From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

|---|

| Other names | Chronic

obstructive lung disease (COLD), chronic obstructive airway disease

(COAD), chronic bronchitis, emphysema, pulmonary emphysema, others |

|---|

|

| Gross pathology of a lung showing centrilobular emphysema characteristic of smoking. This close-up of the fixed, cut lung surface shows multiple cavities filled with heavy black carbon deposits. |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

|---|

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, cough with sputum production. |

|---|

| Complications | Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

|---|

| Usual onset | Over 40 years old |

|---|

| Duration | Long term |

|---|

| Causes | Tobacco smoking, air pollution, genetics |

|---|

| Diagnostic method | Lung function tests |

|---|

| Differential diagnosis | Asthma, Asbestosis, Bronchiectasis, Tracheobronchomalacia |

|---|

| Prevention | Improving indoor and outdoor air quality, tobacco control measures |

|---|

| Treatment | Stopping smoking, respiratory rehabilitation, lung transplantation |

|---|

| Medication | Vaccinations, inhaled bronchodilators and steroids, long-term oxygen therapy |

|---|

| Frequency | 174.5 million (2015) |

|---|

| Deaths | 3.2 million (2015) |

|---|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a type of obstructive lung disease characterized by long-term breathing problems and poor airflow. The main symptoms include shortness of breath and cough with sputum production. COPD is a progressive disease, meaning it typically worsens over time. Eventually, everyday activities such as walking or getting dressed become difficult. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are older terms used for different types of COPD.

The term "chronic bronchitis" is still used to define a productive

cough that is present for at least three months each year for two years. Those with such a cough are at a greater risk of developing COPD. The term "emphysema" is also used for the abnormal presence of air or other gas within tissues.

The most common cause of COPD is tobacco smoking, with a smaller number of cases due to factors such as air pollution and genetics. In the developing world, one of the common sources of air pollution is poorly vented heating and cooking fires. Long-term exposure to these irritants causes an inflammatory response in the lungs, resulting in narrowing of the small airways and breakdown of lung tissue. The diagnosis is based on poor airflow as measured by lung function tests. In contrast to asthma, the airflow reduction does not improve much with the use of a bronchodilator.

Most cases of COPD can be prevented by reducing exposure to risk factors. This includes decreasing rates of smoking and improving indoor and outdoor air quality. While treatment can slow worsening, no cure is known. COPD treatments include smoking cessation, vaccinations, respiratory rehabilitation, and often inhaled bronchodilators and steroids. Some people may benefit from long-term oxygen therapy or lung transplantation. In those who have periods of acute worsening, increased use of medications, antibiotics, steroids, and hospitalization may be needed.

As of 2015, COPD affected about 174.5 million people (2.4% of the global population). It typically occurs in people over the age of 40. Males and females are affected equally commonly. In 2015, it caused 3.2 million deaths, more than 90% in the developing world, up from 2.4 million deaths in 1990.

The number of deaths is projected to increase further because of higher

smoking rates in the developing world, and an ageing population in many

countries. It resulted in an estimated economic cost of US$2.1 trillion in 2010.

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptoms of COPD are shortness of breath, and a cough that produces sputum. These symptoms are present for a prolonged period of time and typically worsen over time. It is unclear whether different types of COPD exist.

While previously divided into emphysema and chronic bronchitis,

emphysema is only a description of lung changes rather than a disease

itself, and chronic bronchitis is simply a descriptor of symptoms that

may or may not occur with COPD.

Cough

A chronic cough is often the first symptom to develop. Early on it may just occur occasionally or may not result in sputum. When a cough persists for more than three months each year for at least two years, in combination with sputum production and without another explanation, it is by definition chronic bronchitis. Chronic bronchitis can occur before the restricted airflow and thus COPD fully develops.

The amount of sputum produced can change over hours to days. In some cases, the cough may not be present or may only occur occasionally and may not be productive. Some people with COPD attribute the symptoms to a "smoker's cough". Sputum may be swallowed or spat out, depending often on social and cultural factors. In severe COPD, vigorous coughing may lead to rib fractures or to a brief loss of consciousness. Those with COPD often have a history of "common colds" that last a long time.

Shortness of breath

Shortness of breath is a common symptom and is often the most distressing. It is commonly described as: "my breathing requires effort," "I feel out of breath," or "I can't get enough air in." Different terms, however, may be used in different cultures. Typically, the shortness of breath is worse on exertion of a prolonged duration and worsens over time. In the advanced stages, or end stage pulmonary disease, it occurs during rest and may be always present. Shortness of breath is a source of both anxiety and a poor quality of life in those with COPD. Many people with more advanced COPD breathe through pursed lips and this action can improve shortness of breath in some.

Physical activity limitation

COPD often leads to reduction in physical activity, in part due to shortness of breath. In later stages of COPD muscle wasting (cachexia) may occur. Low levels of physical activity are associated with worse outcomes.

