From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Rare Earth Hypothesis argues that planets with complex life, like

Earth, are exceptionally rare

In

planetary astronomy and

astrobiology, the

Rare Earth Hypothesis argues that the

origin of life and the

evolution of biological complexity such as

sexually reproducing,

multicellular organisms on

Earth (and, subsequently,

human intelligence) required an improbable combination of

astrophysical and

geological events and circumstances. According to the hypothesis, complex

extraterrestrial life is a very improbable phenomenon and likely to be extremely rare. The term "Rare Earth" originates from

Rare Earth: Why Complex Life Is Uncommon in the Universe (2000), a book by

Peter Ward, a geologist and paleontologist, and

Donald E. Brownlee, an astronomer and astrobiologist, both faculty members at the University of Washington.

A contrary view was argued in the 1970s and 1980s by

Carl Sagan and

Frank Drake, among others. It holds that Earth is a typical rocky

planet in a typical

planetary system, located in a non-exceptional region of a common

barred-spiral galaxy. Given the

principle of mediocrity (in the same vein as the

Copernican principle),

it is probable that we are typical, and the universe teems with complex

life. However, Ward and Brownlee argue that planets, planetary systems,

and galactic regions that are as friendly to complex life as the Earth,

the

Solar System, and our

galactic region are very rare.

Requirements for complex life

The Rare Earth hypothesis argues that the

evolution of biological complexity requires a host of fortuitous circumstances, such as a

galactic habitable zone, a central star and planetary system having the requisite character, the

circumstellar habitable zone, a right-sized terrestrial planet, the advantage of a gas giant guardian like Jupiter and a large

natural satellite, conditions needed to ensure the planet has a

magnetosphere and

plate tectonics, the chemistry of the

lithosphere,

atmosphere, and oceans, the role of "evolutionary pumps" such as massive

glaciation and rare

bolide impacts, and whatever led to the appearance of the

eukaryote cell,

sexual reproduction and the

Cambrian explosion of

animal,

plant, and

fungi phyla. The

evolution of human intelligence may have required yet further events, which are extremely unlikely to have happened were it not for the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago removing

dinosaurs as the dominant terrestrial

vertebrates.

In order for a small rocky planet to support complex life, Ward and

Brownlee argue, the values of several variables must fall within narrow

ranges. The

universe

is so vast that it could contain many Earth-like planets. But if such

planets exist, they are likely to be separated from each other by many

thousands of

light years. Such distances may preclude communication among any intelligent species evolving on such planets, which would solve the

Fermi paradox: "If extraterrestrial aliens are common, why aren't they obvious?"

[1]

The right location in the right kind of galaxy

Rare Earth

suggests that much of the known universe, including large parts of our

galaxy, are "dead zones" unable to support complex life. Those parts of a

galaxy where complex life is possible make up the

galactic habitable zone, primarily characterized by distance from the

Galactic Center. As that distance increases:

- Star metallicity declines. Metals (which in astronomy means all elements other than hydrogen and helium) are necessary to the formation of terrestrial planets.

- The X-ray and gamma ray radiation from the black hole at the galactic center, and from nearby neutron stars, becomes less intense. Thus the early universe, and present-day galactic regions where stellar density is high and supernovae are common, will be dead zones.[2]

- Gravitational perturbation of planets and planetesimals

by nearby stars becomes less likely as the density of stars decreases.

Hence the further a planet lies from the Galactic Center or a spiral

arm, the less likely it is to be struck by a large bolide which could extinguish all complex life on a planet.

Dense center of galaxies such as

NGC 7331 (often referred to as a "twin" of the

Milky Way[3]) have high radiation levels toxic to complex life.

According to Rare Earth, globular clusters are unlikely to support life.

Item #1 rules out the outer reaches of a galaxy; #2 and #3 rule out

galactic inner regions. Hence a galaxy's habitable zone may be a ring

sandwiched between its uninhabitable center and outer reaches.

Also, a habitable planetary system must maintain its favorable location long enough for complex life to evolve. A star with an

eccentric

(elliptic or hyperbolic) galactic orbit will pass through some spiral

arms, unfavorable regions of high star density; thus a life-bearing star

must have a galactic orbit that is nearly circular, with a close

synchronization between the orbital velocity of the star and of the

spiral arms. This further restricts the galactic habitable zone within a

fairly narrow range of distances from the Galactic Center. Lineweaver

et al.

[4] calculate this zone to be a ring 7 to 9

kiloparsecs in radius, including no more than 10% of the stars in the

Milky Way,

[5] about 20 to 40 billion stars. Gonzalez, et al.

[6] would halve these numbers; they estimate that at most 5% of stars in the Milky Way fall in the galactic habitable zone.

Approximately 77% of observed galaxies are spiral,

[7] two-thirds of all spiral galaxies are barred, and more than half, like the Milky Way, exhibit multiple arms.

[8] According to Rare Earth, our own galaxy is unusually quiet and dim (see below), representing just 7% of its kind.

[9] Even so, this would still represent more than 200 billion galaxies in the known universe.

Our galaxy also appears unusually favorable in suffering fewer

collisions with other galaxies over the last 10 billion years, which can

cause more supernovae and other disturbances.

