From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An honor killing (American English), honour killing (Commonwealth English), or shame killing is the murder

of an individual, either an outsider or a member of a family, by

someone seeking to protect what they see as the dignity and honor of

themselves or their family. Honor killings are often connected to

religion, caste and other forms of hierarchical social stratification,

or to sexuality. Most often, it involves the murder of a woman or girl

by male family members, due to the perpetrators' belief that the victim

has brought dishonor or shame upon the family name, reputation or

prestige. Honor killings are believed to have originated from tribal customs. They are prevalent in various parts of the world, as well as in immigrant communities in countries which do not otherwise have societal norms that encourage honor killings. Honor killings are often associated with rural and tribal areas, but they occur in urban areas too.

Although condemned by international conventions and human rights

organizations, honor killings are often justified and encouraged by

various communities. In cases where the victim is an outsider, not

murdering this individual would, in some regions, cause family members

to be accused of cowardice,

a moral defect, and subsequently be morally stigmatized in their

community. In cases when the victim is a family member, the murdering

evolves from the perpetrators' perception that the victim has brought shame or dishonor upon the entire family, which could lead to social ostracization,

by violating the moral norms of a community. Typical reasons include

being in a relationship or having associations with social groups

outside the family that may lead to social exclusion of a family

(stigma-by-association). Examples are having premarital, extramarital or postmarital sex (in case of divorce or widowship), refusing to enter into an arranged marriage, seeking a divorce or separation, engaging in interfaith relations or relations with persons from a different caste, being the victim of a sexual crime, dressing in clothing, jewelry and accessories

that are associated with sexual deviance, engaging in a relationship in

spite of moral marriage impediments or bans, and homosexuality.

Though both men and women commit and are victims of honor

killings, in many communities conformity to moral standards implies

different behavior for men and women, including stricter standards for

chastity for women. In many families, the honor motive is used by men as

a pretext to restrict the rights of women.

Honor killings are primarily associated with countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), but are also rooted in other cultures, including India and the Philippines.

Definitions

Human Rights Watch defines "honor killings" as follows:

Honor crimes are acts of violence, usually murder,

committed by male family members against female family members who are

perceived to have brought dishonor upon the family. A woman can be

targeted by her family for a variety of reasons including, refusing to

enter into an arranged marriage, being the victim of a sexual assault,

seeking a divorce—even from an abusive husband—or committing adultery.

The mere perception that a woman has acted in a manner to bring

"dishonor" to the family is sufficient to trigger an attack.

Men can also be the victims of honor killings, either committed by

members of the family of a woman with whom they are perceived to have an

inappropriate relationship; or by the members of their own families,

the latter often connected to homosexuality.

General characteristics

Many

honor killings are planned by multiple members of a family, sometimes

through a formal "family council". The threat of murder is used as a

means to control behavior, especially concerning sexuality and marriage,

which may be seen as a duty for some or all family members to uphold.

Family members may feel compelled to act to preserve the reputation of

the family in the community and avoid stigma or shunning, particularly

in tight-knit communities. Perpetrators often do not face negative stigma within their communities, because their behavior is seen as justified.

Extent

Reliable

figures of honor killings are hard to obtain, in large part because

"honor" is either improperly defined or is defined in ways other than in

Article 12 of the UDHR

(block-quoted above) without a clear follow-up explanation. As a

result, criteria are hardly ever given for objectively determining

whether a given case is an instance of honor killing. Because of the

lack of both a clear definition of "honor" and coherent criteria, it is

often presupposed that more women than men are victims of honor

killings, and victim counts often contain women exclusively.

Honor killings occur in many parts of the world, but are most widely reported in the Middle East, South Asia and North Africa. Historically, honor killings were also common in Southern Europe, “there have been acts of ‘honour’ killings within living memory within Mediterranean countries such as Italy and Greece."

Methods

Methods of murdering include stoning, stabbing, beating, burning, beheading, hanging, throat slashing, lethal acid attacks, shooting, and strangulation.

Sometimes, communities perform murders in public to warn others in the

community of the possible consequences of engaging in what is seen as

illicit behavior.

Use of minors as perpetrators

Often,

minor girls and boys are selected by the family to act as the

murderers, so that the murderer may benefit from the most favorable

legal outcome. Boys and sometimes women in the family are often asked to

closely control and monitor the behavior of their sisters or other

females in the family, to ensure that the females do not do anything to

tarnish the 'honor' and 'reputation' of the family. The boys are often

asked to carry out the murder, and if they refuse, they may face serious

repercussions from the family and community for failing to perform

their "duty".

Culture

General cultural features

Further information:

NamusThe cultural features which lead to honor killings are complex. Honor

killings involve violence and fear as a tool for maintaining control.

Honor killings are argued to have their origins among nomadic peoples

and herdsmen: such populations carry all their valuables with them and

risk having them stolen, and they do not have proper recourse to law. As

a result, inspiring fear, using aggression, and cultivating a

reputation for violent revenge to protect property is preferable to

other behaviors. In societies where there is a weak rule of law, people

must build fierce reputations.

