Criticism of the theory of relativity of Albert Einstein was mainly expressed in the early years after its publication in the early twentieth century, on scientific, pseudoscientific, philosophical, or ideological bases. Though some of these criticisms had the support of reputable scientists, Einstein's theory of relativity is now accepted by the scientific community.

Reasons for criticism of the theory of relativity have included alternative theories, rejection of the abstract-mathematical method, and alleged errors of the theory. According to some authors, antisemitic objections to Einstein's Jewish heritage also occasionally played a role in these objections. There are still some critics of relativity today, but their opinions are not shared by the majority in the scientific community.

Special relativity

Relativity principle versus electromagnetic worldview

Around the end of the 19th century, the view was widespread that all forces in nature are of electromagnetic origin (the "electromagnetic worldview"), especially in the works of Joseph Larmor (1897) and Wilhelm Wien (1900). This was apparently confirmed by the experiments of Walter Kaufmann (1901–1903), who measured an increase of the mass of a body with velocity which was consistent with the hypothesis that the mass was generated by its electromagnetic field. Max Abraham (1902) subsequently sketched a theoretical explanation of Kaufmann's result in which the electron was considered as rigid and spherical. However, it was found that this model was incompatible with the results of many experiments (including the Michelson–Morley experiment, the Experiments of Rayleigh and Brace, and the Trouton–Noble experiment), according to which no motion of an observer with respect to the luminiferous aether ("aether drift") had been observed despite numerous attempts to do so. Henri Poincaré (1902) conjectured that this failure arose from a general law of nature, which he called "the principle of relativity". Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1904) created a detailed theory of electrodynamics (Lorentz ether theory) that was premised on the existence of an immobile aether and employed a set of space and time coordinate transformations that Poincaré called the Lorentz transformations, including the effects of length contraction and local time. However, Lorentz's theory only partially satisfied the relativity principle, because his transformation formulas for velocity and charge density were incorrect. This was corrected by Poincaré (1905) who obtained full Lorentz covariance of the electrodynamic equations.

Criticizing Lorentz's 1904 theory, Abraham (1904) held that the Lorentz contraction of electrons requires a non-electromagnetic force to ensure the electron's stability. This was unacceptable to him as a proponent of the electromagnetic worldview. He continued that as long as a consistent explanation is missing as to how those forces and potentials act together on the electron, Lorentz's system of hypotheses is incomplete and doesn't satisfy the relativity principle. Poincaré (1905) removed this objection by showing that the non-electromagnetic potential ("Poincaré stress") holding the electron together can be formulated in a Lorentz covariant way, and showed that in principle it is possible to create a Lorentz covariant model for gravitation which he considered non-electromagnetic in nature as well. Thus the consistency of Lorentz's theory was proven, but the electromagnetic worldview had to be given up. Eventually, Albert Einstein published in September 1905 what is now called special relativity, which was based on a radical new application of the relativity principle in connection with the constancy of the speed of light. In special relativity, the space and time coordinates depend on the inertial observer's frame of reference, and the luminiferous aether plays no role in the physics. Although this theory was founded on a very different kinematical model, it was experimentally indistinguishable from the aether theory of Lorentz and Poincaré, since both theories satisfy the relativity principle of Poincaré and Einstein, and both employ the Lorentz transformations. After Minkowski's introduction in 1908 of the geometric spacetime model for Einstein's version of relativity, most physicists eventually decided in favor of the Einstein-Minkowski version of relativity with its radical new views of space and time, in which there was no useful role for the aether.

Claimed experimental refutations

Kaufmann–Bucherer–Neumann experiments: To conclusively decide between the theories of Abraham and Lorentz, Kaufmann repeated his experiments in 1905 with improved accuracy. However, in the meantime the theoretical situation had changed. Alfred Bucherer and Paul Langevin (1904) developed another model, in which the electron is contracted in the line of motion, and dilated in the transverse direction, so that the volume remains constant. While Kaufmann was still evaluating his experiments, Einstein published his theory of special relativity. Eventually, Kaufmann published his results in December 1905 and argued that they are in agreement with Abraham's theory and require rejection of the "basic assumption of Lorentz and Einstein" (the relativity principle). Lorentz reacted with the phrase "I am at the end of my Latin", while Einstein did not mention those experiments before 1908. Yet, others started to criticize the experiments. Max Planck (1906) alluded to inconsistencies in the theoretical interpretation of the data, and Adolf Bestelmeyer (1906) introduced new techniques, which (especially in the area of low velocities) gave different results and which cast doubts on Kaufmann's methods. Therefore, Bucherer (1908) conducted new experiments and arrived at the conclusion that they confirm the mass formula of relativity and thus the "relativity principle of Lorentz and Einstein". Yet Bucherer's experiments were criticized by Bestelmeyer leading to a sharp dispute between the two experimentalists. On the other hand, additional experiments of Hupka (1910), Neumann (1914) and others seemed to confirm Bucherer's result. The doubts lasted until 1940, when in similar experiments Abraham's theory was conclusively disproved. (It must be remarked that besides those experiments, the relativistic mass formula had already been confirmed by 1917 in the course of investigations on the theory of spectra. In modern particle accelerators, the relativistic mass formula is routinely confirmed.)

