Ernst Haeckel | |

|---|---|

| |

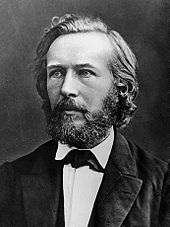

| Born | Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel 16 February 1834 |

| Died | 9 August 1919 (aged 85) Jena, Germany |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Recapitulation theory |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Sethe, Agnes Huschke |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | University of Jena |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Haeckel |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Haeckel |

| Signature | |

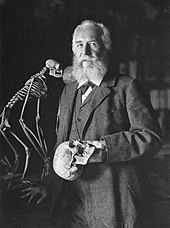

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (German: [ɛʁnst ˈhɛkl̩]; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms and coined many terms in biology, including ecology, phylum, phylogeny, and Protista. Haeckel promoted and popularised Charles Darwin's work in Germany and developed the influential but no longer widely held recapitulation theory ("ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny") claiming that an individual organism's biological development, or ontogeny, parallels and summarises its species' evolutionary development, or phylogeny.

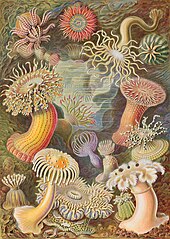

The published artwork of Haeckel includes over 100 detailed, multi-colour illustrations of animals and sea creatures, collected in his Kunstformen der Natur ("Art Forms of Nature"), a book which would go on to influence the Art Nouveau artistic movement. As a philosopher, Ernst Haeckel wrote Die Welträthsel (1895–1899; in English: The Riddle of the Universe, 1901), the genesis for the term "world riddle" (Welträtsel); and Freedom in Science and Teaching to support teaching evolution.

Haeckel was also a promoter of scientific racism and embraced the idea of Social Darwinism. He was the first person to characterize the Great War the "first" World War, which he did as early as 1914.

Life

Ernst Haeckel was born on 16 February 1834, in Potsdam (then part of the Kingdom of Prussia). In 1852 Haeckel completed studies at the Domgymnasium, the cathedral high-school of Merseburg. He then studied medicine in Berlin and Würzburg, particularly with Albert von Kölliker, Franz Leydig, Rudolf Virchow (with whom he later worked briefly as assistant), and with the anatomist-physiologist Johannes Peter Müller (1801–1858). Together with Hermann Steudner he attended botany lectures in Würzburg. In 1857 Haeckel attained a doctorate in medicine, and afterwards he received the license to practice medicine. The occupation of physician appeared less worthwhile to Haeckel after contact with suffering patients.

He studied under Carl Gegenbaur at the University of Jena for three years, earning a habilitation in comparative anatomy in 1861, before becoming a professor of zoology at the University at Jena, where he remained for 47 years, from 1862 to 1909. Between 1859 and 1866 Haeckel worked on many phyla, such as radiolarians, poriferans (sponges) and annelids (segmented worms). During a trip to the Mediterranean, Haeckel named nearly 150 new species of radiolarians.

In 1864, his first wife, Anna Sethe, died. Haeckel dedicated some species of jellyfish that he found beautiful (such as Desmonema annasethe) to her.

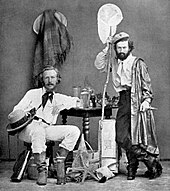

From 1866 to 1867 Haeckel made an extended journey to the Canary Islands with Hermann Fol. On 17 October 1866 he arrived in London. Over the next few days he met Charles Lyell, and visited Thomas Huxley and family at their home. On 21 October he visited Charles Darwin at Down House in Kent. In 1867 he married Agnes Huschke. Their son Walter was born in 1868, their daughters Elizabeth in 1871 and Emma in 1873. In 1869 he traveled as a researcher to Norway, in 1871 to Croatia (where he lived on the island of Hvar in a monastery), and in 1873 to Egypt, Turkey, and Greece. In 1907 he had a museum built in Jena to teach the public about evolution. Haeckel retired from teaching in 1909, and in 1910 he withdrew from the Evangelical Church of Prussia.

On the occasion of his 80th birthday celebration he was presented with a two-volume work entitled Was wir Ernst Haeckel verdanken (What We Owe to Ernst Haeckel), edited at the request of the German Monistenbund by Heinrich Schmidt of Jena.

