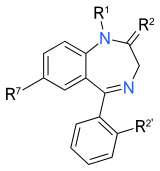

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

The core structure of benzodiazepines. "R" labels denote common locations of side chains, which give different benzodiazepines their unique properties.

|

| Benzodiazepine dependence | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | psychiatry |

| ICD-10 | F13.1 |

Some of the symptoms that could possibly occur as a result of a withdrawal from benzodiazepines after long-term use include emotional clouding,[1] flu-like symptoms,[4] suicide,[7] nausea, headaches, dizziness, irritability, lethargy, sleep problems, memory impairment, personality changes, aggression, depression, social deterioration as well as employment difficulties, while others never have any side effects from long-term benzodiazepine use. One should never abruptly stop using this medicine and should wean themself down to a lower dose under doctor supervision.[8][9][10] While benzodiazepines are highly effective in the short term, adverse effects in some people associated with long-term use including impaired cognitive abilities, memory problems, mood swings, and overdoses when combined with other drugs may make the risk-benefit ratio unfavourable, while others experience no ill effects. In addition, benzodiazepines have reinforcing properties in some individuals and thus are considered to be addictive drugs, especially in individuals that have a "drug-seeking" behavior; further, a physical dependence can develop after a few weeks or months of use.[11] Many of these adverse effects of long-term use of benzodiazepines begin to show improvements three to six months after withdrawal.[12][13]

Other concerns about the effects of long-term benzodiazepine use, in some, include dose escalation, benzodiazepine abuse, tolerance and benzodiazepine dependence and benzodiazepine withdrawal problems. Both physiological tolerance and dependence can lead to a worsening of the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. Increased risk of death has been associated with long-term use of benzodiazepines in several studies; however, other studies have not found increased mortality. Due to conflicting findings in studies regarding benzodiazepines and increased risks of death including from cancer, further research in long-term use of benzodiazepines and mortality risk has been recommended. Most of the research has been conducted in prescribed users of benzodiazepines; but regarding the mortality, its been proven by a study to have an increase in prescribed users in the past decade[when?] and a half and 75% of the deaths associated with it happened in the last four years.[14][15] The long-term use of benzodiazepines is controversial and has generated significant controversy within the medical profession. Views on the nature and severity of problems with long-term use of benzodiazepines differ from expert to expert and even from country to country; some experts even question whether there is any problem with the long-term use of benzodiazepines.[16]

Symptoms

Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use may include disinhibition, impaired concentration and memory, depression,[17][18] as well as sexual dysfunction.[5][19] The long-term effects of benzodiazepines may differ from the adverse effects seen after acute administration of benzodiazepines.[20] An analysis of cancer patients found that those who took tranquillisers or sleeping tablets had a substantially poorer quality of life on all measurements conducted, as well as a worse clinical picture of symptomatology. Worsening of symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, pain, dyspnea and constipation was found when compared against those who did not take tranquillisers or sleeping tablets.[21] Most individuals who successfully discontinue hypnotic therapy after a gradual taper and do not take benzodiazepines for 6 months have less severe sleep and anxiety problems, are less distressed and have a general feeling of improved health at 6-month follow-up.[13] The use of benzodiazepines for the treatment of anxiety has been found to lead to a significant increase in healthcare costs due to accidents and other adverse effects associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines.[22][medical citation needed]Cognitive status

Long-term benzodiazepine use can lead to a generalised impairment of cognition, including sustained attention, verbal learning and memory and psychomotor, visuo-motor and visuo-conceptual abilities.[23][24] These effects on cognition exist, although their impact on a patient's daily functioning is, in most (but not all cases), insignificant. Transient changes in the brain have been found using neuroimaging studies, but no brain abnormalities have been found in patients treated long term with benzodiazepines.[25] When benzodiazepine users cease long-term benzodiazepine therapy, their cognitive function improves in the first six months, although deficits may be permanent or take longer than six months to return to baseline.[26][27] In the elderly, long-term benzodiazepine therapy is a risk factor for amplifying cognitive decline,[28] although gradual withdrawal is associated with improved cognitive status.[29] A study of alprazolam found that 8 weeks administration of alprazolam resulted in deficits that were detectable after several weeks but not after 3–5 years.Effect on sleep

