Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe

3O

4, 72.4% Fe), hematite (Fe

2O

3, 69.9% Fe), goethite (FeO(OH), 62.9% Fe), limonite (FeO(OH)·n(H2O), 55% Fe) or siderite (FeCO3, 48.2% Fe).

Ores containing very high quantities of hematite or magnetite, typically greater than about 60% iron, are known as natural ore or direct shipping ore, and can be fed directly into iron-making blast furnaces. Iron ore is the raw material used to make pig iron, which is one of the main raw materials to make steel—98% of the mined iron ore is used to make steel. In 2011 the Financial Times quoted Christopher LaFemina, mining analyst at Barclays Capital, saying that iron ore is "more integral to the global economy than any other commodity, except perhaps oil".

Sources

Metallic iron is virtually unknown on the surface of the Earth except as iron-nickel alloys from meteorites and very rare forms of deep mantle xenoliths. Some iron meteorites are thought to have originated from accreted bodies 1,000 km in diameter or larger The origin of iron can be ultimately traced to the formation through nuclear fusion in stars, and most of the iron is thought to have originated in dying stars that are large enough to collapse or explode as supernovae. Although iron is the fourth-most abundant element in the Earth's crust, composing about 5%, the vast majority is bound in silicate or, more rarely, carbonate minerals (for more information, see iron cycle). The thermodynamic barriers to separating pure iron from these minerals are formidable and energy-intensive; therefore, all sources of iron used by human industry exploit comparatively rarer iron oxide minerals, primarily hematite.

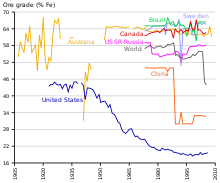

Prior to the industrial revolution, most iron was obtained from widely available goethite or bog ore, for example, during the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Prehistoric societies used laterite as a source of iron ore. Historically, much of the iron ore utilized by industrialized societies has been mined from predominantly hematite deposits with grades of around 70% Fe. These deposits are commonly referred to as "direct shipping ores" or "natural ores". Increasing iron ore demand, coupled with the depletion of high-grade hematite ores in the United States, led after World War II to the development of lower-grade iron ore sources, principally the utilization of magnetite and taconite.

Iron ore mining methods vary by the type of ore being mined. There are four main types of iron ore deposits worked currently, depending on the mineralogy and geology of the ore deposits. These are magnetite, titanomagnetite, massive hematite and pisolitic ironstone deposits.

Banded iron formations

Banded iron formations (BIFs) are sedimentary rocks containing more than 15% iron composed predominantly of thinly bedded iron minerals and silica (as quartz). Banded iron formations occur exclusively in Precambrian rocks, and are commonly weakly to intensely metamorphosed. Banded iron formations may contain iron in carbonates (siderite or ankerite) or silicates (minnesotaite, greenalite, or grunerite), but in those mined as iron ores, oxides (magnetite or hematite) are the principal iron mineral. Banded iron formations are known as taconite within North America.

The mining involves moving tremendous amounts of ore and waste. The waste comes in two forms: non-ore bedrock in the mine (overburden or interburden locally known as mullock), and unwanted minerals, which are an intrinsic part of the ore rock itself (gangue). The mullock is mined and piled in waste dumps, and the gangue is separated during the beneficiation process and is removed as tailings. Taconite tailings are mostly the mineral quartz, which is chemically inert. This material is stored in large, regulated water settling ponds.

Magnetite ores

The key parameters for magnetite ore being economic are the crystallinity of the magnetite, the grade of the iron within the banded iron formation host rock, and the contaminant elements which exist within the magnetite concentrate. The size and strip ratio of most magnetite resources is irrelevant as a banded iron formation can be hundreds of meters thick, extend hundreds of kilometers along strike, and can easily come to more than three billion or more tonnes of contained ore.

The typical grade of iron at which a magnetite-bearing banded iron formation becomes economic is roughly 25% iron, which can generally yield a 33% to 40% recovery of magnetite by weight, to produce a concentrate grading in excess of 64% iron by weight. The typical magnetite iron ore concentrate has less than 0.1% phosphorus, 3–7% silica and less than 3% aluminium.