Haeckel's wife, Agnes, died in 1915, and he became substantially frailer, breaking his leg and arm. He sold his "Villa Medusa" in Jena in 1918 to the Carl Zeiss foundation, which preserved his library. Haeckel died on 9 August 1919.

Haeckel became the most famous proponent of Monism in Germany.

Politics

Haeckel's affinity for the German Romantic movement, coupled with his acceptance of a form of Lamarckism, influenced his political beliefs. Rather than being a strict Darwinian, Haeckel believed that the characteristics of an organism were acquired through interactions with the environment and that ontogeny reflected phylogeny. He saw the social sciences as instances of "applied biology", and that phrase was picked up and used for Nazi propaganda.

In 1906 Haeckel belonged to the founders of the Monist League (Deutscher Monistenbund), which took a stance against philosophical materialism and promote a "natural Weltanschauung". This organization lasted until 1933 and included such notable members as Wilhelm Ostwald, Georg von Arco (1869–1940), Helene Stöcker and Walter Arthur Berendsohn. He was the first person to use the term "first world war" about World War I.

However, Haeckel's books were banned by the Nazi Party, which refused Monism and Haeckel's freedom of thought. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that Haeckel had often overtly recognized the great contribution of educated Jews to the German culture.

Research

Haeckel was a zoologist, an accomplished artist and illustrator, and later a professor of comparative anatomy. Although Haeckel's ideas are important to the history of evolutionary theory, and although he was a competent invertebrate anatomist most famous for his work on radiolaria, many speculative concepts that he championed are now considered incorrect. For example, Haeckel described and named hypothetical ancestral microorganisms that have never been found.

He was one of the first to consider psychology as a branch of physiology. He also proposed the kingdom Protista in 1866. His chief interests lay in evolution and life development processes in general, including development of nonrandom form, which culminated in the beautifully illustrated Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms of nature). Haeckel did not support natural selection, rather believing in Lamarckism.

Haeckel advanced a version of the earlier recapitulation theory previously set out by Étienne Serres in the 1820s and supported by followers of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire including Robert Edmond Grant. It proposed a link between ontogeny (development of form) and phylogeny (evolutionary descent), summed up by Haeckel in the phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". His concept of recapitulation has been refuted in the form he gave it (now called "strong recapitulation"), in favour of the ideas first advanced by Karl Ernst von Baer. The strong recapitulation hypothesis views ontogeny as repeating forms of adult ancestors, while weak recapitulation means that what is repeated (and built upon) is the ancestral embryonic development process. Haeckel supported the theory with embryo drawings that have since been shown to be oversimplified and in part inaccurate, and the theory is now considered an oversimplification of quite complicated relationships, however comparison of embryos remains a powerful way to demonstrate that all animals are related. Haeckel introduced the concept of heterochrony, the change in timing of embryonic development over the course of evolution.

Haeckel was a flamboyant figure, who sometimes took great, non-scientific leaps from available evidence. For example, at the time when Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), Haeckel postulated that evidence of human evolution would be found in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). At that time, no remains of human ancestors had yet been identified. He described these theoretical remains in great detail and even named the as-yet unfound species, Pithecanthropus alalus, and instructed his students such as Richard and Oskar Hertwig to go and find it.

One student did find some remains: a Dutchman named Eugène Dubois searched the East Indies from 1887 to 1895, discovering the remains of Java Man in 1891, consisting of a skullcap, thighbone, and a few teeth. These remains are among the oldest hominid remains ever found. Dubois classified Java Man with Haeckel's Pithecanthropus label, though they were later reclassified as Homo erectus. Some scientists of the day suggested Dubois' Java Man as a potential intermediate form between modern humans and the common ancestor we share with the other great apes. The current consensus of anthropologists is that the direct ancestors of modern humans were African populations of Homo erectus (possibly Homo ergaster), rather than the Asian populations exemplified by Java Man and Peking Man. (Ironically, a new human species, Homo floresiensis, a dwarf human type, has recently been discovered in the island of Flores).

