Animal locomotion, in ethology, is any of a variety of methods that animals use to move from one place to another. Some modes of locomotion are (initially) self-propelled, e.g., running, swimming, jumping, flying, hopping, soaring and gliding. There are also many animal species that depend on their environment for transportation, a type of mobility called passive locomotion, e.g., sailing (some jellyfish), kiting (spiders), rolling (some beetles and spiders) or riding other animals (phoresis).

Animals move for a variety of reasons, such as to find food, a mate, a suitable microhabitat, or to escape predators. For many animals, the ability to move is essential for survival and, as a result, natural selection has shaped the locomotion methods and mechanisms used by moving organisms. For example, migratory animals that travel vast distances (such as the Arctic tern) typically have a locomotion mechanism that costs very little energy per unit distance, whereas non-migratory animals that must frequently move quickly to escape predators are likely to have energetically costly, but very fast, locomotion.

The anatomical structures that animals use for movement, including cilia, legs, wings, arms, fins, or tails are sometimes referred to as locomotory organs or locomotory structures.

Etymology

The term "locomotion" is formed in English from Latin loco "from a place" (ablative of locus "place") + motio "motion, a moving".

Locomotion in different media

Animals move through, or on, four types of environment: aquatic (in or on water), terrestrial (on ground or other surface, including arboreal, or tree-dwelling), fossorial (underground), and aerial (in the air). Many animals—for example semi-aquatic animals, and diving birds—regularly move through more than one type of medium. In some cases, the surface they move on facilitates their method of locomotion.

Aquatic

Swimming

In water, staying afloat is possible using buoyancy. If an animal's body is less dense than water, it can stay afloat. This requires little energy to maintain a vertical position, but requires more energy for locomotion in the horizontal plane compared to less buoyant animals. The drag encountered in water is much greater than in air. Morphology is therefore important for efficient locomotion, which is in most cases essential for basic functions such as catching prey. A fusiform, torpedo-like body form is seen in many aquatic animals, though the mechanisms they use for locomotion are diverse.

The primary means by which fish generate thrust is by oscillating the body from side-to-side, the resulting wave motion ending at a large tail fin. Finer control, such as for slow movements, is often achieved with thrust from pectoral fins (or front limbs in marine mammals). Some fish, e.g. the spotted ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) and batiform fish (electric rays, sawfishes, guitarfishes, skates and stingrays) use their pectoral fins as the primary means of locomotion, sometimes termed labriform swimming. Marine mammals oscillate their body in an up-and-down (dorso-ventral) direction. Other animals, e.g. penguins, diving ducks, move underwater in a manner which has been termed "aquatic flying". Some fish propel themselves without a wave motion of the body, as in the slow-moving seahorses and Gymnotus.

Other animals, such as cephalopods, use jet propulsion to travel fast, taking in water then squirting it back out in an explosive burst. Other swimming animals may rely predominantly on their limbs, much as humans do when swimming. Though life on land originated from the seas, terrestrial animals have returned to an aquatic lifestyle on several occasions, such as the fully aquatic cetaceans, now very distinct from their terrestrial ancestors.

Dolphins sometimes ride on the bow waves created by boats or surf on naturally breaking waves.

Benthic

Benthic locomotion is movement by animals that live on, in, or near the bottom of aquatic environments. In the sea, many animals walk over the seabed. Echinoderms primarily use their tube feet to move about. The tube feet typically have a tip shaped like a suction pad that can create a vacuum through contraction of muscles. This, along with some stickiness from the secretion of mucus, provides adhesion. Waves of tube feet contractions and relaxations move along the adherent surface and the animal moves slowly along. Some sea urchins also use their spines for benthic locomotion.

Crabs typically walk sideways (a behaviour that gives us the word crabwise). This is because of the articulation of the legs, which makes a sidelong gait more efficient. However, some crabs walk forwards or backwards, including raninids, Libinia emarginata and Mictyris platycheles. Some crabs, notably the Portunidae and Matutidae, are also capable of swimming, the Portunidae especially so as their last pair of walking legs are flattened into swimming paddles.

A stomatopod, Nannosquilla decemspinosa, can escape by rolling itself into a self-propelled wheel and somersault backwards at a speed of 72 rpm. They can travel more than 2 m using this unusual method of locomotion.

