Religious violence in India includes acts of violence by followers of one religious group against followers and institutions of another religious group, often in the form of rioting. Religious violence in India has generally involved Hindus and Muslims.

Despite the secular and religiously tolerant constitution of India, broad religious representation in various aspects of society including the government, the active role played by autonomous bodies such as National Human Rights Commission of India and National Commission for Minorities, and the ground-level work being done by non-governmental organisations, sporadic and sometimes serious acts of religious violence tend to occur as the root causes of religious violence often run deep in history, religious activities, and politics of India.

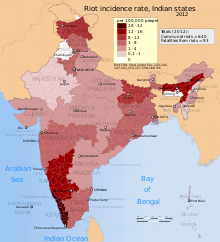

Along with domestic organizations, international human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch publish reports on acts of religious violence in India. From 2005 to 2009, an average of 130 people died every year from communal violence, or about 0.01 deaths per 100,000 population. The state of Maharashtra reported the highest total number of religious violence related fatalities over that five-year period, while Madhya Pradesh experienced the highest fatality rate per year per 100,000 population between 2005 and 2009. Over 2012, a total of 97 people died across India from various riots related to religious violence.

The US Commission on International Religious Freedom classified India as Tier-2 in persecuting religious minorities, the same as that of Iraq and Egypt. In a 2018 report, USCIRF charged Hindu nationalist groups for their campaign to "Saffronize" India through violence, intimidation, and harassment against non-Hindus. Approximately one-third of state governments enforced anti-conversion and/or anti-cow slaughter laws against non-Hindus, and mobs engaged in violence against Muslims whose families have been engaged in the dairy, leather, or beef trades for generations, and against Christians for proselytizing. "Cow protection" lynch mobs killed at least 10 victims in 2017.

Many historians argue that religious violence in independent India is a legacy of the policy of divide and rule pursued by the British colonial authorities during the era of Britain's control over the Indian subcontinent, in which local administrators pitted Hindus and Muslims against one another, a tactic that eventually culminated in the partition of India.

Ancient India

Ancient text Ashokavadana, a part of the Divyavadana, mention a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of Nirgrantha Jnatiputra (identified with Mahavira, 24th tirthankara of Jainism). On complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka, an emperor of the Maurya Dynasty, issued an order to arrest him, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order. Sometime later, another Nirgrantha follower in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house. He also announced an award of one dinara (silver coin) for the head of a Nirgrantha. According to Ashokavadana, as a result of this order, his own brother, Vitashoka, was mistaken for a heretic and killed by a cowherd. Their ministers advised that "this is an example of the suffering that is being inflicted even on those who are free from desire" and that he "should guarantee the security of all beings". After this, Ashoka stopped giving orders for executions. According to K. T. S. Sarao and Benimadhab Barua, stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be a clear fabrication arising out of sectarian propaganda.

The Divyavadana (divine stories), an anthology of Buddhist mythical tales on morals and ethics, many using talking birds and animals, was written in about 2nd century AD. In one of the stories, the razing of stupas and viharas is mentioned with Pushyamitra. This has been historically mapped to the reign of King Pushyamitra of the Shunga Empire about 400 years before Divyavadana was written. Archeological remains of stupas have been found in Deorkothar that suggest deliberate destruction, conjectured to be one mentioned in Divyavadana about Pushyamitra. It is unclear when the Deorkothar stupas were destroyed, and by whom. The fictional tales of Divyavadana is considered by scholars as being of doubtful value as a historical record. Moriz Winternitz, for example, stated, "these legends [in the Divyāvadāna] scarcely contain anything of much historical value".

Colonial Era

Goa Inquisition (1560–1774)

The first inquisitors, Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques, established themselves in what was formerly the king of Goa's palace, forcing the Portuguese viceroy to relocate to a smaller residence. The inquisitor's first act was forbidding Hindus from the public practice of their faith through fear of imprisonment. Sephardic Jews living in Goa, many of whom had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition to begin with, were also targeted. During the Goa Inquisition, described as "contrary to humanity" by anti-clerical Voltaire, conversion efforts were practiced en masse and tens of thousands of Goan people converted to Catholicism between 1561 and 1774. The few records that have survived suggest that around 57 were executed for their religious crime, and another 64 were burned in effigy because they had already died in jail before sentencing.