Other symptoms

In COPD, breathing out may take longer than breathing in. Chest tightness may occur, but is not common and may be caused by another problem. Those with obstructed airflow may have wheezing or decreased sounds with air entry on examination of the chest with a stethoscope. A barrel chest is a characteristic sign of COPD, but is relatively uncommon. Tripod positioning may occur as the disease worsens.

Advanced COPD leads to high pressure on the lung arteries, which strains the right ventricle of the heart. This situation is referred to as cor pulmonale, and leads to symptoms of leg swelling and bulging neck veins. COPD is more common than any other lung disease as a cause of cor pulmonale. Cor pulmonale has become less common since the use of supplemental oxygen.

COPD often occurs along with a number of other conditions, due in part to shared risk factors. These conditions include ischemic heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, muscle wasting, osteoporosis, lung cancer, anxiety disorder, sexual dysfunction, and depression. In those with severe disease, a feeling of always being tired is common. Fingernail clubbing is not specific to COPD and should prompt investigations for an underlying lung cancer.

Exacerbation

An acute exacerbation of COPD

is defined as increased shortness of breath, increased sputum

production, a change in the color of the sputum from clear to green or

yellow, or an increase in cough in someone with COPD. They may present with signs of increased work of breathing such as fast breathing, a fast heart rate, sweating, active use of muscles in the neck, a bluish tinge to the skin, and confusion or combative behavior in very severe exacerbations. Crackles may also be heard over the lungs on examination with a stethoscope.

Cause

The primary

cause of COPD is tobacco smoke, with occupational exposure and

pollution from indoor fires being significant causes in some countries. Typically, these must occur over several decades before symptoms develop. A person's genetic makeup also affects the risk.

Smoking

Percentage of females smoking tobacco as of the late 1990s early 2000s

Percentage of males smoking tobacco as of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Note the scales used for females and males differ.

The primary risk factor for COPD globally is tobacco smoking. Of those who smoke, about 20% will get COPD, and of those who are lifelong smokers, about half will get COPD. In the United States and United Kingdom, of those with COPD, 80–95% are either current or previous smokers. The likelihood of developing COPD increases with the total smoke exposure. Additionally, women are more susceptible to the harmful effects of smoke than men. In non-smokers, exposure to second-hand smoke is the cause in up to 20% of cases. Other types of smoke, such as, marijuana, cigar, and water-pipe smoke, also confer a risk. Water-pipe smoke appears to be as harmful as smoking cigarettes. Problems from marijuana smoke may only be with heavy use. Women who smoke during pregnancy may increase the risk of COPD in their child. For the same amount of cigarette smoking, women have a higher risk of COPD than men.

Air pollution

Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking as of 2016

Poorly ventilated cooking fires, often fueled by coal or biomass fuels such as wood and dung, lead to indoor air pollution and are one of the most common causes of COPD in developing countries.

These fires are a method of cooking and heating for nearly 3 billion

people, with their health effects being greater among women due to

greater exposure. They are used as the main source of energy in 80% of homes in India, China and sub-Saharan Africa.

People who live in large cities have a higher rate of COPD compared to people who live in rural areas. While urban air pollution is a contributing factor in exacerbations, its overall role as a cause of COPD is unclear. Areas with poor outdoor air quality, including that from exhaust gas, generally have higher rates of COPD. The overall effect in relation to smoking, however, is believed to be small.

Occupational exposure

Intense

and prolonged exposure to workplace dusts, chemicals, and fumes

increases the risk of COPD in both smokers and nonsmokers. Workplace exposure is believed to be the cause in 10–20% of cases.

In the United States, it is believed that it is related to more than

30% of cases among those who have never smoked and probably represents a

greater risk in countries without sufficient regulations.

A number of industries and sources have been implicated, including high levels of dust in coal mining, gold mining, and the cotton textile industry, occupations involving cadmium and isocyanates, and fumes from welding. Working in agriculture is also a risk. In some professions, the risks have been estimated as equivalent to that of one-half to two packs of cigarettes a day. Silica dust and fiberglass dust exposure can also lead to COPD, with the risk unrelated to that for silicosis. The negative effects of dust exposure and cigarette smoke exposure appear to be additive or possibly more than additive.

Genetics

Genetics play a role in the development of COPD. It is more common among relatives of those with COPD who smoke than unrelated smokers. Currently, the only clearly inherited risk factor is alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (AAT). This risk is particularly high if someone deficient in alpha 1-antitrypsin also smokes. It is responsible for about 1–5% of cases and the condition is present in about three to four in 10,000 people. Other genetic factors are being investigated, of which many are likely.

Other

A number of

other factors are less closely linked to COPD. The risk is greater in

those who are poor, although whether this is due to poverty itself or other risk factors associated with poverty, such as air pollution and malnutrition, is not clear. Tentative evidence indicates that those with asthma and airway hyperreactivity are at increased risk of COPD. Birth factors such as low birth weight may also play a role, as do a number of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. Respiratory infections such as pneumonia do not appear to increase the risk of COPD, at least in adults.