Aquatic surface

Velella, the by-the-wind sailor, is a cnidarian with no means of propulsion other than sailing. A small rigid sail projects into the air and catches the wind. Velella sails always align along the direction of the wind where the sail may act as an aerofoil, so that the animals tend to sail downwind at a small angle to the wind.

While larger animals such as ducks can move on water by floating, some small animals move across it without breaking through the surface. This surface locomotion takes advantage of the surface tension of water. Animals that move in such a way include the water strider. Water striders have legs that are hydrophobic, preventing them from interfering with the structure of water. Another form of locomotion (in which the surface layer is broken) is used by the basilisk lizard.

Aerial

Active flight

Gravity is the primary obstacle to flight. Because it is impossible for any organism to have a density as low as that of air, flying animals must generate enough lift to ascend and remain airborne. One way to achieve this is with wings, which when moved through the air generate an upward lift force on the animal's body. Flying animals must be very light to achieve flight, the largest living flying animals being birds of around 20 kilograms. Other structural adaptations of flying animals include reduced and redistributed body weight, fusiform shape and powerful flight muscles; there may also be physiological adaptations. Active flight has independently evolved at least four times, in the insects, pterosaurs, birds, and bats. Insects were the first taxon to evolve flight, approximately 400 million years ago (mya), followed by pterosaurs approximately 220 mya, birds approximately 160 mya, then bats about 60 mya.

Gliding

Rather than active flight, some (semi-) arboreal animals reduce their rate of falling by gliding. Gliding is heavier-than-air flight without the use of thrust; the term "volplaning" also refers to this mode of flight in animals. Thelphis mode of flight involves flying a greater distance horizontally than vertically and therefore can be distinguished from a simple descent like a parachute. Gliding has evolved on more occasions than active flight. There are examples of gliding animals in several major taxonomic classes such as the invertebrates (e.g., gliding ants), reptiles (e.g., banded flying snake), amphibians (e.g., flying frog), mammals (e.g., sugar glider, squirrel glider).

Some aquatic animals also regularly use gliding, for example, flying fish, octopus and squid. The flights of flying fish are typically around 50 meters (160 ft), though they can use updrafts at the leading edge of waves to cover distances of up to 400 m (1,300 ft). To glide upward out of the water, a flying fish moves its tail up to 70 times per second. Several oceanic squid, such as the Pacific flying squid, leap out of the water to escape predators, an adaptation similar to that of flying fish. Smaller squids fly in shoals, and have been observed to cover distances as long as 50 m. Small fins towards the back of the mantle help stabilize the motion of flight. They exit the water by expelling water out of their funnel, indeed some squid have been observed to continue jetting water while airborne providing thrust even after leaving the water. This may make flying squid the only animals with jet-propelled aerial locomotion. The neon flying squid has been observed to glide for distances over 30 m, at speeds of up to 11.2 m/s.

Soaring

Soaring birds can maintain flight without wing flapping, using rising air currents. Many gliding birds are able to "lock" their extended wings by means of a specialized tendon. Soaring birds may alternate glides with periods of soaring in rising air. Five principal types of lift are used: thermals, ridge lift, lee waves, convergences and dynamic soaring.

Examples of soaring flight by birds are the use of:

- Thermals and convergences by raptors such as vultures

- Ridge lift by gulls near cliffs

- Wave lift by migrating birds

- Dynamic effects near the surface of the sea by albatrosses

Ballooning

Ballooning is a method of locomotion used by spiders. Certain silk-producing arthropods, mostly small or young spiders, secrete a special light-weight gossamer silk for ballooning, sometimes traveling great distances at high altitude.

Terrestrial

Forms of locomotion on land include walking, running, hopping or jumping, dragging and crawling or slithering. Here friction and buoyancy are no longer an issue, but a strong skeletal and muscular framework are required in most terrestrial animals for structural support. Each step also requires much energy to overcome inertia, and animals can store elastic potential energy in their tendons to help overcome this. Balance is also required for movement on land. Human infants learn to crawl first before they are able to stand on two feet, which requires good coordination as well as physical development. Humans are bipedal animals, standing on two feet and keeping one on the ground at all times while walking. When running, only one foot is on the ground at any one time at most, and both leave the ground briefly. At higher speeds momentum helps keep the body upright, so more energy can be used in movement.Jumping

