well due to mutually assured destruction. "The Soviet Union inevitably would recognize it and see the pointlessness of building ever-larger nuclear forces, not just for strategic operations but also for tactical and theater operations."

Paranoia in the United States Concerning Mutually Assured Destruction During the Cold War

While many United States officials recognized that there were was no legitimate way to counter Soviet Union nuclear weapons except to deter, there were those in power in the United States that were not satisfied with just the ability to deter to keep the United States safe. Perhaps the most influential and important of these officials was the United States Navy, who did not want to leave the nation's existence in the hands of "logic", specifically the Soviet Union's leadership and mutual hostage taking between the two super powers.

In the 1960s, the United States Navy looked to counter Soviet Union nuclear weapons by covertly pursuing "anti-submarine warfare". This was a massive success for the United States Navy, as they "achieved operational dominance over Soviet submarines," starting in the 1960s, and continued this dominance throughout the 1970s and 1980s to try and keep Soviet nuclear weapons out of open waters. This constant attack on Soviet submarines put lots of pressure on the Soviet Union. In fact, when Soviet submarines would fall back to Soviet waters, the United States would follow and continue their attacks; constantly putting Soviet submarines at risk.

Strategic Air Command

Beginning in 1955, the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) kept one-third of its bombers on alert, with crews ready to take off within fifteen minutes and fly to designated targets inside the Soviet Union and destroy them with nuclear bombs in the event of a Soviet first-strike attack on the United States. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy increased funding for this program and raised the commitment to 50 percent of SAC aircraft.

During periods of increased tension in the early 1960s, SAC kept part of its B-52 fleet airborne at all times, to allow an extremely fast retaliatory strike against the Soviet Union in the event of a surprise attack on the United States. This program continued until 1969. Between 1954 and 1992, bomber wings had approximately one-third of their assigned aircraft on quick reaction ground alert and were able to take off within a few minutes. SAC also maintained the National Emergency Airborne Command Post (NEACP, pronounced "kneecap"), also known as "Looking Glass", which consisted of several EC-135s, one of which was airborne at all times from 1961 through 1990. During the Cuban Missile Crisis the bombers were dispersed to several different airfields, and also were sometimes airborne. For example, some were sent to Wright Patterson, which normally did not have B-52s.

During the height of the tensions between the US and the USSR in the 1960s, two popular films were made dealing with what could go terribly wrong with the policy of keeping nuclear-bomb-carrying airplanes at the ready: Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Fail Safe (1964).

Retaliation capability (second strike)

The strategy of MAD was fully declared in the early 1960s, primarily by United States Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. In McNamara's formulation, there was the very real danger that a nation with nuclear weapons could attempt to eliminate another nation's retaliatory forces with a surprise, devastating the first strike and theoretically "win" a nuclear war relatively unharmed. The true second-strike capability could be achieved only when a nation had a guaranteed ability to fully retaliate after a first-strike attack.

The United States had achieved an early form of second-strike capability by fielding continual patrols of strategic nuclear bombers, with a large number of planes always in the air, on their way to or from fail-safe points close to the borders of the Soviet Union. This meant the United States could still retaliate, even after a devastating first-strike attack. The tactic was expensive and problematic because of the high cost of keeping enough planes in the air at all times and the possibility they would be shot down by Soviet anti-aircraft missiles before reaching their targets. In addition, as the idea of a missile gap existing between the US and the Soviet Union developed, there was increasing priority being given to ICBMs over bombers.

It was only with the advent of ballistic missile submarines, starting with the George Washington class in 1959, that a genuine survivable nuclear force became possible and a retaliatory second strike capability guaranteed.

The deployment of fleets of ballistic missile submarines established a guaranteed second-strike capability because of their stealth and by the number fielded by each Cold War adversary—it was highly unlikely that all of them could be targeted and preemptively destroyed (in contrast to, for example, a missile silo with a fixed location that could be targeted during a first strike). Given their long-range, high survivability and ability to carry many medium- and long-range nuclear missiles, submarines were credible and effective means for full-scale retaliation even after a massive first strike.

This deterrence strategy and the program have continued into the 21st century, with nuclear submarines carrying Trident II ballistic missiles as one leg of the US strategic nuclear deterrent and as the sole deterrent of the United Kingdom. The other elements of the US deterrent are intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) on alert in the continental United States, and nuclear-capable bombers. Ballistic missile submarines are also operated by the navies of China, France, India, and Russia.