In many cultures where honor is of a central value, men are

sources, or active generators/agents, of that honor, while the only

effect that women can have on honor is to destroy it.

Once the family's or clan's honor is considered to have been destroyed

by a woman, there is a need for immediate revenge to restore it, for the

family to avoid losing face in the community. As Amnesty International statement notes:

The regime of honor is unforgiving:

women on whom suspicion has fallen are not allowed to defend

themselves, and family members have no socially acceptable alternative

but to remove the stain on their honor by attacking the woman.

The relation between social views on female sexuality

and honor killings are complex. The way through which women in

honor-based societies are considered to bring dishonor to men is often

through their sexual behavior. Indeed, violence related to female sexual

expression has been documented since Ancient Rome, when the pater familias

had the right to kill an unmarried sexually active daughter or an

adulterous wife. In medieval Europe, early Jewish law mandated stoning for an adulterous wife and her partner.

Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, an anthropology professor at Rhode Island College,

writes that an act, or even alleged act, of any female sexual

misconduct, upsets the moral order of the culture, and bloodshed is the

only way to remove any shame brought by the actions and restore social

equilibrium.

However, the relation between honor and female sexuality is a

complicated one, and some authors argue that it is not women's sexuality

per se that is the 'problem', but rather women's self-determination in regard to it, as well as fertility. Sharif Kanaana, professor of anthropology at Birzeit University, says that honor killing is:

A complicated issue that cuts deep

into the history of Islamic society. .. What the men of the family,

clan, or tribe seek control of in a patrilineal

society is reproductive power. Women for the tribe were considered a

factory for making men. Honor killing is not a means to control sexual

power or behavior. What's behind it is the issue of fertility or

reproductive power.

In some cultures, honor killings are considered less serious than

other murders simply because they arise from long-standing cultural

traditions and are thus deemed appropriate or justifiable.

Additionally, according to a poll done by the BBC's Asian network, 1 in

10 of the 500 young South Asians surveyed said they would condone any murder of someone who threatened their family's honor.

Nighat Taufeeq of the women's resource center Shirkatgah in Lahore,

Pakistan says: "It is an unholy alliance that works against women: the

killers take pride in what they have done, the tribal leaders condone

the act and protect the killers and the police connive the cover-up." The lawyer and human rights activist Hina Jilani says, "The right to life of women in Pakistan is conditional on their obeying social norms and traditions."

A July 2008 Turkish study by a team from Dicle University on honor killings in the Southeastern Anatolia Region,

the predominantly Kurdish area of Turkey, has so far shown that little

if any social stigma is attached to honor killing. It also comments that

the practice is not related to a feudal societal structure, "there are

also perpetrators who are well-educated university graduates. Of all

those surveyed, 60 percent are either high school or university

graduates or at the very least, literate."

In contemporary times, the changing cultural and economic status

of women has also been used to explain the occurrences of honor

killings. Women in largely patriarchal cultures who have gained economic

independence from their families go against their male-dominated

culture. Some researchers argue that the shift towards greater

responsibility for women and less for their fathers may cause their male

family members to act in oppressive and sometimes violent manners to

regain authority.

Fareena Alam,

editor of a Muslim magazine, writes that honor killings which arise in

Western cultures such as Britain are a tactic for immigrant families to

cope with the alienating consequences of urbanization. Alam argues that

immigrants remain close to the home culture and their relatives because

it provides a safety net. She writes that

In

villages "back home", a man's sphere of control was broader, with a

large support system. In our cities full of strangers, there is

virtually no control over who one's family members sit, talk or work

with.

Alam argues that it is thus the attempt to regain control and the

feelings of alienation that ultimately leads to an honor killing.

Specific triggers of honor killings

Refusal of an arranged or forced marriage

Refusal of an arranged marriage

or forced marriage is often a cause of an honor killing. The family

that has prearranged the marriage risks disgrace if the marriage does

not proceed, and the betrothed is indulged in a relationship with another individual without prior knowledge of the family members.

Seeking a divorce

A

woman attempting to obtain a divorce or separation without the consent

of the husband/extended family can also be a trigger for honor killings.

In cultures where marriages are arranged and goods are often exchanged

between families, a woman's desire to seek a divorce is often viewed as

an insult to the men who negotiated the deal. By making their marital problems known outside the family, the women are seen as exposing the family to public dishonor.

Allegations and rumors about a family member

In certain cultures, an allegation

against a woman can be enough to tarnish her family's reputation, and

to trigger an honor killing: the family's fear of being ostracized by

the community is enormous.

Victims of rape

In many cultures, victims of rape face severe violence, including

honor killings, from their families and relatives. In many parts of the

world, women who have been raped are considered to have brought

'dishonor' or 'disgrace' to their families. This is especially the case if the victim becomes pregnant.

Central to the code of honor, in many societies, is a woman's virginity, which must be preserved until marriage.

Suzanne Ruggi writes, "A woman's virginity is the property of the men

around her, first her father, later a gift for her husband; a virtual

dowry as she graduates to marriage."