Jumping (saltation) can be distinguished from running, galloping, and other gaits where the entire body is temporarily airborne by the relatively long duration of the aerial phase and high angle of initial launch. Many terrestrial animals use jumping (including hopping or leaping) to escape predators or catch prey—however, relatively few animals use this as a primary mode of locomotion. Those that do include the kangaroo and other macropods, rabbit, hare, jerboa, hopping mouse, and kangaroo rat. Kangaroo rats often leap 2 m and reportedly up to 2.75 m at speeds up to almost 3 m/s (6.7 mph). They can quickly change their direction between jumps. The rapid locomotion of the banner-tailed kangaroo rat may minimize energy cost and predation risk. Its use of a "move-freeze" mode may also make it less conspicuous to nocturnal predators. Frogs are, relative to their size, the best jumpers of all vertebrates. The Australian rocket frog, Litoria nasuta, can leap over 2 metres (6 ft 7 in), more than fifty times its body length.

Peristalsis and looping

Other animals move in terrestrial habitats without the aid of legs. Earthworms crawl by a peristalsis, the same rhythmic contractions that propel food through the digestive tract.

Leeches and geometer moth caterpillars move by looping or inching (measuring off a length with each movement), using their paired circular and longitudinal muscles (as for peristalsis) along with the ability to attach to a surface at both anterior and posterior ends. One end is attached and the other end is projected forward peristaltically until it touches down, as far as it can reach; then the first end is released, pulled forward, and reattached; and the cycle repeats. In the case of leeches, attachment is by a sucker at each end of the body.

Sliding

Due to its low coefficient of friction, ice provides the opportunity for other modes of locomotion. Penguins either waddle on their feet or slide on their bellies across the snow, a movement called tobogganing, which conserves energy while moving quickly. Some pinnipeds perform a similar behaviour called sledding.

Climbing

Some animals are specialized for moving on non-horizontal surfaces. One common habitat for such climbing animals is in trees; for example, the gibbon is specialized for arboreal movement, travelling rapidly by brachiation (see below).

Others living on rock faces such as in mountains move on steep or even near-vertical surfaces by careful balancing and leaping. Perhaps the most exceptional are the various types of mountain-dwelling caprids (e.g., Barbary sheep, yak, ibex, rocky mountain goat, etc.), whose adaptations can include a soft rubbery pad between their hooves for grip, hooves with sharp keratin rims for lodging in small footholds, and prominent dew claws. Another case is the snow leopard, which being a predator of such caprids also has spectacular balance and leaping abilities, such as ability to leap up to 17 m (50 ft).

Some light animals are able to climb up smooth sheer surfaces or hang upside down by adhesion using suckers. Many insects can do this, though much larger animals such as geckos can also perform similar feats.

Walking and running

Species have different numbers of legs resulting in large differences in locomotion.

Modern birds, though classified as tetrapods, usually have only two functional legs, which some (e.g., ostrich, emu, kiwi) use as their primary, Bipedal, mode of locomotion. A few modern mammalian species are habitual bipeds, i.e., whose normal method of locomotion is two-legged. These include the macropods, kangaroo rats and mice, springhare, hopping mice, pangolins and homininan apes. Bipedalism is rarely found outside terrestrial animals—though at least two types of octopus walk bipedally on the sea floor using two of their arms, so they can use the remaining arms to camouflage themselves as a mat of algae or floating coconut.

There are no three-legged animals—though some macropods, such as kangaroos, that alternate between resting their weight on their muscular tails and their two hind legs could be looked at as an example of tripedal locomotion in animals.

Many familiar animals are quadrupedal, walking or running on four legs. A few birds use quadrupedal movement in some circumstances. For example, the shoebill sometimes uses its wings to right itself after lunging at prey. The newly hatched hoatzin bird has claws on its thumb and first finger enabling it to dexterously climb tree branches until its wings are strong enough for sustained flight. These claws are gone by the time the bird reaches adulthood.

A relatively few animals use five limbs for locomotion. Prehensile quadrupeds may use their tail to assist in locomotion and when grazing, the kangaroos and other macropods use their tail to propel themselves forward with the four legs used to maintain balance.

Insects generally walk with six legs—though some insects such as nymphalid butterflies do not use the front legs for walking.

Arachnids have eight legs. Most arachnids lack extensor muscles in the distal joints of their appendages. Spiders and whipscorpions extend their limbs hydraulically using the pressure of their hemolymph. Solifuges and some harvestmen extend their knees by the use of highly elastic thickenings in the joint cuticle. Scorpions, pseudoscorpions and some harvestmen have evolved muscles that extend two leg joints (the femur-patella and patella-tibia joints) at once.