The adverse effects of the inquisition forced hundreds of Hindus, Muslims and Catholics to escape Portuguese hegemony by migrating to other parts of the subcontinent. Though officially repressed in 1774, it was nominally reinstated by Queen Maria I in 1778.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

In 1813, the East India Company charter was amended to allow for government sponsored missionary activity across British India. The missionaries soon spread almost everywhere and started denigrating Hindu and Islamic practices like Sati and child marriage, as well as promoting Christianity. Many officers of the British East India Company, such as Herbert Edwardes and Colonel S.G. Wheeler, openly preached to the Sepoys. Such activities caused a great deal of resentment and a fear of forced conversions among Indian soldiers of the Company and civilians alike.

There was a perception that the company was trying to convert Hindus and Muslims to Christianity, which is often cited as one of the causes of the revolt. The revolt is considered by some historians as a semi-national and semi-religious war seeking independence from British rule though Saul David questions this interpretation. The revolt started, among the Indian sepoys of British East India Company, when the British introduced new rifle cartridges, rumoured to be greased with pig and cow fat—an abhorrent concept to Muslim and Hindu soldiers, respectively, for religious reasons. 150,000 Indians and 6,000 Britons were killed during the 1857 rebellion.

Partition of Bengal (1905)

The British colonial era, since the 18th century, portrayed and treated Hindus and Muslims as two divided groups, both in cultural terms and for the purposes of governance. The British favoured Muslims in the early period of colonial rule to gain influence in Mughal India, but underwent a shift in policies after the 1857 rebellion. A series of religious riots in the late 19th century, such as those of 1891, 1896 and 1897 religious riots of Calcutta, raised concerns within British Raj. The rising political movement for independence of India, and colonial government's administrative strategies to neutralize it, pressed the British to make the first attempt to partition the most populous province of India, Bengal.

Bengal was partitioned by the British colonial government, in 1905, along religious lines—a Muslim majority state of East Bengal and a Hindu majority state of West Bengal. The partition was deeply resented, seen by both groups as evidence of British favoritism to the other side. Waves of religious riots hit Bengal through 1907. The religious violence worsened, and the partition was reversed in 1911. The reversal did little to calm the religious violence in India, and Bengal alone witnessed at least nine violent riots, between Muslims and Hindus, in the 1910s through the 1930s.

Moplah Rebellion (1921)

Moplah Rebellion was an Anti Jenmi rebellion conducted by the Muslim Moplah (Mappila) community of Kerala in 1921. Inspired by the Khilafat movement and the Karachi resolution; Moplahs murdered, pillaged, and forcibly converted thousands of Hindus. 100,000 Hindus were driven away from their homes forcing to leave their property behind, which were later taken over by Moplahs. This greatly changed the demographics of the area, being the major cause behind today's Malappuram district being a Muslim majority district in Kerala.

According to one view, the reasons for the Moplah rebellion was religious revivalism among the Muslim Moplahs, and hostility towards the landlord Hindu Nair, Nambudiri Jenmi community and the British administration that supported the latter. Adhering to view, British records call it a British-Muslim revolt. The initial focus was on the government, but when the limited presence of the government was eliminated, Moplahs turned their full attention on attacking Hindus. Mohommed Haji was proclaimed the Caliph of the Moplah Khilafat and flags of Islamic Caliphate were flown. Ernad and Walluvanad were declared Khilafat kingdoms.

Annie Besant wrote about the riots: "They Moplahs murdered and plundered abundantly, and killed or drove away all Hindus who would not apostatise. Somewhere about a lakh (100,000) of people were driven from their homes with nothing but their clothes they had on, stripped of everything. Malabar has taught us what Islamic rule still means, and we do not want to see another specimen of the Khilafat Raj in India."