[10] Also, the Milky Way's central

black hole seems to have neither too much nor too little activity.

[11]

The orbit of the Sun around the center of the Milky Way is indeed almost perfectly circular, with

a period of 226 Ma

(million years), closely matching the rotational period of the galaxy.

However, the majority of stars in barred spiral galaxies populate the

spiral arms rather than the halo and tend to move in

gravitationally aligned orbits,

so there is little that is unusual about the Sun's orbit. While the

Rare Earth hypothesis predicts that the Sun should rarely, if ever, have

passed through a spiral arm since its formation, astronomer Karen

Masters has calculated that the orbit of the Sun takes it through a

major spiral arm approximately every 100 million years.

[12] Some researchers have suggested that several mass extinctions do correspond with previous crossings of the spiral arms.

[13]

Orbiting at the right distance from the right type of star

According to the hypothesis, Earth has an improbable orbit in the very narrow habitable zone (dark green) around the Sun.

The terrestrial example suggests that complex life requires liquid

water, requiring an orbital distance neither too close nor too far from

the central star, another scale of

habitable zone or

Goldilocks Principle:

[14] The habitable zone varies with the star's type and age.

For advanced life, the star must also be highly stable, which is

typical of middle star life, about 4.6 billion years old. Proper

metallicity and size are also very important to stability. The Sun has a low 0.1%

luminosity variation. To date no

solar twin

star twin, with an exact match of the sun's luminosity variation, has

been found, though some come close. The star must have no stellar

companions, as in

binary systems, which would disrupt the orbits of planets. Estimates suggest 50% or more of all star systems are binary.

[15][16][17][18]

The habitable zone for a main sequence star very gradually moves out

over its lifespan until it becomes a white dwarf and the habitable zone

vanishes.

The liquid water and other gases available in the habitable zone bring the benefit of

greenhouse warming. Even though the

Earth's atmosphere

contains a water vapor concentration from 0% (in arid regions) to 4%

(in rain forest and ocean regions) and – as of February 2018 – only

408.05

[citation needed] parts per million of CO

2, these small amounts suffice to raise the average surface temperature by about 40 °C,

[19]

with the dominant contribution being due to water vapor, which together

with clouds makes up between 66% and 85% of Earth's greenhouse effect,

with CO

2 contributing between 9% and 26% of the effect.

[20]

Rocky planets must orbit within the habitable zone for life to form. Although the habitable zone of such hot stars as

Sirius or

Vega is wide, hot stars also emit much more

ultraviolet radiation that

ionizes any planetary

atmosphere. They may become

red giants before advanced life

evolves on their planets. These considerations rule out the massive and powerful stars of type F6 to O (see

stellar classification) as homes to evolved

metazoan life.

Small

red dwarf stars conversely have small

habitable zones wherein planets are in

tidal lock,

with one very hot side always facing the star and another very cold

side; and they are also at increased risk of solar flares (see

Aurelia).

Life therefore cannot arise in such systems. Rare Earth proponents

claim that only stars from F7 to K1 types are hospitable. Such stars are

rare: G type stars such as the Sun (between the hotter F and cooler K)

comprise only 9%

[21] of the hydrogen-burning stars in the Milky Way.

Such aged stars as

red giants and

white dwarfs are also unlikely to support life. Red giants are common in globular clusters and

elliptical galaxies.

White dwarfs are mostly dying stars that have already completed their

red giant phase. Stars that become red giants expand into or overheat

the habitable zones of their youth and middle age (though theoretically

planets at a much greater distance

may become habitable).

An energy output that varies with the lifetime of the star will very likely prevent life (e.g., as

Cepheid variables).

A sudden decrease, even if brief, may freeze the water of orbiting

planets, and a significant increase may evaporate it and cause a

greenhouse effect that prevents the oceans from reforming.

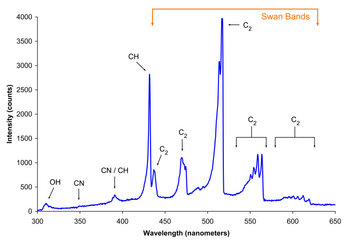

All known life requires the complex chemistry of

metallic elements. The

absorption spectrum

of a star reveals the presence of metals within, and studies of stellar

spectra reveal that many, perhaps most, stars are poor in metals.

Because heavy metals originate in

supernova

explosions, metallicity increases in the universe over time. Low

metallicity characterizes the early universe: globular clusters and

other stars that formed when the universe was young, stars in most

galaxies other than large

spirals,

and stars in the outer regions of all galaxies. Metal-rich central

stars capable of supporting complex life are therefore believed to be

most common in the quiet suburbs

[vague] of the larger spiral galaxies—where radiation also happens to be weak.

[22]

With the right arrangement of planets

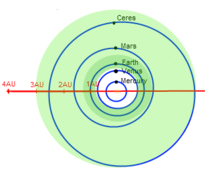

Depiction of the Sun and planets of the Solar System and the sequence of

planets. Rare Earth argues that without such an arrangement, in

particular the presence of the massive gas giant Jupiter (fifth planet

from the Sun and the largest), complex life on Earth would not have

arisen.

Rare Earth proponents argue that a planetary system capable of

sustaining complex life must be structured more or less like the Solar

System, with small and rocky inner planets and outer gas giants.