Sleep architecture can be adversely affected by benzodiazepine dependence. Possible adverse effects on sleep include induction or worsening of sleep disordered breathing. Like alcohol, benzodiazepines are commonly used to treat insomnia in the short term (both prescribed and self-medicated), but worsen sleep in the long term. (Need citation.) Although benzodiazepines can put people to sleep, while asleep, the drugs disrupt sleep architecture: decreasing sleep time, delaying time to and decreased REM sleep, increasing alpha and beta activity, decreasing K complexes and delta activity, and decreasing deep slow-wave sleep (i.e., NREM stages 3 and 4, the most restorative part of sleep for both energy and mood).[31][32][33][34]Mental and physical health

The long-term use of benzodiazepines may have a similar effect on the brain as alcohol, and are also implicated in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mania, psychosis, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, delirium, and neurocognitive disorders.[35][36] However a 2016 study found no association between long-term usage and dementia.[37] As with alcohol, the effects of benzodiazepine on neurochemistry, such as decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, are believed to be responsible for their effects on mood and anxiety.[38][39][40][41][42][43] Additionally, benzodiazepines can indirectly cause or worsen other psychiatric symptoms (e.g., mood, anxiety, psychosis, irritability) by worsening sleep (i.e., benzodiazepine-induced sleep disorder).Long-term benzodiazepine use may lead to the creation or exacerbation of physical and mental health conditions, which improve after 6 or more months of abstinence. After a period of about 3 to 6 months of abstinence after completion of a gradual-reduction regimen, marked improvements in mental and physical wellbeing become apparent. For example, one study of hypnotic users gradually withdrawn from their hypnotic medication reported after 6 months of abstinence that they had less severe sleep and anxiety problems, were less distressed, and had a general feeling of improved health. Those having remained on hypnotic medication had no improvements in their insomnia, anxiety, or general health ratings.[13] A study found that individuals having withdrawn from benzodiazepines showed a marked reduction in use of medical and mental health services.[44][medical citation needed]

Approximately half of patients attending mental health services for conditions including anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or social phobia may be the result of alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence.[45] Sometimes anxiety disorders precede alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence but the alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence often acts to keep the anxiety disorders going and often progressively makes them worse.[45][medical citation needed] Many people who are addicted to alcohol or prescribed benzodiazepines decide to quit when it is explained to them they have a choice between ongoing ill mental health or quitting and recovering from their symptoms. It was noted that because every individual has an individual sensitivity level to alcohol or sedative hypnotic drugs, what one person can tolerate without ill health will cause another to suffer very ill health, and that even moderate drinking in sensitive individuals can cause rebound anxiety syndromes and sleep disorders. A person who is suffering the toxic effects of alcohol or benzodiazepines will not benefit from other therapies or medications as they do not address the root cause of the symptoms. Recovery from benzodiazepine dependence tends to take a lot longer than recovery from alcohol but people can regain their previous good health.[45] A review of the literature regarding benzodiazepine hypnotic drugs concluded that these drugs cause an unjustifiable risk to the individual and to public health. The risks include dependence, accidents and other adverse effects. Gradual discontinuation of hypnotics leads to improved health without worsening of sleep.[46]

Daily users of benzodiazepines are also at a higher risk of experiencing psychotic symptomatology such as delusions and hallucinations.[47] A study found that of 42 patients treated with alprazolam, up to a third of long-term users of the benzodiazepine drug alprazolam (Xanax) develop depression.[48] Studies have shown that long-term use of benzodiazepines and the benzodiazepine receptor agonist nonbenzodiazepine Z drugs are associated with causing depression as well as a markedly raised suicide risk and an overall increased mortality risk.[49][50]

A study of 50 patients who attended a benzodiazepine withdrawal clinic found that long-term use of benzodiazepines causes a wide range of psychological and physiological disorders. It was found that, after several years of chronic benzodiazepine use, a large portion of patients developed various mental and physical health problems including agoraphobia, irritable bowel syndrome, paraesthesiae, increasing anxiety, and panic attacks, which were not preexisting. The mental health and physical health symptoms induced by long-term benzodiazepine use gradually improved significantly over a period of a year following completion of a slow withdrawal. Three of the 50 patients had wrongly been given a preliminary diagnosis of multiple sclerosis when the symptoms were actually due to chronic benzodiazepine use. Ten of the patients had taken drug overdoses whilst on benzodiazepines, despite the fact that only two of the patients had any prior history of depressive symptomatology. After withdrawal, no patients took any further overdoses after 1 year post-withdrawal. The cause of the deteriorating mental and physical health in a significant proportion of patients was hypothesised to be caused by increasing tolerance where withdrawal-type symptoms emerged, despite the administration of stable prescribed doses.[51] Another theory is that chronic benzodiazepine use causes subtle increasing toxicity, which in turn leads to increasing psychopathology in long-term users of benzodiazepines.[52]