Currently magnetite iron ore is mined in Minnesota and Michigan in the U.S., Eastern Canada and Northern Sweden. Magnetite-bearing banded iron formation is currently mined extensively in Brazil, which exports significant quantities to Asia, and there is a nascent and large magnetite iron ore industry in Australia.

Direct-shipping (hematite) ores

Direct-shipping iron ore (DSO) deposits (typically composed of hematite) are currently exploited on all continents except Antarctica, with the largest intensity in South America, Australia and Asia. Most large hematite iron ore deposits are sourced from altered banded iron formations and rarely igneous accumulations.

DSO deposits are typically rarer than the magnetite-bearing BIF or other rocks which form its main source or protolith rock, but are considerably cheaper to mine and process as they require less beneficiation due to the higher iron content. However, DSO ores can contain significantly higher concentrations of penalty elements, typically being higher in phosphorus, water content (especially pisolite sedimentary accumulations) and aluminium (clays within pisolites). Export-grade DSO ores are generally in the 62–64% Fe range.

Magmatic magnetite ore deposits

Granite and ultrapotassic igneous rocks were sometimes used to segregate magnetite crystals and form masses of magnetite suitable for economic concentration. A few iron ore deposits, notably in Chile, are formed from volcanic flows containing significant accumulations of magnetite phenocrysts. Chilean magnetite iron ore deposits within the Atacama Desert have also formed alluvial accumulations of magnetite in streams leading from these volcanic formations.

Some magnetite skarn and hydrothermal deposits have been worked in the past as high-grade iron ore deposits requiring little beneficiation. There are several granite-associated deposits of this nature in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Other sources of magnetite iron ore include metamorphic accumulations of massive magnetite ore such as at Savage River, Tasmania, formed by shearing of ophiolite ultramafics.

Another, minor, source of iron ores are magmatic accumulations in layered intrusions which contain a typically titanium-bearing magnetite often with vanadium.

These ores form a niche market, with specialty smelters used to recover

the iron, titanium and vanadium. These ores are beneficiated

essentially similar to banded iron formation ores, but usually are more

easily upgraded via crushing and screening. The typical titanomagnetite concentrate grades 57% Fe, 12% Ti and 0.5% V

2O

5.

Mine tailings

For every one ton of iron ore concentrate produced approximately 2.5–3.0 tons of iron ore tailings will be discharged. Statistics show that there are 130 million tons of iron ore discharged every year. If, for example, the mine tailings contain an average of approximately 11% iron there would be approximately 1.41 million tons of iron wasted annually. These tailings are also high in other useful metals such as copper, nickel, and cobalt, and they can be used for road-building materials like pavement and filler and building materials such as cement, low-grade glass, and wall materials. While tailings are a relatively low-grade ore, they are also inexpensive to collect as they do not have to be mined. Because of this companies such as Magnetation have started reclamation projects where they use iron ore tailings as a source of metallic iron.

The two main methods of recycling iron from iron ore tailings are magnetizing roasting and direct reduction. Magnetizing roasting uses temperatures between 700 and 900 °C for a time of under 1 hour to produce an iron concentrate (Fe3O4) to be used for iron smelting. For magnetizing roasting it is important to have a reducing atmosphere to prevent oxidization and the formation of Fe2O3 because it is harder to separate as it is less magnetic. Direct reduction uses hotter temperatures of over 1000 °C and longer times of 2–5 hours. Direct reduction is used to produce sponge iron (Fe) to be used for steel making. Direct reduction requires more energy as the temperatures are higher and the time is longer and it requires more reducing agent than magnetizing roasting.

Extraction

Lower-grade sources of iron ore generally require beneficiation, using techniques like crushing, milling, gravity or heavy media separation, screening, and silica froth flotation to improve the concentration of the ore and remove impurities. The results, high-quality fine ore powders, are known as fines.