Polygenism and racial theory

The creationist polygenism of Samuel George Morton and Louis Agassiz, which presented human races as separately created species, was rejected by Charles Darwin, who argued for the monogenesis of the human species and the African origin of modern humans. In contrast to most of Darwin's supporters, Haeckel put forward a doctrine of evolutionary polygenism based on the ideas of the linguist August Schleicher, in which several different language groups had arisen separately from speechless prehuman Urmenschen (German: proto-humans), which themselves had evolved from simian ancestors. These separate languages had completed the transition from animals to man, and under the influence of each main branch of languages, humans had evolved – in a kind of Lamarckian use-inheritance – as separate species, which could be subdivided into races. From this, Haeckel drew the implication that languages with the most potential yield the human races with the most potential, led by the Semitic and Indo-Germanic groups, with Berber, Jewish, Greco-Roman and Germanic varieties to the fore. As Haeckel stated:

We must mention here one of the most important results of the comparative study of languages, which for the Stammbaum of the species of men is of the highest significance, namely that human languages probably had a multiple or polyphyletic origin. Human language as such probably developed only after the species of speechless Urmenschen or Affenmenschen (German: ape-men) had split into several species or kinds. With each of these human species, language developed on its own and independently of the others. At least this is the view of Schleicher, one of the foremost authorities on this subject. ... If one views the origin of the branches of language as the special and principal act of becoming human, and the species of humankind as distinguished according to their language stem, then one can say that the different species of men arose independently of one another.

Haeckel's view can be seen as a forerunner of the views of Carleton Coon, who also believed that human races evolved independently and in parallel with each other. These ideas eventually fell from favour.

Haeckel also applied the hypothesis of polygenism to the modern diversity of human groups. He became a key figure in social darwinism and leading proponent of scientific racism, stating for instance:

The Caucasian, or Mediterranean man (Homo Mediterraneus), has from time immemorial been placed at the head of all the races of men, as the most highly developed and perfect. It is generally called the Caucasian race, but as, among all the varieties of the species, the Caucasian branch is the least important, we prefer the much more suitable appellation proposed by Friedrich Müller, namely, that of Mediterranese. For the most important varieties of this species, which are moreover the most eminent actors in what is called "Universal History", first rose to a flourishing condition on the shores of the Mediterranean. ... This species alone (with the exception of the Mongolian) has had an actual history; it alone has attained to that degree of civilisation which seems to raise men above the rest of nature.

Haeckel divided human beings into ten races, of which the Caucasian was the highest and the primitives were doomed to extinction. In his view, 'Negroes' were savages and Whites were the most civilised: for instance, he claimed that '[t]he Negro' had stronger and more freely movable toes than any other race, which, he argued, was evidence of their being less evolved, and which led him to compare them to '"four-handed" Apes'.

In his Ontogeny and Phylogeny Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote: "[Haeckel's] evolutionary racism; his call to the German people for racial purity and unflinching devotion to a 'just' state; his belief that harsh, inexorable laws of evolution ruled human civilization and nature alike, conferring upon favored races the right to dominate others ... all contributed to the rise of Nazism."

In his introduction to the Nazi party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg's 1930 book, [The Myth of the Twentieth Century], Peter Peel affirms that Rosenberg had indeed read Haeckel.

In the same line of thought, historian Daniel Gasman states that Haeckel's ideology stimulated the birth of Fascist ideology in Italy and France.

However, Robert J. Richards notes: "Haeckel, on his travels to Ceylon and Indonesia, often formed closer and more intimate relations with natives, even members of the untouchable classes, than with the European colonials." and says the Nazis rejected Haeckel, since he opposed antisemitism, while supporting ideas they disliked (for instance atheism, feminism, internationalism, pacifism etc.).

The Jena Declaration, published by the German Zoological Society, rejects the idea of human "races" and distances itself from the racial theories of Ernst Haeckel and other 20th century scientists. It claims that genetic variation between human populations is smaller than within them, demonstrating that the biological concept of "races" is invalid. The statement highlights that there are no specific genes or genetic markers that match with conventional racial categorizations. It also indicates that the idea of "races" is based on racism rather than any scientific factuality.