Long-term use of benzodiazepines can induce perceptual disturbances and depersonalisation in some people, even in those taking a stable daily dosage, and it can also become a protracted withdrawal feature of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[53]

In addition, chronic use of benzodiazepines is a risk factor for blepharospasm.[54] Drug-induced symptoms that resemble withdrawal-like effects can occur on a set dosage as a result of prolonged use, also documented with barbiturate-like substances, as well as alcohol and benzodiazepines. This demonstrates that the effects from chronic use of benzodiazepine drugs is not unique but occurs with other GABAergic sedative hypnotic drugs, i.e., alcohol and barbiturates.[55]

Immune system

Chronic use of benzodiazepines seemed to cause significant immunological disorders in a study of selected outpatients attending a psychopharmacology department.[56] Diazepam and clonazepam have been found to have long-lasting, but not permanent, immunotoxic effects in the fetus of pregnant rats. However, single very high doses of diazepam have been found to cause lifelong immunosuppression in neonatal rats. No studies have been done to assess the immunotoxic effects of diazepam in humans; however, high prescribed doses of diazepam, in humans, has been found to be a major risk of pneumonia, based on a study of people with tetanus. It has been proposed that diazepam may cause long-lasting changes to the GABAA receptors with resultant long-lasting disturbances to behaviour, endocrine function and immune function.[57]Suicide and self-harm

Use of prescribed benzodiazepines is associated with an increased rate of attempted and completed suicide. The prosuicidal effects of benzodiazepines are suspected to be due to a psychiatric disturbance caused by side effects or withdrawal symptoms.[7] Because benzodiazepines in general may be associated with increased suicide risk, care should be taken when prescribing, especially to at-risk patients.[58][59] Depressed adolescents who were taking benzodiazepines were found to have a greatly increased risk of self-harm or suicide, although the sample size was small. The effects of benzodiazepines in individuals under the age of 18 requires further research. Additional caution is required in using benzodiazepines in depressed adolescents.[60] Benzodiazepine dependence often results in an increasingly deteriorating clinical picture, which includes social deterioration leading to comorbid alcoholism and drug abuse. Benzodiazepine misuse or misuse of other CNS depressants increases the risk of suicide in drug misusers.[61][62] Benzodiazepine has several risks based on its biochemical function and symptoms associated with this medication like exacerbation of sleep apnea, sedation, suppression of self-care functions, amnesia and disinhibition are suggested as a possible explanation to the increase in mortality. Studies also demonstrate that an increased mortality associated with benzodiazepine use has been clearly documented among ‘drug misusers’.[63]Carcinogenicity

There has been some controversy around the possible link between benzodiazepine use and development of cancer; early cohort studies in the 1980s suggested a possible link, but follow-up case-control studies have found no link between benzodiazepines and cancer. In the second U.S. national cancer study in 1982, the American Cancer Society conducted a survey of over 1.1 million participants. A marked increased risk of cancer was found in the users of sleeping pills, mainly benzodiazepines.[64] There have been 15 epidemiologic studies that have suggested that benzodiazepine or nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drug use is associated with increased mortality, mainly due to increased cancer deaths in humans. The cancers included cancer of the brain, lung, bowel, breast, and bladder, and other neoplasms. It has been hypothesised that either depressed immune function or the viral infections themselves were the cause of the increased rates of cancer. While initially U.S. Food and Drug Administration reviewers expressed concerns about approving the nonbenzodiazepine Z drugs due to concerns of cancer, ultimately they changed their minds and approved the drugs.[65] A recent case-control study, however, found no link between use of benzodiazepines and cancers of the breast, lung, large bowel, lung, uterine lining, ovaries, testes, thyroid, liver, or Hodgkin's Disease, melanoma, or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.[66] More specific case-control studies since 2000 have shown no link between benzodiazepine use and breast cancer.[67] One study found an association between self-reported benzodiazepine use and development of ovarian cancer, whereas another study found no relationship.[68][69] A 2016 meta-analysis of multiple observational studies found that benzodiazepine use is associated with increased cancer risk.[70]Brain damage evidence

