From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Cloud forcing (sometimes described as cloud radiative forcing) is, in meteorology, the difference between the radiation budget components for average cloud conditions and cloud-free conditions. Much of the interest in cloud forcing relates to its role as a feedback process in the present period of global warming.

All global climate models used for climate change projections include the effects of water vapor and cloud forcing. The models include the effects of clouds on both incoming (solar) and emitted (terrestrial) radiation.

Clouds increase the global reflection of solar radiation from 15% to 30%, reducing the amount of solar radiation absorbed by the Earth by about 44 W/m². This cooling is offset somewhat by the greenhouse effect of clouds which reduces the outgoing longwave radiation by about 31 W/m². Thus the net cloud forcing of the radiation budget is a loss of about 13 W/m².[1] If the clouds were removed with all else remaining the same, the Earth would gain this last amount in net radiation and begin to warm up. These numbers should not be confused with the usual radiative forcing concept, which is for the change in forcing related to climate change.

Without the inclusion of clouds, water vapor alone contributes 36% to 70% of the greenhouse effect on Earth. When water vapor and clouds are considered together, the contribution is 66% to 85%. The ranges come about because there are two ways to compute the influence of water vapor and clouds: the lower bounds are the reduction in the greenhouse effect if water vapor and clouds are removed from the atmosphere leaving all other greenhouse gases unchanged, while the upper bounds are the greenhouse effect introduced if water vapor and clouds are added to an atmosphere with no other greenhouse gases.[2] The two values differ because of overlap in the absorption and emission by the various greenhouse gases. Trapping of the long-wave radiation due to the presence of clouds reduces the radiative forcing of the greenhouse gases compared to the clear-sky forcing. However, the magnitude of the effect due to clouds varies for different greenhouse gases. Relative to clear skies, clouds reduce the global mean radiative forcing due to CO2 by about 15%,[3] that due to CH4 and N2O by about 20%,[3] and that due to the halocarbons by up to 30%.[4][5][6] Clouds remain one of the largest uncertainties in future projections of climate change by global climate models, owing to the physical complexity of cloud processes and the small scale of individual clouds relative to the size of the model computational grid.

All global climate models used for climate change projections include the effects of water vapor and cloud forcing. The models include the effects of clouds on both incoming (solar) and emitted (terrestrial) radiation.

Clouds increase the global reflection of solar radiation from 15% to 30%, reducing the amount of solar radiation absorbed by the Earth by about 44 W/m². This cooling is offset somewhat by the greenhouse effect of clouds which reduces the outgoing longwave radiation by about 31 W/m². Thus the net cloud forcing of the radiation budget is a loss of about 13 W/m².[1] If the clouds were removed with all else remaining the same, the Earth would gain this last amount in net radiation and begin to warm up. These numbers should not be confused with the usual radiative forcing concept, which is for the change in forcing related to climate change.

Without the inclusion of clouds, water vapor alone contributes 36% to 70% of the greenhouse effect on Earth. When water vapor and clouds are considered together, the contribution is 66% to 85%. The ranges come about because there are two ways to compute the influence of water vapor and clouds: the lower bounds are the reduction in the greenhouse effect if water vapor and clouds are removed from the atmosphere leaving all other greenhouse gases unchanged, while the upper bounds are the greenhouse effect introduced if water vapor and clouds are added to an atmosphere with no other greenhouse gases.[2] The two values differ because of overlap in the absorption and emission by the various greenhouse gases. Trapping of the long-wave radiation due to the presence of clouds reduces the radiative forcing of the greenhouse gases compared to the clear-sky forcing. However, the magnitude of the effect due to clouds varies for different greenhouse gases. Relative to clear skies, clouds reduce the global mean radiative forcing due to CO2 by about 15%,[3] that due to CH4 and N2O by about 20%,[3] and that due to the halocarbons by up to 30%.[4][5][6] Clouds remain one of the largest uncertainties in future projections of climate change by global climate models, owing to the physical complexity of cloud processes and the small scale of individual clouds relative to the size of the model computational grid.

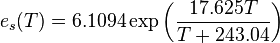

is the equilibrium or

is the equilibrium or  is temperature in degrees Celsius). This shows that when atmospheric temperature increases (e.g., due to

is temperature in degrees Celsius). This shows that when atmospheric temperature increases (e.g., due to