From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

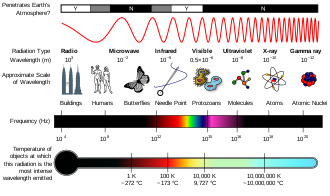

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging from below one hertz to above 1025 hertz, corresponding to wavelengths from thousands of kilometers down to a fraction of the size of an atomic nucleus. This frequency range is divided into separate bands, and the electromagnetic waves

within each frequency band are called by different names; beginning at

the low frequency (long wavelength) end of the spectrum these are: radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays

at the high-frequency (short wavelength) end. The electromagnetic

waves in each of these bands have different characteristics, such as how

they are produced, how they interact with matter, and their practical

applications. There is no known limit for long wavelengths, while it is

thought that the short wavelength limit is in the vicinity of the Planck length. Extreme ultraviolet, soft X-rays, hard X-rays and gamma rays are classified as ionizing radiation as their photons have enough energy to ionize atoms, causing chemical reactions.

In most of the frequency bands above, a technique called spectroscopy can be used to physically separate waves of different frequencies, producing a spectrum showing the constituent frequencies. Spectroscopy is used to study the interactions of electromagnetic waves with matter. Other technological uses are described under electromagnetic radiation.

History and discovery

Humans have always been aware of visible light and radiant heat

but for most of history it was not known that these phenomena were

connected or were representatives of a more extensive principle. The ancient Greeks recognized that light traveled in straight lines and studied some of its properties, including reflection and refraction.

Light was intensively studied from the beginning of the 17th century

leading to the invention of important instruments like the telescope and microscope. Isaac Newton was the first to use the term spectrum for the range of colours that white light could be split into with a prism.

Starting in 1666, Newton showed that these colours were intrinsic to

light and could be recombined into white light. A debate arose over

whether light had a wave nature or a particle nature with René Descartes, Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens

favouring a wave description and Newton favouring a particle

description. Huygens in particular had a well developed theory from

which he was able to derive the laws of reflection and refraction.

Around 1801, Thomas Young measured the wavelength of a light beam with his two-slit experiment thus conclusively demonstrating that light was a wave.

In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation.

He was studying the temperature of different colors by moving a

thermometer through light split by a prism. He noticed that the highest

temperature was beyond red. He theorized that this temperature change

was due to "calorific rays", a type of light ray that could not be seen.

The next year, Johann Ritter,

working at the other end of the spectrum, noticed what he called

"chemical rays" (invisible light rays that induced certain chemical

reactions). These behaved similarly to visible violet light rays, but

were beyond them in the spectrum. They were later renamed ultraviolet radiation.

The study of electromagnetism began in 1820 when Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric currents produce magnetic fields (Oersted's law). Light was first linked to electromagnetism in 1845, when Michael Faraday noticed that the polarization of light traveling through a transparent material responded to a magnetic field (see Faraday effect). During the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell developed four partial differential equations (Maxwell's equations) for the electromagnetic field.

Two of these equations predicted the possibility and behavior of waves

in the field. Analyzing the speed of these theoretical waves, Maxwell

realized that they must travel at a speed that was about the known speed of light.

This startling coincidence in value led Maxwell to make the inference

that light itself is a type of electromagnetic wave. Maxwell's equations

predicted an infinite range of frequencies of electromagnetic waves, all traveling at the speed of light. This was the first indication of the existence of the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Maxwell's predicted waves included waves at very low frequencies

compared to infrared, which in theory might be created by oscillating

charges in an ordinary electrical circuit

of a certain type. Attempting to prove Maxwell's equations and detect

such low frequency electromagnetic radiation, in 1886, the physicist Heinrich Hertz built an apparatus to generate and detect what are now called radio waves.

