Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics is the management of the flow of things between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of customers or corporations. The resources managed in logistics may include tangible goods such as materials, equipment, and supplies, as well as food and other consumable items.

In military science, logistics is concerned with maintaining army supply lines while disrupting those of the enemy, since an armed force without resources and transportation is defenseless. Military logistics was already practiced in the ancient world and as the modern military has a significant need for logistics solutions, advanced implementations have been developed. In military logistics, logistics officers manage how and when to move resources to the places they are needed.

Logistics management is the part of supply chain management and supply chain engineering that plans, implements, and controls the efficient, effective forward, and reverse flow and storage of goods, services, and related information between the point of origin and point of consumption to meet customers' requirements. The complexity of logistics can be modeled, analyzed, visualized, and optimized by dedicated simulation software. The minimization of the use of resources is a common motivation in all logistics fields. A professional working in the field of logistics management is called a logistician.

Nomenclature

The term logistics is attested in English from 1846, and is from French: logistique, where it was either coined or popularized by military officer and writer Antoine-Henri Jomini, who defined it in his Summary of the Art of War (Précis de l'Art de la Guerre). The term appears in the 1830 edition, then titled Analytic Table (Tableau Analytique), and Jomini explains that it is derived from French: logis, lit. 'lodgings' (cognate to English lodge), in the terms French: maréchal des logis, lit. 'marshall of lodgings' and French: major-général des logis, lit. 'major-general of lodging':

Autrefois les officiers de l’état-major se nommaient: maréchal des logis, major-général des logis; de là est venu le terme de logistique, qu’on emploie pour désigner ce qui se rapporte aux marches d’une armée.

Formerly the officers of the general staff were named: marshall of lodgings, major-general of lodgings; from there came the term of logistics [logistique], which we employ to designate those who are in charge of the functioning of an army.

The term is credited to Jomini, and the term and its etymology criticized by Georges de Chambray in 1832, writing:

Logistique: Ce mot me paraît être tout-à-fait nouveau, car je ne l'avais encore vu nulle part dans la littérature militaire. … il paraît le faire dériver du mot logis, étymologie singulière …

Logistic: This word appears to me to be completely new, as I have not yet seen it anywhere in military literature. … he appears to derive it from the word lodgings [logis], a peculiar etymology …

Chambray also notes that the term logistique was present in the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française as a synonym for algebra.

The French word: logistique is a homonym of the existing mathematical term, from Ancient Greek: λογῐστῐκός, romanized: logistikós, a traditional division of Greek mathematics; the mathematical term is presumably the origin of the term logistic in logistic growth and related terms. Some sources give this instead as the source of logistics, either ignorant of Jomini's statement that it was derived from logis, or dubious and instead believing it was in fact of Greek origin, or influenced by the existing term of Greek origin.

Definition

Jomini originally defined logistics as:

... l'art de bien ordonner les marches d'une armée, de bien combiner l'ordre des troupes dans les colonnes, les tems [temps] de leur départ, leur itinéraire, les moyens de communications nécessaires pour assurer leur arrivée à point nommé ...

... the art of well-ordering the functionings of an army, of well combining the order of troops in columns, the times of their departure, their itinerary, the means of communication necessary to assure their arrival at a named point ...

The Oxford English Dictionary defines logistics as "the branch of military science relating to procuring, maintaining and transporting material, personnel and facilities". However, the New Oxford American Dictionary defines logistics as "the detailed coordination of a complex operation involving many people, facilities, or supplies", and the Oxford Dictionary on-line defines it as "the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation". As such, logistics is commonly seen as a branch of engineering that creates "people systems" rather than "machine systems".

According to the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (previously the Council of Logistics Management), logistics is the process of planning, implementing and controlling procedures for the efficient and effective transportation and storage of goods including services and related information from the point of origin to the point of consumption for the purpose of conforming to customer requirements and includes inbound, outbound, internal and external movements.