In 1902–1906, Dayton Miller repeated the Michelson–Morley experiment together with Edward W. Morley. They confirmed the null result of the initial experiment. However, in 1921–1926, Miller conducted new experiments which apparently gave positive results. Those experiments initially attracted some attention in the media and in the scientific community but have been considered refuted for the following reasons: Einstein, Max Born, and Robert S. Shankland pointed out that Miller had not appropriately considered the influence of temperature. A modern analysis by Roberts shows that Miller's experiment gives a null result, when the technical shortcomings of the apparatus and the error bars are properly considered. Additionally, Miller's result is in disagreement with all other experiments, which were conducted before and after. For example, Georg Joos (1930) used an apparatus of similar dimensions to Miller's, but he obtained null results. In recent experiments of Michelson–Morley type where the coherence length is increased considerably by using lasers and masers the results are still negative.

In the 2011 Faster-than-light neutrino anomaly, the OPERA collaboration published results which appeared to show that the speed of neutrinos is slightly faster than the speed of light. However, sources of errors were found and confirmed in 2012 by the OPERA collaboration, which fully explained the initial results. In their final publication, a neutrino speed consistent with the speed of light was stated. Also subsequent experiments found agreement with the speed of light, see measurements of neutrino speed.

Acceleration in special relativity

It was also claimed that special relativity cannot handle acceleration, which would lead to contradictions in some situations. However, this assessment is not correct, since acceleration actually can be described in the framework of special relativity (see Acceleration (special relativity), Proper reference frame (flat spacetime), Hyperbolic motion, Rindler coordinates, Born coordinates). Paradoxes relying on insufficient understanding of these facts were discovered in the early years of relativity. For example, Max Born (1909) tried to combine the concept of rigid bodies with special relativity. That this model was insufficient was shown by Paul Ehrenfest (1909), who demonstrated that a rotating rigid body would, according to Born's definition, undergo a contraction of the circumference without contraction of the radius, which is impossible (Ehrenfest paradox). Max von Laue (1911) showed that rigid bodies cannot exist in special relativity, since the propagation of signals cannot exceed the speed of light, so an accelerating and rotating body will undergo deformations.

Paul Langevin and von Laue showed that the twin paradox can be completely resolved by consideration of acceleration in special relativity. If two twins move away from each other, and one of them is accelerating and coming back to the other, then the accelerated twin is younger than the other one, since he was located in at least two inertial frames of reference, and therefore his assessment of which events are simultaneous changed during the acceleration. For the other twin nothing changes since he remained in a single frame. Another example is the Sagnac effect. Two signals were sent in opposite directions around a rotating platform. After their arrival a displacement of the interference fringes occurs. Sagnac himself believed that he had proved the existence of the aether. However, special relativity can easily explain this effect. When viewed from an inertial frame of reference, it is a simple consequence of the independence of the speed of light from the speed of the source, since the receiver runs away from one beam, while it approaches the other beam. When viewed from a rotating frame, the assessment of simultaneity changes during the rotation, and consequently the speed of light is not constant in accelerated frames.

As was shown by Einstein, the only form of accelerated motion that cannot be non-locally described is the one due to gravitation. Einstein was also unsatisfied with the fact that inertial frames are preferred over accelerated frames. Thus over the course of several years (1908–1915), Einstein developed general relativity. This theory includes the replacement of Euclidean geometry by non-Euclidean geometry, and the resultant curvature of the path of light led Einstein (1912) to the conclusion that (like in extended accelerated frames) the speed of light is not constant in extended gravitational fields. Therefore, Abraham (1912) argued that Einstein had given special relativity a coup de grâce. Einstein responded that within its area of application (in areas where gravitational influences can be neglected) special relativity is still applicable with high precision, so one cannot speak of a coup de grâce at all.