Magnetite

Magnetite is magnetic, and hence easily separated from the gangue minerals and capable of producing a high-grade concentrate with very low levels of impurities.

The grain size of the magnetite and its degree of commingling with the silica groundmass determine the grind size to which the rock must be comminuted to enable efficient magnetic separation to provide a high purity magnetite concentrate. This determines the energy inputs required to run a milling operation.

Mining of banded iron formations involves coarse crushing and screening, followed by rough crushing and fine grinding to comminute the ore to the point where the crystallized magnetite and quartz are fine enough that the quartz is left behind when the resultant powder is passed under a magnetic separator.

Generally most magnetite banded iron formation deposits must be ground to between 32 and 45 micrometers in order to produce a low-silica magnetite concentrate. Magnetite concentrate grades are generally in excess of 70% iron by weight and usually are low phosphorus, low aluminium, low titanium and low silica and demand a premium price.

Hematite

Due to the high density of hematite relative to associated silicate gangue, hematite beneficiation usually involves a combination of beneficiation techniques.

One method relies on passing the finely crushed ore over a slurry containing magnetite or other agent such as ferrosilicon which increases its density. When the density of the slurry is properly calibrated, the hematite will sink and the silicate mineral fragments will float and can be removed.

Production and consumption

| Country | Production |

|---|---|

| Australia | 817 |

| Brazil | 397 |

| China | 375* |

| India | 156 |

| Russia | 101 |

| South Africa | 73 |

| Ukraine | 67 |

| United States | 46 |

| Canada | 46 |

| Iran | 27 |

| Sweden | 25 |

| Kazakhstan | 21 |

| Other countries | 132 |

| Total world | 2,280 |

Iron is the world's most commonly used metal—steel, of which iron ore is the key ingredient, representing almost 95% of all metal used per year. It is used primarily in structures, ships, automobiles, and machinery.

Iron-rich rocks are common worldwide, but ore-grade commercial mining operations are dominated by the countries listed in the table aside. The major constraint to economics for iron ore deposits is not necessarily the grade or size of the deposits, because it is not particularly hard to geologically prove enough tonnage of the rocks exist. The main constraint is the position of the iron ore relative to market, the cost of rail infrastructure to get it to market and the energy cost required to do so.

Mining iron ore is a high-volume, low-margin business, as the value of iron is significantly lower than base metals. It is highly capital intensive, and requires significant investment in infrastructure such as rail in order to transport the ore from the mine to a freight ship. For these reasons, iron ore production is concentrated in the hands of a few major players.

World production averages two billion metric tons of raw ore annually. The world's largest producer of iron ore is the Brazilian mining corporation Vale, followed by Australian companies Rio Tinto Group and BHP. A further Australian supplier, Fortescue Metals Group Ltd, has helped bring Australia's production to first in the world.

The seaborne trade in iron ore—that is, iron ore to be shipped to other countries—was 849 million tonnes in 2004. Australia and Brazil dominate the seaborne trade, with 72% of the market. BHP, Rio and Vale control 66% of this market between them.

In Australia, iron ore is won from three main sources: pisolite "channel iron deposit" ore derived by mechanical erosion of primary banded-iron formations and accumulated in alluvial channels such as at Pannawonica, Western Australia; and the dominant metasomatically-altered banded iron formation-related ores such as at Newman, the Chichester Range, the Hamersley Range and Koolyanobbing, Western Australia. Other types of ore are coming to the fore recently, such as oxidised ferruginous hardcaps, for instance laterite iron ore deposits near Lake Argyle in Western Australia.

The total recoverable reserves of iron ore in India are about 9,602 million tonnes of hematite and 3,408 million tonnes of magnetite. Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Odisha, Goa, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu are the principal Indian producers of iron ore. World consumption of iron ore grows 10% per annum on average with the main consumers being China, Japan, Korea, the United States and the European Union.

China is currently the largest consumer of iron ore, which translates to be the world's largest steel producing country. It is also the largest importer, buying 52% of the seaborne trade in iron ore in 2004. China is followed by Japan and Korea, which consume a significant amount of raw iron ore and metallurgical coal. In 2006, China produced 588 million tons of iron ore, with an annual growth of 38%.