Academics and practitioners traditionally refer to the terms operations or production management when referring to physical transformations taking place in a single business location (factory, restaurant or even bank clerking) and reserve the term logistics for activities related to distribution, that is, moving products on the territory. Managing a distribution center is seen, therefore, as pertaining to the realm of logistics since, while in theory, the products made by a factory are ready for consumption they still need to be moved along the distribution network according to some logic, and the distribution center aggregates and processes orders coming from different areas of the territory. That being said, from a modeling perspective, there are similarities between operations management and logistics, and companies sometimes use hybrid professionals, with for example a "Director of Operations" or a "Logistics Officer" working on similar problems. Furthermore, the term "supply chain management" originally referred to, among other issues, having an integrated vision of both production and logistics from point of origin to point of production. All these terms may suffer from semantic change as a side effect of advertising.

Logistics activities and fields

Inbound logistics is one of the primary processes of logistics concentrating on purchasing and arranging the inbound movement of materials, parts, or unfinished inventory from suppliers to manufacturing or assembly plants, warehouses, or retail stores.

Outbound logistics is the process related to the storage and movement of the final product and the related information flows from the end of the production line to the end user.

Given the services performed by logisticians, the main fields of logistics can be broken down as follows:

- Procurement logistics

- Distribution logistics

- After-sales logistics

- Disposal logistics

- Reverse logistics

- Green logistics

- Global logistics

- Domestics logistics

- Concierge service

- Reliability, availability, and maintainability

- Asset control logistics

- Point-of-sale material logistics

- Emergency logistics

- Production logistics

- Construction logistics

- Capital project logistics

- Digital logistics

- Humanitarian logistics

Procurement logistics consists of activities such as market research, requirements planning, make-or-buy decisions, supplier management, ordering, and order controlling. The targets in procurement logistics might be contradictory: maximizing efficiency by concentrating on core competences, outsourcing while maintaining the autonomy of the company, or minimizing procurement costs while maximizing security within the supply process.

Advance Logistics consists of the activities required to set up or establish a plan for logistics activities to occur.

Global Logistics is technically the process of managing the "flow" of goods through what is called a supply chain, from its place of production to other parts of the world. This often requires an intermodal transport system, transport via ocean, air, rail, and truck. The effectiveness of global logistics is measured in the Logistics Performance Index.

Distribution logistics has, as main tasks, the delivery of the finished products to the customer. It consists of order processing, warehousing, and transportation. Distribution logistics is necessary because the time, place, and quantity of production differ with the time, place, and quantity of consumption.

Disposal logistics has as its main function to reduce logistics cost(s) and enhance service(s) related to the disposal of waste produced during the operation of a business.

Reverse logistics denotes all those operations related to the reuse of products and materials. The reverse logistics process includes the management and the sale of surpluses, as well as products being returned to vendors from buyers. Reverse logistics stands for all operations related to the reuse of products and materials. It is "the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient, cost-effective flow of raw materials, in-process inventory, finished goods and related information from the point of consumption to the point of origin for the purpose of recapturing value or proper disposal. More precisely, reverse logistics is the process of moving goods from their typical final destination for the purpose of capturing value, or proper disposal. The opposite of reverse logistics is forward logistics."

Green Logistics describes all attempts to measure and minimize the ecological impact of logistics activities. This includes all activities of the forward and reverse flows. This can be achieved through intermodal freight transport, path optimization, vehicle saturation and city logistics.

RAM Logistics (see also Logistic engineering) combines both business logistics and military logistics since it is concerned with highly complicated technological systems for which Reliability, Availability and Maintainability are essential, ex: weapon systems and military supercomputers.

Asset Control Logistics: companies in the retail channels, both organized retailers and suppliers, often deploy assets required for the display, preservation, promotion of their products. Some examples are refrigerators, stands, display monitors, seasonal equipment, poster stands & frames.

Emergency logistics (or Humanitarian Logistics) is a term used by the logistics, supply chain, and manufacturing industries to denote specific time-critical modes of transport used to move goods or objects rapidly in the event of an emergency. The reason for enlisting emergency logistics services could be a production delay or anticipated production delay, or an urgent need for specialized equipment to prevent events such as aircraft being grounded (also known as "aircraft on ground"—AOG), ships being delayed, or telecommunications failure. Humanitarian logistics involves governments, the military, aid agencies, donors, non-governmental organizations and emergency logistics services are typically sourced from a specialist provider.