Superluminal speeds

In special relativity, the transfer of signals at superluminal speeds is impossible, since this would violate the Poincaré-Einstein synchronization, and the causality principle. Following an old argument by Pierre-Simon Laplace, Poincaré (1904) alluded to the fact that Newton's law of universal gravitation is founded on an infinitely great speed of gravity. So the clock-synchronization by light signals could in principle be replaced by a clock-synchronization by instantaneous gravitational signals. In 1905, Poincaré himself solved this problem by showing that in a relativistic theory of gravity the speed of gravity is equal to the speed of light. Although much more complicated, this is also the case in Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Another apparent contradiction lies in the fact that the group velocity in anomalously dispersive media is higher than the speed of light. This was investigated by Arnold Sommerfeld (1907, 1914) and Léon Brillouin (1914). They came to the conclusion that in such cases the signal velocity is not equal to the group velocity, but to the front velocity which is never faster than the speed of light. Similarly, it is also argued that the apparent superluminal effects discovered by Günter Nimtz can be explained by a thorough consideration of the velocities involved.

Also quantum entanglement (denoted by Einstein as "spooky action at a distance"), according to which the quantum state of one entangled particle cannot be fully described without describing the other particle, does not imply superluminal transmission of information (see quantum teleportation), and it is therefore in conformity with special relativity.

Paradoxes

Insufficient knowledge of the basics of special relativity, especially the application of the Lorentz transformation in connection with length contraction and time dilation, led and still leads to the construction of various apparent paradoxes. Both the twin paradox and the Ehrenfest paradox and their explanation were already mentioned above. Besides the twin paradox, also the reciprocity of time dilation (i.e. every inertially moving observer considers the clock of the other one as being dilated) was heavily criticized by Herbert Dingle and others. For example, Dingle wrote a series of letters to Nature at the end of the 1950s. However, the self-consistency of the reciprocity of time dilation had already been demonstrated long before in an illustrative way by Lorentz (in his lectures from 1910, published 1931) and many others—they alluded to the fact that it is only necessary to carefully consider the relevant measurement rules and the relativity of simultaneity. Other known paradoxes are the Ladder paradox and Bell's spaceship paradox, which also can simply be solved by consideration of the relativity of simultaneity.

Aether and absolute space

Many physicists (like Hendrik Lorentz, Oliver Lodge, Albert Abraham Michelson, Edmund Taylor Whittaker, Harry Bateman, Ebenezer Cunningham, Charles Émile Picard, Paul Painlevé) were uncomfortable with the rejection of the aether, and preferred to interpret the Lorentz transformation based on the existence of a preferred frame of reference, as in the aether-based theories of Lorentz, Larmor, and Poincaré. However, the idea of an aether hidden from any observation was not supported by the mainstream scientific community, therefore the aether theory of Lorentz and Poincaré was superseded by Einstein's special relativity which was subsequently formulated in the framework of four-dimensional spacetime by Minkowski.

Others such as Herbert E. Ives argued that it might be possible to experimentally determine the motion of such an aether, but it was never found despite numerous experimental tests of Lorentz invariance (see tests of special relativity).

Also attempts to introduce some sort of relativistic aether (consistent with relativity) into modern physics such as by Einstein on the basis of general relativity (1920), or by Paul Dirac in relation to quantum mechanics (1951), were not supported by the scientific community (see Luminiferous aether#End of aether?).

In his Nobel lecture, George F. Smoot (2006) described his own experiments on the Cosmic microwave background radiation anisotropy as "New Aether drift experiments". Smoot explained that "one problem to overcome was the strong prejudice of good scientists who learned the lesson of the Michelson and Morley experiment and Special Relativity that there were no preferred frames of reference." He continued that "there was an education job to convince them that this did not violate Special Relativity but did find a frame in which the expansion of the universe looked particularly simple."

Alternative theories

The theory of complete aether drag, as proposed by George Gabriel Stokes (1844), was used by some critics as Ludwig Silberstein (1920) or Philipp Lenard (1920) as a counter-model of relativity. In this theory, the aether was completely dragged within and in the vicinity of matter, and it was believed that various phenomena, such as the absence of aether drift, could be explained in an "illustrative" way by this model. However, such theories are subject to great difficulties. Especially the aberration of light contradicted the theory, and all auxiliary hypotheses, which were invented to rescue it, are self-contradictory, extremely implausible, or in contradiction to other experiments like the Michelson–Gale–Pearson experiment. In summary, a sound mathematical and physical model of complete aether drag was never invented, consequently this theory was no serious alternative to relativity.