Hertz found the waves and was able to infer (by measuring their

wavelength and multiplying it by their frequency) that they traveled at

the speed of light. Hertz also demonstrated that the new radiation could

be both reflected and refracted by various dielectric media, in the same manner as light. For example, Hertz was able to focus the waves using a lens made of tree resin. In a later experiment, Hertz similarly produced and measured the properties of microwaves. These new types of waves paved the way for inventions such as the wireless telegraph and the radio.

In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a new type of radiation emitted during an experiment with an evacuated tube subjected to a high voltage. He called this radiation "x-rays"

and found that they were able to travel through parts of the human body

but were reflected or stopped by denser matter such as bones. Before

long, many uses were found for this radiography.

The last portion of the electromagnetic spectrum was filled in with the discovery of gamma rays. In 1900, Paul Villard was studying the radioactive emissions of radium when he identified a new type of radiation that he at first thought consisted of particles similar to known alpha and beta particles, but with the power of being far more penetrating than either. However, in 1910, British physicist William Henry Bragg demonstrated that gamma rays are electromagnetic radiation, not particles, and in 1914, Ernest Rutherford

(who had named them gamma rays in 1903 when he realized that they were

fundamentally different from charged alpha and beta particles) and Edward Andrade measured their wavelengths, and found that gamma rays were similar to X-rays, but with shorter wavelengths.

The wave-particle debate was rekindled in 1901 when Max Planck discovered that light is only absorbed in discrete "quanta", now called photons, implying that light has a particle nature. This idea was made explicit by Albert Einstein

in 1905, but never accepted by Planck and many other contemporaries.

The modern position of science is that electromagnetic radiation has

both a wave and a particle nature, the wave-particle duality. The contradictions arising from this position are still being debated by scientists and philosophers.

Range

Electromagnetic waves are typically described by any of the following three physical properties: the frequency f, wavelength λ, or photon energy E. Frequencies observed in astronomy range from 2.4×1023 Hz (1 GeV gamma rays) down to the local plasma frequency of the ionized interstellar medium (~1 kHz). Wavelength is inversely proportional to the wave frequency, so gamma rays have very short wavelengths that are fractions of the size of atoms,

whereas wavelengths on the opposite end of the spectrum can be

indefinitely long. Photon energy is directly proportional to the wave

frequency, so gamma ray photons have the highest energy (around a

billion electron volts), while radio wave photons have very low energy (around a femtoelectronvolt). These relations are illustrated by the following equations:

where:

Whenever electromagnetic waves exist in a medium with matter,

their wavelength is decreased. Wavelengths of electromagnetic

radiation, whatever medium they are traveling through, are usually

quoted in terms of the vacuum wavelength, although this is not always explicitly stated.

Generally, electromagnetic radiation is classified by wavelength into radio wave, microwave, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. The behavior of EM radiation depends on its wavelength. When EM radiation interacts with single atoms and molecules, its behavior also depends on the amount of energy per quantum (photon) it carries.

Spectroscopy can detect a much wider region of the EM spectrum than the visible wavelength range of 400 nm to 700 nm in a vacuum. A common laboratory spectroscope can detect wavelengths from 2 nm to 2500 nm.

Detailed information about the physical properties of objects, gases,

or even stars can be obtained from this type of device. Spectroscopes

are widely used in astrophysics. For example, many hydrogen atoms emit a radio wave photon that has a wavelength of 21.12 cm. Also, frequencies of 30 Hz and below can be produced by and are important in the study of certain stellar nebulae and frequencies as high as 2.9×1027 Hz have been detected from astrophysical sources.

Regions

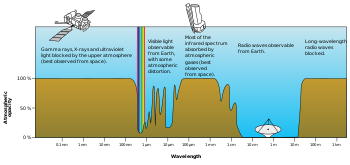

The electromagnetic spectrum

A diagram of the electromagnetic spectrum, showing various properties across the range of frequencies and wavelengths

The types of electromagnetic radiation are broadly classified into the following classes (regions, bands or types):

- Gamma radiation

- X-ray radiation

- Ultraviolet radiation

- Visible light

- Infrared radiation

- Microwave radiation

- Radio waves

This classification goes in the increasing order of wavelength, which is characteristic of the type of radiation.