The term production logistics describes logistic processes within a value-adding system (ex: factory or a mine). Production logistics aims to ensure that each machine and workstation receives the right product in the right quantity and quality at the right time. The concern is with production, testing, transportation, storage, and supply. Production logistics can operate in existing as well as new plants: since manufacturing in an existing plant is a constantly changing process, machines are exchanged and new ones added, which gives the opportunity to improve the production logistics system accordingly. Production logistics provides the means to achieve customer response and capital efficiency. Production logistics becomes more important with decreasing batch sizes. In many industries (e.g. mobile phones), the short-term goal is a batch size of one, allowing even a single customer's demand to be fulfilled efficiently. Track and tracing, which is an essential part of production logistics due to product safety and reliability issues, is also gaining importance, especially in the automotive and medical industries.

Construction Logistics has been employed by civilizations for thousands of years. As the various human civilizations tried to build the best possible works of construction for living and protection. Now construction logistics has emerged as a vital part of construction. In the past few years, construction logistics has emerged as a different field of knowledge and study within the subject of supply chain management and logistics.

Military logistics

In military science, maintaining one's supply lines while disrupting those of the enemy is a crucial—some would say the most crucial—element of military strategy, since an armed force without resources and transportation is defenseless. The historical leaders Hannibal, Alexander the Great, and the Duke of Wellington are considered to have been logistical geniuses: Alexander's expedition benefited considerably from his meticulous attention to the provisioning of his army, Hannibal is credited to have "taught logistics" to the Romans during the Punic Wars and the success of the Anglo-Portuguese army in the Peninsula War was due to the effectiveness of Wellington's supply system, despite the numerical disadvantage. The defeat of the British in the American War of Independence and the defeat of the Axis in the African theater of World War II are attributed by some scholars to logistical failures.

Militaries have a significant need for logistics solutions and so have developed advanced implementations. Integrated Logistics Support (ILS) is a discipline used in military industries to ensure an easily supportable system with a robust customer service (logistic) concept at the lowest cost and in line with (often high) reliability, availability, maintainability, and other requirements, as defined for the project.

In military logistics, Logistics Officers manage how and when to move resources to the places they are needed.

Supply chain management in military logistics often deals with a number of variables in predicting cost, deterioration, consumption, and future demand. The United States Armed Forces' categorical supply classification was developed in such a way that categories of supply with similar consumption variables are grouped together for planning purposes. For instance, peacetime consumption of ammunition and fuel will be considerably lower than wartime consumption of these items, whereas other classes of supply such as subsistence and clothing have a relatively consistent consumption rate regardless of war or peace.

Some classes of supply have a linear demand relationship: as more troops are added, more supply items are needed; or as more equipment is used, more fuel and ammunition are consumed. Other classes of supply must consider a third variable besides usage and quantity: time. As equipment ages, more and more repair parts are needed over time, even when usage and quantity stay consistent. By recording and analyzing these trends over time and applying them to future scenarios, the US Armed Forces can accurately supply troops with the items necessary at the precise moment they are needed. History has shown that good logistical planning creates a lean and efficient fighting force. The lack thereof can lead to a clunky, slow, and ill-equipped force with too much or too little supply.

Business logistics

| Business logistics |

|---|

| Distribution methods |

| Management systems |

| Industry classification |

One definition of business logistics speaks of "having the right item in the right quantity at the right time at the right place for the right price in the right condition to the right customer". Business logistics incorporates all industry sectors and aims to manage the fruition of project life cycles, supply chains, and resultant efficiencies.

The term "business logistics" has evolved since the 1960s due to the increasing complexity of supplying businesses with materials and shipping out products in an increasingly globalized supply chain, leading to a call for professionals called "supply chain logisticians".

In business, logistics may have either an internal focus (inbound logistics) or an external focus (outbound logistics), covering the flow and storage of materials from point of origin to point of consumption (see supply-chain management). The main functions of a qualified logistician include inventory management, purchasing, transportation, warehousing, consultation, and the organizing and planning of these activities. Logisticians combine professional knowledge of each of these functions to coordinate resources in an organization.

There are two fundamentally different forms of logistics: One optimizes a steady flow of material through a network of transport links and storage nodes, while the other coordinates a sequence of resources to carry out some project (e.g., restructuring a warehouse).