Asia hypothesis

Haeckel claimed the origin of humanity was to be found in Asia: he believed that Hindustan (Indian subcontinent) was the actual location where the first humans had evolved. Haeckel argued that humans were closely related to the primates of Southeast Asia and rejected Darwin's hypothesis of Africa.

Haeckel later claimed that the missing link was to be found on the lost continent of Lemuria located in the Indian Ocean. He believed that Lemuria was the home of the first humans and that Asia was the home of many of the earliest primates; he thus supported that Asia was the cradle of hominid evolution. Haeckel also claimed that Lemuria connected Asia and Africa, which allowed the migration of humans to the rest of the world.

In Haeckel's book The History of Creation (1884) he included migration routes which he thought the first humans had used outside of Lemuria.

Religious views

In Monism as Connecting Religion and Science (1892), he argued in favor of monism as the view most compatible with the current scientific understanding of the natural world. His perspective of monism was pantheistic and impersonal.

The monistic idea of God, which alone is compatible with our present knowledge of nature, recognizes the divine spirit in all things. It can never recognise in God a "personal being," or, in other words, an individual of limited extension in space, or even of human form. God is everywhere.

Embryology and recapitulation theory

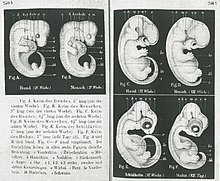

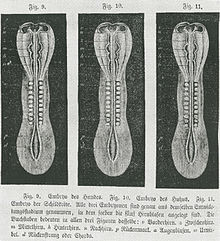

When Haeckel was a student in the 1850s he showed great interest in embryology, attending the rather unpopular lectures twice and in his notes sketched the visual aids: textbooks had few illustrations, and large format plates were used to show students how to see the tiny forms under a reflecting microscope, with the translucent tissues seen against a black background. Developmental series were used to show stages within a species, but inconsistent views and stages made it even more difficult to compare different species. It was agreed by all European evolutionists that all vertebrates looked very similar at an early stage, in what was thought of as a common ideal type, but there was a continuing debate from the 1820s between the Romantic recapitulation theory that human embryos developed through stages of the forms of all the major groups of adult animals, literally manifesting a sequence of organisms on a linear chain of being, and Karl Ernst von Baer's opposing view, stated in von Baer's laws of embryology, that the early general forms diverged into four major groups of specialised forms without ever resembling the adult of another species, showing affinity to an archetype but no relation to other types or any transmutation of species. By the time Haeckel was teaching he was able to use a textbook with woodcut illustrations written by his own teacher Albert von Kölliker, which purported to explain human development while also using other mammalian embryos to claim a coherent sequence. Despite the significance to ideas of transformism, this was not really polite enough for the new popular science writing, and was a matter for medical institutions and for experts who could make their own comparisons.

Darwin, Naturphilosophie and Lamarck

Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which made a powerful impression on Haeckel when he read it in 1864, was very cautious about the possibility of ever reconstructing the history of life, but did include a section reinterpreting von Baer's embryology and revolutionising the field of study, concluding that "Embryology rises greatly in interest, when we thus look at the embryo as a picture, more or less obscured, of the common parent-form of each great class of animals." It mentioned von Baer's 1828 anecdote (misattributing it to Louis Agassiz) that at an early stage embryos were so similar that it could be impossible to tell whether an unlabelled specimen was of a mammal, a bird, or of a reptile, and Darwin's own research using embryonic stages of barnacles to show that they are crustaceans, while cautioning against the idea that one organism or embryonic stage is "higher" or "lower", or more or less evolved. Haeckel disregarded such caution, and in a year wrote his massive and ambitious Generelle Morphologie, published in 1866, presenting a revolutionary new synthesis of Darwin's ideas with the German tradition of Naturphilosophie going back to Goethe and with the progressive evolutionism of Lamarck in what he called Darwinismus. He used morphology to reconstruct the evolutionary history of life, in the absence of fossil evidence using embryology as evidence of ancestral relationships. He invented new terms, including ontogeny and phylogeny, to present his evolutionised recapitulation theory that "ontogeny recapitulated phylogeny". The two massive volumes sold poorly, and were heavy going: with his limited understanding of German, Darwin found them impossible to read. Haeckel's publisher turned down a proposal for a "strictly scholarly and objective" second edition.