Homosexuality

There is evidence that homosexuality

can also be perceived as grounds for honor killing by relatives. It is

not only same-sex sexual acts that trigger violence—behaviors that are

regarded as inappropriate gender expression (e.g. male acting or

dressing in a "feminine way") can also raise suspicion and lead to honor

violence.

In one case, a gay Jordanian man was shot and wounded by his brother. In another case, in 2008, a homosexual Turkish-Kurdish student, Ahmet Yildiz, was shot outside a cafe and later died in the hospital. Sociologists have called this Turkey's first publicized gay honor killing. In 2012, a 17-year-old gay youth was murdered by his father in Turkey in the southeastern province of Diyarbakır.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees states that "claims made by LGBT persons often reveal exposure to physical and sexual violence, extended periods of detention, medical abuse, the threat of execution and honor killing."

A 2019 study found that antigay "honor" abuse found more support

in four surveyed Asian countries (India, Iran, Malaysia, and Pakistan)

and among Asian British people than in a White British

sample. The study also found that women and younger people were less

likely to support such "honor" abuse. Muslims and Hindus were

substantially more likely to approve of "honor" abuse than Christians or

Buddhists, who scored lowest of the examined religious groups.

Forbidden male partners

In

many honor-based cultures, a woman maintains her honor through her

modesty. If a man disrupts a woman's modesty, through dating her, having

sex with her (especially if her virginity was lost), the man has

dishonored the woman, even if the relationship is consensual. Thus to

restore the woman's lost honor, the male members of her family will

often beat and murder the offender. Sometimes, violence extends to the

offender's family members, since honor feud attacks are seen as family

conflicts.

Interfaith and outside the caste relations

Some cultures have very strong caste social systems, based on social stratification characterized by endogamy,

hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an

occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, customary social interaction,

and exclusion based on cultural notions of purity and pollution. The caste system in India

is such an example. In such cultures, it is often expected that one

marries and forms closed associations only within one's caste, and

avoids lower castes. When these rules are violated, including relations

with people of a different religion, this can result in violence,

including honor killings.

Socializing outside the home

In some cultures, women are expected to have a primarily domestic role. Such ideas are often based on practices like purdah.

Purdah is a religious and social practice of female seclusion prevalent

among some Muslim and Hindu communities; it often requires having women

stay indoors, the avoiding of socialization between men and women, and

full body covering of women, including burqa.

When these rules are violated, including by dressing in a way deemed

inappropriate or displaying behavior seen as disobedient, the family may

respond with violence up to honor killings.

Renouncing or changing religion

Violating religious dogma, such as changing or renouncing religion can trigger honor killings.

Such ideas are supported by laws in some countries: blasphemy is

punishable by death in Afghanistan, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi

Arabia and Somalia; and punishable by prison in many other countries. Apostasy is also illegal in 25 countries, in some punishable with the death penalty.

Causes

There are multiple causes for which honor killings occur, and numerous factors interact with each other.

Views on women

Honor

killings are often a result of strongly misogynistic views towards

women and the position of women in society. In these traditionally

male-dominated societies, women are dependent first on their father and

then on their husbands, whom they are expected to obey. Women are viewed

as property and not as individuals with their own agency. As such, they

must submit to male authority figures in the family—failure to do so

can result in extreme violence as punishment. Violence is seen as a way of ensuring compliance and preventing rebellion.

According to Shahid Khan, a professor at the Aga Khan University in

Pakistan: "Women are considered the property of the males in their

family irrespective of their class, ethnic, or religious group. The

owner of the property has the right to decide its fate. The concept of

ownership has turned women into a commodity which can be exchanged,

bought and sold".

In such cultures, women are not allowed to take control over their

bodies and sexuality: these are the property of the males of the family,

the father (and other male relatives) who must ensure virginity until

marriage; and then the husband to whom his wife's sexuality is

subordinated—a woman must not undermine the ownership rights of her

guardian by engaging in premarital sex or adultery.

Cultures of honor and shame

The concept of family honor

is extremely important in many communities worldwide. The UN estimates

that 5,000 women and girls are murdered each year in honor killings,

which are widely reported in the Middle East and South Asia, but they

occur in countries as varied as Brazil, Canada, Iran, Israel, Italy,

Jordan, Egypt, Sweden, Syria, Uganda, United Kingdom, the United States,

and other countries. In honor cultures, managing reputation is an important social ethic.

Men are expected to act tough and be intolerant of disrespect and women

are expected to be loyal to the family and be chaste.

An insult to your personal or family honor must be met with a response,

or the stain of dishonor can affect many others in the family and the

wider community. Such acts often include female behaviors that are

related to sex outside marriage or way of dressing, but may also include male homosexuality (like the emo killings in Iraq).

The family may lose respect in the community and may be shunned by

relatives. The only way they perceive that shame can be erased is

through an honor killing. The cultures in which honor killings take place are usually considered "collectivist cultures",

where the family is more important than the individual, and individual

autonomy is seen as a threat to the family and its honor.

Though it may seem in a modern context that honor killings are

tied to certain religious traditions, the data does not support this

claim.

Research in Jordan found that teenagers who strongly endorsed honor

killings in fact did not come from more religious households than teens

who rejected it.

