Neurolinguistics is the study of the neural mechanisms in the human brain that control the comprehension, production, and acquisition of language. As an interdisciplinary field, neurolinguistics draws methods and theories from fields such as neuroscience, linguistics, cognitive science, communication disorders and neuropsychology. Researchers are drawn to the field from a variety of backgrounds, bringing along a variety of experimental techniques as well as widely varying theoretical perspectives. Much work in neurolinguistics is informed by models in psycholinguistics and theoretical linguistics, and is focused on investigating how the brain can implement the processes that theoretical and psycholinguistics propose are necessary in producing and comprehending language. Neurolinguists study the physiological mechanisms by which the brain processes information related to language, and evaluate linguistic and psycholinguistic theories, using aphasiology, brain imaging, electrophysiology, and computer modeling.

History

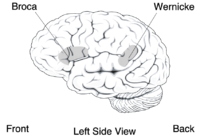

Neurolinguistics is historically rooted in the development in the 19th century of aphasiology, the study of linguistic deficits (aphasias) occurring as the result of brain damage. Aphasiology attempts to correlate structure to function by analyzing the effect of brain injuries on language processing. One of the first people to draw a connection between a particular brain area and language processing was Paul Broca, a French surgeon who conducted autopsies on numerous individuals who had speaking deficiencies, and found that most of them had brain damage (or lesions) on the left frontal lobe, in an area now known as Broca's area. Phrenologists had made the claim in the early 19th century that different brain regions carried out different functions and that language was mostly controlled by the frontal regions of the brain, but Broca's research was possibly the first to offer empirical evidence for such a relationship, and has been described as "epoch-making" and "pivotal" to the fields of neurolinguistics and cognitive science. Later, Carl Wernicke, after whom Wernicke's area is named, proposed that different areas of the brain were specialized for different linguistic tasks, with Broca's area handling the motor production of speech, and Wernicke's area handling auditory speech comprehension.

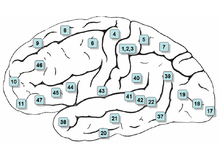

The work of Broca and Wernicke established the field of aphasiology and the idea that language can be studied through examining physical characteristics of the brain. Early work in aphasiology also benefited from the early twentieth-century work of Korbinian Brodmann, who "mapped" the surface of the brain, dividing it up into numbered areas based on each area's cytoarchitecture (cell structure) and function; these areas, known as Brodmann areas, are still widely used in neuroscience today.

The coining of the term "neurolinguistics" is attributed to Edith Crowell Trager, Henri Hecaen and Alexandr Luria, in the late 1940s and 1950s; Luria's book "Problems in Neurolinguistics" is likely the first book with Neurolinguistics in the title. Harry Whitaker popularized neurolinguistics in the United States in the 1970s, founding the journal "Brain and Language" in 1974.

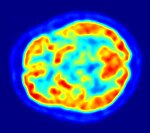

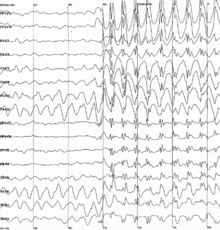

Although aphasiology is the historical core of neurolinguistics, in recent years the field has broadened considerably, thanks in part to the emergence of new brain imaging technologies (such as PET and fMRI) and time-sensitive electrophysiological techniques (EEG and MEG), which can highlight patterns of brain activation as people engage in various language tasks; electrophysiological techniques, in particular, emerged as a viable method for the study of language in 1980 with the discovery of the N400, a brain response shown to be sensitive to semantic issues in language comprehension. The N400 was the first language-relevant event-related potential to be identified, and since its discovery EEG and MEG have become increasingly widely used for conducting language research.

Interaction with other fields

Neurolinguistics is closely related to the field of psycholinguistics, which seeks to elucidate the cognitive mechanisms of language by employing the traditional techniques of experimental psychology; today, psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic theories often inform one another, and there is much collaboration between the two fields.