Iron ore market

25th October 2010 - 4th August 2022

Over the last 40 years, iron ore prices have been decided in closed-door negotiations between the small handful of miners and steelmakers which dominate both spot and contract markets. Traditionally, the first deal reached between these two groups sets a benchmark to be followed by the rest of the industry.

In recent years, however, this benchmark system has begun to break down, with participants along both demand and supply chains calling for a shift to short term pricing. Given that most other commodities already have a mature market-based pricing system, it is natural for iron ore to follow suit. To answer increasing market demands for more transparent pricing, a number of financial exchanges and/or clearing houses around the world have offered iron ore swaps clearing. The CME group, SGX (Singapore Exchange), London Clearing House (LCH.Clearnet), NOS Group and ICEX (Indian Commodities Exchange) all offer cleared swaps based on The Steel Index's (TSI) iron ore transaction data. The CME also offers a Platts-based swap, in addition to their TSI swap clearing. The ICE (Intercontinental Exchange) offers a Platts-based swap clearing service also. The swaps market has grown quickly, with liquidity clustering around TSI's pricing. By April 2011, over US$5.5 billion worth of iron ore swaps have been cleared basis TSI prices. By August 2012, in excess of one million tonnes of swaps trading per day was taking place regularly, basis TSI.

A relatively new development has also been the introduction of iron ore options, in addition to swaps. The CME group has been the venue most utilised for clearing of options written against TSI, with open interest at over 12,000 lots in August 2012.

Singapore Mercantile Exchange (SMX) has launched the world first global iron ore futures contract, based on the Metal Bulletin Iron Ore Index (MBIOI) which utilizes daily price data from a broad spectrum of industry participants and independent Chinese steel consultancy and data provider Shanghai Steelhome's widespread contact base of steel producers and iron ore traders across China. The futures contract has seen monthly volumes over 1.5 million tonnes after eight months of trading.

This move follows a switch to index-based quarterly pricing by the world's three largest iron ore miners—Vale, Rio Tinto and BHP—in early 2010, breaking a 40-year tradition of benchmark annual pricing.

Abundance by country

Available world iron ore resources

Iron is the most abundant element on earth but not in the crust. The extent of the accessible iron ore reserves is not known, though Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute suggested in 2006 that iron ore could run out within 64 years (that is, by 2070), based on 2% growth in demand per year.

Australia

Geoscience Australia calculates that the country's "economic demonstrated resources" of iron currently amount to 24 gigatonnes, or 24 billion tonnes. Another estimate places Australia's reserves of iron ore at 52 billion tonnes, or 30 per cent of the world’s estimated 170 billion tonnes, of which Western Australia accounts for 28 billion tonnes. The current production rate from the Pilbara region of Western Australia is approximately 430 million tonnes a year and rising. Gavin Mudd (RMIT University) and Jonathon Law (CSIRO) expect it to be gone within 30–50 years and 56 years, respectively. These 2010 estimates require on-going review to take into account shifting demand for lower-grade iron ore and improving mining and recovery techniques (allowing deeper mining below the groundwater table).

United States

In 2014, mines in the United States produced 57.5 million metric tons of iron ore with an estimated value of $5.1 billion. Iron mining in the United States is estimated to have accounted for 2% of the world's iron ore output. In the United States there are twelve iron ore mines with nine being open pit mines and three being reclamation operations. There were also ten pelletizing plants, nine concentration plants, two direct-reduced iron (DRI) plants and one iron nugget plant that were operating in 2014. In the United States the majority of iron ore mining is in the iron ranges around Lake Superior. These iron ranges occur in Minnesota and Michigan which combined accounted for 93% of the usable iron ore produced in the United States in 2014. Seven of the nine operational open pit mines in the United States are located in Minnesota as well as two of the three tailings reclamation operations. The other two active open pit mines were located in Michigan, in 2016 one of the two mines shut down. There have also been iron ore mines in Utah and Alabama; however, the last iron ore mine in Utah shut down in 2014 and the last iron ore mine in Alabama shut down in 1975.