There are no precisely defined boundaries between the bands of

the electromagnetic spectrum; rather they fade into each other like the

bands in a rainbow

(which is the sub-spectrum of visible light). Radiation of each

frequency and wavelength (or in each band) has a mix of properties of

the two regions of the spectrum that bound it. For example, red light

resembles infrared radiation in that it can excite and add energy to

some chemical bonds and indeed must do so to power the chemical mechanisms responsible for photosynthesis and the working of the visual system.

The distinction between X-rays and gamma rays is partly based on sources: the photons generated from nuclear decay or other nuclear and subnuclear/particle process are always termed gamma rays, whereas X-rays are generated by electronic transitions involving highly energetic inner atomic electrons.

In general, nuclear transitions are much more energetic than electronic

transitions, so gamma rays are more energetic than X-rays, but

exceptions exist. By analogy to electronic transitions, muonic atom transitions are also said to produce X-rays, even though their energy may exceed 6 megaelectronvolts (0.96 pJ), whereas there are many (77 known to be less than 10 keV (1.6 fJ)) low-energy nuclear transitions (e.g., the 7.6 eV (1.22 aJ) nuclear transition of thorium-229m),

and, despite being one million-fold less energetic than some muonic

X-rays, the emitted photons are still called gamma rays due to their

nuclear origin.

The convention that EM radiation that is known to come from the

nucleus is always called "gamma ray" radiation is the only convention

that is universally respected, however. Many astronomical gamma ray sources (such as gamma ray bursts) are known to be too energetic (in both intensity and wavelength) to be of nuclear origin. Quite often, in high-energy physics and in medical radiotherapy,

very high energy EMR (in the > 10 MeV region)—which is of higher

energy than any nuclear gamma ray—is not called X-ray or gamma ray, but

instead by the generic term of "high-energy photons".

The region of the spectrum where a particular observed electromagnetic radiation falls is reference frame-dependent (due to the Doppler shift

for light), so EM radiation that one observer would say is in one

region of the spectrum could appear to an observer moving at a

substantial fraction of the speed of light with respect to the first to

be in another part of the spectrum. For example, consider the cosmic microwave background. It was produced when matter and radiation decoupled, by the de-excitation of hydrogen atoms to the ground state. These photons were from Lyman series

transitions, putting them in the ultraviolet (UV) part of the

electromagnetic spectrum. Now this radiation has undergone enough

cosmological red shift

to put it into the microwave region of the spectrum for observers

moving slowly (compared to the speed of light) with respect to the

cosmos.

Rationale for names

Electromagnetic

radiation interacts with matter in different ways across the spectrum.

These types of interaction are so different that historically different

names have been applied to different parts of the spectrum, as though

these were different types of radiation. Thus, although these "different

kinds" of electromagnetic radiation form a quantitatively continuous

spectrum of frequencies and wavelengths, the spectrum remains divided

for practical reasons related to these qualitative interaction

differences.

Electromagnetic radiation interaction with matter

| Region of the spectrum

|

Main interactions with matter

|

| Radio

|

Collective oscillation of charge carriers in bulk material (plasma oscillation). An example would be the oscillatory travels of the electrons in an antenna.

|

| Microwave through far infrared

|

Plasma oscillation, molecular rotation

|

| Near infrared

|

Molecular vibration, plasma oscillation (in metals only)

|

| Visible

|

Molecular electron excitation (including pigment molecules found in the human retina), plasma oscillations (in metals only)

|

| Ultraviolet

|

Excitation of molecular and atomic valence electrons, including ejection of the electrons (photoelectric effect)

|

| X-rays

|

Excitation and ejection of core atomic electrons, Compton scattering (for low atomic numbers)

|

| Gamma rays

|

Energetic ejection of core electrons in heavy elements, Compton

scattering (for all atomic numbers), excitation of atomic nuclei,

including dissociation of nuclei

|

| High-energy gamma rays

|

Creation of particle-antiparticle pairs.