The scorpion Hadrurus arizonensis walks by using two groups of legs (left 1, right 2, Left 3, Right 4 and Right 1, Left 2, Right 3, Left 4) in a reciprocating fashion. This alternating tetrapod coordination is used over all walking speeds.

Centipedes and millipedes have many sets of legs that move in metachronal rhythm. Some echinoderms locomote using the many tube feet on the underside of their arms. Although the tube feet resemble suction cups in appearance, the gripping action is a function of adhesive chemicals rather than suction. Other chemicals and relaxation of the ampullae allow for release from the substrate. The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one arm section attaching to the surface as another releases. Some multi-armed, fast-moving starfish such as the sunflower seastar (Pycnopodia helianthoides) pull themselves along with some of their arms while letting others trail behind. Other starfish turn up the tips of their arms while moving, which exposes the sensory tube feet and eyespot to external stimuli. Most starfish cannot move quickly, a typical speed being that of the leather star (Dermasterias imbricata), which can manage just 15 cm (6 in) in a minute. Some burrowing species from the genera Astropecten and Luidia have points rather than suckers on their long tube feet and are capable of much more rapid motion, "gliding" across the ocean floor. The sand star (Luidia foliolata) can travel at a speed of 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) per minute. Sunflower starfish are quick, efficient hunters, moving at a speed of 1 m/min (3.3 ft/min) using 15,000 tube feet.

Many animals temporarily change the number of legs they use for locomotion in different circumstances. For example, many quadrupedal animals switch to bipedalism to reach low-level browse on trees. The genus of Basiliscus are arboreal lizards that usually use quadrupedalism in the trees. When frightened, they can drop to water below and run across the surface on their hind limbs at about 1.5 m/s for a distance of approximately 4.5 m (15 ft) before they sink to all fours and swim. They can also sustain themselves on all fours while "water-walking" to increase the distance travelled above the surface by about 1.3 m. When cockroaches run rapidly, they rear up on their two hind legs like bipedal humans; this allows them to run at speeds up to 50 body lengths per second, equivalent to a "couple hundred miles per hour, if you scale up to the size of humans." When grazing, kangaroos use a form of pentapedalism (four legs plus the tail) but switch to hopping (bipedalism) when they wish to move at a greater speed.

Powered cartwheeling

The Moroccan flic-flac spider (Cebrennus rechenbergi) uses a series of rapid, acrobatic flic-flac movements of its legs similar to those used by gymnasts, to actively propel itself off the ground, allowing it to move both down and uphill, even at a 40 percent incline. This behaviour is different than other huntsman spiders, such as Carparachne aureoflava from the Namib Desert, which uses passive cartwheeling as a form of locomotion. The flic-flac spider can reach speeds of up to 2 m/s using forward or back flips to evade threats.

Subterranean

Some animals move through solids such as soil by burrowing using peristalsis, as in earthworms, or other methods. In loose solids such as sand some animals, such as the golden mole, marsupial mole, and the pink fairy armadillo, are able to move more rapidly, "swimming" through the loose substrate. Burrowing animals include moles, ground squirrels, naked mole-rats, tilefish, and mole crickets.

Arboreal locomotion

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. Some animals may only scale trees occasionally, while others are exclusively arboreal. These habitats pose numerous mechanical challenges to animals moving through them, leading to a variety of anatomical, behavioural and ecological consequences as well as variations throughout different species. Furthermore, many of these same principles may be applied to climbing without trees, such as on rock piles or mountains. The earliest known tetrapod with specializations that adapted it for climbing trees was Suminia, a synapsid of the late Permian, about 260 million years ago. Some invertebrate animals are exclusively arboreal in habitat, for example, the tree snail.

Brachiation (from brachium, Latin for "arm") is a form of arboreal locomotion in which primates swing from tree limb to tree limb using only their arms. During brachiation, the body is alternately supported under each forelimb. This is the primary means of locomotion for the small gibbons and siamangs of southeast Asia. Some New World monkeys such as spider monkeys and muriquis are "semibrachiators" and move through the trees with a combination of leaping and brachiation. Some New World species also practice suspensory behaviors by using their prehensile tail, which acts as a fifth grasping hand.