[23]

Without the protection of 'celestial vacuum cleaner' planets with

strong gravitational pull, a planet would be subject to more

catastrophic asteroid collisions.

Observations of exo-planets have shown that arrangements of planets

similar to our Solar System are rare. Most planetary systems have super

Earths, several times larger than Earth, close to their star, whereas

our Solar System's inner region has only a few small rocky planets and

none inside Mercury's orbit. Only 10% of stars have giant planets

similar to Jupiter and Saturn, and those few rarely have stable nearly

circular orbits distant from their star.

Konstantin Batygin

and colleagues argue that these features can be explained if, early in

the history of the Solar System, Jupiter and Saturn drifted towards the

Sun, sending showers of planetesimals towards the super-Earths which

sent them spiralling into the Sun, and ferrying icy building blocks into

the terrestrial region of the Solar System which provided the building

blocks for the rocky planets. The two giant planets then drifted out

again to their present position. However, in the view of Batygin and his

colleagues: "The concatenation of chance events required for this

delicate choreography suggest that small, Earth-like rocky planets – and

perhaps life itself – could be rare throughout the cosmos."

[24]

A continuously stable orbit

Rare

Earth argues that a gas giant must not be too close to a body where

life is developing. Close placement of gas giant(s) could disrupt the

orbit of a potential life-bearing planet, either directly or by drifting

into the habitable zone.

Newtonian dynamics can produce

chaotic planetary orbits, especially in a system having

large planets at high

orbital eccentricity.

[25]

The need for stable orbits rules out

stars with systems of planets that contain large planets with orbits close to the host star (called "

hot Jupiters").

It is believed that hot Jupiters have migrated inwards to their current

orbits. In the process, they would have catastrophically disrupted the

orbits of any planets in the habitable zone.

[26] To exacerbate matters, hot Jupiters are much more common orbiting F and G class stars.

[27]

A terrestrial planet of the right size

Planets of the Solar System to scale. Rare Earth argues that complex

life cannot exist on large gaseous planets like Jupiter and Saturn (top

row) or Uranus and Neptune (top middle) or smaller planets such as Mars

and Mercury

It is argued that life requires terrestrial planets like Earth and as

gas giants lack such a surface, that complex life cannot arise there.

[28]

A planet that is too small cannot hold much atmosphere, making

surface temperature low and variable and oceans impossible. A small

planet will also tend to have a rough surface, with large mountains and

deep canyons. The core will cool faster, and

plate tectonics may be brief or entirely absent. A planet that is too large will retain too dense atmosphere like

Venus.

Although Venus is similar in size and mass to Earth, its surface

atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of Earth, and surface temperature

of 735 K (462 °C; 863 °F). Earth had a similar early atmosphere to

Venus, but may have lost it in the

giant impact event.

[29]

With plate tectonics

The

Great American Interchange on Earth, around ~ 3.5 to 3 Ma, an example of species competition, resulting from continental plate interaction.

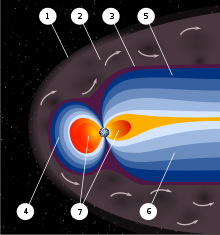

An artist's rendering of the structure of Earth's magnetic field-magnetosphere that protects Earth's life from

solar radiation.

1) Bow shock. 2) Magnetosheath. 3) Magnetopause. 4) Magnetosphere.

5) Northern tail lobe. 6) Southern tail lobe. 7) Plasmasphere.

Rare Earth proponents argue that

plate tectonics and a strong

magnetic field are essential for

biodiversity,

global temperature regulation, and the

carbon cycle.

[30] The lack of

mountain chains

elsewhere in the Solar System is direct evidence that Earth is the only

body with plate tectonics, and thus the only nearby body capable of

supporting life.

[31]

Plate tectonics depend on the right chemical composition and a long-lasting source of heat from

radioactive decay. Continents must be made of less dense

felsic rocks that "float" on underlying denser

mafic rock. Taylor

[32] emphasizes that tectonic

subduction zones require the lubrication of oceans of water. Plate tectonics also provides a means of

biochemical cycling.

[33]

Plate tectonics and as a result

continental drift and the creation of separate land masses would create diversified

ecosystems and

biodiversity, one of the strongest defences against extinction.

[34] An example of species diversification and later competition on Earth's continents is the

Great American Interchange. North and Middle America drifted into

South America at around 3.5 to 3 Ma. The

fauna of South America evolved separately for about 30 million years, since

Antarctica separated. Many species were subsequently wiped out in mainly South America by competing

Northern American animals.

A large moon

Tide pools resulting from tidal interaction of the Moon are said to have promoted the evolution of complex life.

The Moon is unusual because the other rocky planets in the Solar System either have no satellites (

Mercury and

Venus), or only tiny satellites which are probably captured asteroids (

Mars).

The

Giant-impact theory hypothesizes that the Moon resulted from the impact of a

Mars-sized body, dubbed

Theia, with the very young Earth. This giant impact also gave the Earth its

axial tilt (inclination) and velocity of rotation.

[32] Rapid rotation reduces the daily variation in temperature and makes

photosynthesis viable.