Canada

In 2017, Canadian iron ore mines produced 49 million tons of iron ore in concentrate pellets and 13.6 million tons of crude steel. Of the 13.6 million tons of steel 7 million was exported, and 43.1 million tons of iron ore was exported at a value of $4.6 billion. Of the iron ore exported 38.5% of the volume was iron ore pellets with a value of $2.3 billion and 61.5% was iron ore concentrates with a value of $2.3 billion. Forty-six per cent of Canada's iron ore comes from the Iron Ore Company of Canada mine, in Labrador City, Newfoundland, with secondary sources including, the Mary River Mine, Nunavut.

Brazil

Brazil is the second-largest producer of iron ore with Australia being the largest. In 2015 Brazil exported 397 million tons of usable iron ore. In December 2017 Brazil exported 346,497 metric tons of iron ore and from December 2007 to May 2018 they exported a monthly average of 139,299 metric tons.

Ukraine

According to the U.S. Geological Survey's 2021 Report on iron ore, Ukraine is estimated to have produced 62 million tons of iron ore in 2020 (2019: 63 million tons), placing it as the seventh largest global centre of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa. Producers of iron ore in Ukraine include: Ferrexpo, Metinvest and ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih.

India

According to the U.S. Geological Survey's 2021 Report on iron ore, India is estimated to produce 59 million tons of iron ore in 2020 (2019: 52 million tons), placing it as the seventh largest global centre of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, Russia and South Africa and Ukraine.

Smelting

Iron ores consist of oxygen and iron atoms bonded together into molecules. To convert it to metallic iron it must be smelted or sent through a direct reduction process to remove the oxygen. Oxygen-iron bonds are strong, and to remove the iron from the oxygen, a stronger elemental bond must be presented to attach to the oxygen. Carbon is used because the strength of a carbon-oxygen bond is greater than that of the iron-oxygen bond, at high temperatures. Thus, the iron ore must be powdered and mixed with coke, to be burnt in the smelting process.

Carbon monoxide

is the primary ingredient of chemically stripping oxygen from iron.

Thus, the iron and carbon smelting must be kept at an oxygen-deficient

(reducing) state to promote burning of carbon to produce CO not CO

2.

- Air blast and charcoal (coke): 2 C + O2 → 2 CO

- Carbon monoxide (CO) is the principal reduction agent.

- Stage One: 3 Fe2O3 + CO → 2 Fe3O4 + CO2

- Stage Two: Fe3O4 + CO → 3 FeO + CO2

- Stage Three: FeO + CO → Fe + CO2

- Limestone calcining: CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

- Lime acting as flux: CaO + SiO2 → CaSiO3

Trace elements

The inclusion of even small amounts of some elements can have profound effects on the behavioral characteristics of a batch of iron or the operation of a smelter. These effects can be both good and bad, some catastrophically bad. Some chemicals are deliberately added such as flux which makes a blast furnace more efficient. Others are added because they make the iron more fluid, harder, or give it some other desirable quality. The choice of ore, fuel, and flux determine how the slag behaves and the operational characteristics of the iron produced. Ideally iron ore contains only iron and oxygen. In reality this is rarely the case. Typically, iron ore contains a host of elements which are often unwanted in modern steel.

Silicon

Silica (SiO

2)

is almost always present in iron ore. Most of it is slagged off during

the smelting process. At temperatures above 1,300 °C (2,370 °F) some

will be reduced and form an alloy with the iron. The hotter the furnace,

the more silicon will be present in the iron. It is not uncommon to

find up to 1.5% Si in European cast iron from the 16th to 18th

centuries.

The major effect of silicon is to promote the formation of grey iron. Grey iron is less brittle and easier to finish than white iron. It is preferred for casting purposes for this reason.Turner (1900, pp. 192–197) reported that silicon also reduces shrinkage and the formation of blowholes, lowering the number of bad castings.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) has four major effects on iron: increased hardness and strength, lower solidus temperature, increased fluidity, and cold shortness. Depending on the use intended for the iron, these effects are either good or bad. Bog ore often has a high phosphorus content.