In a study in 1980 in a group of 55 consecutively admitted patients having abused exclusively sedatives or hypnotics, neuropsychological performance was significantly lower and signs of intellectual impairment significantly more often diagnosed than in a matched control group taken from the general population. These results suggested a relationship between abuse of sedatives or hypnotics and cerebral disorder.[71]A publication has asked in 1981 if lorazepam is more toxic than diazepam.[72]

In a study in 1984, 20 patients having taken long-term benzodiazepines were submitted to brain CT scan examinations. Some scans appeared abnormal. The mean ventricular-brain ratio measured by planimetry was increased over mean values in an age- and sex-matched group of control subjects but was less than that in a group of alcoholics. There was no significant relationship between CT scan appearances and the duration of benzodiazepine therapy. The clinical significance of the findings was unclear.[73]

In 1986, it was presumed that permanent brain damage may result from chronic use of benzodiazepines similar to alcohol-related brain damage.[74]

In 1987, 17 high-dose inpatient abusers of benzodiazepines have anecdotally shown enlarged cerebrospinal fluid spaces with associated brain shrinkage. Brain shrinkage reportedly appeared to be dose dependent with low-dose users having less brain shrinkage than higher-dose users.[75]

However, a CT study in 1987 found no evidence of brain shrinkage in prescribed benzodiazepine users.[76]

In 1989, in a 4- to 6-year follow-up study of 30 inpatient benzodiazepine abusers, Neuropsychological function was found to be permanently affected in some chronic high-dose abusers of benzodiazepines. Brain damage similar to alcoholic brain damage was observed. The CT scan abnormalities showed dilatation of the ventricular system. However, unlike alcoholics, sedative hypnotic abusers showed no evidence of widened cortical sulci. The study concluded that, when cerebral disorder is diagnosed in sedative hypnotic benzodiazepine abusers, it is often permanent.[77]

A CT study in 1993 investigated brain damage in benzodiazepine users and found no overall differences to a healthy control group.[78]

A study in 2000 found that long-term benzodiazepine therapy does not result in brain abnormalities.[79]

Withdrawal from high-dose abuse of nitrazepam anecdotally was alleged in 2001 to have caused severe shock of the whole brain with diffuse slow activity on EEG in one patient after 25 years of abuse. After withdrawal, abnormalities in hypofrontal brain wave patterns persisted beyond the withdrawal syndrome, which suggested to the authors that organic brain damage occurred from chronic high-dose abuse of nitrazepam.[80]

Professor Heather Ashton, a leading expert on benzodiazepines from Newcastle University Institute of Neuroscience, has stated that there is no structural damage from benzodiazepines, and advocates for further research into long-lasting or possibly permanent symptoms of long-term use of benzodiazepines as of 1996.[81] She has stated that she believes that the most likely explanation for lasting symptoms is persisting but slowly resolving functional changes at the GABAA benzodiazepine receptor level. Newer and more detailed brain scanning technologies such as PET scans and MRI scans had as of 2002 to her knowledge never been used to investigate the question of whether benzodiazepines cause functional or structural brain damage.[82]

In 2014 studies have found an association between the use of benzodiazepines and an increased risk of dementia but the exact nature of the relationship is still a matter of debate.[83] A later study found no such effects.[37]

History

Benzodiazepines when introduced in 1961 were widely believed to be safe drugs but as the decades went by increased awareness of adverse effects connected to their long-term use became known. There was initially widespread public approval but this was followed by widespread public disapproval, and recommendations for more restrictive medical guidelines followed.[84][85] Concerns regarding the long-term effects of benzodiazepines have been raised since 1980.[86] These concerns are still not fully answered. A review in 2006 of the literature on use of benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of hypnotic drugs.[87] The majority of the problems of benzodiazepines are related to their long-term use rather than their short-term use.[88] There is growing evidence of the harm of long-term use of benzodiazepines, especially at higher doses. In 2007, the Department of Health recommended that individuals on long-term benzodiazepines be monitored at least every 3 months and also recommended against long-term substitution therapy in benzodiazepine drug misusers due to a lack of evidence base for effectiveness and due to the risks of long-term use.[89] The long-term effects of benzodiazepines are very similar to the long-term effects of alcohol (apart from organ toxicity) and other sedative-hypnotics. Withdrawal effects and dependence are almost identical. A report in 1987 by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Great Britain reported that any benefits of long-term use of benzodiazepines are likely to be far outweighed by the risks of long-term use.[90] Despite this benzodiazepines are still widely prescribed. The socioeconomic costs of the continued widespread prescribing of benzodiazepines is high.[91]Political controversy