The ideology of honor is a cultural phenomenon that does not appear to

be related to religion, be it Middle Eastern or Western countries, and

honor killings likely have a long history in human societies which

predate many modern religions.

In the US, a rural trend known as the "small-town effect" exhibit

elevated incidents of argument-related homicides among white males,

particularly in honor-oriented states in the South and the West, where

everyone "knows your name and knows your shame." This is similarly

observed in rural areas in other parts of the world.

Honor cultures pervade in places of economic vulnerability and

with the absence of the rule of law, where law enforcement cannot be

counted on to protect them.

People then resort to their reputations to protect them from social

exploitation and a man must "stand up for himself" and not rely on

others to do so.

To lose your honor is to lose this protective barrier. Possessing honor

in such a society can grant social status and economic and social

opportunities. When honor is ruined, a person or family in an honor

culture can be socially ostracized, face restricted economic

opportunities, and have a difficult time finding a mate.

Laws and European colonialism

Legal frameworks can encourage honor killings. Such laws include on

one side leniency towards such murdering, and on the other side

criminalization of various behaviors, such as extramarital sex,

"indecent" dressing in public places, or homosexual sexual acts, with

these laws acting as a way of reassuring perpetrators of honor killings

that people engaging in these behaviors deserve punishment.

In the Roman Empire the Roman law Lex Julia de adulteriis coercendis implemented by Augustus

Caesar permitted the murder of daughters and their lovers who committed

adultery at the hands of their fathers and also permitted the murder of

the adulterous wife's lover at the hand of her husband.

Provocation in English law and related laws on adultery in English law,

as well as Article 324 of the French penal code of 1810 were legal

concepts which allowed for reduced punishment for the murder committed

by a husband against his wife and her lover if the husband had caught

them in the act of adultery.

On 7 November 1975, Law no. 617/75 Article 17 repealed the 1810 French

Penal Code Article 324. The 1810 penal code Article 324 passed by

Napoleon was copied by Middle Eastern Arab countries. It inspired Jordan's

Article 340 which permitted the murder of a wife and her lover if

caught in the act at the hands of her husband (today the article

provides for mitigating circumstances).

France's 1810 Penal Code Article 324 also inspired the 1858 Ottoman

Penal Code's Article 188, both the French Article 324 and Ottoman

article 188 were drawn on to create Jordan's Article 340 which was

retained even after a 1944 revision of Jordan's laws which did not touch

public conduct and family law; article 340 still applies to this day in a modified form.

France's Mandate over Lebanon resulted in its penal code being imposed

there in 1943–1944, with the French-inspired Lebanese law for adultery

allowing the mere accusation of adultery against women resulting in a

maximum punishment of two years in prison while men have to be caught in

the act and not merely accused, and are punished with only one year in

prison.

France's Article 324 inspired laws in other Arab countries such as:

- Algeria's 1991 Penal Code Article 279

- Egypt's 1937 Penal Code no. 58 Article 237

- Iraq's 1966 Penal Code Article 409

- Jordan's 1960 Penal Code no. 16 Article 340

- Kuwait's Penal Code Article 153

- Lebanon's Penal Code Articles 193, 252, 253 and 562

- These were amended in 1983, 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1999 and were eventually repealed by the Lebanese Parliament on 4 August 2011

- Libya's Penal Code Article 375

- Morocco's 1963 amended Penal Code Article 418

- Oman's Penal Code Article 252

- Palestine, which had two codes: Jordan's 1960 Penal Code 1960 in the

West Bank and British Mandate Criminal Code Article 18 in the Gaza

Strip

- These were respectively repealed by Article 1 and Article 2 and

both by Article 3 of the 2011 Law no. 71 which was signed on 5 May 2011

by president Mahmoud Abbas into the 10 October 2011 Official Gazette no.

91 applying in the Criminal Code of Palestine's Northern Governorates

and Southern Governorates

- Syria's 1953 amended 1949 Penal Code Article 548

- Tunisia's 1991 Penal Code Article 207 (which was repealed)

- United Arab Emirate's law no.3/1978 Article 334

- Yemen's law no. 12/1994 Article 232

In Pakistan, the law was based upon on the 1860 Indian Penal Code (IPC) implemented by the colonial authorities in British India,

which allowed for mitigation of punishment for charges of assault or

criminal force in the case of a "grave and sudden provocation". This

clause was used to justify the legal status of honor killing in

Pakistan, although the IPC makes no mention of it. In 1990, the Pakistani government reformed this law to bring it in terms with the Shari'a,

and the Pakistani Federal Shariat Court declared that "according to the

teachings of Islam, provocation, no matter how grave and sudden it is,

does not lessen the intensity of crime of murder". However, Pakistani

judges still sometimes hand down lenient sentences for honor killings,

justified by still citing the IPC's mention of a "grave and sudden

provocation."

Forced suicide as a substitute

A forced suicide may be a substitute for an honor killing. In this

case, the family members do not directly murder the victim themselves,

but force him or her to commit suicide, in order to avoid punishment.

Such suicides are reported to be common in southeastern Turkey. It was reported that in 2001, 565 women lost their lives in honor-related crimes in Ilam, Iran, of which 375 were reportedly staged as self-immolation.