Exacerbations

An acute exacerbation (a sudden worsening of symptoms)

is commonly triggered by infection or environmental pollutants, or

sometimes by other factors such as improper use of medications. Infections appear to be the cause of 50 to 75% of cases, with bacteria in 30%, viruses in 23%, and both in 25%.

Environmental pollutants include both poor indoor and outdoor air quality. Exposure to personal smoke and second-hand smoke increases the risk. Cold temperatures may also play a role, with exacerbations occurring more commonly in winter.

Those with more severe underlying disease have more frequent

exacerbations: in mild disease 1.8 per year, moderate 2 to 3 per year,

and severe 3.4 per year. Those with many exacerbations have a faster rate of deterioration of their lung function. A pulmonary embolism (PE) (blood clot in the lung) can worsen symptoms in those with pre-existing COPD. Signs of a PE in COPD include pleuritic chest pain and heart failure without signs of infection.

Pathophysiology

On the left is a diagram of the lungs and airways with an inset showing a detailed cross-section of normal

bronchioles and

alveoli. On the right are lungs damaged by COPD with an inset showing a cross-section of damaged bronchioles and alveoli.

COPD is a type of obstructive lung disease

in which chronic, incompletely reversible poor airflow (airflow

limitation) and inability to breathe out fully (air trapping) exist. The poor airflow is the result of breakdown of lung tissue (known as emphysema), and small airways disease known as obstructive bronchiolitis. The relative contributions of these two factors vary between people. Severe destruction of small airways can lead to the formation of large focal lung pneumatoses, known as bullae, that replace lung tissue. This form of disease is called bullous emphysema.

COPD develops as a significant and chronic inflammatory response to inhaled irritants. Chronic bacterial infections may also add to this inflammatory state. The inflammatory cells involved include neutrophil granulocytes and macrophages, two types of white blood cells. Those who smoke additionally have Tc1 lymphocyte involvement and some people with COPD have eosinophil involvement similar to that in asthma. Part of this cell response is brought on by inflammatory mediators such as chemotactic factors. Other processes involved with lung damage include oxidative stress produced by high concentrations of free radicals in tobacco smoke and released by inflammatory cells, and breakdown of the connective tissue of the lungs by proteases that are insufficiently inhibited by protease inhibitors.

The destruction of the connective tissue of the lungs leads to

emphysema, which then contributes to the poor airflow, and finally, poor

absorption and release of respiratory gases.

General muscle wasting that often occurs in COPD may be partly due to

inflammatory mediators released by the lungs into the blood.

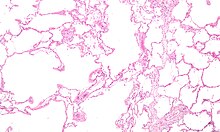

Micrograph showing emphysema (left – large empty spaces) and

lung tissue with relative preservation of the alveoli (right)

Narrowing of the airways occurs due to inflammation and scarring

within them. This contributes to the inability to breathe out fully. The

greatest reduction in air flow occurs when breathing out, as the

pressure in the chest is compressing the airways at this time.

This can result in more air from the previous breath remaining within

the lungs when the next breath is started, resulting in an increase in

the total volume of air in the lungs at any given time, a process called

hyperinflation or air trapping.

Hyperinflation from exercise is linked to shortness of breath in COPD,

as breathing in is less comfortable when the lungs are already partly

filled. Hyperinflation may also worsen during an exacerbation.

Some also have a degree of airway hyperresponsiveness to irritants similar to those found in asthma.

Low oxygen levels, and eventually, high carbon dioxide levels in the blood, can occur from poor gas exchange due to decreased ventilation from airway obstruction, hyperinflation, and a reduced desire to breathe.

During exacerbations, airway inflammation is also increased, resulting

in increased hyperinflation, reduced expiratory airflow, and worsening

of gas transfer. This can also lead to insufficient ventilation, and eventually low blood oxygen levels. Low oxygen levels, if present for a prolonged period, can result in narrowing of the arteries

in the lungs, while emphysema leads to breakdown of capillaries in the

lungs. Both of these changes result in increased blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries, which may cause right-sided heart failure secondary to lung disease, also known as cor pulmonale.

Diagnosis

A person blowing into a spirometer. Smaller handheld devices are available for office use.

The diagnosis of COPD should be considered in anyone over the age of 35 to 40 who has shortness of breath, a chronic cough, sputum production, or frequent winter colds and a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease. Spirometry is then used to confirm the diagnosis. Screening those without symptoms is not recommended.

Spirometry

Spirometry measures the amount of airflow obstruction present and is generally carried out after the use of a bronchodilator, a medication to open up the airways. Two main components are measured to make the diagnosis, the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), which is the greatest volume of air that can be breathed out in the first second of a breath, and the forced vital capacity (FVC), which is the greatest volume of air that can be breathed out in a single large breath. Normally, 75–80% of the FVC comes out in the first second and a FEV1/FVC ratio less than 70% in someone with symptoms of COPD defines a person as having the disease. Based on these measurements, spirometry would lead to over-diagnosis of COPD in the elderly. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence criteria additionally require a FEV1 less than 80% of predicted. People with COPD also exhibit a decrease in diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) due to decreased surface area in the alveoli, as well as damage to the capillary bed.