At very high energies a single photon can create a shower of

high-energy particles and antiparticles upon interaction with matter.

|

Types of radiation

Radio waves

Radio waves are emitted and received by antennas, which consist of conductors such as metal rod resonators. In artificial generation of radio waves, an electronic device called a transmitter generates an AC electric current which is applied to an antenna. The oscillating electrons in the antenna generate oscillating electric and magnetic fields

that radiate away from the antenna as radio waves. In reception of

radio waves, the oscillating electric and magnetic fields of a radio

wave couple to the electrons in an antenna, pushing them back and forth,

creating oscillating currents which are applied to a radio receiver. Earth's atmosphere is mainly transparent to radio waves, except for layers of charged particles in the ionosphere which can reflect certain frequencies.

Radio waves are extremely widely used to transmit information across distances in radio communication systems such as radio broadcasting, television, two way radios, mobile phones, communication satellites, and wireless networking. In a radio communication system, a radio frequency current is modulated with an information-bearing signal

in a transmitter by varying either the amplitude, frequency or phase,

and applied to an antenna. The radio waves carry the information across

space to a receiver, where they are received by an antenna and the

information extracted by demodulation in the receiver. Radio waves are also used for navigation in systems like Global Positioning System (GPS) and navigational beacons, and locating distant objects in radiolocation and radar. They are also used for remote control, and for industrial heating.

The use of the radio spectrum is strictly regulated by governments, coordinated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) which allocates frequencies to different users for different uses.

Microwaves

Plot

of Earth's atmospheric opacity to various wavelengths of

electromagnetic radiation. This is the surface-to-space opacity, the

atmosphere is transparent to

longwave radio transmissions within the

troposphere but opaque to space due to the

ionosphere.

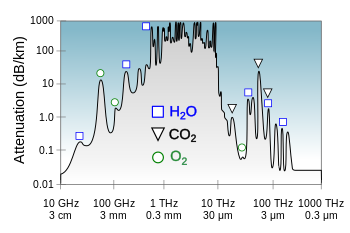

Plot

of atmospheric opacity for terrestial to terrestial transmission

showing the molecules responsible for some of the resonances

Microwaves are radio waves of short wavelength, from about 10 centimeters to one millimeter, in the SHF and EHF frequency bands. Microwave energy is produced with klystron and magnetron tubes, and with solid state devices such as Gunn and IMPATT diodes. Although they are emitted and absorbed by short antennas, they are also absorbed by polar molecules, coupling to vibrational and rotational modes, resulting in bulk heating. Unlike higher frequency waves such as infrared and light

which are absorbed mainly at surfaces, microwaves can penetrate into

materials and deposit their energy below the surface. This effect is

used to heat food in microwave ovens, and for industrial heating and medical diathermy. Microwaves are the main wavelengths used in radar, and are used for satellite communication, and wireless networking technologies such as Wi-Fi. The copper cables (transmission lines)

which are used to carry lower frequency radio waves to antennas have

excessive power losses at microwave frequencies, and metal pipes called waveguides

are used to carry them. Although at the low end of the band the

atmosphere is mainly transparent, at the upper end of the band

absorption of microwaves by atmospheric gasses limits practical

propagation distances to a few kilometers.

Terahertz radiation

or sub-millimeter radiation is a region of the spectrum from about

100 GHz to 30 terahertz (THz) between microwaves and far infrared which

can be regarded as belonging to either band. Until recently, the range

was rarely studied and few sources existed for microwave energy in the

so-called terahertz gap,

but applications such as imaging and communications are now appearing.

Scientists are also looking to apply terahertz technology in the armed

forces, where high-frequency waves might be directed at enemy troops to

incapacitate their electronic equipment.