The US Department of Defense anticipates a continued need for a sea-based strategic nuclear force. The first of the current Ohio-class SSBNs are expected to be retired by 2029, meaning that a replacement platform must already be seaworthy by that time. A replacement may cost over $4 billion per unit compared to the USS Ohio's $2 billion. The USN's follow-on class of SSBN will be the Columbia class, scheduled to begin construction in 2021 and enter service in 2031.

ABMs threaten MAD

In the 1960s both the Soviet Union (A-35 anti-ballistic missile system) and the United States (LIM-49 Nike Zeus) developed anti-ballistic missile systems. Had such systems been able to effectively defend against a retaliatory second strike, MAD would have been undermined. However, multiple scientific studies showed technological and logistical problems in these systems, including the inability to distinguish between real and decoy weapons.

MIRVs

MIRVs as counter against ABM

The multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) was another weapons system designed specifically to aid with the MAD nuclear deterrence doctrine. With a MIRV payload, one ICBM could hold many separate warheads. MIRVs were first created by the United States in order to counterbalance the Soviet A-35 anti-ballistic missile systems around Moscow. Since each defensive missile could be counted on to destroy only one offensive missile, making each offensive missile have, for example, three warheads (as with early MIRV systems) meant that three times as many defensive missiles were needed for each offensive missile. This made defending against missile attacks more costly and difficult. One of the largest US MIRVed missiles, the LGM-118A Peacekeeper, could hold up to 10 warheads, each with a yield of around 300 kilotons of TNT (1.3 PJ)—all together, an explosive payload equivalent to 230 Hiroshima-type bombs. The multiple warheads made defense untenable with the available technology, leaving the threat of retaliatory attack as the only viable defensive option. MIRVed land-based ICBMs tend to put a premium on striking first. The START II agreement was proposed to ban this type of weapon, but never entered into force.

In the event of a Soviet conventional attack on Western Europe, NATO planned to use tactical nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union countered this threat by issuing a statement that any use of nuclear weapons (tactical or otherwise) against Soviet forces would be grounds for a full-scale Soviet retaliatory strike (massive retaliation). Thus it was generally assumed that any combat in Europe would end with apocalyptic conclusions.

Land-based MIRVed ICBMs threaten MAD

MIRVed land-based ICBMs are generally considered suitable for a first strike (inherently counterforce) or a counterforce second strike, due to:

- Their high accuracy (low circular error probable), compared to submarine-launched ballistic missiles which used to be less accurate, and more prone to defects;

- Their fast response time, compared to bombers which are considered too slow;

- Their ability to carry multiple MIRV warheads at once, useful for destroying a whole missile field or several cities with one missile.

Unlike a decapitation strike or a countervalue strike, a counterforce strike might result in a potentially more constrained retaliation. Though the Minuteman III of the mid-1960s was MIRVed with three warheads, heavily MIRVed vehicles threatened to upset the balance; these included the SS-18 Satan which was deployed in 1976, and was considered to threaten Minuteman III silos, which led some neoconservatives to conclude a Soviet first strike was being prepared for. This led to the development of the aforementioned Pershing II, the Trident I and Trident II, as well as the MX missile, and the B-1 Lancer.

MIRVed land-based ICBMs are considered destabilizing because they tend to put a premium on striking first. When a missile is MIRVed, it is able to carry many warheads (up to eight in existing US missiles, limited by New START, though Trident II is capable of carrying up to 12) and deliver them to separate targets. If it is assumed that each side has 100 missiles, with five warheads each, and further that each side has a 95 percent chance of neutralizing the opponent's missiles in their silos by firing two warheads at each silo, then the attacking side can reduce the enemy ICBM force from 100 missiles to about five by firing 40 missiles with 200 warheads, and keeping the rest of 60 missiles in reserve. As such, this type of weapon was intended to be banned under the START II agreement; however, the START II agreement was never brought into force, and neither Russia nor the United States ratified the agreement.

Late Cold War

The original US MAD doctrine was modified on July 25, 1980, with US President Jimmy Carter's adoption of countervailing strategy with Presidential Directive 59. According to its architect, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, "countervailing strategy" stressed that the planned response to a Soviet attack was no longer to bomb Soviet population centers and cities primarily, but first to kill the Soviet leadership, then attack military targets, in the hope of a Soviet surrender before total destruction of the Soviet Union (and the United States). This modified version of MAD was seen as a winnable nuclear war, while still maintaining the possibility of assured destruction for at least one party. This policy was further developed by the Reagan administration with the announcement of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI, nicknamed "Star Wars"), the goal of which was to develop space-based technology to destroy Soviet missiles before they reached the United States.