In 2008, self-immolation "occurred in all the areas of Kurdish

settlement (in Iran), where it was more common than in other parts of

Iran". It is claimed that in Iraqi Kurdistan many deaths are reported as "female suicides" in order to conceal honor-related crimes.

Restoring honor through a forced marriage

In the case of an unmarried woman or girl associating herself with a

man, losing virginity, or being raped, the family may attempt to restore

its 'honor' with a 'shotgun wedding'. The groom will usually be the man

who has 'dishonored' the woman or girl, but if this is not possible the

family may try to arrange a marriage with another man, often a man who

is part of the extended family of the one who has committed the acts

with the woman or girl. This being an alternative to an honor killing,

the woman or girl has no choice but to accept the marriage. The family

of the man is expected to cooperate and provide a groom for the woman.

Religion

Widney Brown, the advocacy director of Human Rights Watch, said that the practice "goes across cultures and religions".

Resolution 1327 (2003) of the Council of Europe states that:

The Assembly notes that whilst

so-called "honor crimes" emanate from cultural and not religious roots

and are perpetrated worldwide (mainly in patriarchal societies or

communities), the majority of reported cases in Europe have been among Muslim or migrant Muslim communities (although Islam itself does not support the death penalty for honor-related misconduct).

Many Muslim commentators and organizations condemn honor killings as an un-Islamic cultural practice. There is no mention of honor killing (extrajudicial killing by a woman's family) in the Qur'an, and the practice violates Islamic law. Tahira Shaid Khan, a professor of women's issues at Aga Khan University,

blames such murdering on attitudes (across different classes, ethnic,

and religious groups) that view women as property with no rights of

their own as the motivation for honor killings. Ali Gomaa, Egypt's former Grand Mufti, has also spoken out forcefully against honor killings.

As a more generic statement reflecting the wider Islamic scholarly trend, Jonathan A. C. Brown says that "questions about honor killings have regularly found their way into the inboxes of muftis like Yusuf Qaradawi or the late scholar Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah. Their responses reflect a rare consensus.

No Muslim scholar of any note, either medieval or modern, has

sanctioned a man killing his wife or sister for tarnishing her or the

family's honor. If a woman or man found together were to deserve the

death penalty for fornication, this would have to be established by the

evidence required by the Koran: either a confession or the testimony of

four male witnesses, all upstanding in the eyes of the court, who

actually saw penetration occur."

Further, while honor killings are common in Muslim countries like Pakistan and the Arab nation, it is a practically unknown practice in other Muslim countries, such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Senegal. This fact supports the idea that honor killings are to do with culture rather than religion.

The late Yemeni Muslim scholar Muḥammad Shawkānī wrote that one reason the Shari'a

stipulates execution as a potential punishment for men who murder women

is to counter honor killings for alleged slights of honor. He wrote,

"There is no doubt that laxity on this matter is one of the greatest

means leading to women's lives being destroyed, especially in the

Bedouin regions, which are characterized by harsh-hardheartedness and a

strong sense of honor and shame stemming from Pre-Islamic times".

In history

Matthew A. Goldstein, J.D. (Arizona), has noted that honor killings were encouraged in ancient Rome, where male family members who did not take action against the female adulterers in their families were "actively persecuted".

The origin of honor killings and the control of women is

evidenced throughout history in the cultures and traditions of many

regions. The Roman law of pater familias

gave complete control to the men of the family over both their children

and wives. Under these laws, the lives of children and wives were at

the discretion of the men in their families. Ancient Roman Law also

justified honor killings by stating that women who were found guilty of

adultery could be killed by their husbands. During the Qing dynasty in China, fathers and husbands had the right to kill daughters who were deemed to have dishonored the family.

Among the Indigenous Aztecs and Incas, adultery was punishable by death. During John Calvin's rule of Geneva, women found guilty of adultery were punished by being drowned in the Rhône river.

Honor killings have a long tradition in Mediterranean Europe. According to the Honour Related Violence – European Resource Book and Good Practice

(page 234): "Honor in the Mediterranean world is a code of conduct, a

way of life and an ideal of the social order, which defines the lives,

the customs and the values of many of the peoples in the Mediterranean

moral".

By region

According to the UN in 2002:

The report of the Special Rapporteur...

concerning cultural practices in the family that are violent towards

women (E/CN.4/2002/83), indicated that honor killings had been reported

in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon (the Lebanese Parliament abolished the Honor killing in August 2011), Morocco, Pakistan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, Yemen, and other Mediterranean and Persian Gulf countries, and that they had also taken place in western countries such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom, within migrant communities.

In addition, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights gathered

reports from several countries and considering only the countries that

submitted reports it was shown that honor killings have occurred in Bangladesh, Great Britain, Brazil, Ecuador, Egypt, India, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Pakistan, Morocco, Sweden, Turkey, and Uganda.

According to Widney Brown, advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, the practice of honor killing "goes across cultures and religions."