[35] The

Rare Earth hypothesis further argues that the axial tilt cannot be too large or too small (relative to the

orbital plane).

A planet with a large tilt will experience extreme seasonal variations

in climate. A planet with little or no tilt will lack the stimulus to

evolution that climate variation provides.

[citation needed]

In this view, the Earth's tilt is "just right". The gravity of a large

satellite also stabilizes the planet's tilt; without this effect the

variation in tilt would be

chaotic, probably making complex life forms on land impossible.

[36]

If the Earth had no Moon, the ocean

tides resulting solely from the Sun's gravity would be only half that of the lunar tides. A large satellite gives rise to

tidal pools, which may be essential for the formation of

complex life, though this is far from certain.

[37]

A large satellite also increases the likelihood of

plate tectonics through the effect of

tidal forces on the planet's crust.

[citation needed] The impact that formed the Moon may also have initiated plate tectonics, without which the

continental crust would cover the entire planet, leaving no room for

oceanic crust.

[citation needed] It is possible that the large scale

mantle convection needed to drive plate tectonics could not have emerged in the absence of crustal inhomogeneity.

Atmosphere

A

terrestrial planet of the right size is needed to retain an atmosphere,

like Earth and Venus. On Earth, once the giant impact of

Theia thinned

Earth's atmosphere, other events were needed to make the atmosphere capable of sustaining life. The

Late Heavy Bombardment reseeded Earth with water lost after the impact of Theia.

[38] The development of an

ozone layer formed protection from

ultraviolet (UV) sunlight.

[39][40] Nitrogen and

carbon dioxide are needed in a correct ratio for life to form.

[41] Lightning is needed for

nitrogen fixation.

[42][42] The carbon dioxide

gas needed for life comes from sources such as

volcanoes and

geysers. Carbon dioxide is only needed at low levels

[citation needed] (currently at 400

ppm); at high levels it is poisonous.

[43][44] Precipitation is needed to have a stable water cycle.

[45] A proper atmosphere must reduce

diurnal temperature variation.

[46][47]

One or more evolutionary triggers for complex life

This diagram illustrates the twofold cost of sex. If each individual were to contribute to the same number of offspring (two), (a) the sexual population remains the same size each generation, where the (b) asexual population doubles in size each generation

Regardless of whether planets with similar physical attributes to the

Earth are rare or not, some argue that life usually remains simple

bacteria. Biochemist

Nick Lane argues that simple cells (

prokaryotes)

emerged soon after Earth's formation, but since almost half the

planet's life had passed before they evolved into complex ones (

eukaryotes) all of whom share a

common ancestor, this event can only have happened once. In some views,

prokaryotes

lack the cellular architecture to evolve into eukaryotes because a

bacterium expanded up to eukaryotic proportions would have tens of

thousands of times less energy available; two billion years ago, one

simple cell incorporated itself into another, multiplied, and evolved

into

mitochondria

that supplied the vast increase in available energy that enabled the

evolution of complex life. If this incorporation occurred only once in

four billion years or is otherwise unlikely, then life on most planets

remains simple.

[48]

An alternative view is that mitochondria evolution was environmentally

triggered, and that mitochondria-containing organisms appeared very soon

after the first traces of atmospheric oxygen.

[49]

The evolution and persistence of

sexual reproduction is another mystery in biology. The purpose of

sexual reproduction is unclear, as in many organisms it has a 50% cost (fitness disadvantage) in relation to

asexual reproduction.

[50] Mating types (types of

gametes, according to their compatibility) may have arisen as a result of

anisogamy (gamete dimorphism), or the male and female genders may have evolved before anisogamy.

[51][52] It is also unknown why most sexual organisms use a binary

mating system,

[53] and why some organisms have gamete dimorphism.

Charles Darwin was the first to suggest that

sexual selection drives

speciation; without it, complex life would probably not have evolved.

The right time in evolution

Timeline of evolution;

human writings exists for only 0.000218% of Earth's history.

While life on Earth is regarded to have spawned relatively early in

the planet's history, the evolution from multicellular to intelligent

organisms took around 800 million years.

[54]

Civilizations on Earth have existed for about 12,000 years and radio

communication reaching space has existed for less than 100 years.

Relative to the age of the Solar System (~4.57 Ga) this is a short time,

in which extreme climatic variations, super volcanoes, and large

meteorite impacts were absent. These events would severely harm

intelligent life, as well as life in general. For example, the

Permian-Triassic mass extinction,

caused by widespread and continuous volcanic eruptions in an area the

size of Western Europe, led to the extinction of 95% of known species

around 251.2

Ma ago. About 65 million years ago, the

Chicxulub impact at the

Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (~65.5 Ma) on the

Yucatán peninsula in

Mexico led to a mass extinction of the most advanced species at that time.

If there were intelligent extraterrestrial civilizations able to make

contact with distant Earth, they would have to live in the same 12Ka

period of the 800Ma evolution of life.

Rare Earth equation

The following discussion is adapted from Cramer.

[55] The Rare Earth equation is Ward and Brownlee's

riposte to the

Drake equation. It calculates

, the number of Earth-like planets in the Milky Way having complex life forms, as:

According to Rare Earth, the Cambrian explosion that saw extreme diversification of

chordata from simple forms like Pikaia (pictured) was an improbable event

[56]

[56]

where:

- N* is the number of stars in the Milky Way.