Partition of British India (1947)

Direct Action Day, which started on 16 August 1946, left approximately 3,000 Hindus dead and 17,000 injured.

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British colonial government followed a divide-and-rule policy, exploiting existing differences between communities, to prevent similar revolts from taking place. In that respect, Indian Muslims were encouraged to forge a cultural and political identity separate from the Hindus. In the years leading up to Independence, Mohammad Ali Jinnah became increasingly concerned about minority position of Islam in an independent India largely composed of a Hindu majority.

Although a partition plan was accepted, no large population movements were contemplated. As India and Pakistan become independent, 14.5 million people crossed borders to ensure their safety in an increasingly lawless and communal environment. With British authority gone, the newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude, and massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border along communal lines. Estimates of the number of deaths range around roughly 500,000, with low estimates at 200,000 and high estimates at one million.

Modern India

Large-scale religious violence and riots have periodically occurred in India since its independence from British colonial rule. The aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947 to create a separate Islamic state of Pakistan for Muslims, saw large scale sectarian strife and bloodshed throughout the nation. Since then, India has witnessed sporadic large-scale violence sparked by underlying tensions between sections of the Hindu and Muslim communities. These conflicts also stem from the ideologies of hardline right-wing groups versus Islamic Fundamentalists and prevalent in certain sections of the population. Since independence, India has always maintained a constitutional commitment to secularism. The major incidences include the 1969 Gujarat riots, 1984 anti-Sikh riots, the 1989 Bhagalpur riots, 1989 Kashmir violence, Godhra train burning, 2002 Gujarat riots, 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots and 2020 Delhi riots.

Gujarat communal riots (1969)

Religious violence broke out between Hindus and Muslims during September–October 1969, in Gujarat. It was the most deadly Hindu-Muslim violence since the 1947 partition of India.

The violence included attacks on Muslim chawls by their Dalit neighbours. The violence continued over a week, then the rioting restarted a month later. Some 660 people were killed (430 Muslims, 230 Hindus), 1074 people were injured and over 48,000 lost their property.

Anti-Sikh riots (1984)

In the 1970s, Sikhs in Punjab had sought autonomy and complained about domination by the Hindu. Indira Gandhi government arrested thousands of Sikhs for their opposition and demands particularly during Indian Emergency. In Indira Gandhi's attempt to "save democracy" through the Emergency, India's constitution was suspended, 140,000 people were arrested without due process, of which 40,000 were Sikhs.

After the Emergency was lifted, during elections, she supported Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a Sikh leader, in an effort to undermine the Akali Dal, the largest Sikh political party. However, Bhindranwale began to oppose the central government and moved his political base to the Darbar Sahib (Golden temple) in Amritsar, demanding creation on Punjab as a new country. In June 1984, under orders from Indira Gandhi, the Indian army attacked the Golden temple with tanks and armoured vehicles, due to the presence of Sikh Khalistanis armed with weapons inside. Thousands of Sikhs died during the attack. In retaliation for the storming of the Golden temple, Indira Gandhi was assassinated on 31 October 1984 by two Sikh bodyguards.

The assassination provoked mass rioting against Sikh. During the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms in Delhi, government and police officials aided Indian National Congress party worker gangs in "methodically and systematically" targeting Sikhs and Sikh homes. As a result of the pogroms 10,000–17,000 were burned alive or otherwise killed, Sikh people suffered massive property damage, and at least 50,000 Sikhs were displaced.

The 1984 riots fueled the Sikh insurgency movement. In the peak years of the insurgency, religious violence by separatists, government-sponsored groups, and the paramilitary arms of the government was endemic on all sides. Human Rights Watch reports that separatists were responsible for "massacre of civilians, attacks upon Hindu minorities in the state, indiscriminate bomb attacks in crowded places, and the assassination of a number of political leaders". Human Rights Watch also stated that the Indian Government's response "led to the arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial execution, and enforced disappearance of thousands of Sikhs". The insurgency paralyzed Punjab's economy until peace initiatives and elections were held in the 1990s. Allegations of coverup and shielding of political leaders of Indian National Congress over their role in 1984 riot crimes, have been widespread.

Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus

In the Kashmir region, approximately 300 Kashmiri Pandits were killed between September 1989 to 1990 in various incidents. In early 1990, local Urdu newspapers Aftab and Al Safa called upon Kashmiris to wage jihad against India and ordered the expulsion of all Hindus choosing to remain in Kashmir. In the following days masked men ran in the streets with AK-47 shooting to kill Hindus who would not leave. Notices were placed on the houses of all Hindus, telling them to leave within 24 hours or die.

Since March 1990, estimates of between 300,000 and 500,000 pandits have migrated outside Kashmir due to persecution by Islamic fundamentalists in the largest case of ethnic cleansing since the partition of India.

Many Kashmiri Pandits have been killed by Islamist militants in incidents such as the Wandhama massacre and the 2000 Amarnath pilgrimage massacre. The incidents of massacring and forced eviction have been termed ethnic cleansing by some observers.

Religious involvement in North-East India militancy

Religion has begun to play an increasing role in reinforcing ethnic divides among the decades-old militant separatist movements in north-east India.

The Christian separatist group National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) has proclaimed bans on Hindu worship and has attacked animist Reangs and Hindu Jamatia tribesmen in the state of Tripura. Some resisting tribal leaders have been killed and some tribal women raped.

According to The Government of Tripura, the Baptist Church of Tripura is involved in supporting the NLFT and arrested two church officials in 2000, one of them for possessing explosives. In late 2004, the National Liberation Front of Tripura banned all Hindu celebrations of Durga Puja and Saraswati Puja. The Naga insurgency, militants have largely depended on their Christian ideological base for their cause.

Anti-Hindu violence

There have been a number of attacks on Hindu temples and Hindus by Muslim militants and Christian evangelists. Prominent among them are the 1998 Chamba massacre, the 2002 fidayeen attacks on Raghunath temple, the 2002 Akshardham Temple attack by Islamic terrorist outfit Lashkar-e-Toiba and the 2006 Varanasi bombings (also by Lashkar-e-Toiba), resulting in many deaths and injuries. Recent attacks on Hindus by Muslim mobs include Marad massacre and the Godhra train burning.

In August 2000, Swami Shanti Kali, a popular Hindu priest, was shot to death inside his ashram in the Indian state of Tripura. Police reports regarding the incident identified ten members of the Christian terrorist organisation, NLFT, as being responsible for the murder. On 4 Dec 2000, nearly three months after his death, an ashram set up by Shanti Kali at Chachu Bazar near the Sidhai police station was raided by Christian militants belonging to the NLFT. Eleven of the priest's ashrams, schools, and orphanages around the state were burned down by the NLFT.

In September 2008, Swami Laxmanananda, a popular regional Hindu Guru was murdered along with four of his disciples by unknown assailants (though a Maoist organisation later claimed responsibility for that). Later the police arrested three Christians in connection with the murder. Congress MP Radhakant Nayak has also been named as a suspected person in the murder, with some Hindu leaders calling for his arrest.

Lesser incidents of religious violence happen in many towns and villages in India. In October 2005, five people were killed in Mau in Uttar Pradesh during Muslim rioting, which was triggered by the proposed celebration of a Hindu festival.

On 3 and 4 January 2002, eight Hindus were killed in Marad, near Kozhikode due to scuffles between two groups that began after a dispute over drinking water. On 2 May 2003, eight Hindus were killed by a Muslim mob, in what is believed to be a sequel to the earlier incident. One of the attackers, Mohammed Ashker was killed during the chaos. The National Development Front (NDF), a right-wing militant Islamist organisation, was suspected as the perpetrator of the Marad massacre.

In the 2010 Deganga riots after hundreds of Hindu business establishments and residences were looted, destroyed and burnt, dozens of Hindus were killed or severely injured and several Hindu temples desecrated and vandalised by the Islamist mobs allegedly led by Trinamul Congress MP Haji Nurul Islam. Three years later, during the 2013 Canning riots, several hundred Hindu businesses were targeted and destroyed by Islamist mobs in the Indian state of West Bengal.