Terahertz radiation is strongly absorbed by atmospheric gases, making

this frequency range useless for long-distance communication.

Infrared radiation

The infrared

part of the electromagnetic spectrum covers the range from roughly

300 GHz to 400 THz (1 mm – 750 nm). It can be divided into three parts:

- Far-infrared, from 300 GHz to 30 THz (1 mm – 10 μm). The

lower part of this range may also be called microwaves or terahertz

waves. This radiation is typically absorbed by so-called rotational

modes in gas-phase molecules, by molecular motions in liquids, and by phonons

in solids. The water in Earth's atmosphere absorbs so strongly in this

range that it renders the atmosphere in effect opaque. However, there

are certain wavelength ranges ("windows") within the opaque range that

allow partial transmission, and can be used for astronomy. The

wavelength range from approximately 200 μm up to a few mm is often

referred to as Submillimetre astronomy, reserving far infrared for wavelengths below 200 μm.

- Mid-infrared, from 30 to 120 THz (10–2.5 μm). Hot objects (black-body

radiators) can radiate strongly in this range, and human skin at normal

body temperature radiates strongly at the lower end of this region.

This radiation is absorbed by molecular vibrations, where the different

atoms in a molecule vibrate around their equilibrium positions. This

range is sometimes called the fingerprint region, since the mid-infrared absorption spectrum of a compound is very specific for that compound.

- Near-infrared, from 120 to 400 THz (2,500–750 nm). Physical

processes that are relevant for this range are similar to those for

visible light. The highest frequencies in this region can be detected

directly by some types of photographic film, and by many types of solid

state image sensors for infrared photography and videography.

Visible light

|

|

| Color

|

Wavelength

(nm)

|

Frequency

(THz)

|

Photon energy

(eV)

|

|

|

380–450

|

670–790

|

2.75–3.26

|

|

|

450–485

|

620–670

|

2.56–2.75

|

|

|

485–500

|

600–620

|

2.48–2.56

|

|

|

500–565

|

530–600

|

2.19–2.48

|

|

|

565–590

|

510–530

|

2.10–2.19

|

|

|

590–625

|

480–510

|

1.98–2.10

|

|

|

625–750

|

400–480

|

1.65–1.98

|

Above infrared in frequency comes visible light. The Sun

emits its peak power in the visible region, although integrating the

entire emission power spectrum through all wavelengths shows that the

Sun emits slightly more infrared than visible light. By definition, visible light is the part of the EM spectrum the human eye

is the most sensitive to. Visible light (and near-infrared light) is

typically absorbed and emitted by electrons in molecules and atoms that

move from one energy level to another. This action allows the chemical

mechanisms that underlie human vision and plant photosynthesis. The

light that excites the human visual system is a very small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. A rainbow

shows the optical (visible) part of the electromagnetic spectrum;

infrared (if it could be seen) would be located just beyond the red side

of the rainbow whilst ultraviolet would appear just beyond the opposite violet end.

Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength between 380 nm

and 760 nm (400–790 terahertz) is detected by the human eye and

perceived as visible light. Other wavelengths, especially near infrared

(longer than 760 nm) and ultraviolet (shorter than 380 nm) are also

sometimes referred to as light, especially when the visibility to humans

is not relevant. White light is a combination of lights of different

wavelengths in the visible spectrum. Passing white light through a prism

splits it up into the several colors of light observed in the visible

spectrum between 400 nm and 780 nm.

If radiation having a frequency in the visible region of the EM

spectrum reflects off an object, say, a bowl of fruit, and then strikes

the eyes, this results in visual perception

of the scene. The brain's visual system processes the multitude of

reflected frequencies into different shades and hues, and through this

insufficiently-understood psychophysical phenomenon, most people

perceive a bowl of fruit.

At most wavelengths, however, the information carried by

electromagnetic radiation is not directly detected by human senses.