Nodes of a distribution network

The nodes of a distribution network include:

- Factories where products are manufactured or assembled

- A depot or deposit, a standard type of warehouse for storing merchandise (high level of inventory)

- Distribution centers for order processing and order fulfillment (lower level of inventory) and also for receiving returning items from clients. Typically, distribution centers are way stations for products to be disbursed further down the supply chain. They usually do not ship inventory directly to customers, whereas fulfillment centers do.

- Transit points for cross docking activities, which consist of reassembling cargo units based on deliveries scheduled (only moving merchandise)

- Traditional “mom-and-pop” retail stores, modern supermarkets, hypermarkets, discount stores or also voluntary chains, consumers' co-operative, groups of consumer with collective buying power. Note that subsidiaries will be mostly owned by another company and franchisers, although using other company brands, actually own the point of sale.

There may be some intermediaries operating for representative matters between nodes such as sales agents or brokers.

Logistic families and metrics

A logistic family is a set of products that share a common characteristic: weight and volumetric characteristics, physical storing needs (temperature, radiation,...), handling needs, order frequency, package size, etc. The following metrics may be used by the company to organize its products in different families:

- Physical metrics used to evaluate inventory systems include stocking capacity, selectivity, superficial use, volumetric use, transport capacity, transport capacity use.

- Monetary metrics used include space holding costs (building, shelving, and services) and handling costs (people, handling machinery, energy, and maintenance).

Other metrics may present themselves in both physical or monetary form, such as the standard Inventory turnover.

Handling and order processing

Unit loads are combinations of individual items which are moved by handling systems, usually employing a pallet of normed dimensions.

Handling systems include: trans-pallet handlers, counterweight handler, retractable mast handler, bilateral handlers, trilateral handlers, AGV and other handlers.

Storage systems include: pile stocking, cell racks (either static or movable), cantilever racks and gravity racks.

Order processing is a sequential process involving: processing withdrawal list, picking (selective removal of items from loading units), sorting (assembling items based on the destination), package formation (weighting, labeling, and packing), order consolidation (gathering packages into loading units for transportation, control and bill of lading).

Picking can be both manual or automated. Manual picking can be both man to goods, i.e. operator using a cart or conveyor belt, or goods to man, i.e. the operator benefiting from the presence of a mini-load ASRS, vertical or horizontal carousel or from an Automatic Vertical Storage System (AVSS). Automatic picking is done either with dispensers or depalletizing robots.

Sorting can be done manually through carts or conveyor belts, or automatically through sorters.

Transportation

Cargo, i.e. merchandise being transported, can be moved through a variety of transportation means and is organized in different shipment categories. Unit loads are usually assembled into higher standardized units such as: ISO containers, swap bodies or semi-trailers. Especially for very long distances, product transportation will likely benefit from using different transportation means: multimodal transport, intermodal transport (no handling) and combined transport (minimal road transport). When moving cargo, typical constraints are maximum weight and volume.

Operators involved in transportation include: all train, road vehicles, boats, airplanes companies, couriers, freight forwarders and multi-modal transport operators.

Merchandise being transported internationally is usually subject to the Incoterms standards issued by the International Chamber of Commerce.

Configuration and management

Similarly to production systems, logistic systems need to be properly configured and managed. Actually a number of methodologies have been directly borrowed from operations management such as using Economic Order Quantity models for managing inventory in the nodes of the network. Distribution resource planning (DRP) is similar to MRP, except that it doesn't concern activities inside the nodes of the network but planning distribution when moving goods through the links of the network.

Traditionally in logistics configuration may be at the level of the warehouse (node) or at level of the distribution system (network).

Regarding a single warehouse, besides the issue of designing and building the warehouse, configuration means solving a number of interrelated technical-economic problems: dimensioning rack cells, choosing a palletizing method (manual or through robots), rack dimensioning and design, number of racks, number and typology of retrieval systems (e.g. stacker cranes). Some important constraints have to be satisfied: fork and load beams resistance to bending and proper placement of sprinklers. Although picking is more of a tactical planning decision than a configuration problem, it is important to take it into account when deciding the layout of the racks inside the warehouse and buying tools such as handlers and motorized carts since once those decisions are taken they will work as constraints when managing the warehouse, the same reasoning for sorting when designing the conveyor system or installing automatic dispensers.