Much work in neurolinguistics involves testing and evaluating theories put forth by psycholinguists and theoretical linguists. In general, theoretical linguists propose models to explain the structure of language and how language information is organized, psycholinguists propose models and algorithms to explain how language information is processed in the mind, and neurolinguists analyze brain activity to infer how biological structures (populations and networks of neurons) carry out those psycholinguistic processing algorithms. For example, experiments in sentence processing have used the ELAN, N400, and P600 brain responses to examine how physiological brain responses reflect the different predictions of sentence processing models put forth by psycholinguists, such as Janet Fodor and Lyn Frazier's "serial" model, and Theo Vosse and Gerard Kempen's "unification model". Neurolinguists can also make new predictions about the structure and organization of language based on insights about the physiology of the brain, by "generalizing from the knowledge of neurological structures to language structure".

Neurolinguistics research is carried out in all the major areas of linguistics; the main linguistic subfields, and how neurolinguistics addresses them, are given in the table below.

| Subfield | Description | Research questions in neurolinguistics |

|---|---|---|

| Phonetics | the study of speech sounds | how the brain extracts speech sounds from an acoustic signal, how the brain separates speech sounds from background noise |

| Phonology | the study of how sounds are organized in a language | how the phonological system of a particular language is represented in the brain |

| Morphology and lexicology | the study of how words are structured and stored in the mental lexicon | how the brain stores and accesses words that a person knows |

| Syntax | the study of how multiple-word utterances are constructed | how the brain combines words into constituents and sentences; how structural and semantic information is used in understanding sentences |

| Semantics | the study of how meaning is encoded in language |

Topics considered

Neurolinguistics research investigates several topics, including where language information is processed, how language processing unfolds over time, how brain structures are related to language acquisition and learning, and how neurophysiology can contribute to speech and language pathology.

Localizations of language processes

Much work in neurolinguistics has, like Broca's and Wernicke's early studies, investigated the locations of specific language "modules" within the brain. Research questions include what course language information follows through the brain as it is processed, whether or not particular areas specialize in processing particular sorts of information, how different brain regions interact with one another in language processing, and how the locations of brain activation differ when a subject is producing or perceiving a language other than his or her first language.

Time course of language processes

Another area of neurolinguistics literature involves the use of electrophysiological techniques to analyze the rapid processing of language in time. The temporal ordering of specific patterns of brain activity may reflect discrete computational processes that the brain undergoes during language processing; for example, one neurolinguistic theory of sentence parsing proposes that three brain responses (the ELAN, N400, and P600) are products of three different steps in syntactic and semantic processing.

Language acquisition

Another topic is the relationship between brain structures and language acquisition. Research in first language acquisition has already established that infants from all linguistic environments go through similar and predictable stages (such as babbling), and some neurolinguistics research attempts to find correlations between stages of language development and stages of brain development, while other research investigates the physical changes (known as neuroplasticity) that the brain undergoes during second language acquisition, when adults learn a new language. Neuroplasticity is observed when both Second Language acquisition and Language Learning experience are induced, the result of this language exposure concludes that an increase of gray and white matter could be found in children, young adults and the elderly.

Ping Li, Jennifer Legault, Kaitlyn A. Litcofsky, May 2014. Neuroplasticity as a function of second language learning: Anatomical changes in the human brain Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System & Behavior, 410.1016/j.cortex.2014.05.00124996640

Language pathology

Neurolinguistic techniques are also used to study disorders and breakdowns in language, such as aphasia and dyslexia, and how they relate to physical characteristics of the brain.

Technology used

Since one of the focuses of this field is the testing of linguistic and psycholinguistic models, the technology used for experiments is highly relevant to the study of neurolinguistics. Modern brain imaging techniques have contributed greatly to a growing understanding of the anatomical organization of linguistic functions. Brain imaging methods used in neurolinguistics may be classified into hemodynamic methods, electrophysiological methods, and methods that stimulate the cortex directly.

Hemodynamic

Hemodynamic techniques take advantage of the fact that when an area of the brain works at a task, blood is sent to supply that area with oxygen (in what is known as the Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent, or BOLD, response). Such techniques include PET and fMRI. These techniques provide high spatial resolution, allowing researchers to pinpoint the location of activity within the brain; temporal resolution (or information about the timing of brain activity), on the other hand, is poor, since the BOLD response happens much more slowly than language processing. In addition to demonstrating which parts of the brain may subserve specific language tasks or computations, hemodynamic methods have also been used to demonstrate how the structure of the brain's language architecture and the distribution of language-related activation may change over time, as a function of linguistic exposure.