Natural sources produce EM radiation across the spectrum, and technology

can also manipulate a broad range of wavelengths. Optical fiber

transmits light that, although not necessarily in the visible part of

the spectrum (it is usually infrared), can carry information. The

modulation is similar to that used with radio waves.

Ultraviolet radiation

The amount of penetration of UV relative to altitude in Earth's

ozoneNext in frequency comes ultraviolet (UV). The wavelength of UV rays is shorter than the violet end of the visible spectrum but longer than the X-ray.

UV is the longest wavelength radiation whose photons are energetic enough to ionize atoms, separating electrons from them, and thus causing chemical reactions. Short wavelength UV and the shorter wavelength radiation above it (X-rays and gamma rays) are called ionizing radiation,

and exposure to them can damage living tissue, making them a health

hazard. UV can also cause many substances to glow with visible light;

this is called fluorescence.

At the middle range of UV, UV rays cannot ionize but can break chemical bonds, making molecules unusually reactive. Sunburn, for example, is caused by the disruptive effects of middle range UV radiation on skin cells, which is the main cause of skin cancer. UV rays in the middle range can irreparably damage the complex DNA molecules in the cells producing thymine dimers making it a very potent mutagen.

The Sun emits significant UV radiation (about 10% of its total

power), including extremely short wavelength UV that could potentially

destroy most life on land (ocean water would provide some protection for

life there). However, most of the Sun's damaging UV wavelengths are

absorbed by the atmosphere before they reach the surface. The higher

energy (shortest wavelength) ranges of UV (called "vacuum UV") are

absorbed by nitrogen and, at longer wavelengths, by simple diatomic oxygen

in the air. Most of the UV in the mid-range of energy is blocked by the

ozone layer, which absorbs strongly in the important 200–315 nm range,

the lower energy part of which is too long for ordinary dioxygen

in air to absorb. This leaves less than 3% of sunlight at sea level in

UV, with all of this remainder at the lower energies. The remainder is

UV-A, along with some UV-B. The very lowest energy range of UV between

315 nm and visible light (called UV-A) is not blocked well by the

atmosphere, but does not cause sunburn and does less biological damage.

However, it is not harmless and does create oxygen radicals, mutations

and skin damage.

X-rays

After UV come X-rays,

which, like the upper ranges of UV are also ionizing. However, due to

their higher energies, X-rays can also interact with matter by means of

the Compton effect.

Hard X-rays have shorter wavelengths than soft X-rays and as they can

pass through many substances with little absorption, they can be used to

'see through' objects with 'thicknesses' less than that equivalent to a

few meters of water. One notable use is diagnostic X-ray imaging in

medicine (a process known as radiography). X-rays are useful as probes in high-energy physics. In astronomy, the accretion disks around neutron stars and black holes emit X-rays, enabling studies of these phenomena. X-rays are also emitted by stellar corona and are strongly emitted by some types of nebulae. However, X-ray telescopes must be placed outside the Earth's atmosphere to see astronomical X-rays, since the great depth of the atmosphere of Earth is opaque to X-rays (with areal density of 1000 g/cm2), equivalent to 10 meters thickness of water. This is an amount sufficient to block almost all astronomical X-rays (and also astronomical gamma rays—see below).

Gamma rays

After hard X-rays come gamma rays, which were discovered by Paul Ulrich Villard in 1900. These are the most energetic photons, having no defined lower limit to their wavelength. In astronomy

they are valuable for studying high-energy objects or regions, however

as with X-rays this can only be done with telescopes outside the Earth's

atmosphere. Gamma rays are used experimentally by physicists for their

penetrating ability and are produced by a number of radioisotopes. They are used for irradiation of foods and seeds for sterilization, and in medicine they are occasionally used in radiation cancer therapy. More commonly, gamma rays are used for diagnostic imaging in nuclear medicine, an example being PET scans. The wavelength of gamma rays can be measured with high accuracy through the effects of Compton scattering.