Another alternative was the so-called emission theory of light. As in special relativity the aether concept is discarded, yet the main difference from relativity lies in the fact that the velocity of the light source is added to that of light in accordance with the Galilean transformation. As the hypothesis of complete aether drag, it can explain the negative outcome of all aether drift experiments. Yet, there are various experiments that contradict this theory. For example, the Sagnac effect is based on the independence of light speed from the source velocity, and the image of Double stars should be scrambled according to this model—which was not observed. Also in modern experiments in particle accelerators no such velocity dependence could be observed. These results are further confirmed by the De Sitter double star experiment (1913), conclusively repeated in the X-ray spectrum by K. Brecher in 1977; and the terrestrial experiment by Alväger, et al. (1963);, which all show that the speed of light is independent of the motion of the source within the limits of experimental accuracy.

Principle of the constancy of the speed of light

Some consider the principle of the constancy of the velocity of light insufficiently substantiated. However, as already shown by Robert Daniel Carmichael (1910) and others, the constancy of the speed of light can be interpreted as a natural consequence of two experimentally demonstrated facts:

- The velocity of light is independent of the velocity of the source, as demonstrated by De Sitter double star experiment, Sagnac effect, and many others (see emission theory).

- The velocity of light is independent of the direction of velocity of the observer, as demonstrated by Michelson–Morley experiment, Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, and many others (see luminiferous aether).

Note that measurements regarding the speed of light are actually measurements of the two-way speed of light, since the one-way speed of light depends on which convention is chosen to synchronize the clocks.

General relativity

General covariance

Einstein emphasized the importance of general covariance for the development of general relativity, and took the position that the general covariance of his 1915 theory of gravity ensured implementation of a generalized relativity principle. This view was challenged by Erich Kretschmann (1917), who argued that every theory of space and time (even including Newtonian dynamics) can be formulated in a covariant way, if additional parameters are included, and thus general covariance of a theory would in itself be insufficient to implement a generalized relativity principle. Although Einstein (1918) agreed with that argument, he also countered that Newtonian mechanics in general covariant form would be too complicated for practical uses. Although it is now understood that Einstein's response to Kretschmann was mistaken (subsequent papers showed that such a theory would still be usable), another argument can be made in favor of general covariance: it is a natural way to express the equivalence principle, i.e., the equivalence in the description of a free-falling observer and an observer at rest, and thus it is more convenient to use general covariance together with general relativity, rather than with Newtonian mechanics. Connected with this, also the question of absolute motion was dealt with. Einstein argued that the general covariance of his theory of gravity supports Mach's principle, which would eliminate any "absolute motion" within general relativity. However, as pointed out by Willem de Sitter in 1916, Mach's principle is not completely fulfilled in general relativity because there exist matter-free solutions of the field equations. This means that the "inertio-gravitational field", which describes both gravity and inertia, can exist in the absence of gravitating matter. However, as pointed out by Einstein, there is one fundamental difference between this concept and absolute space of Newton: the inertio-gravitational field of general relativity is determined by matter, thus it is not absolute.

Bad Nauheim Debate

In the "Bad Nauheim Debate" (1920) between Einstein and (among others) Philipp Lenard, the latter stated the following objections: He criticized the lack of "illustrativeness" of Einstein's version of relativity, a condition that he suggested could only be met by an aether theory. Einstein responded that for physicists the content of "illustrativeness" or "common sense" had changed in time, so it could no longer be used as a criterion for the validity of a physical theory. Lenard also argued that with his relativistic theory of gravity Einstein had tacitly reintroduced the aether under the name "space". While this charge was rejected (among others) by Hermann Weyl, in an inaugural address given at the University of Leiden in 1920, shortly after the Bad Nauheim debates, Einstein himself acknowledged that according to his general theory of relativity, so-called "empty space" possesses physical properties that influence matter and vice versa. Lenard also argued that Einstein's general theory of relativity admits the existence of superluminal velocities, in contradiction to the principles of special relativity; for example, in a rotating coordinate system in which the Earth is at rest, the distant points of the whole universe are rotating around Earth with superluminal velocities. However, as Weyl pointed out, it is incorrect to handle a rotating extended system as a rigid body (neither in special nor in general relativity)—so the signal velocity of an object never exceeds the speed of light. Another criticism that was raised by both Lenard and Gustav Mie concerned the existence of "fictitious" gravitational fields in accelerating frames, which according to Einstein's Equivalence Principle are no less physically real than those produced by material sources. Lenard and Mie argued that physical forces can only be produced by real material sources, while the gravitational field that Einstein supposed to exist in an accelerating frame of reference has no concrete physical meaning. Einstein responded that, based on Mach's principle, one can think of these gravitational fields as induced by the distant masses. In this respect the criticism of Lenard and Mie has been vindicated, since according to the modern consensus, in agreement with Einstein's own mature views, Mach's principle as originally conceived by Einstein is not actually supported by general relativity, as already mentioned above.