This number is not well-estimated, because the Milky Way's mass is not

well estimated, with little information about the number of very small

stars. N* is at least 100 billion, and may be as high as 500 billion, if there are many low visibility stars.

is the average number of planets in a star's habitable zone. This zone

is fairly narrow, because constrained by the requirement that the

average planetary temperature be consistent with water remaining liquid

throughout the time required for complex life to evolve. Thus

is the average number of planets in a star's habitable zone. This zone

is fairly narrow, because constrained by the requirement that the

average planetary temperature be consistent with water remaining liquid

throughout the time required for complex life to evolve. Thus  =1 is a likely upper bound.

=1 is a likely upper bound.

We assume

.

The Rare Earth hypothesis can then be viewed as asserting that the

product of the other nine Rare Earth equation factors listed below,

which are all fractions, is no greater than 10

−10 and could plausibly be as small as 10

−12. In the latter case,

could be as small as 0 or 1. Ward and Brownlee do not actually calculate the value of

,

because the numerical values of quite a few of the factors below can

only be conjectured. They cannot be estimated simply because

we have but one data point: the Earth, a rocky planet orbiting a

G2 star in a quiet suburb of a large

barred spiral galaxy, and the home of the only intelligent species we know, namely ourselves.

is the fraction of stars in the galactic habitable zone (Ward, Brownlee, and Gonzalez estimate this factor as 0.1[6]).

is the fraction of stars in the galactic habitable zone (Ward, Brownlee, and Gonzalez estimate this factor as 0.1[6]). is the fraction of stars in the Milky Way with planets.

is the fraction of stars in the Milky Way with planets. is the fraction of planets that are rocky ("metallic") rather than gaseous.

is the fraction of planets that are rocky ("metallic") rather than gaseous. is the fraction of habitable planets where microbial life arises. Ward

and Brownlee believe this fraction is unlikely to be small.

is the fraction of habitable planets where microbial life arises. Ward

and Brownlee believe this fraction is unlikely to be small. is the fraction of planets where complex life evolves. For 80% of the

time since microbial life first appeared on the Earth, there was only

bacterial life. Hence Ward and Brownlee argue that this fraction may be

very small.

is the fraction of planets where complex life evolves. For 80% of the

time since microbial life first appeared on the Earth, there was only

bacterial life. Hence Ward and Brownlee argue that this fraction may be

very small. is the fraction of the total lifespan of a planet during which complex

life is present. Complex life cannot endure indefinitely, because the

energy put out by the sort of star that allows complex life to emerge

gradually rises, and the central star eventually becomes a red giant,

engulfing all planets in the planetary habitable zone. Also, given

enough time, a catastrophic extinction of all complex life becomes ever

more likely.

is the fraction of the total lifespan of a planet during which complex

life is present. Complex life cannot endure indefinitely, because the

energy put out by the sort of star that allows complex life to emerge

gradually rises, and the central star eventually becomes a red giant,

engulfing all planets in the planetary habitable zone. Also, given

enough time, a catastrophic extinction of all complex life becomes ever

more likely. is the fraction of habitable planets with a large moon. If the giant impact theory of the Moon's origin is correct, this fraction is small.

is the fraction of habitable planets with a large moon. If the giant impact theory of the Moon's origin is correct, this fraction is small. is the fraction of planetary systems with large Jovian planets. This fraction could be large.

is the fraction of planetary systems with large Jovian planets. This fraction could be large. is the fraction of planets with a sufficiently low number of extinction

events. Ward and Brownlee argue that the low number of such events the

Earth has experienced since the Cambrian explosion may be unusual, in which case this fraction would be small.

is the fraction of planets with a sufficiently low number of extinction

events. Ward and Brownlee argue that the low number of such events the

Earth has experienced since the Cambrian explosion may be unusual, in which case this fraction would be small.

The Rare Earth equation, unlike the

Drake equation, does not factor the probability that complex life evolves into

intelligent life that discovers technology (Ward and Brownlee are not

evolutionary biologists). Barrow and Tipler

[57] review the consensus among such biologists that the evolutionary path from primitive Cambrian

chordates, e.g.,

Pikaia to

Homo sapiens, was a highly improbable event. For example, the large

brains of humans have marked adaptive disadvantages, requiring as they do an expensive

metabolism, a long

gestation period, and a childhood lasting more than 25% of the average total life span. Other improbable features of humans include:

- Being one of a handful of extant bipedal land (non-avian) vertebrate. Combined with an unusual eye–hand coordination, this permits dextrous manipulations of the physical environment with the hands;

- A vocal apparatus far more expressive[citation needed] than that of any other mammal, enabling speech. Speech makes it possible for humans to interact cooperatively, to share knowledge, and to acquire a culture;

- The capability of formulating abstractions to a degree permitting the invention of mathematics, and the discovery of science and technology. Only recently did humans acquire anything like their current scientific and technological sophistication.

Advocates

Writers who support the Rare Earth hypothesis:

- Stuart Ross Taylor,[32]

a specialist on the Solar System, firmly believes in the hypothesis.