Energetics

Animal locomotion requires energy to overcome various forces including friction, drag, inertia and gravity, although the influence of these depends on the circumstances. In terrestrial environments, gravity must be overcome whereas the drag of air has little influence. In aqueous environments, friction (or drag) becomes the major energetic challenge with gravity being less of an influence. Remaining in the aqueous environment, animals with natural buoyancy expend little energy to maintain a vertical position in a water column. Others naturally sink, and must spend energy to remain afloat. Drag is also an energetic influence in flight, and the aerodynamically efficient body shapes of flying birds indicate how they have evolved to cope with this. Limbless organisms moving on land must energetically overcome surface friction, however, they do not usually need to expend significant energy to counteract gravity.

Newton's third law of motion is widely used in the study of animal locomotion: if at rest, to move forwards an animal must push something backwards. Terrestrial animals must push the solid ground, swimming and flying animals must push against a fluid (either water or air). The effect of forces during locomotion on the design of the skeletal system is also important, as is the interaction between locomotion and muscle physiology, in determining how the structures and effectors of locomotion enable or limit animal movement. The energetics of locomotion involves the energy expenditure by animals in moving. Energy consumed in locomotion is not available for other efforts, so animals typically have evolved to use the minimum energy possible during movement. However, in the case of certain behaviors, such as locomotion to escape a predator, performance (such as speed or maneuverability) is more crucial, and such movements may be energetically expensive. Furthermore, animals may use energetically expensive methods of locomotion when environmental conditions (such as being within a burrow) preclude other modes.

The most common metric of energy use during locomotion is the net (also termed "incremental") cost of transport, defined as the amount of energy (e.g., Joules) needed above baseline metabolic rate to move a given distance. For aerobic locomotion, most animals have a nearly constant cost of transport—moving a given distance requires the same caloric expenditure, regardless of speed. This constancy is usually accomplished by changes in gait. The net cost of transport of swimming is lowest, followed by flight, with terrestrial limbed locomotion being the most expensive per unit distance. However, because of the speeds involved, flight requires the most energy per unit time. This does not mean that an animal that normally moves by running would be a more efficient swimmer; however, these comparisons assume an animal is specialized for that form of motion. Another consideration here is body mass—heavier animals, though using more total energy, require less energy per unit mass to move. Physiologists generally measure energy use by the amount of oxygen consumed, or the amount of carbon dioxide produced, in an animal's respiration. In terrestrial animals, the cost of transport is typically measured while they walk or run on a motorized treadmill, either wearing a mask to capture gas exchange or with the entire treadmill enclosed in a metabolic chamber. For small rodents, such as deer mice, the cost of transport has also been measured during voluntary wheel running.

Energetics is important for explaining the evolution of foraging economic decisions in organisms; for example, a study of the African honey bee, A. m. scutellata, has shown that honey bees may trade the high sucrose content of viscous nectar off for the energetic benefits of warmer, less concentrated nectar, which also reduces their consumption and flight time.

Passive locomotion

Passive locomotion in animals is a type of mobility in which the animal depends on their environment for transportation; such animals are vagile but not motile.

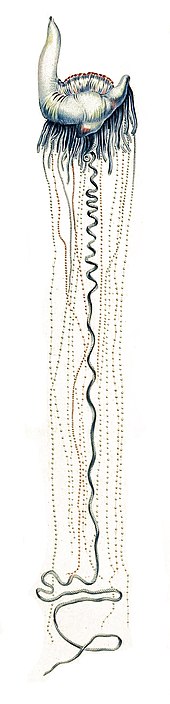

Hydrozoans

The Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis) lives at the surface of the ocean. The gas-filled bladder, or pneumatophore (sometimes called a "sail"), remains at the surface, while the remainder is submerged. Because the Portuguese man o' war has no means of propulsion, it is moved by a combination of winds, currents, and tides. The sail is equipped with a siphon. In the event of a surface attack, the sail can be deflated, allowing the organism to briefly submerge.

Mollusca

The violet sea-snail (Janthina janthina) uses a buoyant foam raft stabilized by amphiphilic mucins to float at the sea surface.

Arachnids

The wheel spider (Carparachne aureoflava) is a huntsman spider approximately 20 mm in size and native to the Namib Desert of Southern Africa. The spider escapes parasitic pompilid wasps by flipping onto its side and cartwheeling down sand dunes at speeds of up to 44 turns per second. If the spider is on a sloped dune, its rolling speed may be 1 metre per second.