Evidence for using spirometry among those without symptoms in an effort to diagnose the condition earlier is of uncertain effect, so currently is not recommended. A peak expiratory flow (the maximum speed of expiration), commonly used in asthma, is not sufficient for the diagnosis of COPD.

Severity

MRC shortness of breath scale

| Grade |

Activity affected

|

| 1 |

Only strenuous activity

|

| 2 |

Vigorous walking

|

| 3 |

With normal walking

|

| 4 |

After a few minutes of walking

|

| 5 |

With changing clothing

|

GOLD grade

| Severity |

FEV1 % predicted

|

| Mild (GOLD 1) |

≥80

|

| Moderate (GOLD 2) |

50–79

|

| Severe (GOLD 3) |

30–49

|

| Very severe (GOLD 4) |

<30

|

A number of methods can determine how much COPD is affecting a given individual. The modified British Medical Research Council

questionnaire or the COPD assessment test (CAT) are simple

questionnaires that may be used to determine the severity of symptoms. Scores on CAT range from 0–40 with the higher the score, the more severe the disease. Spirometry may help to determine the severity of airflow limitation. This is typically based on the FEV1 expressed as a percentage of the predicted "normal" for the person's age, gender, height, and weight.

Both the American and European guidelines recommend partly basing treatment recommendations on the FEV1. The GOLD guidelines suggest dividing people into four categories based on symptoms assessment and airflow limitation. Weight loss and muscle weakness, as well as the presence of other diseases, should also be taken into account.

Other tests

A chest X-ray and complete blood count may be useful to exclude other conditions at the time of diagnosis. Characteristic signs on X-ray are hyperinflated lungs, a flattened diaphragm, increased retrosternal airspace, and bullae, while it can help exclude other lung diseases, such as pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or a pneumothorax. A high-resolution CT scan of the chest may show the distribution of emphysema throughout the lungs and can also be useful to exclude other lung diseases. Unless surgery is planned, however, this rarely affects management. A saber-sheath trachea deformity may also be present. An analysis of arterial blood is used to determine the need for oxygen; this is recommended in those with an FEV1

less than 35% predicted, those with a peripheral oxygen saturation less

than 92%, and those with symptoms of congestive heart failure.

In areas of the world where alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is common,

people with COPD (particularly those below the age of 45 and with

emphysema affecting the lower parts of the lungs) should be considered

for testing.

Chest X-ray demonstrating severe COPD: Note the small heart size in comparison to the lungs.

A lateral chest X-ray of a person with emphysema: Note the barrel chest and flat diaphragm.

Lung bulla as seen on chest X-ray in a person with severe COPD

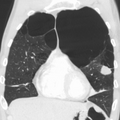

A severe case of bullous emphysema

Axial CT image of the lung of a person with end-stage bullous emphysema

Very severe emphysema with lung cancer on the left (CT scan)

Differential diagnosis

COPD may need to be differentiated from other causes of shortness of breath such as congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, or pneumothorax. Many people with COPD mistakenly think they have asthma.

The distinction between asthma and COPD is made on the basis of the

symptoms, smoking history, and whether airflow limitation is reversible

with bronchodilators at spirometry.

Tuberculosis may also present with a chronic cough and should be considered in locations where it is common. Less common conditions that may present similarly include bronchopulmonary dysplasia and obliterative bronchiolitis. Chronic bronchitis may occur with normal airflow and in this situation it is not classified as COPD.

Prevention

Most cases of COPD are potentially preventable through decreasing exposure to smoke and improving air quality. Annual influenza vaccinations in those with COPD reduce exacerbations, hospitalizations and death. Pneumococcal vaccination may also be beneficial. Eating a diet high in beta-carotene may help but taking supplements does not seem to. A review of an oral Haemophilus influenzae vaccine found 1.6 exacerbations per year as opposed to a baseline of 2.1 in those with COPD. This small reduction was not deemed significant.

Smoking cessation

Keeping people from starting smoking is a key aspect of preventing COPD. The policies

of governments, public health agencies, and antismoking organizations

can reduce smoking rates by discouraging people from starting and

encouraging people to stop smoking. Smoking bans

in public areas and places of work are important measures to decrease

exposure to secondhand smoke, and while many places have instituted

bans, more are recommended.

In those who smoke, stopping smoking is the only measure shown to slow down the worsening of COPD.

Even at a late stage of the disease, it can reduce the rate of

worsening lung function and delay the onset of disability and death. Often, several attempts are required before long-term abstinence is achieved. Attempts over 5 years lead to success in nearly 40% of people.

Some smokers can achieve long-term smoking cessation through willpower alone. Smoking, however, is highly addictive,

and many smokers need further support. The chance of quitting is

improved with social support, engagement in a smoking cessation program,

and the use of medications such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or varenicline.