Taylor concludes that the Solar System is probably very unusual, because

it resulted from so many chance factors and events.

- Stephen Webb,[1] a physicist, mainly presents and rejects candidate solutions for the Fermi paradox. The Rare Earth hypothesis emerges as one of the few solutions left standing by the end of the book.

- Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist, endorses the Rare Earth hypothesis in chapter 5 of his Life's Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe,[58] and cites Ward and Brownlee's book with approval.[59]

- John D. Barrow and Frank J. Tipler (1986. 3.2, 8.7, 9), cosmologists, vigorously defend the hypothesis that humans are likely to be the only intelligent life in the Milky Way, and perhaps the entire universe. But this hypothesis is not central to their book The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, a thorough study of the anthropic principle and of how the laws of physics are peculiarly suited to enable the emergence of complexity in nature.

- Ray Kurzweil, a computer pioneer and self-proclaimed Singularitarian, argues in The Singularity Is Near that the coming Singularity

requires that Earth be the first planet on which sentient,

technology-using life evolved. Although other Earth-like planets could

exist, Earth must be the most evolutionarily advanced, because otherwise

we would have seen evidence that another culture had experienced the Singularity and expanded to harness the full computational capacity of the physical universe.

- John Gribbin, a prolific science writer, defends the hypothesis in Alone in the Universe: Why our planet is unique.[60]

- Guillermo Gonzalez, astrophysicist who coined the term galactic habitable zone uses the hypothesis in his book The Privileged Planet to promote the concept of intelligent design.[61]

- Michael H. Hart, astrophysicist

who proposed a very narrow habitable zone based on climate studies,

edited the influential book "Extraterrestrials: Where are They" and

authored one of its chapters "Atmospheric Evolution, the Drake Equation

and DNA: Sparse Life in an Infinite Universe".[62]

- Howard Alan Smith,

astrophysicist and author of 'Let there be light: modern cosmology and

Kabbalah: a new conversation between science and religion'.[63]

- Marc J. Defant, professor of geochemistry and volcanology,

elaborated on several aspects of the rare earth hypothesis in his TEDx

talk entitled: Why We are Alone in the Galaxy.[64]

Criticism

Cases against the Rare Earth Hypothesis take various forms.

Anthropic reasoning

The

hypothesis concludes, more or less, that complex life is rare because

it can evolve only on the surface of an Earth-like planet or on a

suitable satellite of a planet. Some biologists, such as

Jack Cohen, believe this assumption too restrictive and unimaginative; they see it as a form of

circular reasoning.

According to

David Darling, the Rare Earth hypothesis is neither

hypothesis nor

prediction, but merely a description of how life arose on Earth.

[65] In his view Ward and Brownlee have done nothing more than select the factors that best suit their case.

What matters is not whether there's anything unusual about the Earth; there's going to be something idiosyncratic

about every planet in space. What matters is whether any of Earth's

circumstances are not only unusual but also essential for complex life.

So far we've seen nothing to suggest there is.[66]

Critics also argue that there is a link between the Rare Earth Hypothesis and the

creationist ideas of

intelligent design.

[67]

Exoplanets around main sequence stars are being discovered in large numbers

An increasing number of

extrasolar planet discoveries are being made with 3,786 planets in 2,834 planetary systems known as of 2 June 2018.

[68] Rare Earth proponents argue life cannot arise outside Sun-like systems. However,

some exobiologists have suggested that stars outside this range may give

rise to life

under the right circumstances; this possibility is a central point of

contention to the theory because these late-K and M category stars make

up about 82% of all hydrogen-burning stars.

[21]

Current technology limits the testing of important Rare Earth criteria: surface water, tectonic plates, a large moon and

biosignatures

are currently undetectable. Though planets the size of Earth are

difficult to detect and classify, scientists now think that rocky

planets are common around Sun-like stars.

[69] The

Earth Similarity Index (ESI) of mass, radius and temperature provides a means of measurement, but falls short of the full Rare Earth criteria.

[70][71]

Rocky planets orbiting within habitable zones may not be rare

Some argue that Rare Earth's estimates of rocky planets in habitable zones (

in the Rare Earth equation) are too restrictive.

James Kasting cites the

Titius-Bode law

to contend that it is a misnomer to describe habitable zones as narrow

when there is a 50% chance of at least one planet orbiting within one.

[73]

In 2013 a study that was published in the journal Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences calculated that about "one in five" of all

sun-like

stars are expected to have earthlike planets "within the

habitable zones of their stars"; 8.8 billion of them therefore exist in the Milky Way galaxy alone.

[74] On 4 November 2013, astronomers reported, based on

Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion

Earth-sized planets orbiting in the

habitable zones of

sun-like stars and

red dwarf stars within the

Milky Way Galaxy.

[75][76] 11 billion of these estimated planets may be orbiting sun-like stars.

[77]

Uncertainty over Jupiter's role

The requirement for a system to have a Jovian planet as protector (Rare Earth equation factor

) has been challenged, affecting the number of proposed extinction events (Rare Earth equation factor

). Kasting's 2001 review of Rare Earth questions whether a Jupiter protector has any bearing on the incidence of complex life.

[78] Computer modelling including the 2005

Nice model and 2007

Nice 2 model yield inconclusive results in relation to Jupiter's gravitational influence and impacts on the inner planets.