Silberstein–Einstein controversy

Ludwik Silberstein, who initially was a supporter of the special theory, objected at different occasions against general relativity. In 1920 he argued that the deflection of light by the sun, as observed by Arthur Eddington et al. (1919), is not necessarily a confirmation of general relativity, but may also be explained by the Stokes-Planck theory of complete aether drag. However, such models are in contradiction with the aberration of light and other experiments (see "Alternative theories"). In 1935, Silberstein claimed to have found a contradiction in the Two-body problem in general relativity. The claim was refuted by Einstein and Rosen (1935).

Philosophical criticism

The consequences of relativity, such as the change of ordinary concepts of space and time, as well as the introduction of non-Euclidean geometry in general relativity, were criticized by some philosophers of different philosophical schools. Many philosophical critics had insufficient knowledge of the mathematical and formal basis of relativity, which led to the criticisms often missing the heart of the matter. For example, relativity was misinterpreted as some form of relativism. However, this is misleading as it was emphasized by Einstein or Planck. On one hand it's true that space and time became relative, and the inertial frames of reference are handled on equal footing. On the other hand, the theory makes natural laws invariant—examples are the constancy of the speed of light, or the covariance of Maxwell's equations. Consequently, Felix Klein (1910) called it the "invariant theory of the Lorentz group" instead of relativity theory, and Einstein (who reportedly used expressions like "absolute theory") sympathized with this expression as well.

Critical responses to relativity were also expressed by proponents of neo-Kantianism (Paul Natorp, Bruno Bauch etc.), and phenomenology (Oskar Becker, Moritz Geiger etc.). While some of them only rejected the philosophical consequences, others rejected also the physical consequences of the theory. Einstein was criticized for violating Immanuel Kant's categoric scheme, i.e., it was claimed that space-time curvature caused by matter and energy is impossible, since matter and energy already require the concepts of space and time. Also the three-dimensionality of space, Euclidean geometry, and the existence of absolute simultaneity were claimed to be necessary for the understanding of the world; none of them can possibly be altered by empirical findings. By moving all those concepts into a metaphysical area, any form of criticism of Kantianism would be prevented. Other pseudo-Kantians like Ernst Cassirer or Hans Reichenbach (1920), tried to modify Kant's philosophy. Subsequently, Reichenbach rejected Kantianism at all and became a proponent of logical positivism.

Based on Henri Poincaré's conventionalism, philosophers such as Pierre Duhem (1914) and Hugo Dingler (1920) argued that the classical concepts of space, time, and geometry were, and will always be, the most convenient expressions in natural science, therefore the concepts of relativity cannot be correct. This was criticized by proponents of logical positivism such as Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, and Reichenbach. They argued that Poincaré's conventionalism could be modified to bring it into accord with relativity. Although it is true that the basic assumptions of Newtonian mechanics are simpler, it can only be brought into accord with modern experiments by inventing auxiliary hypotheses. On the other hand, relativity doesn't need such hypotheses, thus from a conceptual viewpoint, relativity is in fact simpler than Newtonian mechanics.

Some proponents of Philosophy of Life, Vitalism, Critical realism (in German speaking countries) argued that there is a fundamental difference between physical, biological and psychological phenomena. For example, Henri Bergson (1921), who otherwise was a proponent of special relativity, argued that time dilation cannot be applied to biological organisms, therefore he denied the relativistic solution of the twin paradox. However, those claims were rejected by Paul Langevin, André Metz and others. Biological organisms consist of physical processes, so there is no reason to assume that they are not subject to relativistic effects like time dilation.[A 38][B 37][C 21]

Based on the philosophy of Fictionalism, the philosopher Oskar Kraus (1921) and others claimed that the foundations of relativity were only fictitious and even self-contradictory. Examples were the constancy of the speed of light, time dilation, length contraction. These effects appear to be mathematically consistent as a whole, but in reality they allegedly are not true. Yet, this view was immediately rejected. The foundations of relativity (such as the equivalence principle or the relativity principle) are not fictitious, but based on experimental results. Also, effects like constancy of the speed of light and relativity of simultaneity are not contradictory, but complementary to one another.

In the Soviet Union (mostly in the 1920s), philosophical criticism was expressed on the basis of dialectic materialism. The theory of relativity was rejected as anti-materialistic and speculative, and a mechanistic worldview based on "common sense" was required as an alternative. Similar criticisms also occurred in the People's Republic of China during the Cultural Revolution. (On the other hand, other philosophers considered relativity as being compatible with Marxism.)