In 1980, the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) recommended that research be conducted into the effects of long-term use of benzodiazepines[92] A 2009 British Government parliamentary inquiry recommended that research into the long-term effects of benzodiazepines must be carried out.[93] The view of the Department of Health is that they have made every effort to make doctors aware of the problems associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines,[94] as well as the dangers of benzodiazepine drug addiction.[95]In 1980, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency's Committee on the Safety of Medicines issued guidance restricting the use of benzodiazepines to short-term use and updated and strengthened these warnings in 1988. When asked by Phil Woolas in 1999 whether the Department of Health had any plans to conduct research into the long-term effects of benzodiazepines, the Department replied, saying they have no plans to do so, as benzodiazepines are already restricted to short-term use and monitored by regulatory bodies.[96] In a House of Commons debate, Phil Woolas has claimed that there has been a cover-up with regard to the problems associated with benzodiazepines because they are of too large of a scale for governments, regulatory bodies, and the pharmaceutical industry to deal with. John Hutton stated in response that the Department of Health take the problems of benzodiazepines extremely seriously and are not sweeping the issue under the carpet.[97] In 2010, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Involuntary Tranquilliser Addiction filed a complaint with the Equality and Human Rights Commission under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 against the Department of Health and the Department for Work and Pensions alleging discrimation against people with a benzodiazepine prescription drug dependence as a result of denial of specialised treatment services, exclusion from medical treatment, non-recognition of the protracted benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, as well as denial of rehabilitation and back-to-work schemes. Additionally the APPGITA complaint alleged that there is a "virtual prohibition" on the collection of statistical information on benzodiazepines across government departments, whereas with other controlled drugs there are enormous volumes of statistical data. The complaint alleged that the discrimination is deliberate, large scale and that government departments are aware of what they are doing.[98]

Declassified Medical Research Council meeting

The Medical Research Council (UK) held a closed meeting among top UK medical doctors and representatives from the pharmaceutical industry between the dates of 30 October 1980 and 3 April 1981. The meeting was classified under the Public Records Act 1958 until 2014 but became available in 2005 as a result of the Freedom of Information Act. The meeting was called due to concerns that 10–100,000 people could be dependent; meeting chairman Professor Malcolm Lader later revised this estimate to include approximately half a million members of the British public suspected of being dependent on therapeutic dose levels of benzodiazepines, with about half of those on long-term benzodiazepines. It was reported that benzodiazepines may be the third- or fourth-largest drug problem in the UK (the largest being alcohol and tobacco). The Chairman of the meeting followed up after the meeting with additional information, which was forwarded to the Medical Research Council neuroscience board, raising concerns regarding tests that showed definite cortical atrophy in 2 of 14 individuals tested and borderline abnormality in five others. He felt that, due to the methodology used in assessing the scans, the abnormalities were likely an underestimate, and more refined techniques would be more accurate. Also discussed were findings that tolerance to benzodiazepines can be demonstrated by injecting diazepam into long-term users; in normal subjects, increases in growth hormone occurs, whereas in benzodiazepine-tolerant individuals this effect is blunted. Also raised were findings in animal studies that showed the development of tolerance in the form of a 15 percent reduction in binding capacity of benzodiazepines after seven days administration of high doses of the partial agonist benzodiazepine drug flurazepam and a 50 percent reduction in binding capacity after 30 days of a low dose of diazepam. The Chairman was concerned that papers soon to be published would "stir the whole matter up" and wanted to be able to say that the Medical Research Council "had matters under consideration if questions were asked in parliament". The Chairman felt that it "was very important, politically that the MRC should be 'one step ahead'" and recommended epidemiological studies be funded and carried out by Roche Pharmaceuticals and MRC sponsored research conducted into the biochemical effects of long-term use of benzodiazepines. The meeting aimed to identify issues that were likely to arise, alert the Department of Health to the scale of the problem and identify the pharmacology and nature of benzodiazepine dependence and the volume of benzodiazepines being prescribed. The World Health Organisation was also interested in the problem and it was felt the meeting would demonstrate to the WHO that the MRC was taking the issue seriously. Among the psychological effects of long-term use of benzodiazepines discussed was a reduced ability to cope with stress. The Chairman stated that the "withdrawal symptoms from valium were much worse than many other drugs including, e.g., heroin". It was stated that the likelihood of withdrawing from benzodiazepines was "reduced enormously" if benzodiazepines were prescribed for longer than four months. It was concluded that benzodiazepines are often prescribed inappropriately, for a wide range of conditions and situations. Dr Mason (DHSS) and Dr Moir (SHHD) felt that, due to the large numbers of people using benzodiazepines for long periods of time, it was important to determine the effectiveness and toxicity of benzodiazepines before deciding what regulatory action to take.[92]Controversy resulted in 2010 when the previously secret files came to light over the fact that the Medical Research Council was warned that benzodiazepines prescribed to millions of patients appeared to cause brain shrinkage similar to alcohol abuse in some patients and failed to carry out larger and more rigorous studies. The Independent on Sunday reported allegations that "scores" of the 1.5 million members of the UK public who use benzodiazepines long-term have symptoms that are consistent with brain damage. It has been described as a "huge scandal" by Jim Dobbin, and legal experts and MPs have predicted a class action lawsuit. A solicitor said she was aware of the past failed litigation against the drug companies and the relevance the documents had to that court case and said it was strange that the documents were kept 'hidden' by the MRC.[99]