SDI was criticized by both the Soviets and many of America's allies (including Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher) because, were it ever operational and effective, it would have undermined the "assured destruction" required for MAD. If the United States had a guarantee against Soviet nuclear attacks, its critics argued, it would have first-strike capability, which would have been a politically and militarily destabilizing position. Critics further argued that it could trigger a new arms race, this time to develop countermeasures for SDI. Despite its promise of nuclear safety, SDI was described by many of its critics (including Soviet nuclear physicist and later peace activist Andrei Sakharov) as being even more dangerous than MAD because of these political implications. Supporters also argued that SDI could trigger a new arms race, forcing the USSR to spend an increasing proportion of GDP on defense—something which has been claimed to have been an indirect cause of the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev himself in 1983 announced that “the continuation of the S.D.I. program will sweep the world into a new stage of the arms race and would destabilize the strategic situation.”

Proponents of ballistic missile defense (BMD) argue that MAD is exceptionally dangerous in that it essentially offers a single course of action in the event of a nuclear attack: full retaliatory response. The fact that nuclear proliferation has led to an increase in the number of nations in the "nuclear club", including nations of questionable stability (e.g. North Korea), and that a nuclear nation might be hijacked by a despot or other person or persons who might use nuclear weapons without a sane regard for the consequences, presents a strong case for proponents of BMD who seek a policy which both protect against attack, but also does not require an escalation into what might become global nuclear war. Russia continues to have a strong public distaste for Western BMD initiatives, presumably because proprietary operative BMD systems could exceed their technical and financial resources and therefore degrade their larger military standing and sense of security in a post-MAD environment. Russian refusal to accept invitations to participate in NATO BMD may be indicative of the lack of an alternative to MAD in current Russian war-fighting strategy due to the dilapidation of conventional forces after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Proud Prophet

Proud Prophet was a series of war games played out by various American military officials. The simulation revealed MAD made the use of nuclear weapons virtually impossible without total nuclear annihilation, regardless of how nuclear weapons were implemented in war plans. These results essentially ruled out the possibility of a limited nuclear strike, as every time this was attempted, it resulted in a complete expenditure of nuclear weapons by both the United States and USSR. Proud Prophet marked a shift in American strategy; following Proud Prophet, American rhetoric of strategies that involved the use of nuclear weapons dissipated and American war plans were changed to emphasize the use of conventional forces.

TTAPS Study

In 1983, a group of researchers including Carl Sagan released the TTAPS study (named for the respective initials of the authors), which predicted that the large scale use of nuclear weapons would cause a “nuclear winter”. The study predicted that the debris burned in nuclear bombings would be lifted into the atmosphere and diminish sunlight worldwide, thus reducing world temperatures by “-15° to -25°C”. These findings led to theory that MAD would still occur with many less weapons than were possessed by either the United States or USSR at the height of the Cold War. As such, nuclear winter was used as an argument for significant reduction of nuclear weapons since MAD would occur anyway.

Post-Cold War

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation emerged as a sovereign entity encompassing most of the territory of the former USSR. Relations between the United States and Russia were, at least for a time, less tense than they had been with the Soviet Union.

While MAD has become less applicable for the US and Russia, it has been argued as a factor behind Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. Similarly, diplomats have warned that Japan may be pressured to nuclearize by the presence of North Korean nuclear weapons. The ability to launch a nuclear attack against an enemy city is a relevant deterrent strategy for these powers.

The administration of US President George W. Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in June 2002, claiming that the limited national missile defense system which they proposed to build was designed only to prevent nuclear blackmail by a state with limited nuclear capability and was not planned to alter the nuclear posture between Russia and the United States.

While relations have improved and an intentional nuclear exchange is more unlikely, the decay in Russian nuclear capability in the post-Cold War era may have had an effect on the continued viability of the MAD doctrine. A 2006 article by Keir Lieber and Daryl Press stated that the United States could carry out a nuclear first strike on Russia and would "have a good chance of destroying every Russian bomber base, submarine, and ICBM." This was attributed to reductions in Russian nuclear stockpiles and the increasing inefficiency and age of that which remains. Lieber and Press argued that the MAD era is coming to an end and that the United States is on the cusp of global nuclear primacy.