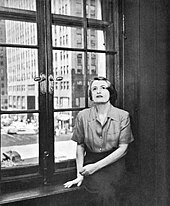

Relativity hype and popular criticism

Although Planck already in 1909 compared the changes brought about by relativity with the Copernican Revolution, and although special relativity was accepted by most of the theoretical physicists and mathematicians by 1911, it was not before publication of the experimental results of the eclipse expeditions (1919) by a group around Arthur Stanley Eddington that relativity was noticed by the public. Following Eddington's publication of the eclipse results, Einstein was glowingly praised in the mass media, and was compared to Nikolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, which caused a popular "relativity hype" ("Relativitätsrummel", as it was called by Sommerfeld, Einstein, and others). This triggered a counter-reaction of some scientists and scientific laymen who could not accept the concepts of modern physics, including relativity theory and quantum mechanics. The ensuing public controversy regarding the scientific status of Einstein's theory of gravity, which was unprecedented, was partly carried out in the press. Some of the criticism was not only directed to relativity, but personally at Einstein as well, who some of his critics accused of being behind the promotional campaign in the German press.

Academic and non-academic criticism

Some academic scientists, especially experimental physicists such as the Nobel laureates Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, as well as Ernst Gehrcke, Stjepan Mohorovičić, Rudolf Tomaschek and others criticized the increasing abstraction and mathematization of modern physics, especially in the form of relativity theory, and later quantum mechanics. It was seen as a tendency to abstract theory building, connected with the loss of intuitive "common sense". In fact, relativity was the first theory, in which the inadequacy of the "illustrative" classical physics was thought to have been demonstrated. Some of Einstein's critics ignored these developments and tried to revitalize older theories, such as aether drag models or emission theories (see "Alternative Theories"). However, those qualitative models were never sufficiently advanced to compete with the success of the precise experimental predictions and explanatory powers of the modern theories. Additionally, there was also a great rivalry between experimental and theoretical physicists, as regards the professorial activities and the occupation of chairs at German universities. The opinions clashed at the "Bad Nauheim debates" in 1920 between Einstein and (among others) Lenard, which attracted much public attention.

In addition, there were many critics (with or without physical training) whose ideas were far outside the scientific mainstream. These critics were mostly people who had developed their ideas long before the publication of Einstein's version of relativity, and they tried to resolve in a straightforward manner some or all of the enigmas of the world. Therefore, Wazeck (who studied some German examples) gave to these "free researchers" the name "world riddle solver" ("Welträtsellöser", such as Arvid Reuterdahl, Hermann Fricke or Johann Heinrich Ziegler). Their views had quite different roots in monism, Lebensreform, or occultism. Their views were typically characterized by the fact that they practically rejected the entire terminology and the (primarily mathematical) methods of modern science. Their works were published by private publishers, or in popular and non-specialist journals. It was significant for many "free researchers" (especially the monists) to explain all phenomena by intuitive and illustrative mechanical (or electrical) models, which also found its expression in their defense of the aether. For this reason they objected to the abstractness and inscrutability of the relativity theory, which was considered a pure calculation method that cannot reveal the true reasons underlying the phenomena. The "free researchers" often used Mechanical explanations of gravitation, in which gravity is caused by some sort of "aether pressure" or "mass pressure from a distance". Such models were regarded as an illustrative alternative to the abstract mathematical theories of gravitation of both Newton and Einstein. The enormous self-confidence of the "free researchers" is noteworthy, since they not only believed themselves to have solved the great riddles of the world, but many also seemed to expect that they would rapidly convince the scientific community.

Since Einstein rarely defended himself against these attacks, this task was undertaken by other relativity theoreticians, who (according to Hentschel) formed some sort of "defensive belt" around Einstein. Some representatives were Max von Laue, Max Born, etc. and on popular-scientific and philosophical level Hans Reichenbach, André Metz etc., who led many discussions with critics in semi-popular journals and newspapers. However, most of these discussions failed from the start. Physicists like Gehrcke, some philosophers, and the "free researchers" were so obsessed with their own ideas and prejudices that they were unable to grasp the basics of relativity; consequently, the participants of the discussions were talking past each other. In fact, the theory that was criticized by them was not relativity at all, but rather a caricature of it. The "free researchers" were mostly ignored by the scientific community, but also, in time, respected physicists such as Lenard and Gehrcke found themselves in a position outside the scientific community. However, the critics didn't believe that this was due to their incorrect theories, but rather due to a conspiracy of the relativistic physicists (and in the 1920s and 1930s of the Jews as well), which allegedly tried to put down the critics, and to preserve and improve their own positions within the academic world. For example, Gehrcke (1920/24) held that the propagation of relativity is a product of some sort of mass suggestion. Therefore, he instructed a media monitoring service to collect over 5000 newspaper clippings which were related to relativity, and published his findings in a book. However, Gehrcke's claims were rejected, because the simple existence of the "relativity hype" says nothing about the validity of the theory, and thus it cannot be used for or against relativity.