Combining smoking-cessation medication with behavioral therapy is more

than twice as likely to be effective in helping people with COPD stop

smoking, compared with behavioral therapy alone.

Occupational health

A

number of measures have been taken to reduce the likelihood that

workers in at-risk industries—such as coal mining, construction, and

stonemasonry—will develop COPD. Examples of these measures include the creation of public policy, education of workers and management about the risks, promoting smoking cessation, checking workers for early signs of COPD, use of respirators, and dust control.

Effective dust control can be achieved by improving ventilation, using

water sprays and by using mining techniques that minimize dust

generation.

If a worker develops COPD, further lung damage can be reduced by

avoiding ongoing dust exposure, for example by changing their work role.

Air pollution

Both indoor and outdoor air quality can be improved, which may prevent COPD or slow the worsening of existing disease. This may be achieved by public policy efforts, cultural changes, and personal involvement.

A number of developed countries have successfully improved

outdoor air quality through regulations. This has resulted in

improvements in the lung function of their populations. Those with COPD may experience fewer symptoms if they stay indoors on days when outdoor air quality is poor.

One key effort is to reduce exposure to smoke from cooking and

heating fuels through improved ventilation of homes and better stoves

and chimneys. Proper stoves may improve indoor air quality by 85%. Using alternative energy sources such as solar cooking

and electrical heating is also effective. Using fuels such as kerosene

or coal might be less bad than traditional biomass such as wood or dung.

Management

No cure for COPD is known, but the symptoms are treatable and its progression can be delayed.

The major goals of management are to reduce risk factors, manage stable

COPD, prevent and treat acute exacerbations, and manage associated

illnesses. The only measures that have been shown to reduce mortality are smoking cessation and supplemental oxygen. Stopping smoking decreases the risk of death by 18%. Other recommendations include influenza vaccination once a year, pneumococcal vaccination once every five years, and reduction in exposure to environmental air pollution. In those with advanced disease, palliative care may reduce symptoms, with morphine improving the feelings of shortness of breath. Noninvasive ventilation may be used to support breathing.

Providing people with a personalized action plan, an educational

session, and support for use of their action plan in the event of an

exacerbation, reduces the number of hospital visits and encourages early

treatment of exacerbations.

When self-management interventions, such as taking corticosteroids and

using supplemental oxygen, is combined with action plans, health-related

quality of life is improved compared to usual care.

Self-management is also associated with improved health-related quality

of life, reduced respiratory-related and all-cause hospital admissions

and improvement in shortness of breath. The 2019 NICE guidelines also recommends treatment of associated conditions.

Exercise

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a program of exercise, disease management, and counseling, coordinated to benefit the individual.

In those who have had a recent exacerbation, pulmonary rehabilitation

appears to improve the overall quality of life and the ability to

exercise. If pulmonary rehabilitation improves mortality rates or hospital readmission rates is unclear.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve the sense of control

a person has over their disease, as well as their emotions.

The optimal exercise routine, use of noninvasive ventilation

during exercise, and intensity of exercise suggested for people with

COPD, is unknown.

Performing endurance arm exercises improves arm movement for people

with COPD, and may result in a small improvement in breathlessness. Performing arm exercises alone does not appear to improve quality of life. Breathing exercises in and of themselves appear to have a limited role. Pursed lip breathing exercises may be useful. Tai chi

exercises appear to be safe to practice for people with COPD, and may

be beneficial for pulmonary function and pulmonary capacity when

compared to a regular treatment program. Tai Chi was not found to be more effective than other exercise intervention programs.

Inspiratory and expiratory muscle training (IMT, EMT) is an effective

method for improving activities of daily living (ADL). A combination of

IMT and walking exercises at home may help limit breathlessness in cases

of severe COPD.

Additionally, the use of low amplitude high velocity joint mobilization

together with exercise improves lung function and exercise capacity.

The goal of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) is to improve thoracic

mobility in an effort to reduce the work on the lungs during

respiration, to in turn increase exercise capacity as indicated by the

results of a systemic medical review. Airway clearance techniques (ACTs), such as postural drainage, percussion/vibration, autogenic drainage, hand-held positive expiratory pressure

(PEP) devices and other mechanical devices, may reduce the need for

increased ventilatory assistance, the duration of ventilatory

assistance, and the length of hospital stay in people with acute COPD.

In people with stable COPD, ACTs may lead to short-term improvements in

health-related quality of life and a reduced long-term need for

hospitalisations related to respiratory issues.

Being either underweight or overweight can affect the symptoms,

degree of disability, and prognosis of COPD. People with COPD who are

underweight can improve their breathing muscle strength by increasing

their calorie intake.

When combined with regular exercise or a pulmonary rehabilitation

program, this can lead to improvements in COPD symptoms. Supplemental

nutrition may be useful in those who are malnourished.

Bronchodilators

Inhaled bronchodilators are the primary medications used, and result in a small overall benefit. The two major types are β2 agonists and anticholinergics; both exist in long-acting and short-acting forms. They reduce shortness of breath, wheeze, and exercise limitation, resulting in an improved quality of life. It is unclear if they change the progression of the underlying disease.