Professor Lader, who chaired the MRC meeting, declined to speculate as to why the MRC declined to support his request to set up a unit to further research benzodiazepines and why they did not set up a special safety committee to look into these concerns. Professor Lader stated that he regrets not being more proactive on pursuing the issue, stating that he did not want to be labeled as the guy who pushed only issues with benzos. Professor Ashton also submitted proposals for grant-funded research using MRI, EEG, and cognitive testing in a randomized controlled trial to assess whether benzodiazepines cause permanent damage to the brain, but similarly to Professor Lader was turned down by the MRC.[99]

The MRC spokesperson said they accept the conclusions of Professor Lader's research and said that they fund only research that meets required quality standards of scientific research, and stated that they were and continue to remain receptive to applications for research in this area. No explanation was reported for why the documents were sealed by the Public Records Act.[99]

Jim Dobbin, who chairs the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Involuntary Tranquilliser Addiction, stated that:

Many victims have lasting physical, cognitive and psychological problems even after they have withdrawn. We are seeking legal advice because we believe these documents are the bombshell they have been waiting for. The MRC must justify why there was no proper follow-up to Professor Lader's research, no safety committee, no study, nothing to further explore the results. We are talking about a huge scandal here.[99]The legal director of Action Against Medical Accidents said urgent research must be carried out and said that, if the results of larger studies confirm Professor Lader's research, the government and MRC could be faced with one of the biggest group actions for damages the courts have ever seen, given the large number of people potentially affected. People who report enduring symptoms post-withdrawal such as neurological pain, headaches, cognitive impairment, and memory loss have been left in the dark as to whether these symptoms are drug-induced damage or not due to the MRC's inaction, it was reported. Professor Lader reported that the results of his research did not surprise his research group given that it was already known that alcohol could cause permanent brain changes.[99]

Class-action lawsuit

Benzodiazepines have a unique history in that they were responsible for the largest-ever class-action lawsuit against drug manufacturers in the United Kingdom, in the 1980s and early 1990s, involving 14,000 patients and 1,800 law firms that alleged the manufacturers knew of the dependence potential but intentionally withheld this information from doctors. At the same time, 117 general practitioners and 50 health authorities were sued by patients to recover damages for the harmful effects of dependence and withdrawal. This led some doctors to require a signed consent form from their patients and to recommend that all patients be adequately warned of the risks of dependence and withdrawal before starting treatment with benzodiazepines.[100] The court case against the drug manufacturers never reached a verdict; legal aid had been withdrawn, leading to the collapse of the trial, and there were allegations that the consultant psychiatrists, the expert witnesses, had a conflict of interest. This litigation led to changes in the British law, making class-action lawsuits more difficult.[101]Special populations