International response

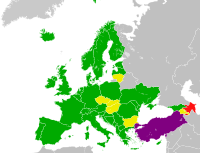

The

Istanbul Convention,

the first legally binding international instrument on violence against

women, prohibits honor killings. Countries listed in green on the map

are members to this convention, and, as such, have the obligation to

outlaw honor killings.

Honor killings are condemned as a serious human rights violation and are addressed by several international instruments.

Honor killings are opposed by United Nations General Assembly

Resolution 55/66 (adopted in 2000) and subsequent resolutions, which

have generated various reports.

The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence addresses this issue. Article 42 reads:

Article 42 – Unacceptable justifications for crimes, including crimes committed in the name of so-called honor

1. Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures

to ensure that, in criminal proceedings initiated following the

commission of any of the acts of violence covered by the scope of this

Convention, culture, custom, religion, tradition, or so-called honor

shall not be regarded as justification for such acts. This covers, in

particular, claims that the victim has transgressed cultural, religious,

social, or traditional norms or customs of appropriate behavior.

2. Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures

to ensure that incitement by any person of a child to commit any of the

acts referred to in paragraph 1 shall not diminish the criminal

liability of that person for the acts committed.

The World Health Organization

(WHO) addressed the issue of honor killings and stated: "Murders of

women to 'save the family honor' are among the most tragic consequences

and explicit illustrations of embedded, culturally accepted

discrimination against women and girls." According to the UNODC:

"Honour crimes, including killing, are one of history's oldest forms of

gender-based violence. It assumes that a woman's behavior casts a

reflection on the family and the community. ... In some communities, a

father, brother, or cousin will publicly take pride in a murder

committed to preserving the 'honor' of a family. In some such cases,

local justice officials may side with the family and take no formal

action to prevent similar deaths."

In national legal codes

Legislation

on this issue varies, but today the vast majority of countries no

longer allow a husband to legally murder a wife for adultery (although adultery itself continues to be punishable by death

in some countries) or to commit other forms of honor killings. However,

in many places, adultery and other "immoral" sexual behaviors by female

family members can be considered mitigating circumstances in the case when they are murdered, leading to significantly shorter sentences.

Contemporary laws which allow for mitigating circumstances or

acquittals for men who murder female family members due to sexual

behaviors are, for the most part, inspired by the French Napoleonic Code

(France's crime of passion law, which remained in force until 1975).

The Middle East, including the Arab countries of North Africa, Iran and

non-Arab minorities within Arabic countries, have high recorded level

of honor crimes, and these regions are the most likely to have laws

offering complete or partial defenses to honor killings. However, with

the exception of Iran, laws which provide leniency for honor killings

are not derived from Islamic law, but from the penal codes of the

Napoleonic Empire. French culture

shows a higher level of toleration of such crimes among the public,

compared to other Western countries; and indeed, recent surveys have

shown the French public to be more accepting of these practices than the

public in other countries. One 2008 Gallup survey compared the views of

the French, German and British public and those of French, German and

British Muslims on several social issues: 4% of the French public said

"honor killings" were "morally acceptable" and 8% of the French public

said "crimes of passion" were "morally acceptable"; honor killings were

seen as acceptable by 1% of German public and also 1% of the British

public; crimes of passion were seen as acceptable by 1% of German public

and 2% of the British public. Among Muslims, 5% in Paris, 3% in Berlin,

and 3% in London saw honor killings as acceptable, and 4% in Paris

(less than the French public), 1% in Berlin, and 3% in London saw crimes

of passion as acceptable.

According to the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur submitted to the 58th session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in 2002 concerning cultural practices in the family that reflect violence against women (E/CN.4/2002/83):

The Special Rapporteur indicated that there had been contradictory decisions with regard to the honor defense in Brazil, and that legislative provisions allowing for partial or complete defence in that context could be found in the penal codes of Argentina, Ecuador, Egypt, Guatemala, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Peru, Syria, Venezuela and the Palestinian National Authority.

As of 2022, most countries with complete or partial defenses for killings due to sexual behaviors or parental disobedience are MENA countries, but there are some notable exceptions, namely Philippines. The legal aspects of honor killings in different countries are discussed below:

- Yemen: laws effectively exonerate fathers who murder their children; also the blood money paid for females that are murdered is less than that for males that are murdered.

- Iran:

Article 630 exempts a husband from punishment if he murders his wife or

her lover upon discovering them in the act of adultery; article 301

stipulates that a father and paternal grandfather are not to be

retaliated against for murdering their child/grandchild.

- Jordan: In recent years, Jordan has amended its Code to modify its laws which used to offer a complete defense for honor killings.

- Syria:

In 2009, Article 548 of the Syrian Law code was amended. Beforehand,

the article waived any punishment for males who murdered a female family

member for inappropriate sexual acts. Article 548 states that "He who catches his wife or one of his ascendants, descendants or sister committing adultery (flagrante delicto)

or illegitimate sexual acts with another and he killed or injured one

or both of them benefits from a reduced penalty, that should not be less

than two years in prison in case of killing." Article 192 states that a

judge may opt for reduced punishments (such as short-term imprisonment)

if the murder was done with an honorable intent. In addition to this,

Article 242 says that a judge may reduce a sentence for murders that

were done in rage and caused by an illegal act committed by the victim.