[79]

A study by Horner and Jones (2008) using computer simulation found that

while the total effect on all orbital bodies within the Solar System is

unclear, Jupiter has caused more impacts on Earth than it has

prevented.

[80] Lexell's Comet,

a 1770 near miss that passed closer to Earth than any other comet in

recorded history, was known to be caused by the gravitational influence

of Jupiter.

[81] Grazier (2017) claims that the idea of Jupiter as a shield is a misinterpretation of a 1996 study by

George Wetherill,

and using computer models Grazier was able to demonstrate that Saturn

protects Earth from more asteroids and comets than does Jupiter.

[82]

Plate tectonics may not be unique to Earth or a requirement for complex life

Geological discoveries like the active features of Pluto's

Tombaugh Regio appear to contradict the argument that geologically active worlds like Earth are rare.

[83]

Ward and Brownlee argue that

tectonics is necessary to support

biogeochemical cycles

required for complex life, and predicted that such geological features

would not be found outside of Earth, pointing to a lack of observable

mountain ranges and

subduction.

[84]

There is, however, no scientific consensus on the evolution of plate

tectonics on Earth. Though it is believed that tectonic motion first

began around three billion years ago,

[85]

by this time photosynthesis and oxygenation had already begun.

Furthermore, recent studies point to plate tectonics as an episodic

planetary phenomenon, and that life may evolve during periods of

"stagnant-lid" rather than plate tectonic states.

[86]

Recent evidence also points to similar activity either having occurred or continuing to occur elsewhere. The

geology of Pluto, for example, described by Ward and Brownlee as "without mountains or volcanoes ... devoid of volcanic activity",

[22] has since been found to be quite the contrary, with a geologically active surface possessing organic molecules

[87] and mountain ranges

[88] like

Tenzing Montes and

Hillary Montes comparable in relative size to those of Earth, and observations suggest the involvement of endogenic processes.

[89] Plate tectonics has been suggested as a hypothesis for the

Martian dichotomy, and in 2012 geologist An Yin put forward evidence for active plate tectonics on Mars.

[90] Europa has long been suspected to have plate tectonics

[91] and in 2014 NASA announced evidence of active subduction.

[92] In 2017, scientists studying the

Geology of Charon confirmed that icy plate tectonics also operated on Pluto's largest moon.

[93]

Kasting suggests that there is nothing unusual about the occurrence

of plate tectonics in large rocky planets and liquid water on the

surface as most should generate internal heat even without the

assistance of radioactive elements.

[78] Studies by Valencia

[94] and Cowan

[95] suggest that plate tectonics may be inevitable for terrestrial planets Earth sized or larger, that is,

Super-Earths, which are now known to be more common in planetary systems.

[96]

Free oxygen may neither be rare nor a prerequisite for multicellular life

Animals like

Spinoloricus nov. sp. appear to defy the premise that animal life would not exist without oxygen

The hypothesis that

molecular oxygen, necessary for

animal life, is rare and that a

Great Oxygenation Event (Rare Earth equation factor

) could only have been triggered and sustained by tectonics, appears to have been invalidated by more recent discoveries.

Ward and Brownlee ask "whether oxygenation, and hence the rise of

animals, would ever have occurred on a world where there were no

continents to erode".

[97] Extraterrestrial free oxygen has recently been detected around other solid objects, including Mercury,

[98] Venus,

[99] Mars

[100] Jupiter's four

Galilean moons,

[101] Saturn's moons Enceladus,

[102] Dione

[103][104] and Rhea

[105] and even the atmosphere of a comet.

[106]

This has led scientists to speculate whether processes other than

photosynthesis could be capable of generating an environment rich in

free oxygen. Wordsworth (2014) concludes that oxygen generated other

than through

photodissociation may be likely on Earth-like exoplanets, and could actually lead to false positive detections of life.

[107] Narita (2015) suggests

photocatalysis by

titanium dioxide as a geochemical mechanism for producing oxygen atmospheres.

[108]

Since Ward & Brownlee's assertion that "there is irrefutable

evidence that oxygen is a necessary ingredient for animal life",

[97] anaerobic metazoa have been found that indeed do metabolise without oxygen.

Spinoloricus nov. sp., for example, a species discovered in the

hypersaline anoxic L'Atalante basin at the bottom of the

Mediterranean Sea in 2010, appears to metabolise with hydrogen, lacking

mitochondria and instead using

hydrogenosomes.

[109][110] Stevenson (2015) has proposed other membrane alternatives for complex life in worlds without oxygen.

[111] In 2017, scientists from the

NASA Astrobiology Institute discovered the necessary chemical preconditions for the formation of

azotosomes on Saturn's moon Titan, a world that lacks atmospheric oxygen.

[112]

Independent studies by Schirrmeister and by Mills concluded that

Earth's multicellular life existed prior to the Great Oxygenation Event,

not as a consequence of it.

[113][114]

NASA scientists Hartman and McKay argue that plate tectonics may in

fact slow the rise of oxygenation (and thus stymie complex life rather

than promote it).