Afterward, some critics tried to improve their positions by the formation of alliances. One of them was the "Academy of Nations", which was founded in 1921 in the US by Robert T. Browne and Arvid Reuterdahl. Other members were Thomas Jefferson Jackson See and as well as Gehrcke and Mohorovičić in Germany. It is unknown whether other American critics such as Charles Lane Poor, Charles Francis Brush, Dayton Miller were also members. The alliance disappeared as early as the mid-1920s in Germany and by 1930 in the USA.

Chauvinism and antisemitism

Shortly before and during World War I, there appeared some nationalistically motivated criticisms of relativity and modern physics. For example, Pierre Duhem regarded relativity as the product of the "too formal and abstract" German spirit, which was in conflict with the "common sense". Similarly, popular criticism in the Soviet Union and China, which partly was politically organized, rejected the theory not because of factual objections, but as ideologically motivated as the product of western decadence.

So in those countries, the Germans or the Western civilization were the enemies. However, in Germany the Jewish ancestry of some leading relativity proponents such as Einstein and Minkowski made them targets of racially minded critics, although many of Einstein's German critics did not show evidence of such motives. The engineer Paul Weyland, a known nationalistic agitator, arranged the first public meeting against relativity in Berlin in 1919. While Lenard and Stark were also known for their nationalistic opinions, they declined to participate in Weyland's rallies, and Weyland's campaign eventually fizzled out due to a lack of prominent speakers. Lenard and others instead responded to Einstein's challenge to his professional critics to debate his theories at the scientific conference held annually at Bad Nauheim. While Einstein's critics, assuming without any real justification that Einstein was behind the activities of the German press in promoting the triumph of relativity, generally avoided antisemitic attacks in their earlier publications, it later became clear to many observers that antisemitism did play a significant role in some of the attacks.

Reacting to this underlying mood, Einstein himself openly speculated in a newspaper article that in addition to insufficient knowledge of theoretical physics, antisemitism at least partly motivated their criticisms. Some critics, including Weyland, reacted angrily and claimed that such accusations of antisemitism were only made to force the critics into silence. However, subsequently Weyland, Lenard, Stark and others clearly showed their antisemitic biases by beginning to combine their criticisms with racism. For example, Theodor Fritsch emphasized the alleged negative consequences of the "Jewish spirit" within relativity physics, and the far right-press continued this propaganda unhindered. After the murder of Walther Rathenau (1922) and murder threats against Einstein, he left Berlin for some time. Gehrcke's book on "The mass suggestion of relativity theory" (1924) was not antisemitic itself, but it was praised by the far-right press as describing an alleged typical Jewish behavior, which was also imputed to Einstein personally. Philipp Lenard in 1922 spoke about the "foreign spirit" as the foundation of relativity, and afterward he joined the Nazi party in 1924; Johannes Stark did the same in 1930. Both were proponents of the so-called German Physics, which only accepted scientific knowledge based on experiments, and only if accessible to the senses. According to Lenard (1936), this is the "Aryan physics or physics by man of Nordic kind" as opposed to the alleged formal-dogmatic "Jewish physics". Additional antisemitic critics can be found in the writings of Wilhelm Müller, Bruno Thüring and others. For example, Müller erroneously claimed that relativity was a purely "Jewish affair" and it would correspond to the "Jewish essence" etc., while Thüring made comparisons between the Talmud and relativity.

Accusations of plagiarism and priority discussions

Some of Einstein's critics, like Lenard, Gehrcke and Reuterdahl, accused him of plagiarism, and questioned his priority claims to the authorship of relativity theory. The thrust of such allegations was to promote more traditional alternatives to Einstein's abstract hypothetico-deductive approach to physics, while Einstein himself was to be personally discredited. It was argued by Einstein's supporters that such personal accusations were unwarranted, since the physical content and the applicability of former theories were quite different from Einstein's theory of relativity. However, others argued that between them Poincaré and Lorentz had earlier published several of the core elements of Einstein's 1905 relativity paper, including a generalized relativity principle that was intended by Poincaré to apply to all physics. Some examples:

- Johann Georg von Soldner (1801) was credited for his calculation of the deflection of light in the vicinity of celestial bodies, long before Einstein's prediction which was based on general relativity. However, Soldner's derivation has nothing to do with Einstein's, since it was fully based on Newton's theory, and only gave half of the value as predicted by general relativity.