Embryological drawings

Haeckel's aim was a reformed morphology with evolution as the organising principle of a cosmic synthesis unifying science, religion, and art. He was giving successful "popular lectures" on his ideas to students and townspeople in Jena, in an approach pioneered by his teacher Rudolf Virchow. To meet his publisher's need for a popular work he used a student's transcript of his lectures as the basis of his Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte of 1868, presenting a comprehensive presentation of evolution. In the Spring of that year he drew figures for the book, synthesising his views of specimens in Jena and published pictures to represent types. After publication he told a colleague that the images "are completely exact, partly copied from nature, partly assembled from all illustrations of these early stages that have hitherto become known". There were various styles of embryological drawings at that time, ranging from more schematic representations to "naturalistic" illustrations of specific specimens. Haeckel believed privately that his figures were both exact and synthetic, and in public asserted that they were schematic like most figures used in teaching. The images were reworked to match in size and orientation, and though displaying Haeckel's own views of essential features, they support von Baer's concept that vertebrate embryos begin similarly and then diverge. Relating different images on a grid conveyed a powerful evolutionary message. As a book for the general public, it followed the common practice of not citing sources.

The book sold very well, and while some anatomical experts hostile to Haeckel's evolutionary views expressed some private concerns that certain figures had been drawn rather freely, the figures showed what they already knew about similarities in embryos. The first published concerns came from Ludwig Rütimeyer, a professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Basel who had placed fossil mammals in an evolutionary lineage early in the 1860s and had been sent a complimentary copy. At the end of 1868 his review in the Archiv für Anthropologie wondered about the claim that the work was "popular and scholarly", doubting whether the second was true, and expressed horror about such public discussion of man's place in nature with illustrations such as the evolutionary trees being shown to non-experts. Though he made no suggestion that embryo illustrations should be directly based on specimens, to him the subject demanded the utmost "scrupulosity and conscientiousness" and an artist must "not arbitrarily model or generalise his originals for speculative purposes" which he considered proved by comparison with works by other authors. In particular, "one and the same, moreover incorrectly interpreted woodcut, is presented to the reader three times in a row and with three different captions as [the] embryo of the dog, the chick, [and] the turtle". He accused Haeckel of "playing fast and loose with the public and with science", and failing to live up to the obligation to the truth of every serious researcher. Haeckel responded with angry accusations of bowing to religious prejudice, but in the second (1870) edition changed the duplicated embryo images to a single image captioned "embryo of a mammal or bird". Duplication using galvanoplastic stereotypes (clichés) was a common technique in textbooks, but not on the same page to represent different eggs or embryos. In 1891 Haeckel made the excuse that this "extremely rash foolishness" had occurred in undue haste but was "bona fide", and since repetition of incidental details was obvious on close inspection, it is unlikely to have been intentional deception.

The revised 1870 second edition of 1,500 copies attracted more attention, being quickly followed by further revised editions with larger print runs as the book became a prominent part of the optimistic, nationalist, anticlerical "culture of progress" in Otto von Bismarck's new German Empire. The similarity of early vertebrate embryos became common knowledge, and the illustrations were praised by experts such as Michael Foster of the University of Cambridge. In the introduction to his 1871 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin gave particular praise to Haeckel, writing that if Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte "had appeared before my essay had been written, I should probably never have completed it". The first chapter included an illustration: "As some of my readers may never have seen a drawing of an embryo, I have given one of man and another of a dog, at about the same early stage of development, carefully copied from two works of undoubted accuracy" with a footnote citing the sources and noting that "Häckel has also given analogous drawings in his Schöpfungsgeschichte." The fifth edition of Haeckel's book appeared in 1874, with its frontispiece a heroic portrait of Haeckel himself, replacing the previous controversial image of the heads of apes and humans.