- In Brazil,

an explicit defense to murder in case of adultery has never been part

of the criminal code, but a defense of "honor" (not part of the criminal

code) has been widely used by lawyers in such cases to obtain

acquittals. Although this defense has been generally rejected in modern

parts of the country (such as big cities) since the 1950s, it has been

very successful in the interior of the country. In 1991 Brazil's Supreme

Court explicitly rejected the "honor" defense as having no basis in

Brazilian law.

- Turkey: In Turkey, persons found guilty of this crime are sentenced to life in prison.

There are well documented cases, where Turkish courts have sentenced

whole families to life imprisonment for an honor killing. The most

recent was on 13 January 2009, where a Turkish Court sentenced five

members of the same Kurdish family to life imprisonment for the honor

killing of Naile Erdas, 16, who got pregnant as a result of rape.

- Pakistan: Honor killings are known as karo kari (Sindhi: ڪارو ڪاري) (Urdu: کاروکاری). The practice is supposed to be prosecuted under the ordinary killing, but in practice police and prosecutors often ignore it. Often a man must simply claim the murdering was for his honor and he will go free. Nilofar Bakhtiar, advisor to Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz, stated that in 2003, as many as 1,261 women were murdered in honor killings.

The Hudood Ordinances of Pakistan, enacted in 1979 by then ruler

General Zia-ul-Haq. The law had the effect of reducing the legal

protections for women, especially regarding sex outside of the marriage.

This law made it that much riskier for women to come forward with

accusations of rape. In 2006, the Women's Protection Bill amended these

Hudood Ordinances.

On 8 December 2004, under international and domestic pressure, Pakistan

enacted a new law that made honor killings punishable by a prison term

of seven years, or by the death penalty in the most extreme cases.

In 2016, Pakistan repealed the loophole which allowed the perpetrators

of honor killings to avoid punishment by seeking forgiveness for the

crime from another family member, and thus be legally pardoned.

- Egypt: Several studies on honor crimes by The Centre of Islamic and Middle Eastern Law, at the School of Oriental and African Studies

in London, includes one which reports on Egypt's legal system, noting a

gender bias in favor of men in general, and notably article 17 of the

Penal Code: judicial discretion to allow reduced punishment in certain

circumstance, often used in honor killings case.

- Haiti:

In 2005, the laws were changed, abolishing the right of a husband to be

excused for murdering his wife due to adultery. Adultery was also

decriminalized.

- Uruguay: until December 2017, article 36 of the Penal Code provided for the exoneration for murder of a spouse due to "the passion provoked by adultery". The case of violence against women in Uruguay has been debated in the context that it is otherwise a liberal country;

nevertheless domestic violence is a very serious problem; according to a

2018 United Nations study, Uruguay has the second-highest rate of

killings of women by current or former partners in Latin America, after

Dominican Republic.

Despite having a reputation of being a progressive country, Uruguay has

lagged behind with regard to its approach to domestic violence; for example, in Chile,

considered one of the most socially conservative countries of the

region, similar legislation permitting such honor killings was repealed

in 1953.

- Philippines:

murdering one's spouse upon being caught in the act of adultery or

one's daughter upon being caught in the act of premarital sex is

punished by destierro (Art. 247)(destierro

is banishment from a geographical area for a period of time).

Philippine maintains several other traditionalist laws: it is the only

country in the world (except Vatican City) that bans divorce; it is one

of 20 countries that still has a marry-your-rapist law (that is, a law that exonerates a rapist from punishment if he marries the victim after the attack); and Philippine is also one of the few non-Muslim majority countries to have a criminal law against adultery

(Philippine's adultery law also differentiates by gender defining and

punishing adultery more severely if committed by women - see articles

Articles 333 and 334)

Support and sanction

Actions of Pakistani police officers and judges (particularly at the lower level of the judiciary)

have, in the past, seemed to support the act of honor killings in the

name of family honor. Police enforcement, in situations of admitted

murder, does not always take action against the perpetrator. Also,

judges in Pakistan (particularly at the lower level of the judiciary),

rather than ruling cases with gender equality in mind, also seem to

reinforce inequality and in some cases sanction the murder of women

considered dishonorable.

Often, a suspected honor killing never even reaches court, but in cases

where they do, the alleged killer is often not charged or is given a

reduced sentence of three to four years in jail. In a case study of 150

honor killings, the proceeding judges rejected only eight claims that

the women were murdered for the honor. The rest were sentenced lightly.

In many cases in Pakistan, one of the reasons honor killing cases never

make it to the courts, is because, according to some lawyers and

women's right activists, Pakistani law enforcement do not get involved.