The strength and hardness of iron increases with the concentration of phosphorus. 0.05% phosphorus in wrought iron makes it as hard as medium carbon steel. High phosphorus iron can also be hardened by cold hammering. The hardening effect is true for any concentration of phosphorus. The more phosphorus, the harder the iron becomes and the more it can be hardened by hammering. Modern steel makers can increase hardness by as much as 30%, without sacrificing shock resistance by maintaining phosphorus levels between 0.07 and 0.12%. It also increases the depth of hardening due to quenching, but at the same time also decreases the solubility of carbon in iron at high temperatures. This would decrease its usefulness in making blister steel (cementation), where the speed and amount of carbon absorption is the overriding consideration.

The addition of phosphorus has a down side. At concentrations higher than 0.2% iron becomes increasingly cold short, or brittle at low temperatures. Cold short is especially important for bar iron. Although bar iron is usually worked hot, its uses often require it to be tough, bendable, and resistant to shock at room temperature. A nail that shattered when hit with a hammer or a carriage wheel that broke when it hit a rock would not sell well. High enough concentrations of phosphorus render any iron unusable. The effects of cold shortness are magnified by temperature. Thus, a piece of iron that is perfectly serviceable in summer, might become extremely brittle in winter. There is some evidence that during the Middle Ages the very wealthy may have had a high-phosphorus sword for summer and a low-phosphorus sword for winter.

Careful control of phosphorus can be of great benefit in casting operations. Phosphorus depresses the liquidus temperature, allowing the iron to remain molten for longer and increases fluidity. The addition of 1% can double the distance molten iron will flow. The maximum effect, about 500 °C, is achieved at a concentration of 10.2%. For foundry work Turner felt the ideal iron had 0.2–0.55% phosphorus. The resulting iron filled molds with fewer voids and also shrank less. In the 19th century some producers of decorative cast iron used iron with up to 5% phosphorus. The extreme fluidity allowed them to make very complex and delicate castings. But, they could not be weight bearing, as they had no strength.

There are two remedies for high phosphorus iron. The oldest, easiest and cheapest, is avoidance. If the iron that the ore produced was cold short, one would search for a new source of iron ore. The second method involves oxidizing the phosphorus during the fining process by adding iron oxide. This technique is usually associated with puddling in the 19th century, and may not have been understood earlier. For instance, Isaac Zane, owner of Marlboro Iron Works, did not appear to know about it in 1772. Given Zane's reputation for keeping abreast of the latest developments, the technique was probably unknown to the ironmasters of Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Phosphorus is generally considered to be a deleterious contaminant because it makes steel brittle, even at concentrations of as little as 0.6%. When the Gilchrist–Thomas process allowed to remove bulk amounts of the element from cast iron in the 1870s, it was a major development because most of the iron ores mined in continental Europe at the time were phosphorous. However, removing all the contaminant by fluxing or smelting is complicated, and so desirable iron ores must generally be low in phosphorus to begin with.

Aluminium

Small amounts of aluminium (Al) are present in many ores including iron ore, sand and some limestones. The former can be removed by washing the ore prior to smelting. Until the introduction of brick lined furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination was small enough that it did not have an effect on either the iron or slag. However, when brick began to be used for hearths and the interior of blast furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination increased dramatically. This was due to the erosion of the furnace lining by the liquid slag.

Aluminium is difficult to reduce. As a result, aluminium contamination of the iron is not a problem. However, it does increase the viscosity of the slag. This will have a number of adverse effects on furnace operation. The thicker slag will slow the descent of the charge, prolonging the process. High aluminium will also make it more difficult to tap off the liquid slag. At the extreme this could lead to a frozen furnace.

There are a number of solutions to a high aluminium slag. The first is avoidance; do not use ore or a lime source with a high aluminium content. Increasing the ratio of lime flux will decrease the viscosity.