Controversy

Later in 1874, Haeckel's simplified embryology textbook Anthropogenie made the subject into a battleground over Darwinism aligned with Bismarck's Kulturkampf ("culture struggle") against the Catholic Church. Haeckel took particular care over the illustrations, changing to the leading zoological publisher Wilhelm Engelmann of Leipzig and obtaining from them use of illustrations from their other textbooks as well as preparing his own drawings including a dramatic double page illustration showing "early", "somewhat later" and "still later" stages of 8 different vertebrates. Though Haeckel's views had attracted continuing controversy, there had been little dispute about the embryos and he had many expert supporters, but Wilhelm His revived the earlier criticisms and introduced new attacks on the 1874 illustrations. Others joined in: both expert anatomists and Catholic priests and supporters were politically opposed to Haeckel's views.

While it has been widely claimed that Haeckel was charged with fraud by five professors and convicted by a university court at Jena, there does not appear to be an independently verifiable source for this claim. Recent analyses (Richardson 1998, Richardson and Keuck 2002) have found that some of the criticisms of Haeckel's embryo drawings were legitimate, but others were unfounded. There were multiple versions of the embryo drawings, and Haeckel rejected the claims of fraud. It was later said that "there is evidence of sleight of hand" on both sides of the feud between Haeckel and Wilhelm His. Robert J. Richards, in a paper published in 2008, defends the case for Haeckel, shedding doubt against the fraud accusations based on the material used for comparison with what Haeckel could access at the time.

Awards and honors

Haeckel was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1885. He was awarded the title of Excellency by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1907 and the Linnean Society of London's prestigious Darwin-Wallace Medal in 1908. In the United States, Mount Haeckel, a 13,418 ft (4,090 m) summit in the Eastern Sierra Nevada, overlooking the Evolution Basin, is named in his honour, as is another Mount Haeckel, a 2,941 m (9,649 ft) summit in New Zealand; and the asteroid 12323 Haeckel.

In Jena he is remembered with a monument at Herrenberg (erected in 1969), an exhibition at Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, and at the Jena Phyletic Museum, which continues to teach about evolution and share his work to this day.

The ratfish, Harriotta haeckeli is named in his honor.

The research vessel Ernst Haeckel is named in his honor.

In 1981, a botanical journal called Ernstia was started being published in the city of Maracay, Venezuela.

In 2013, Ernstia, a genus of calcareous sponges in the family Clathrinidae. The genus was erected to contain five species previously assigned to Clathrina. The genus name honors Ernst Haeckel for his contributions towards sponge taxonomy and phylogeny.

Publications

Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species had immense popular influence, but although its sales exceeded its publisher's hopes it was a technical book rather than a work of popular science: long, difficult and with few illustrations. One of Haeckel's books did a great deal to explain his version of "Darwinism" to the world. It was a bestselling, provocatively illustrated book in German, titled Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, published in Berlin in 1868, and translated into English as The History of Creation in 1876. Until 1909, eleven editions had appeared, as well as 25 translations into other languages. The Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte cemented Haeckel's reputation as one of Germany's most forceful popularizers of science. His Welträthsel were reprinted ten times after the book's first publication in 1899; ultimately, over 400,000 copies were sold.

Haeckel argued that human evolution consisted of precisely 22 phases, the 21st – the "missing link" – being a halfway step between apes and humans. He even formally named this missing link Pithecanthropus alalus, translated as "ape man without speech".

Haeckel's literary output was extensive, including many books, scientific papers, and illustrations.

Monographs

- Radiolaria (1862)

- Siphonophora (1869)

- Monera (1870)

- Calcareous Sponges (1872)

Challenger reports

- Deep-Sea Medusae (1881)

- Siphonophora (1888)

- Deep-Sea Keratosa (1889)

- Radiolaria (1887)

Books on biology and its philosophy

- Generelle Morphologie der Organismen: allgemeine Grundzüge der organischen Formen-Wissenschaft, mechanisch begründet durch die von Charles Darwin reformirte Descendenz-Theorie. (1866) Berlin (General morphology of organisms: general foundations of form-science, mechanically grounded by the descendance theory reformed by Charles Darwin)

- Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (1868); in English The History of Creation (1876; 6th ed.: New York, D. Appleton and Co., 1914, 2 volumes)

- Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre (1877), in English, Free Science and Free Teaching

- Die systematische Phylogenie (1894) – Systematic Phylogeny

- Anthropogenie, oder, Entwickelungsgeschichte des Menschen (in Italian). Torino: UTET. 1895.