However, in a follow-up article in the same publication, others criticized the analysis, including Peter Flory, the US Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy, who began by writing "The essay by Keir Lieber and Daryl Press contains so many errors, on a topic of such gravity, that a Department of Defense response is required to correct the record." Regarding reductions in Russian stockpiles, another response stated that "a similarly one-sided examination of [reductions in] U.S. forces would have painted a similarly dire portrait".

A situation in which the United States might actually be expected to carry out a "successful" attack is perceived as a disadvantage for both countries. The strategic balance between the United States and Russia is becoming less stable, and the objective, the technical possibility of a first strike by the United States is increasing. At a time of crisis, this instability could lead to an accidental nuclear war. For example, if Russia feared a US nuclear attack, Moscow might make rash moves (such as putting its forces on alert) that would provoke a US preemptive strike.

An outline of current US nuclear strategy toward both Russia and other nations was published as the document "Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence" in 1995.

In November 2020, the US successfully destroyed a dummy ICBM outside the atmosphere with another missile. Bloomberg Opinion writes that this defense ability "ends the era of nuclear stability".

India and Pakistan

MAD does not entirely apply to all nuclear-armed rivals. India and Pakistan are an example of this; because of the abject superiority of conventional Indian armed forces to their Pakistani counterparts, Pakistan may be forced to use their nuclear weapons on invading Indian forces out of desperation regardless of an Indian retaliatory strike. As such, any large-scale attack on Pakistan by India could precipitate the use of nuclear weapons by Pakistan, thus rendering MAD inapplicable. However, MAD is applicable in that it may deter Pakistan from making a “suicidal” nuclear attack rather than a defensive nuclear strike.

North Korea

Since the emergence of North Korea as a nuclear state, military action has not been an option in handling the instability surrounding North Korea because of their option of nuclear retaliation in response to any conventional attack on them, thus rendering non-nuclear neighboring states such as South Korea and Japan incapable of resolving the destabilizing effect of North Korea via military force. MAD may not apply to the situation in North Korea because the theory relies on rational consideration of the use and consequences of nuclear weapons, which may not be the case for potential North Korean deployment.

Official policy

Whether MAD was the officially accepted doctrine of the United States military during the Cold War is largely a matter of interpretation. The United States Air Force, for example, has retrospectively contended that it never advocated MAD as a sole strategy, and that this form of deterrence was seen as one of numerous options in US nuclear policy. Former officers have emphasized that they never felt as limited by the logic of MAD (and were prepared to use nuclear weapons in smaller-scale situations than "assured destruction" allowed), and did not deliberately target civilian cities (though they acknowledge that the result of a "purely military" attack would certainly devastate the cities as well). However, according to a declassified 1959 Strategic Air Command study, US nuclear weapons plans specifically targeted the populations of Beijing, Moscow, Leningrad, East Berlin, and Warsaw for systematic destruction. MAD was implied in several US policies and used in the political rhetoric of leaders in both the United States and the USSR during many periods of the Cold War.

To continue to deter in an era of strategic nuclear equivalence, it is necessary to have nuclear (as well as conventional) forces such that in considering aggression against our interests any adversary would recognize that no plausible outcome would represent a victory or any plausible definition of victory. To this end and so as to preserve the possibility of bargaining effectively to terminate the war on acceptable terms that are as favorable as practical, if deterrence fails initially, we must be capable of fighting successfully so that the adversary would not achieve his war aims and would suffer costs that are unacceptable, or in any event greater than his gains, from having initiated an attack.

— President Jimmy Carter in 1980, Presidential Directive 59, Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy

The doctrine of MAD was officially at odds with that of the USSR, which had, contrary to MAD, insisted survival was possible. The Soviets believed they could win not only a strategic nuclear war, which they planned to absorb with their extensive civil defense planning, but also the conventional war that they predicted would follow after their strategic nuclear arsenal had been depleted. Official Soviet policy, though, may have had internal critics towards the end of the Cold War, including some in the USSR's own leadership.

Nuclear use would be catastrophic.

— 1981, the Soviet General Staff

Other evidence of this comes from the Soviet minister of defense, Dmitriy Ustinov, who wrote that "A clear appreciation by the Soviet leadership of what a war under contemporary conditions would mean for mankind determines the active position of the USSR." The Soviet doctrine, although being seen as primarily offensive by Western analysts, fully rejected the possibility of a "limited" nuclear war by 1975.