- Paul Gerber (1898) published a formula for the perihelion advance of Mercury, which was formally identical to an approximate solution given by Einstein. However, since Einstein's formula was only an approximation, the solutions are not identical. In addition, Gerber's derivation has no connection with General relativity and was even regarded as meaningless.

- Woldemar Voigt (1887) derived a transformation, which is very similar to the Lorentz transformation. As Voigt himself acknowledged, his theory was not based on electromagnetic theory, but on an elastic aether model. His transformation also violates the relativity principle.

- Friedrich Hasenöhrl (1904) applied the concept of electromagnetic mass and momentum (which were known long before) to cavity radiation and thermal radiation. Yet, the applicability of Einstein's Mass–energy equivalence goes much further, since it is derived from the relativity principle and applies to all forms of energy.

- Menyhért Palágyi (1901) developed a philosophical "space-time" model in which time plays the role of an imaginary fourth dimension. Palágyi's model was only a reformulation of Newtonian physics, and had no connection to electromagnetic theory, the relativity principle, or to the constancy of the speed of light.

Some contemporary historians of science have revived the question as to whether Einstein was possibly influenced by the ideas of Poincaré, who first stated the relativity principle and applied it to electrodynamics, developing interpretations and modifications of Lorentz's electron theory that appear to have anticipated what is now called special relativity. Another discussion concerns a possible mutual influence between Einstein and David Hilbert as regards completing the field equations of general relativity (see Relativity priority dispute).

A Hundred Authors Against Einstein

A collection of various criticisms can be found in the book Hundert Autoren gegen Einstein (A Hundred Authors Against Einstein), published in 1931. It contains very short texts from 28 authors, and excerpts from the publications of another 19 authors. The rest consists of a list that also includes people who only for some time were opposed to relativity. From among Einstein's concepts the most targeted one is space-time followed by the speed of light as a constant and the relativity of simultaneity, with other concepts following. Besides philosophic objections (mostly based on Kantianism), also some alleged elementary failures of the theory were included; however, as some commented, those failures were due to the authors' misunderstanding of relativity. For example, Hans Reichenbach wrote a report in the entertainment section of a newspaper, describing the book as “a magnificent collection of naive mistakes” and as “unintended droll literature.” Albert von Brunn interpreted the book as a pamphlet "of such deplorable impotence as occurring elsewhere only in politics" and "a fallback into the 16th and 17th centuries" and concluded “it can only be hoped that German science will not again be embarrassed by such sad scribblings”, and Einstein said, in response to the book, that if he were wrong, then one author would have been enough.

According to Goenner, the contributions to the book are a mixture of mathematical–physical incompetence, hubris, and the feelings of the critics of being suppressed by contemporary physicists advocating the new theory. The compilation of the authors show, Goenner continues, that this was not a reaction within the physics community—only one physicist (Karl Strehl) and three mathematicians (Jean-Marie Le Roux, Emanuel Lasker and Hjalmar Mellin) were present—but a reaction of an inadequately educated academic citizenship, which didn't know what to do with relativity. As regards the average age of the authors: 57% were substantially older than Einstein, one third was around the same age, and only two persons were substantially younger. Two authors (Reuterdahl, von Mitis) were antisemitic and four others were possibly connected to the Nazi movement. On the other hand, no antisemitic expression can be found in the book, and it also included contributions of some authors of Jewish ancestry (Salomo Friedländer, Ludwig Goldschmidt, Hans Israel, Emanuel Lasker, Oskar Kraus, Menyhért Palágyi).

Status of criticism

The theory of relativity is considered to be self-consistent, is consistent with many experimental results, and serves as the basis of many successful theories like quantum electrodynamics. Therefore, fundamental criticism (like that of Herbert Dingle, Louis Essen, Petr Beckmann, Maurice Allais and Tom van Flandern) has not been taken seriously by the scientific community, and due to the lack of quality of many critical publications (found in the process of peer review) they were rarely accepted for publication in reputable scientific journals. Just as in the 1920s, most critical works are published in small publication houses, alternative journals (like "Apeiron" or "Galilean Electrodynamics"), or private websites. Consequently, where criticism of relativity has been dealt with by the scientific community, it has mostly been in historical studies.

However, this does not mean that there is no further development in modern physics. The progress of technology over time has led to extremely precise ways of testing the predictions of relativity, and so far it has successfully passed all tests (such as in particle accelerators to test special relativity, and by astronomical observations to test general relativity). In addition, in the theoretical field there is continuing research intended to unite general relativity and quantum theory, between which a fundamental incompatibility still remains. The most promising models are string theory and loop quantum gravity. Some variations of those models also predict violations of Lorentz invariance on a very small scale.