- Die Welträthsel (1895–1899), also spelled Die Welträtsel – in English The Riddle of the Universe: At the Close of the Nineteenth Century, Translated by Joseph McCabe, New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1900.

- Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen (1898) (On our current understanding of the origin of man) – in English The Last Link, 1898

- Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken (1905) (The struggle over thought on evolution) – in English Last Words on Evolution: A Popular Retrospect and Summary, Translated from the Second Edition by Joseph McCabe, New York: Peter Eckler, Publisher; London: A. Owen & Co., 1906.

- Die Lebenswunder (1904) – in English The Wonders of Life

- Kristallseelen : Studien über das anorganische Leben (1917) (Crystal souls: studies on inorganic life)

Travel books

- Indische Reisebriefe (1882) – Travel notes of India

- Aus Insulinde: Malayische Reisebriefe (1901) – Travel notes of Malaysia

- Kunstformen der Natur (1904) – Art forms of Nature, Digital Edition (1924)

- Wanderbilder (1905) – "Travel Images"

- A visit to Ceylon

For a fuller list of works of and about Haeckel, see his entry in the German Wikisource.

Assessments of potential influence on Nazism

Some historians have seen Haeckel's social Darwinism as a forerunner to Nazi ideology. Others have denied the relationship altogether.

The evidence is in some respects ambiguous. On one hand, Haeckel was an advocate of scientific racism. He held that evolutionary biology had definitively proven that races were unequal in intelligence and ability, and that their lives were also of unequal value, e.g., "These lower races (such as the Veddahs or Australian negroes) are psychologically nearer to the mammals (apes or dogs) than to civilised Europeans; we must therefore, assign a totally different value to their lives." As a result of the "struggle for existence", it followed that the "lower" races would eventually be exterminated. He was also a social Darwinist who believed that "survival of the fittest" was a natural law, and that struggle led to improvement of the race. As an advocate of eugenics, he also believed that about 200,000 mentally and congenitally ill should be killed by a medical control board. This idea was later put into practice by Nazi Germany, as part of the Aktion T4 program. Alfred Ploetz, founder of the German Society for Racial Hygiene, praised Haeckel repeatedly, and invited him to become an honorary member. Haeckel accepted the invitation. Haeckel also believed that Germany should be governed by an authoritarian political system, and that inequalities both within and between societies were an inevitable product of evolutionary law. Haeckel was also an extreme German nationalist who believed strongly in the superiority of German culture.

On the other hand, Haeckel was not an anti-Semite. In the racial hierarchies he constructed Jews tended to appear closer to the top, rather than closer to the bottom as in Nazi racial thought. He was also a pacifist until the First World War, when he wrote propaganda in favor of the war. The principal arguments of historians who deny a meaningful connection between Haeckel and Nazism are that Haeckel's ideas were very common at the time, that Nazis were much more strongly influenced by other thinkers, and that Haeckel is properly classified as a 19th-century German liberal, rather than a forerunner to Nazism. They also point to incompatibilities between evolutionary biology and Nazi ideology.

Nazis themselves divided on the question of whether Haeckel should be counted as a pioneer of their ideology. SS captain and biologist Heinz Brücher wrote a biography of Haeckel in 1936, in which he praised Haeckel as a "pioneer in biological state thinking". This opinion was also shared by the scholarly journal, Der Biologe, which celebrated Haeckel's 100th birthday, in 1934, with several essays acclaiming him as a pioneering thinker of Nazism. Other Nazis kept their distance from Haeckel. Nazi propaganda guidelines issued in 1935 listed books which popularized Darwin and evolution on an "expunged list". Haeckel was included by name as a forbidden author. Gunther Hecht, a member of the Nazi Department of Race Politics, also issued a memorandum rejecting Haeckel as a forerunner of Nazism. Kurt Hildebrandt, a Nazi political philosopher, also rejected Haeckel. Eventually Haeckel was rejected by Nazi bureaucrats.