In those with mild disease, short-acting agents are recommended on an as needed basis. In those with more severe disease, long-acting agents are recommended. Long-acting agents partly work by reducing hyperinflation. If long-acting bronchodilators are insufficient, then inhaled corticosteroids are typically added. Which type of long-acting agent, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) such as tiotropium or a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) is better is unclear, and trying each and continuing with the one that works best may be advisable. Both types of agent appear to reduce the risk of acute exacerbations by 15–25%.

A 2018 review found the combination of LABA/LAMA may reduce COPD

exacerbations and improve quality-of-life compared to long-acting

bronchodilators alone.

The 2018 NICE guideline recommends use of dual long-acting

bronchodilators with economic modelling suggesting that this approach is

preferable to starting one long acting bronchodilator and adding

another later.

Several short-acting β2 agonists are available, including salbutamol (albuterol) and terbutaline. They provide some relief of symptoms for four to six hours. LABAs such as salmeterol, formoterol, and indacaterol are often used as maintenance therapy. Some feel the evidence of benefits is limited, while others view the evidence of benefit as established. Long-term use appears safe in COPD with adverse effects include shakiness and heart palpitations. When used with inhaled steroids they increase the risk of pneumonia. While steroids and LABAs may work better together, it is unclear if this slight benefit outweighs the increased risks. There is some evidence that combined treatment of LABAs with long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), an anticholinergic, may result in less exacerbations, less pneumonia, an improvement in forced expiratory volume (FEV1%), and potential improvements in quality of life when compared to treatment with LABA and an inhaled corticosteriod (ICS). All three together, LABA, LAMA, and ICS, have some evidence of benefits. Indacaterol requires an inhaled dose once a day, and is as effective as the other long-acting β2 agonist drugs that require twice-daily dosing for people with stable COPD.

Two main anticholinergics are used in COPD, ipratropium and tiotropium.

Ipratropium is a short-acting agent, while tiotropium is long-acting.

Tiotropium is associated with a decrease in exacerbations and improved

quality of life, and tiotropium provides those benefits better than ipratropium. It does not appear to affect mortality or the overall hospitalization rate. Anticholinergics can cause dry mouth and urinary tract symptoms. They are also associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.

Aclidinium, another long-acting agent, reduces hospitalizations associated with COPD and improves quality of life. The LAMA umeclidinium bromide is another anticholinergic alternative.

When compared to tiotropium, the LAMAs aclidinium, glycopyrronium, and

umeclidinium appear to have a similar level of efficacy; with all four

being more effective than placebo. Further research is needed comparing aclidinium to tiotropium.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids

are usually used in inhaled form, but may also be used as tablets to

treat acute exacerbations. While inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) have

not shown benefit for people with mild COPD, they decrease acute

exacerbations in those with either moderate or severe disease. By themselves, they have no effect on overall one-year mortality. Whether they affect the progression of the disease is unknown. When used in combination with a LABA, they may decrease mortality compared to either ICSs or LABA alone. Inhaled steroids are associated with increased rates of pneumonia. Long-term treatment with steroid tablets is associated with significant side effects.

The 2018 NICE guidelines recommend use of ICS in people with

asthmatic features or features suggesting steroid responsiveness. These

include any previous diagnosis of asthma or atopy, a higher blood

eosinophil count, substantial variation in FEV1 over time (at

least 400 mL) and at least 20% diurnal variation in peak expiratory

flow. “Higher” eosinophil count was chosen, rather than specifying a

particular value as it is not clear what the precise threshold should be

or on how many occasions or over what time period it should be

elevated.

Other medications

Long-term antibiotics, specifically those from the macrolide class such as erythromycin, reduce the frequency of exacerbations in those who have two or more a year. This practice may be cost effective in some areas of the world. Concerns include the potential for antibiotic resistance and side effects including hearing loss, tinnitus, and changes to the heart rhythm (long QT syndrome). Methylxanthines such as theophylline generally cause more harm than benefit and thus are usually not recommended, but may be used as a second-line agent in those not controlled by other measures. Mucolytics

may help to reduce exacerbations in some people with chronic

bronchitis; noticed by less hospitalization and less days of disability

in one month. Cough medicines are not recommended.

For people with COPD, the use of cardioselective (heart-specific) beta-blocker therapy does not appear to impair respiratory function. Cardioselective beta-blocker therapy should not be contraindicated for people with COPD. In those with low levels of vitamin D, supplementation appear to reduce the risk of exacerbations.

Oxygen

Supplemental oxygen is recommended in those with low oxygen levels at rest (a partial pressure of oxygen less than 50–55 mmHg or oxygen saturations of less than 88%). In this group of people, it decreases the risk of heart failure and death if used 15 hours per day and may improve people's ability to exercise.