Sulfur

Sulfur (S) is a frequent contaminant in coal. It is also present in small quantities in many ores, but can be removed by calcining. Sulfur dissolves readily in both liquid and solid iron at the temperatures present in iron smelting. The effects of even small amounts of sulfur are immediate and serious. They were one of the first worked out by iron makers. Sulfur causes iron to be red or hot short.

Hot short iron is brittle when hot. This was a serious problem as most iron used during the 17th and 18th centuries was bar or wrought iron. Wrought iron is shaped by repeated blows with a hammer while hot. A piece of hot short iron will crack if worked with a hammer. When a piece of hot iron or steel cracks the exposed surface immediately oxidizes. This layer of oxide prevents the mending of the crack by welding. Large cracks cause the iron or steel to break up. Smaller cracks can cause the object to fail during use. The degree of hot shortness is in direct proportion to the amount of sulfur present. Today iron with over 0.03% sulfur is avoided.

Hot short iron can be worked, but it has to be worked at low temperatures. Working at lower temperatures requires more physical effort from the smith or forgeman. The metal must be struck more often and harder to achieve the same result. A mildly sulfur contaminated bar can be worked, but it requires a great deal more time and effort.

In cast iron sulfur promotes the formation of white iron. As little as 0.5% can counteract the effects of slow cooling and a high silicon content. White cast iron is more brittle, but also harder. It is generally avoided, because it is difficult to work, except in China where high sulfur cast iron, some as high as 0.57%, made with coal and coke, was used to make bells and chimes. According to Turner (1900, pp. 200), good foundry iron should have less than 0.15% sulfur. In the rest of the world a high sulfur cast iron can be used for making castings, but will make poor wrought iron.

There are a number of remedies for sulfur contamination. The first, and the one most used in historic and prehistoric operations, is avoidance. Coal was not used in Europe (unlike China) as a fuel for smelting because it contains sulfur and therefore causes hot short iron. If an ore resulted in hot short metal, ironmasters looked for another ore. When mineral coal was first used in European blast furnaces in 1709 (or perhaps earlier), it was coked. Only with the introduction of hot blast from 1829 was raw coal used.

Ore roasting

Sulfur can be removed from ores by roasting and washing. Roasting oxidizes sulfur to form sulfur dioxide (SO2) which either escapes into the atmosphere or can be washed out. In warm climates it is possible to leave pyritic ore out in the rain. The combined action of rain, bacteria, and heat oxidize the sulfides to sulfuric acid and sulfates, which are water-soluble and leached out. However, historically (at least), iron sulfide (iron pyrite FeS

2),

though a common iron mineral, has not been used as an ore for the

production of iron metal. Natural weathering was also used in Sweden.

The same process, at geological speed, results in the gossan limonite ores.

The importance attached to low sulfur iron is demonstrated by the consistently higher prices paid for the iron of Sweden, Russia, and Spain from the 16th to 18th centuries. Today sulfur is no longer a problem. The modern remedy is the addition of manganese. But, the operator must know how much sulfur is in the iron because at least five times as much manganese must be added to neutralize it. Some historic irons display manganese levels, but most are well below the level needed to neutralize sulfur.

Sulfide inclusion as manganese sulfide (MnS) can also be the cause of severe pitting corrosion problems in low-grade stainless steel such as AISI 304 steel. Under oxidizing conditions and in the presence of moisture, when sulfide oxidizes it produces thiosulfate anions as intermediate species and because thiosulfate anion has a higher equivalent electromobility than chloride anion due to its double negative electrical charge, it promotes the pit growth. Indeed, the positive electrical charges born by Fe2+ cations released in solution by Fe oxidation on the anodic zone inside the pit must be quickly compensated / neutralised by negative charges brought by the electrokinetic migration of anions in the capillary pit. Some of the electrochemical processes occurring in a capillary pit are the same than these encountered in capillary electrophoresis. Higher the anion electrokinetic migration rate, higher the rate of pitting corrosion. Electrokinetic transport of ions inside the pit can be the rate-limiting step in the pit growth rate.