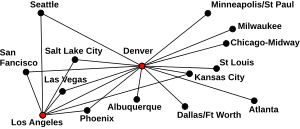

Configuration at the level of the distribution system concerns primarily the problem of location of the nodes in geographic space and distribution of capacity among the nodes. The first may be referred to as facility location (with the special case of site selection) while the latter to as capacity allocation. The problem of outsourcing typically arises at this level: the nodes of a supply chain are very rarely owned by a single enterprise. Distribution networks can be characterized by numbers of levels, namely the number of intermediary nodes between supplier and consumer:

- Direct store delivery, i.e. zero levels

- One level network: central warehouse

- Two level network: central and peripheral warehouses

This distinction is more useful for modeling purposes, but it relates also to a tactical decision regarding safety stocks: considering a two-level network, if safety inventory is kept only in peripheral warehouses then it is called a dependent system (from suppliers), if safety inventory is distributed among central and peripheral warehouses it is called an independent system (from suppliers). Transportation from producer to the second level is called primary transportation, from the second level to a consumer is called secondary transportation.

Although configuring a distribution network from zero is possible, logisticians usually have to deal with restructuring existing networks due to presence of an array of factors: changing demand, product or process innovation, opportunities for outsourcing, change of government policy toward trade barriers, innovation in transportation means (both vehicles or thoroughfares), the introduction of regulations (notably those regarding pollution) and availability of ICT supporting systems (e.g. ERP or e-commerce).

Once a logistic system is configured, management, meaning tactical decisions, takes place, once again, at the level of the warehouse and of the distribution network. Decisions have to be made under a set of constraints: internal, such as using the available infrastructure, or external, such as complying with the given product shelf lifes and expiration dates.

At the warehouse level, the logistician must decide how to distribute merchandise over the racks. Three basic situations are traditionally considered: shared storage, dedicated storage (rack space reserved for specific merchandise) and class-based storage (class meaning merchandise organized in different areas according to their access index).

Picking efficiency varies greatly depending on the situation. For a man to goods situation, a distinction is carried out between high-level picking (vertical component significant) and low-level picking (vertical component insignificant). A number of tactical decisions regarding picking must be made:

- Routing path: standard alternatives include transversal routing, return routing, midpoint routing, and largest gap return routing

- Replenishment method: standard alternatives include equal space supply for each product class and equal time supply for each product class.

- Picking logic: order picking vs batch picking

At the level of the distribution network, tactical decisions involve mainly inventory control and delivery path optimization. Note that the logistician may be required to manage the reverse flow along with the forward flow.

Warehouse management system and control

Although there is some overlap in functionality, warehouse management systems (WMS) can differ significantly from warehouse control systems (WCS). Simply put, a WMS plans a weekly activity forecast based on such factors as statistics and trends, whereas a WCS acts like a floor supervisor, working in real-time to get the job done by the most effective means. For instance, a WMS can tell the system that it is going to need five of stock-keeping unit (SKU) A and five of SKU B hours in advance, but by the time it acts, other considerations may have come into play or there could be a logjam on a conveyor. A WCS can prevent that problem by working in real-time and adapting to the situation by making a last-minute decision based on current activity and operational status. Working synergistically, WMS and WCS can resolve these issues and maximize efficiency for companies that rely on the effective operation of their warehouse or distribution center.

Logistics outsourcing

Logistics outsourcing involves a relationship between a company and an LSP (logistic service provider), which, compared with basic logistics services, has more customized offerings, encompasses a broad number of service activities, is characterized by a long-term orientation, and thus has a strategic nature.

Outsourcing does not have to be complete externalization to an LSP, but can also be partial:

- A single contract for supplying a specific service on occasion

- Creation of a spin-off

- Creation of a joint venture

Third-party logistics (3PL) involves using external organizations to execute logistics activities that have traditionally been performed within an organization itself. According to this definition, third-party logistics includes any form of outsourcing of logistics activities previously performed in house. For example, if a company with its own warehousing facilities decides to employ external transportation, this would be an example of third-party logistics. Logistics is an emerging business area in many countries. External 3PL providers have evolved from merely providing logistics capabilities to becoming real orchestrators of supply chains that create and sustain a competitive advantage, thus bringing about new levels of logistics outsourcing.