Religious violence has led to the death, injuries and damage to numerous Hindus. For example, 254 Hindus were killed in 2002 Gujarat riots out of which half were killed in police firing and rest by rioters. During 1992 Bombay riots, 275 Hindus died.

In October, 2018, a Christian personal security officer of an additional sessions judge assassinated his 38-year-old wife and his 18-year-old son for not converting to Christianity.

In October 2020, a 20-year old Nikita Tomar was shot by Tausif, a Muslim, for not converting to Islam and marrying to him. Tausif was imprisoned for life.

Some cases of murder because of blasphemy have also taken place. Kamlesh Tiwari was murdered for his allegedly blasphemous comments on Muhammad in October 2019. A similar case took place in Gujrat in January 2022 where Kishan Bharvad was murdered for making a allegedly blasphemous social media post on Muhammad on the directive of a Muslim cleric. A Hindu man named Nagaraju was murdered by a Muslim man for marrying a Muslim woman.

Violence against Muslims

The history of modern India has many incidents of communal violence. During the 1947 partition there was religious violence between Muslim-Hindu, Muslim-Sikhs and Muslim-Jains on a gigantic scale. Hundreds of religious riots have been recorded since then, in every decade of independent India. In these riots, the victims have included many Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Christians and Buddhists.

On 6 December 1992, members of the Vishva Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal destroyed the 430-year-old Babri Mosque in Ayodhya—it was claimed by the Hindus that the mosque was built over the birthplace of the ancient deity Rama (and a 2010 Allahabad court ruled that the site was indeed a Hindu monument before the mosque was built there, based on evidence submitted by the Archaeological Survey of India). The resulting religious riots caused at least 1200 deaths. Since then the Government of India has blocked off or heavily increased security at these disputed sites while encouraging attempts to resolve these disputes through court cases and negotiations.

In the aftermath of the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya by Hindu nationalists on 6 December 1992, riots took place between Hindus and Muslims in the city of Mumbai. Four people died in a fire in the Asalpha timber mart at Ghatkopar, five were killed in the burning of Bainganwadi; shacks along the harbour line track between Sewri and Cotton Green stations were gutted; and a couple was pulled out of a rickshaw in Asalpha village and burnt to death. The riots changed the demographics of Mumbai greatly, as Hindus moved to Hindu-majority areas and Muslims moved to Muslim-majority areas.

The Godhra train burning incident in which Hindus were burned alive allegedly by Muslims by closing door of train, led to the 2002 Gujarat riots in which mostly Muslims were killed. According to the death toll given to the parliament on 11 May 2005 by the United Progressive Alliance government, 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed, and another 2,548 injured. 223 people are missing. The report placed the number of riot widows at 919 and 606 children were declared orphaned. According to hone advocacy group, the death tolls were up to 2000. According to the Congressional Research Service, up to 2000 people were killed in the violence.

Tens of thousands were displaced from their homes because of the violence. According to New York Times reporter Celia Williams Dugger, witnesses were dismayed by the lack of intervention from local police, who often watched the events taking place and took no action against the attacks on Muslims and their property. Sangh leaders as well as the Gujarat government maintain that the violence was rioting or inter-communal clashes—spontaneous and uncontrollable reaction to the Godhra train burning.

The Government of India has implemented almost all the recommendations of the Sachar Committee to help Muslims.

The February 2020 North East Delhi riots, which left more than 40 dead and hundreds injured, were triggered by protests against a citizenship law seen by many critics as anti-Muslim and part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist agenda.