In those with normal or mildly low oxygen levels, oxygen

supplementation may improve shortness of breath when given during

exercise, but may not improve breathlessness during normal daily

activities or affect the quality of life. A risk of fires and little benefit exist when those on oxygen continue to smoke. In this situation, some including NICE recommend against its use.

During acute exacerbations, many require oxygen therapy; the use of

high concentrations of oxygen without taking into account a person's

oxygen saturations may lead to increased levels of carbon dioxide and

worsened outcomes.

In those at high risk of high carbon dioxide levels, oxygen saturations

of 88–92% are recommended, while for those without this risk,

recommended levels are 94–98%.

Surgery

For those with very severe disease, surgery is sometimes helpful and may include lung transplantation or lung volume-reduction surgery,

which involves removing the parts of the lung most damaged by

emphysema, allowing the remaining, relatively good lung to expand and

work better.

It seems to be particularly effective if emphysema predominantly

involves the upper lobe, but the procedure increases the risks of

adverse events and early death for people who have diffuse emphysema. The procedure also increases the risk of adverse effects for people with moderate to severe COPD. Lung transplantation is sometimes performed for very severe COPD, particularly in younger individuals.

Exacerbations

Acute exacerbations are typically treated by increasing the use of short-acting bronchodilators. This commonly includes a combination of a short-acting inhaled beta agonist and anticholinergic. These medications can be given either via a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer or via a nebulizer, with both appearing to be equally effective. Nebulization may be easier for those who are more unwell. Oxygen supplementation can be useful. Excessive oxygen; however, can result in increased CO

2 levels and a decreased level of consciousness.

Corticosteroids by mouth improve the chance of recovery and decrease the overall duration of symptoms. They work equally well as intravenous steroids but appear to have fewer side effects. Five days of steroids work as well as ten or fourteen. In those with a severe exacerbation, antibiotics improve outcomes. A number of different antibiotics may be used including amoxicillin, doxycycline and azithromycin; whether one is better than the others is unclear. The FDA recommends against the use of fluoroquinolones when other options are available due to higher risks of serious side effects. There is no clear evidence for those with less severe cases.

For people with type 2 respiratory failure (acutely raised CO

2 levels) non-invasive positive pressure ventilation decreases the probability of death or the need of intensive care admission. Additionally, theophylline may have a role in those who do not respond to other measures. Fewer than 20% of exacerbations require hospital admission. In those without acidosis from respiratory failure, home care ("hospital at home") may be able to help avoid some admissions.

Prognosis

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease deaths per million persons in 2012

9–63

64–80

81–95

96–116

117–152

153–189

190–235

236–290

291–375

376–1089

Disability-adjusted life years lost to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.

| no data ≤110 110–220 220–330 330–440 440–550 550–660 | 660–770 770–880 880–990 990–1100 1100–1350 ≥1350 |

COPD usually gets gradually worse over time and can ultimately result in death. It is estimated that 3% of all disability is related to COPD.

The proportion of disability from COPD globally has decreased from 1990

to 2010 due to improved indoor air quality primarily in Asia. The overall number of years lived with disability from COPD, however, has increased.

The rate at which COPD worsens varies with the presence of

factors that predict a poor outcome, including severe airflow

obstruction, little ability to exercise, shortness of breath,

significant underweight or overweight, congestive heart failure, continued smoking, and frequent exacerbations. Long-term outcomes in COPD can be estimated using the BODE index which gives a score of zero to ten depending on FEV1, body-mass index, the distance walked in six minutes, and the modified MRC dyspnea scale. Significant weight loss is a bad sign.sults of spirometry are also a good predictor of the future progress of the disease but are not as good as the BODE index.

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, COPD affected approximately 329 million people (4.8% of the population). The disease affects men and women almost equally, as there has been increased tobacco use among women in the developed world.

The increase in the developing world between 1970 and the 2000s is

believed to be related to increasing rates of smoking in this region, an

increasing population and an aging population due to fewer deaths from

other causes such as infectious diseases. Some developed countries have seen increased rates, some have remained stable and some have seen a decrease in COPD prevalence. The global numbers are expected to continue increasing as risk factors remain common and the population continues to get older.

Between 1990 and 2010 the number of deaths from COPD decreased slightly from 3.1 million to 2.9 million and became the fourth leading cause of death. In 2012 it became the third leading cause as the number of deaths rose again to 3.1 million. In some countries, mortality has decreased in men but increased in women. This is most likely due to rates of smoking in women and men becoming more similar. COPD is more common in older people; it affects 34–200 out of 1000 people older than 65 years, depending on the population under review.

In England, an estimated 0.84 million people (of 50 million) have

a diagnosis of COPD; this translates into approximately one person in

59 receiving a diagnosis of COPD at some point in their lives. In the

most socioeconomically deprived parts of the country, one in 32 people

were diagnosed with COPD, compared with one in 98 in the most affluent

areas.

In the United States approximately 6.3% of the adult population,

totaling approximately 15 million people, have been diagnosed with COPD.