[115]

Computer modelling by Tilman Spohn in 2014 found that plate tectonics

on Earth may have arisen from the effects of complex life's emergence,

rather than the other way around as the Rare Earth might suggest. The

action of lichens on rock may have contributed to the formation of

subduction zones in the presence of water.

[116]

Kasting argues that if oxygenation caused the Cambrian explosion then

any planet with oxygen producing photosynthesis should have complex

life.

[117]

A magnetic field may not be a requirement

The

importance of Earth's magnetic field to the development of complex life

has been disputed. Kasting argues that the atmosphere provides

sufficient protection against cosmic rays even during times of magnetic

pole reversal and atmosphere loss by sputtering.

[78] Kasting also dismisses the role of the magnetic field in the evolution of eukaryotes, citing the age of the oldest known

magnetofossils.

[118]

A large moon may neither be rare nor necessary

The requirement of a large moon (Rare Earth equation factor

)

has also been challenged. Even if it were required, such an occurrence

may not be as unique as predicted by the Rare Earth Hypothesis. Recent

work by

Edward Belbruno and

J. Richard Gott of Princeton University suggests that giant impacts such as those that may have formed the

Moon can indeed form in planetary

trojan points (

L4 or

L5 Lagrangian point) which means that similar circumstances may occur in other planetary systems.

[119]

Collision between two planetary bodies (artist concept).

Rare Earth's assertion that the Moon's stabilization of Earth's

obliquity and spin is a requirement for complex life has been

questioned. Kasting argues that a moonless Earth would still possess

habitats with climates suitable for complex life and questions whether

the spin rate of a moonless Earth can be predicted.

[78] Although the

giant impact theory

posits that the impact forming the Moon increased Earth's rotational

speed to make a day about 5 hours long, the Moon has slowly "

stolen"

much of this speed to reduce Earth's solar day since then to about 24

hours and continues to do so: in 100 million years Earth's solar day

will be roughly 24 hours 38 minutes (the same as Mars's solar day); in 1

billion years, 30 hours 23 minutes. Larger secondary bodies would exert

proportionally larger tidal forces that would in turn decelerate their

primaries faster and potentially increase the solar day of a planet in

all other respects like earth to over 120 hours within a few billion

years. This long solar day would make effective heat dissipation for

organisms in the tropics and subtropics extremely difficult in a similar

manner to tidal locking to a red dwarf star. Short days (high rotation

speed) causes high wind speeds at ground level. Long days (slow rotation

speed) cause the day and night temperatures to be too extreme.

[120]

Many Rare Earth proponents argue that the Earth's plate tectonics

would probably not exist if not for the tidal forces of the Moon.

[121][122]

The hypothesis that the Moon's tidal influence initiated or sustained

Earth's plate tectonics remains unproven, though at least one study

implies a temporal correlation to the formation of the Moon.

[123] Evidence for the past existence of plate tectonics on planets like Mars

[124]

which may never have had a large moon would counter this argument.

Kasting argues that a large moon is not required to initiate plate

tectonics.

[78]

Complex life may arise in alternative habitats

Complex life may exist in environments similar to

black smokers on Earth.

Rare Earth proponents argue that simple life may be common, though

complex life requires specific environmental conditions to arise.

Critics consider life could arise on a

moon

of a gas giant, though this is less likely if life requires

volcanicity. The moon must have stresses to induce tidal heating, but

not so dramatic as seen on Jupiter's Io. However, the moon is within the

gas giant's intense radiation belts, sterilizing any biodiversity

before it can get established.

Dirk Schulze-Makuch disputes this, hypothesizing alternative biochemistries for alien life.

[125]

While Rare Earth proponents argue that only microbial extremophiles

could exist in subsurface habitats beyond Earth, some argue that complex

life can also arise in these environments. Examples of extremophile

animals such as the

Hesiocaeca methanicola, an animal that inhabits ocean floor

methane clathrates substances more commonly found in the outer Solar System, the

tardigrades which can survive in the vacuum of space

[126] or

Halicephalobus mephisto

which exists in crushing pressure, scorching temperatures and extremely

low oxygen levels 3.6 kilometres deep in the Earth's crust,

[127] are sometimes cited by critics as complex life capable of thriving in "alien" environments.

Jill Tarter

counters the classic counterargument that these species adapted to

these environments rather than arose in them, by suggesting that we

cannot assume conditions for life to emerge which are not actually

known.

[128] There are suggestions that complex life could arise in sub-surface

conditions which may be similar to those where life may have arisen on

Earth, such as the

tidally heated subsurfaces of Europa or Enceladus.

[129][130] Ancient circumvental ecosystems such as these support complex life on Earth such as

Riftia pachyptila that exist completely independent of the surface biosphere.

[131]

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{NO2}->[h \nu] {NO}+ {O}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/34fed23155c119954fa08461965c09c3d04f2921)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{NO2}+ {O2}->[h \nu] {NO}+ {O3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e1d3ed7bb48f69dfa453b9727ecbe7863804988)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{CFCS}->[h \nu] {Cl.}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/088ca5853b063101511fb5a21520e648c6d87466)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{O3}->[h \nu] {O}+ {O2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f2db8df4adfc00e58fc18167823562cdbaa169d8)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{2O3}->[h \nu] 3O2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/29b154561607496cd0feb37e02045d192ecbb4e8)