Anti-Christian violence

A 1999 Human Rights Watch report states increasing levels of religious violence on Christians in India, perpetrated by Hindu organizations. In 2000, acts of religious violence against Christians included forcible reconversion of converted Christians to Hinduism, distribution of threatening literature and destruction of Christian cemeteries. According to a 2008 report by Hudson Institute, "extremist Hindus have increased their attacks on Christians, until there are now several hundred per year. But this did not make news in the U.S. until a foreigner was attacked." In Orissa, starting December 2007, Christians have been attacked in Kandhamal and other districts, resulting in the deaths of two Hindus and one Christian, and the destruction of houses and churches. Hindus claim that Christians killed a Hindu saint Laxmananand, and the attacks on Christians were in retaliation. However, there was no conclusive proof to support this claim. Twenty people were arrested following the attacks on churches. Similarly, starting 14 September 2008, there were numerous incidents of violence against the Christian community in Karnataka.

In 2007, foreign Christian missionaries became targets of attacks.

Graham Stuart Staines (1941 – 23 January 1999) an Australian Christian missionary who, along with his two sons Philip (aged 10) and Timothy (aged 6), was burnt to death by a gang of Hindu Bajrang Dal fundamentalists while sleeping in his station wagon at Manoharpur village in Kendujhar district in Odisha, India on 23 January 1999. In 2003, a Bajrang Dal activist, Dara Singh, was convicted of leading the gang that murdered Graham Staines and his sons, and was sentenced to life in prison.

In its annual human rights reports for 1999, the United States Department of State criticised India for "increasing societal violence against Christians." The report listed over 90 incidents of anti-Christian violence, ranging from damage of religious property to violence against Christian pilgrims.

In Madhya Pradesh, unidentified persons set two statues inside St Peter and Paul Church in Jabalpur on fire. In Karnataka, religious violence was targeted against Christians in 2008.

Anti-atheist violence

Statistics

| Year | Incidents | Deaths | Injured |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 779 | 124 | 2066 |

| 2006 | 698 | 133 | 2170 |

| 2007 | 761 | 99 | 2227 |

| 2008 | 943 | 167 | 2354 |

| 2009 | 849 | 125 | 2461 |

| 2010 | 701 | 116 | 2138 |

| 2011 | 580 | 91 | 1899 |

| 2012 | 668 | 94 | 2117 |

| 2013 | 823 | 133 | 2269 |

| 2014 | 644 | 95 | 1921 |

| 2015 | 751 | 97 | 2264 |

| 2016 | 703 | 86 | 2321 |

| 2017 | 822 | 111 | 2384 |

From 2005 to 2009, an average of 130 people died every year from communal riots, and 2,200 were injured. In pre-partitioned India, over the 1920–1940 period, numerous communal violence incidents were recorded, an average of 381 people died per year during religious violence, and thousands were injured.

According to PRS India, 24 out of 35 states and union territories of India reported instances of religious riots over the five years from 2005 to 2009. However, most religious riots resulted in property damage but no injuries or fatalities. The highest incidences of communal violence in the five-year period were reported from Maharashtra (700). The other three states with high counts of communal violence over the same five-year period were Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Orissa. Together, these four states accounted for 64% of all deaths from communal violence. Adjusted for widely different population per state, the highest rate of communal violence fatalities were reported by Madhya Pradesh, at 0.14 death per 100,000 people over five years, or 0.03 deaths per 100,000 people per year. There was a wide regional variation in rate of death caused by communal violence per 100,000 people. The India-wide average communal violence fatality rate per year was 0.01 person per 100,000 people per year. The world's average annual death rate from intentional violence, in recent years, has been 7.9 per 100,000 people.

For 2012, there were 93 deaths in India from many incidences of communal violence (or 0.007 fatalities per 100,000 people). Of these, 48 were Muslims, 44 Hindus and one police official. The riots also injured 2,067 people, of which 1,010 were Hindus, 787 Muslims, 222 police officials and 48 others. Over 2013, 107 people were killed during religious riots (or 0.008 total fatalities per 100,000 people), of which 66 were Muslims, 41 were Hindus. The various riots in 2013 also injured 1,647 people including 794 Hindus, 703 Muslims and 200 policemen.

International human rights reports

- The 2007 United States Department of State International Religious Freedom Report noted The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the National Government generally respected this right in practice. However, some state and local governments limited this freedom in practice.