25 million people may have COPD if currently undiagnosed cases are included. In 2011, there were approximately 730,000 hospitalizations in the United States for COPD. In the United States, COPD is estimated to be the third leading cause of death in 2011.

History

The word "emphysema" is derived from the Greek ἐμφυσᾶν emphysan meaning "inflate" -itself composed of ἐν en, meaning "in", and φυσᾶν physan, meaning "breath, blast". The term "chronic bronchitis" came into use in 1808 while the term "COPD" is believed to have first been used in 1965.

Previously it has been known by a number of different names, including

chronic obstructive bronchopulmonary disease, chronic obstructive

respiratory disease, chronic airflow obstruction, chronic airflow

limitation, chronic obstructive lung disease, nonspecific chronic

pulmonary disease, and diffuse obstructive pulmonary syndrome. The terms

chronic bronchitis and emphysema were formally defined in 1959 at the CIBA guest symposium and in 1962 at the American Thoracic Society Committee meeting on Diagnostic Standards.

Early descriptions of probable emphysema include: in 1679 by T. Bonet of a condition of "voluminous lungs" and in 1769 by Giovanni Morgagni of lungs which were "turgid particularly from air". In 1721 the first drawings of emphysema were made by Ruysh. These were followed with pictures by Matthew Baillie in 1789 and descriptions of the destructive nature of the condition. In 1814 Charles Badham used "catarrh" to describe the cough and excess mucus in chronic bronchitis. René Laennec, the physician who invented the stethoscope, used the term "emphysema" in his book A Treatise on the Diseases of the Chest and of Mediate Auscultation

(1837) to describe lungs that did not collapse when he opened the chest

during an autopsy. He noted that they did not collapse as usual because

they were full of air and the airways were filled with mucus. In 1842, John Hutchinson invented the spirometer, which allowed the measurement of vital capacity

of the lungs. However, his spirometer could measure only volume, not

airflow. Tiffeneau and Pinelli in 1947 described the principles of

measuring airflow.

In 1953, Dr. George L. Waldbott, an American allergist, first

described a new disease he named "smoker's respiratory syndrome" in the

1953 Journal of the American Medical Association. This was the first association between tobacco smoking and chronic respiratory disease.

Early treatments included garlic, cinnamon and ipecac, among others. Modern treatments were developed during the second half of the 20th century. Evidence supporting the use of steroids in COPD was published in the late 1950s. Bronchodilators came into use in the 1960s following a promising trial of isoprenaline. Further bronchodilators, such as salbutamol, were developed in the 1970s, and the use of LABAs began in the mid-1990s.

Society and culture

COPD is known colloquially as "smoker's lung", but it may also occur in people who have never smoked. People with

emphysema have been known as "pink puffers" or "type A" due to their frequent pink complexion, fast respiratory rate and pursed lips, and people with

chronic bronchitis have been referred to as "blue bloaters" or "type B" due to the often

bluish color of the skin and lips from low oxygen levels and their swollen ankles.

This terminology is no longer accepted as useful as most people with

COPD have a combination of both emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Many health systems have difficulty ensuring appropriate identification, diagnosis and care of people with COPD; Britain's Department of Health has identified this as a major issue for the National Health Service and has introduced a specific strategy to tackle these problems.

Economics

Globally,

as of 2010, COPD is estimated to result in economic costs of

$2.1 trillion, half of which occurring in the developing world.

Of this total an estimated $1.9 trillion are direct costs such as

medical care, while $0.2 trillion are indirect costs such as missed

work. This is expected to more than double by the year 2030. In Europe, COPD represents 3% of healthcare spending. In the United States, costs of the disease are estimated at $50 billion, most of which is due to exacerbation. COPD was among the most expensive conditions seen in U.S. hospitals in 2011, with a total cost of about $5.7 billion.

Research

Mass spectrometry is being studied as a diagnostic tool in COPD.

Infliximab, an immune-suppressing antibody, has been tested in COPD; there was a possibility of harm with no evidence of benefit. Roflumilast, and cilomilast, are phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PDE4) and act as anti-inflammatories. They show promise in decreasing the rate of exacerbations, but do not appear to change a person's quality of life.

Roflumilast and cilomilast may be associated with side effects such as

gastrointestinal issues and weight loss. Sleep disturbances and mood

disturbances related to roflumilast have also been reported. A PDE4 is recommended to be used as an add-on therapy in case of failure of the standard COPD treatment during exacerbations.

Several new long-acting agents are under development. Treatment with stem cells is under study. While there is tentative data that it is safe, and the animal data is promising, there is little human data as of 2017. The small amount of human data there is has shown poor results.

A procedure known as targeted lung denervation, which involves decreasing the parasympathetic nervous system supply of the lungs, is being studied but does not have sufficient data to determine its use. The effectiveness of alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation treatment for people who have alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is unclear.

Research continues into the use of telehealthcare

to treat people with COPD when they experience episodes of shortness of

breath; treating people remotely may reduce the number of

emergency-room visits and improve the person's quality of life.