Neonatal effects

Benzodiazepines have been found to cause teratogenic malformations.[102] The literature concerning the safety of benzodiazepines in pregnancy is unclear and controversial. Initial concerns regarding benzodiazepines in pregnancy began with alarming findings in animals but these do not necessarily cross over to humans. Conflicting findings have been found in babies exposed to benzodiazepines.[103] A recent analysis of the Swedish Medical Birth Register found an association with preterm births, low birth weight and a moderate increased risk for congental malformations. An increase in pylorostenosis or alimentary tract atresia was seen. An increase in orofacial clefts was not demonstrated, however, and it was concluded that benzodiazepines are not major teratogens.[104]Neurodevelopmental disorders and clinical symptoms are commonly found in babies exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. Benzodiazepine-exposed babies have a low birth weight but catch up to normal babies at an early age, but smaller head circumferences found in benzo babies persists. Other adverse effects of benzodiazepines taken during pregnancy are deviating neurodevelopmental and clinical symptoms including craniofacial anomalies, delayed development of pincer grasp, deviations in muscle tone and pattern of movements. Motor impairments in the babies are impeded for up to 1 year after birth. Gross motor development impairments take 18 months to return to normal but fine motor function impairments persist.[105] In addition to the smaller head circumference found in benzodiazepine-exposed babies mental retardation, functional deficits, long-lasting behavioural anomalies, and lower intelligence occurs.[106][107]

Benzodiazepines, like many other sedative hypnotic drugs, cause apoptotic neuronal cell death. However, benzodiazepines do not cause as severe apoptosis to the developing brain as alcohol does.[108][109][110] The prenatal toxicity of benzodiazepines is most likely due to their effects on neurotransmitter systems, cell membranes and protein synthesis.[111] This, however, is complicated in that neuropsychological or neuropsychiatric effects of benzodiazepines, if they occur, may not become apparent until later childhood or even adolescence.[112] A review of the literature found data on long-term follow-up regarding neurobehavioural outcomes is very limited.[113] However, a study was conducted that followed up 550 benzodiazepine-exposed children, which found that, overall, most children developed normally. There was a smaller subset of benzodiazepine-exposed children who were slower to develop, but by four years of age most of this subgroup of children had normalised. There was a small number of benzodiazepine-exposed children who had continuing developmental abnormalities at 4-year follow-up, but it was not possible to conclude whether these deficits were the result of benzodiazepines or whether social and environmental factors explained the continuing deficits.[114]

Concerns regarding whether benzodiazepines during pregnancy cause major malformations, in particular cleft palate, have been hotly debated in the literature. A meta analysis of the data from cohort studies found no link but meta analysis of case control studies did find a significant increase in major malformations. (However, the cohort studies were homogenous and the case control studies were heterogeneous, thus reducing the strength of the case control results). There have also been several reports that suggest that benzodiazepines have the potential to cause a syndrome similar to fetal alcohol syndrome, but this has been disputed by a number of studies. As a result of conflicting findings, use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy is controversial. The best available evidence suggests that benzodiazepines are not a major cause of birth defects, i.e. major malformations or cleft lip or cleft palate.[115]

Elderly

Significant toxicity from benzodiazepines can occur in the elderly as a result of long-term use.[116] Benzodiazepines, along with antihypertensives and drugs affecting the cholinergic system, are the most common cause of drug-induced dementia affecting over 10 percent of patients attending memory clinics.[117][118] Long-term use of benzodiazepines in the elderly can lead to a pharmacological syndrome with symptoms including drowsiness, ataxia, fatigue, confusion, weakness, dizziness, vertigo, syncope, reversible dementia, depression, impairment of intellect, psychomotor and sexual dysfunction, agitation, auditory and visual hallucinations, paranoid ideation, panic, delirium, depersonalisation, sleepwalking, aggressivity, orthostatic hypotension and insomnia. Depletion of certain neurotransmitters and cortisol levels and alterations in immune function and biological markers can also occur.[119] Elderly individuals who have been long-term users of benzodiazepines have been found to have a higher incidence of post-operative confusion.[120] Benzodiazepines have been associated with increased body sway in the elderly, which can potentially lead to fatal accidents including falls. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines leads to improvement in the balance of the body and also leads to improvements in cognitive functions in the elderly benzodiazepine hypnotic users without worsening of insomnia.[121]A review of the evidence has found that whilst long-term use of benzodiazepines impairs memory, its association with causing dementia is not clear and requires further research.[122] A more recent study found that benzodiazepines are associated with an increased risk of dementia and it is recommended that benzodiazepines be avoided in the elderly.[123] A later study, however, found no increase in dementia associated with long-term usage of benzodiazepine.[37]