The concept of a fourth-party logistics (4PL) provider was first defined by Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) as an integrator that assembles the resources, planning capabilities, and technology of its own organization and other organizations to design, build, and run comprehensive supply chain solutions. Whereas a third-party logistics (3PL) service provider targets a single function, a 4PL targets management of the entire process. Some have described a 4PL as a general contractor that manages other 3PLs, truckers, forwarders, custom house agents, and others, essentially taking responsibility of a complete process for the customer.

Horizontal alliances between logistics service providers

Horizontal business alliances often occur between logistics service providers, i.e., the cooperation between two or more logistics companies that are potentially competing. In a horizontal alliance, these partners can benefit twofold. On one hand, they can "access tangible resources which are directly exploitable". In this example extending common transportation networks, their warehouse infrastructure and the ability to provide more complex service packages can be achieved by combining resources. On the other hand, partners can "access intangible resources, which are not directly exploitable". This typically includes know-how and information and, in turn, innovation.

Logistics automation

Logistics automation is the application of computer software or automated machinery to improve the efficiency of logistics operations. Typically, this refers to operations within a warehouse or distribution center with broader tasks undertaken by supply chain engineering systems and enterprise resource planning systems.

Industrial machinery can typically identify products through either barcode or RFID technologies. Information in traditional bar codes is stored as a sequence of black and white bars varying in width, which when read by laser is translated into a digital sequence, which according to fixed rules can be converted into a decimal number or other data. Sometimes information in a bar code can be transmitted through radio frequency, more typically radio transmission is used in RFID tags. An RFID tag is a card containing a memory chip and an antenna that transmits signals to a reader. RFID may be found on merchandise, animals, vehicles, and people as well.

Logistics: profession and organizations

A logistician is a professional logistics practitioner. Professional logisticians are often certified by professional associations. One can either work in a pure logistics company, such as a shipping line, airport, or freight forwarder, or within the logistics department of a company. However, as mentioned above, logistics is a broad field, encompassing procurement, production, distribution, and disposal activities. Hence, career perspectives are broad as well. A new trend in the industry is the 4PL, or fourth-party logistics, firms, consulting companies offering logistics services.

Some universities and academic institutions train students as logisticians, offering undergraduate and postgraduate programs. A university with a primary focus on logistics is Kühne Logistics University in Hamburg, Germany. It is non-profit and supported by Kühne-Foundation of the logistics entrepreneur Klaus Michael Kühne.

The Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (CILT), established in the United Kingdom in 1919, received a Royal Charter in 1926. The Chartered Institute is one of the professional bodies or institutions for the logistics and transport sectors that offer professional qualifications or degrees in logistics management. CILT programs can be studied at centers around the UK, some of which also offer distance learning options. The institute also have overseas branches namely The Chartered Institute of Logistics & Transport Australia (CILTA) in Australia and Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport in Hong Kong (CILTHK) in Hong Kong. In the UK, Logistics Management programs are conducted by many universities and professional bodies such as CILT. These programs are generally offered at the postgraduate level.

The Global Institute of Logistics established in New York in 2003 is a Think tank for the profession and is primarily concerned with intercontinental maritime logistics. It is particularly concerned with container logistics and the role of the seaport authority in the maritime logistics chain.

The International Association of Public Health Logisticians (IAPHL) is a professional network that promotes the professional development of supply chain managers and others working in the field of public health logistics and commodity security, with particular focus on developing countries. The association supports logisticians worldwide by providing a community of practice, where members can network, exchange ideas, and improve their professional skills.

Logistics museums

There are many museums in the world which cover various aspects of practical logistics. These include museums of transportation, customs, packing, and industry-based logistics. However, only the following museums are fully dedicated to logistics:

General logistics

- Logistics Museum (Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- Museum of Logistics (Tokyo, Japan)

- Beijing Wuzi University Logistics Museum (Beijing, China)

Military logistics

- Royal Logistic Corps Museum (Surrey, England, United Kingdom)

- The Canadian Forces Logistics Museum (Montreal, Quebec, Canada)

- Logistics Museum (Hanoi, Vietnam)