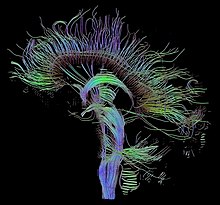

In addition to PET and fMRI, which show which areas of the brain are activated by certain tasks, researchers also use diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which shows the neural pathways that connect different brain areas, thus providing insight into how different areas interact. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is another hemodynamic method used in language tasks.

Electrophysiological

Electrophysiological techniques take advantage of the fact that when a group of neurons in the brain fire together, they create an electric dipole or current. The technique of EEG measures this electric current using sensors on the scalp, while MEG measures the magnetic fields that are generated by these currents. In addition to these non-invasive methods, electrocorticography has also been used to study language processing. These techniques are able to measure brain activity from one millisecond to the next, providing excellent temporal resolution, which is important in studying processes that take place as quickly as language comprehension and production. On the other hand, the location of brain activity can be difficult to identify in EEG; consequently, this technique is used primarily to how language processes are carried out, rather than where. Research using EEG and MEG generally focuses on event-related potentials (ERPs), which are distinct brain responses (generally realized as negative or positive peaks on a graph of neural activity) elicited in response to a particular stimulus. Studies using ERP may focus on each ERP's latency (how long after the stimulus the ERP begins or peaks), amplitude (how high or low the peak is), or topography (where on the scalp the ERP response is picked up by sensors). Some important and common ERP components include the N400 (a negativity occurring at a latency of about 400 milliseconds), the mismatch negativity, the early left anterior negativity (a negativity occurring at an early latency and a front-left topography), the P600, and the lateralized readiness potential.

Experimental design

Experimental techniques

Neurolinguists employ a variety of experimental techniques in order to use brain imaging to draw conclusions about how language is represented and processed in the brain. These techniques include the subtraction paradigm, mismatch design, violation-based studies, various forms of priming, and direct stimulation of the brain.

Subtraction

Many language studies, particularly in fMRI, use the subtraction paradigm, in which brain activation in a task thought to involve some aspect of language processing is compared against activation in a baseline task thought to involve similar non-linguistic processes but not to involve the linguistic process. For example, activations while participants read words may be compared to baseline activations while participants read strings of random letters (in attempt to isolate activation related to lexical processing—the processing of real words), or activations while participants read syntactically complex sentences may be compared to baseline activations while participants read simpler sentences.

Mismatch paradigm

The mismatch negativity (MMN) is a rigorously documented ERP component frequently used in neurolinguistic experiments. It is an electrophysiological response that occurs in the brain when a subject hears a "deviant" stimulus in a set of perceptually identical "standards" (as in the sequence s s s s s s s d d s s s s s s d s s s s s d). Since the MMN is elicited only in response to a rare "oddball" stimulus in a set of other stimuli that are perceived to be the same, it has been used to test how speakers perceive sounds and organize stimuli categorically. For example, a landmark study by Colin Phillips and colleagues used the mismatch negativity as evidence that subjects, when presented with a series of speech sounds with acoustic parameters, perceived all the sounds as either /t/ or /d/ in spite of the acoustic variability, suggesting that the human brain has representations of abstract phonemes—in other words, the subjects were "hearing" not the specific acoustic features, but only the abstract phonemes. In addition, the mismatch negativity has been used to study syntactic processing and the recognition of word category.

Violation-based

Many studies in neurolinguistics take advantage of anomalies or violations of syntactic or semantic rules in experimental stimuli, and analyzing the brain responses elicited when a subject encounters these violations. For example, sentences beginning with phrases such as *the garden was on the worked, which violates an English phrase structure rule, often elicit a brain response called the early left anterior negativity (ELAN). Violation techniques have been in use since at least 1980, when Kutas and Hillyard first reported ERP evidence that semantic violations elicited an N400 effect. Using similar methods, in 1992, Lee Osterhout first reported the P600 response to syntactic anomalies. Violation designs have also been used for hemodynamic studies (fMRI and PET): Embick and colleagues, for example, used grammatical and spelling violations to investigate the location of syntactic processing in the brain using fMRI. Another common use of violation designs is to combine two kinds of violations in the same sentence and thus make predictions about how different language processes interact with one another; this type of crossing-violation study has been used extensively to investigate how syntactic and semantic processes interact while people read or hear sentences.

