In the ego psychology model of the psyche, the id is the set of uncoordinated instinctual desires; the superego plays the critical and moralizing role; and the ego is the organized, realistic agent that mediates between the instinctual desires of the id and the critical superego; Freud compared the ego (in its relation to the id) to a man on horseback: the rider must harness and direct the superior energy of his mount, and at times allow for a practicable satisfaction of its urges. The ego is thus "in the habit of transforming the id's will into action, as if it were its own."

Freud introduced the structural model (id, ego, superego) in the essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) in response to the unstructured ambiguity and conflicting uses of the term "the unconscious mind". He elaborated, refined, and formalized that model in the essay The Ego and the Id (1923).

Translation of the terms

The terms "id", "ego", and "superego" are not Freud's own; they are Latinizations by his translator James Strachey. Freud himself wrote of "das Es", "das Ich", and "das Über-Ich"—respectively, "the It", "the I", and "the Over-I". Thus, to the German reader, Freud's original terms are to some degree self-explanatory. The term "das Es" was originally used by Georg Groddeck, a physician whose unconventional ideas were of interest to Freud (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It"). The word ego is taken directly from Latin, where it is the nominative of the first person singular personal pronoun and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. Figures like Bruno Bettelheim have criticized the way "the English translations impeded students' efforts to gain a true understanding of Freud" by substituting the formalised language of the elaborated code for the quotidian immediacy of Freud's own language.

Psychic apparatus

Id

Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of bodily needs and wants, emotional impulses and desires, especially aggression and the sexual drive. The id acts according to the pleasure principle—the psychic force oriented to immediate gratification of impulse and desire.

Freud described the id as "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". Understanding of the id is limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and it can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: it is concerned only with satisfaction of drives in accordance with the pleasure principle. It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time." The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."

Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle. The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the principle of reality into account.

Freud describes the id as "the great reservoir of libido", the energy of desire, usually conceived as sexual in nature, the life instincts that are constantly seeking a renewal of life. He later also postulated a death drive, which seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state." For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms" through aggression. Since the id includes all instinctual impulses, the destructive instinct, as well as eros or the life instincts, is considered to be part of the id.

Ego

The ego acts according to the reality principle. Since the id's drives are frequently incompatible with social reality, the ego attempts to direct its energy and satisfy its demands in accordance with the imperatives of that reality. According to Freud the ego, in its role as mediator between the id and reality, is often "obliged to cloak the (unconscious) commands of the id with its own preconscious rationalizations, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."

Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean the sense of self, but later expanded it to include psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego is the organizing principle upon which thoughts and interpretations of the world are based.

According to Freud, "the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions... it is like a tug of war... with the difference that in the tug of war the teams fight against one another in equality, while the ego is against the much stronger 'id'." In fact, the ego is required to serve "three severe masters...the external world, the superego and the id." It seeks to find a balance between the primitive drives of the id, the limitations imposed by reality, and the strictures of the superego. It is concerned with self-preservation: it strives to keep the id's desires within limits, adapted to reality and submissive to the superego.

Thus "driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality" the ego struggles to bring about harmony among the competing forces. Consequently, it can easily be subject to "realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the superego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id." The ego may wish to serve the id, trying to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts, while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the superego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority.

To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms reduce the tension and anxiety by disguising or transforming the impulses that are perceived as threatening. Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. His daughter Anna Freud identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatization, splitting, and substitution.

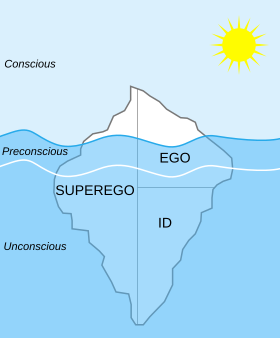

In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted as being half in the conscious, a quarter in the preconscious, and the other quarter in the unconscious.

Superego

The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly as absorbed from parents, but also other authority figures, and the general cultural ethos. Freud developed his concept of the superego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the "special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our 'conscience'." For him the superego can be described as "a successful instance of identification with the parental agency", and as development proceeds it also absorbs the influence of those who have "stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models".

Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.

The superego aims for perfection. It is the part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency, commonly called "conscience", that criticizes and prohibits the expression of drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. Thus the superego works in contradiction to the id. It is an internalized mechanism that operates to confine the ego to socially acceptable behaviour, whereas the id merely seeks instant self-gratification.

The superego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex. In the case of the little boy, it forms during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex, through a process of identification with the father figure, following the failure to retain possession of the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration. Freud described the superego and its relationship to the father figure and Oedipus complex thus:

The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.

In The Ego and the Id, Freud presents "the general character of harshness and cruelty exhibited by the [ego] ideal — its dictatorial Thou shalt". The earlier in the child's development, the greater the estimate of parental power.

. . . nor must it be forgotten that a child has a different estimate of his parents at different periods of his life. At the time at which the Oedipus complex gives place to the super-ego they are something quite magnificent; but later, they lose much of this. Identifications then come about with these later parents as well, and indeed they regularly make important contributions to the formation of character; but in that case they only affect the ego, they no longer influence the super-ego, which has been determined by the earliest parental images.

— New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 64.

Thus when the child is in rivalry with the parental imago it feels the dictatorial Thou shalt—the manifest power that the imago represents—on four levels: (i) the auto-erotic, (ii) the narcissistic, (iii) the anal, and (iv) the phallic. Those different levels of mental development, and their relations to parental imagos, correspond to specific id forms of aggression and affection.

The concept of superego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore, for Freud, "their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men...they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility." However, Freud went on to modify his position to the effect "that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their human identity, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics, otherwise known as human characteristics."

Advantages of the structural model

In his earlier "topographic model", Freud divided the psyche into three "regions" or "systems": "the Conscious", that which is present to awareness at the surface level of the psyche in any given moment, including information and stimuli from both internal and external sources; "the Preconscious", consisting of material that is merely latent, not present to consciousness but capable of becoming so; and "the Unconscious", consisting of ideas and impulses that are made completely inaccessible to consciousness by the act of repression. By introducing the structural model, Freud was seeking to reduce his reliance on the term "unconscious" in its systematic and topographic sense—as the mental region that is foreign to the ego—by replacing it with the concept of the 'id'." The partition of the psyche outlined in the structural model is thus one that cuts across the topographical model's partition of "conscious vs. unconscious".

Freud favoured the structural model because of the increased degree of precision and diversification that it allowed. Although the id is unconscious by definition, the ego and the superego are both partly conscious and partly unconscious. With the new model, Freud felt he had achieved a more effective classification system for mental disorders than had been available previously:

Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to one between the ego and the external world.

The three newly presented entities, however, remained closely connected to their previous conceptions, including those that went under different names – the systematic unconscious for the id, and the conscience/ego ideal for the superego. Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, though he noted that "the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples...we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement."

The iceberg metaphor is a commonly used visual metaphor depicting the relationship between the ego, id and superego agencies (structural model) and the conscious and unconscious psychic systems (topographic model). In the iceberg metaphor the entire id and part of both the superego and the ego are submerged in the underwater portion representing the unconscious region of the psyche. The remaining portions of the ego and superego are displayed above water in the conscious region.