Under the encouragement of the killer, police often declare the killing

as a domestic case that warrants no involvement. In other cases, the

women and victims are too afraid to speak up or press charges. Police

officials, however, claim that these cases are never brought to them, or

are not major enough to be pursued on a large scale. The general indifference to the issue of honor killing within Pakistan is due to a deep-rooted gender bias in law, the police force, and the judiciary. In its report, "Pakistan: Honor Killings of Girls and Women",

published in September 1999, Amnesty International criticized

governmental indifference and called for state responsibility in

protecting human rights of female victims. To elaborate, Amnesty

strongly requested the Government of Pakistan to take 1) legal, 2)

preventive, and 3) protective measures. First of all, legal measures

refer to a modification of the government's criminal laws to guarantee

equal legal protection of females. On top of that, Amnesty insisted the

government assure legal access for the victims of crime in the name of

honor. When it comes to preventive measures, Amnesty underlined the

critical need to promote public awareness through the means of media,

education, and public announcements. Finally, protective measures

include ensuring a safe environment for activists, lawyers, and women's

groups to facilitate the eradication of honor killings. Also, Amnesty

argued for the expansion of victim support services such as shelters.

Kremlin-appointed Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov

said that honor killings were perpetrated on those who deserved to die.

He said that those who are killed have "loose morals" and are

rightfully shot by relatives in honor killings. He did not vilify women

alone but added that "If a woman runs around and if a man runs around

with her, both of them are killed."

In 2007, a famous Norwegian Supreme Court advocate stated that he

wanted the punishment for the killing reduced from 17 years in prison

to 15 years in the case of honor killings practiced in Norway.

He explained that the Norwegian public did not understand other

cultures who practiced honor killings, or understand their thinking, and

that Norwegian culture "is self-righteous".

In 2008, Israr Ullah Zehri, a Pakistani politician in Balochistan, defended the honor killings of five women belonging to the Umrani tribe by a relative of a local Umrani politician.

Zehri defended the murdering in Parliament and asked his fellow

legislators not to make a fuss about the incident. He said, "These are

centuries-old traditions, and I will continue to defend them. Only those

who indulge in immoral acts should be afraid."

Nilofar Bakhtiar,

who's the Minister for Tourism and Advisor to Pakistan Prime Minister

on Women's Affairs, had struggled against the honor killing in Pakistan,

resigned in April 2007 after the clerics accused her of bringing shame

to Pakistan by para-jumping with a male and hugging him after landing.

Victims

This is an incomplete list of notable victims of Honor killing. See also Category:Victims of honor killing

- Rania Alayed (UK)

- Noor Faleh Almaleki

- Shafilea Ahmed – Murdered by the family for rejecting a marriage partner.

- Du'a Khalil Aswad – Yazidi girl who was killed for supposedly converting to Islam to date a Muslim boy in Iraq

- Surjit Athwal (Murder planned in the UK and carried out in India)

- Gelareh Bagherzadeh (US) - For encouraging her friend Nesreen Irsan to leave Islam (US)

- Qandeel Baloch

- Coty Beavers - for marrying Nesreen Irsan (US)

- Anooshe Sediq Ghulam

- Tulay Goren (UK)

- Leila Hussein and her daughter Rand Abdel-Qader

- Palestina Isa

- Manoj and Babli

- Sandeela Kanwal

- Nitish Katara

- Ghazala Khan – Murdered by her brother for marrying against the will of the family.

- Katya Koren (Ukraine)

- Banaz Mahmod. Her story was chronicled in the 2012 documentary film Banaz a Love Story.

- Rukhsana Naz (UK)

- Samaira Nazir

- Morsal Obeidi (Germany)

- Aqsa Parvez

- Uzma Rahan and her children: sons, Adam and Abbas, and daughter, Henna (UK)

- Caneze Riaz and her four daughters, Sayrah, Sophia, Alicia and Hannah (UK)

- Fadime Sahindal

- Tursunoy Saidazimova

- Amina and Sarah Said

- Hina Salem (Italy)

- Samia Sarwar

- Zainab, Sahar, and Geeti Shafia, and Rona Amir Mohammad

- Sadia Sheikh

- Jaswinder Kaur Sidhu

- Hatun Sürücü

- Swera (Switzerland)

- Heshu Yones (UK)

- Nurkhon Yuldasheva

- Aasiya Zubair

- Shafia family murders

took place on June 30, 2009, in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Shafia

sisters Zainab, 19, Sahar, 17, and Geeti, 13, along with Rona Muhammad

Omar, 52 (all of Afghan origin), were found dead inside a car.

Comparison to other forms of murdering

Honor killings are, along with dowry killings (most of which are committed in South Asia),

gang-related murderings of women as revenge (killings of female members

of rival gang members' families—most of which are committed in Latin America) and witchcraft accusation killings (most of which are committed in Africa and Oceania) are some of the most recognized forms of femicide.

Human rights advocates have compared "honor killings" to "crimes of passion" in Latin America (which are sometimes treated extremely leniently) and the murdering of women for lack of dowry in India.

Some commentators have stressed the point that the focus on honor

killings should not lead people to ignore other forms of gender-based

murdering of women, in particular, those which occur in Latin America

("crimes of passion" and gang-related killings); the murder rate of

women in this region is extremely high, with El Salvador being reported as the country with the highest rate of murders of women in the world. In 2002, Widney Brown, advocacy director for Human Rights Watch,

stated that "crimes of passion have a similar dynamic in that the women

are murdered by male family members and the crimes are perceived as

excusable or understandable".