Priming

In psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics, priming refers to the phenomenon whereby a subject can recognize a word more quickly if he or she has recently been presented with a word that is similar in meaning or morphological makeup (i.e., composed of similar parts). If a subject is presented with a "prime" word such as doctor and then a "target" word such as nurse, if the subject has a faster-than-usual response time to nurse then the experimenter may assume that word nurse in the brain had already been accessed when the word doctor was accessed. Priming is used to investigate a wide variety of questions about how words are stored and retrieved in the brain and how structurally complex sentences are processed.

Stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a new noninvasive technique for studying brain activity, uses powerful magnetic fields that are applied to the brain from outside the head. It is a method of exciting or interrupting brain activity in a specific and controlled location, and thus is able to imitate aphasic symptoms while giving the researcher more control over exactly which parts of the brain will be examined. As such, it is a less invasive alternative to direct cortical stimulation, which can be used for similar types of research but requires that the subject's scalp be removed, and is thus only used on individuals who are already undergoing a major brain operation (such as individuals undergoing surgery for epilepsy). The logic behind TMS and direct cortical stimulation is similar to the logic behind aphasiology: if a particular language function is impaired when a specific region of the brain is knocked out, then that region must be somehow implicated in that language function. Few neurolinguistic studies to date have used TMS; direct cortical stimulation and cortical recording (recording brain activity using electrodes placed directly on the brain) have been used with macaque monkeys to make predictions about the behavior of human brains.

Subject tasks

In many neurolinguistics experiments, subjects do not simply sit and listen to or watch stimuli, but also are instructed to perform some sort of task in response to the stimuli. Subjects perform these tasks while recordings (electrophysiological or hemodynamic) are being taken, usually in order to ensure that they are paying attention to the stimuli. At least one study has suggested that the task the subject does has an effect on the brain responses and the results of the experiment.

Lexical decision

The lexical decision task involves subjects seeing or hearing an isolated word and answering whether or not it is a real word. It is frequently used in priming studies, since subjects are known to make a lexical decision more quickly if a word has been primed by a related word (as in "doctor" priming "nurse").

Grammaticality judgment, acceptability judgment

Many studies, especially violation-based studies, have subjects make a decision about the "acceptability" (usually grammatical acceptability or semantic acceptability) of stimuli. Such a task is often used to "ensure that subjects [are] reading the sentences attentively and that they [distinguish] acceptable from unacceptable sentences in the way the [experimenter] expect[s] them to do."

Experimental evidence has shown that the instructions given to subjects in an acceptability judgment task can influence the subjects' brain responses to stimuli. One experiment showed that when subjects were instructed to judge the "acceptability" of sentences they did not show an N400 brain response (a response commonly associated with semantic processing), but that they did show that response when instructed to ignore grammatical acceptability and only judge whether or not the sentences "made sense".

Probe verification

Some studies use a "probe verification" task rather than an overt acceptability judgment; in this paradigm, each experimental sentence is followed by a "probe word", and subjects must answer whether or not the probe word had appeared in the sentence. This task, like the acceptability judgment task, ensures that subjects are reading or listening attentively, but may avoid some of the additional processing demands of acceptability judgments, and may be used no matter what type of violation is being presented in the study.

Truth-value judgment

Subjects may be instructed not to judge whether or not the sentence is grammatically acceptable or logical, but whether the proposition expressed by the sentence is true or false. This task is commonly used in psycholinguistic studies of child language.

Active distraction and double-task

Some experiments give subjects a "distractor" task to ensure that subjects are not consciously paying attention to the experimental stimuli; this may be done to test whether a certain computation in the brain is carried out automatically, regardless of whether the subject devotes attentional resources to it. For example, one study had subjects listen to non-linguistic tones (long beeps and buzzes) in one ear and speech in the other ear, and instructed subjects to press a button when they perceived a change in the tone; this supposedly caused subjects not to pay explicit attention to grammatical violations in the speech stimuli. The subjects showed a mismatch response (MMN) anyway, suggesting that the processing of the grammatical errors was happening automatically, regardless of attention—or at least that subjects were unable to consciously separate their attention from the speech stimuli.

Another related form of experiment is the double-task experiment, in which a subject must perform an extra task (such as sequential finger-tapping or articulating nonsense syllables) while responding to linguistic stimuli; this kind of experiment has been used to investigate the use of working memory in language processing.