- The 2008 Human Rights Watch report notes: India claims an abiding commitment to human rights, but its record is marred by continuing violations by security forces in counterinsurgency operations and by government failure to rigorously implement laws and policies to protect marginalised communities. A vibrant media and civil society continue to press for improvements, but without tangible signs of success in 2007.

- The 2007 Amnesty International report listed several issues concern in India and noted Justice and rehabilitation continued to evade most victims of the 2002 Gujarat communal violence.

- The 2007 United States Department of State Human Rights Report noted that the government generally respected the rights of its citizens; however, numerous serious problems remained. The report which has received a lot of controversy internationally, as it does not include human rights violations of United States and its allies, has generally been rejected by political parties in India as interference in internal affairs, including in the Lower House of Parliament.

- In a 2018 report, United Nations Human Rights office expressed concerns over attacks directed at minorities and Dalits in India. The statement came in an annual report to the United Nations Human Rights Council's March 2018 session where Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein said,

"In India, I am increasingly disturbed by discrimination and violence directed at minorities, including Dalits and other scheduled castes, and religious minorities such as Muslims. In some cases this injustice appears actively endorsed by local or religious officials. I am concerned that criticism of government policies is frequently met by claims that it constitutes sedition or a threat to national security. I am deeply concerned by efforts to limit critical voices through the cancellation or suspension of registration of thousands of NGOs, including groups advocating for human rights and even public health groups."

In film and literature

Religious violence in India have been a topic of various films and novels.

- Firaaq, a film set in the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots

- Garam Hawa, a film by M. S. Sathyu based on a story on partition written by Ismat Chugtai

- Gandhi, a 1982 film which included portrayal of the Direct Action Day and Partition riots

- Tamas, a film on partition based on a book by Bhisham Sahni

- Bombay, a 1995 film centred on events during the period of December 1992 to January 1993 in India, and the controversy surrounding the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya

- Maachis, a film by Gulzar about Punjab terrorism

- Earth, a 1998 film portraying Partition violence in Lahore

- Fiza, a 2000 film set amidst the Bombay riots

- Hey Ram, a 2002 film with a semi-fictional plot centred around Partition of India and related religious violence

- Mr. and Mrs. Iyer, a 2002 film about the relationship between two lead characters Meenakshi Iyer and Raja amidst Hindu-Muslim riots in India

- Final Solution, a 2003 documentary film about the 2002 Gujarat violence, banned in India

- Hawayein, a 2003 film about the struggles of Sikhs during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots

- Black Friday, a Hindi film on the 1993 serial bomb blasts in Mumbai, directed by Anurag Kashyap

- Amu, a film about a girl orphaned during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots

- Parzania, a 2007 film about the riots in Gujarat in 2002 The film was purposely not released in Gujarat. Cinema owners and distributors in Gujarat refused to screen the film out of fear of retaliation by Hindu activists. Hindutva groups in Gujarat threatened to attack theatres that showed the film.

- Slumdog Millionaire, a 2008 British crime drama film that is a loose adaptation of the novel Q & A (2005) by Indian author Vikas Swarup, telling the story of 18-year-old Jamal Malik from the Juhu slums of Mumbai. The violence of the Bombay riots is an instrumental part of the plot of the film as the protagonist, Jamal Malik's mother is among those killed in the riots, and he later remarks "If it wasn't for Rama and Allah, we'd still have a mother."

- Train to Pakistan, a novel by Khushwant Singh set during the Partition of India, and a movie by the same name, based on the book

- "Toba Tek Singh", a satirical story by Saadat Hasan Manto set during the Partition of India

- Muzaffarnagar Abhi Baki Hai, a documentary on the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riot

- Punjab 1984, a 2014 Indian Punjabi period drama film based on the 1984–86 Punjab insurgency's impact on social life

- Man with the White Beard, 2018 fiction by Dr Shah Alam Khan set in the backdrop of three major riots of India: the anti Sikh riots of 1984, the anti Muslim riots of Gujarat in 2002 and the anti Christian riots of Kandhamal in 2008