Criticism

Challengeable assumptions

- Second-strike capability

- A first strike must not be capable of preventing a retaliatory second strike or else mutual destruction is not assured. In this case, a state would have nothing to lose with a first strike, or might try to preempt the development of an opponent's second-strike capability with a first strike. To avoid this, countries may design their nuclear forces to make decapitation strike almost impossible, by dispersing launchers over wide areas and using a combination of sea-based, air-based, underground, and mobile land-based launchers.

- Another case of ensuring second strike capability is the Soviet (now Russian-operated) Dead Hand system, which is a semi-automatic “version of Dr. Strangelove’s Doomsday Machine”, which upon activation can launch a second strike without human intervention. The purpose of the Dead Hand system is to ensure a second strike even if Russia were to suffer a decapitation attack, thus maintaining MAD.

- Perfect detection

- No false positives (errors) in the equipment and/or procedures that must identify a launch by the other side. The implication of this is that an accident could lead to a full nuclear exchange. During the Cold War there were several instances of false positives, as in the case of Stanislav Petrov.

- Perfect attribution. If there is a launch from the Sino-Russian border, it could be difficult to distinguish which nation is responsible—both Russia and China have the capability—and, hence, against which nation retaliation should occur. A launch from a nuclear-armed submarine could also be difficult to attribute.

- Perfect rationality

- No rogue commanders will have the ability to corrupt the launch decision process. Such an incident very nearly occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis when an argument broke out aboard a nuclear-armed submarine cut off from radio communication. The second-in-command, Vasili Arkhipov, refused to launch despite an order from Captain Savitsky to do so.

- All leaders with launch capability care about the survival of their subjects (an extremist leader may welcome Armageddon and launch an unprovoked attack). Winston Churchill warned that any strategy will not "cover the case of lunatics or dictators in the mood of Hitler when he found himself in his final dugout."

- Inability to defend

- No fallout shelter networks of sufficient capacity to protect large segments of the population and/or industry.

- No development of anti-missile technology or deployment of remedial protective gear.

Terrorism

- The threat of foreign and domestic nuclear terrorist threats has been a criticism of MAD as a defensive strategy. Deterrent strategies are ineffective against those who attack without regard for their life. Furthermore, the doctrine of MAD has been critiqued in regard to terrorism and asymmetrical warfare. Critics contend that a retaliatory strike would not be possible in this case because of the decentralization of terrorist organizations, which may be operating in several countries and dispersed among civilian populations. A misguided retaliatory strike made by the targeted nation could even advance terrorist goals in that a contentious retaliatory strike could drive support for the terrorist cause that instigated the nuclear exchange.

Space Weapons

- Strategic analysts have criticized the doctrine of MAD for its inability to respond to the proliferation of space weaponry. First, military space systems have unequal dependence across countries. This means that less-dependent countries may find it beneficial to attack a more-dependent country’s space weapons, which complicates deterrence. This is especially true for countries like North Korea which have extensive ballistic missiles that could strike space-based systems. Even across countries with similar dependence, anti-satellite weapons (ASATs) have the ability to remove the command and control of nuclear weapons. This encourages crisis-instability and pre-emptive nuclear-disabling strikes. Third, there is a risk of asymmetrical challengers. Countries that fall behind in space weapon advancement may turn to using chemical or biological weapons. This may heighten the risk of escalation, bypassing any deterrent effects of nuclear weapons.

Entanglements

- Cold-war bipolarity no longer is applicable to the global power balance. The complex modern alliance system makes allies and enemies tied to one another. Thus, action by one country to deter another could threaten the safety of a third country. “Security trilemmas” could increase tension during mundane acts of cooperation, complicating MAD.

Emerging Hypersonic Weapons

- Hypersonic ballistic or cruise missiles threaten the retaliatory backbone of mutually assured destruction. The high precision and speed of these weapons may allow for the development of “decapitory” strikes that remove the ability of another nation to have a nuclear response. In addition, the secretive nature of these weapon’s development can make deterrence more asymmetrical.

Failure to Retaliate

- If it was known that a country’s leader would not resort to nuclear retaliation, adversaries may be emboldened. Edward Teller, a member of the Manhattan Project, echoed these concerns as early as 1985 when he said that “The MAD policy as a deterrent is totally ineffective if it becomes known that in case of attack, we would not retaliate against the aggressor.”