A spider (usually limited to individuals of a small species), or spiderling after hatching, climbs as high as it can, stands on raised legs with its abdomen pointed upwards ("tiptoeing"), and then releases several silk threads from its spinnerets into the air. These form a triangle-shaped parachute that carries the spider on updrafts of winds, where even the slightest breeze transports it. The Earth's static electric field may also provide lift in windless conditions.

Insects

The larva of Cicindela dorsalis, the eastern beach tiger beetle, is notable for its ability to leap into the air, loop its body into a rotating wheel and roll along the sand at a high speed using wind to propel itself. If the wind is strong enough, the larva can cover up to 60 metres (200 ft) in this manner. This remarkable ability may have evolved to help the larva escape predators such as the thynnid wasp Methocha.

Members of the largest subfamily of cuckoo wasps, Chrysidinae, are generally kleptoparasites, laying their eggs in host nests, where their larvae consume the host egg or larva while it is still young. Chrysidines are distinguished from the members of other subfamilies in that most have flattened or concave lower abdomens and can curl into a defensive ball when attacked by a potential host, a process known as conglobation. Protected by hard chitin in this position, they are expelled from the nest without injury and can search for a less hostile host.

Fleas can jump vertically up to 18 cm and horizontally up to 33 cm; however, although this form of locomotion is initiated by the flea, it has little control of the jump—they always jump in the same direction, with very little variation in the trajectory between individual jumps.

Crustaceans

Although stomatopods typically display the standard locomotion types as seen in true shrimp and lobsters, one species, Nannosquilla decemspinosa, has been observed flipping itself into a crude wheel. The species lives in shallow, sandy areas. At low tides, N. decemspinosa is often stranded by its short rear legs, which are sufficient for locomotion when the body is supported by water, but not on dry land. The mantis shrimp then performs a forward flip in an attempt to roll towards the next tide pool. N. decemspinosa has been observed to roll repeatedly for 2 m (6.6 ft), but they typically travel less than 1 m (3.3 ft). Again, the animal initiates the movement but has little control during its locomotion.

Animal transport

Some animals change location because they are attached to, or reside on, another animal or moving structure. This is arguably more accurately termed "animal transport".

Remoras

Remoras are a family (Echeneidae) of ray-finned fish. They grow to 30–90 cm (0.98–2.95 ft) long, and their distinctive first dorsal fins take the form of a modified oval, sucker-like organ with slat-like structures that open and close to create suction and take a firm hold against the skin of larger marine animals. By sliding backward, the remora can increase the suction, or it can release itself by swimming forward. Remoras sometimes attach to small boats. They swim well on their own, with a sinuous, or curved, motion. When the remora reaches about 3 cm (1.2 in), the disc is fully formed and the remora can then attach to other animals. The remora's lower jaw projects beyond the upper, and the animal lacks a swim bladder. Some remoras associate primarily with specific host species. They are commonly found attached to sharks, manta rays, whales, turtles, and dugongs. Smaller remoras also fasten onto fish such as tuna and swordfish, and some small remoras travel in the mouths or gills of large manta rays, ocean sunfish, swordfish, and sailfish. The remora benefits by using the host as transport and protection, and also feeds on materials dropped by the host.

Angler fish

In some species of anglerfish, when a male finds a female, he bites into her skin, and releases an enzyme that digests the skin of his mouth and her body, fusing the pair down to the blood-vessel level. The male becomes dependent on the female host for survival by receiving nutrients via their shared circulatory system, and provides sperm to the female in return. After fusing, males increase in volume and become much larger relative to free-living males of the species. They live and remain reproductively functional as long as the female lives, and can take part in multiple spawnings. This extreme sexual dimorphism ensures, when the female is ready to spawn, she has a mate immediately available. Multiple males can be incorporated into a single individual female with up to eight males in some species, though some taxa appear to have a one male per female rule.

Parasites

Many parasites are transported by their hosts. For example, endoparasites such as tapeworms live in the alimentary tracts of other animals, and depend on the host's ability to move to distribute their eggs. Ectoparasites such as fleas can move around on the body of their host, but are transported much longer distances by the host's locomotion. Some ectoparasites such as lice can opportunistically hitch a ride on a fly (phoresis) and attempt to find a new host.

Changes between media

Some animals locomote between different media, e.g., from aquatic to aerial. This often requires different modes of locomotion in the different media and may require a distinct transitional locomotor behaviour.

There are a large number of semi-aquatic animals (animals that spend part of their life cycle in water, or generally have part of their anatomy underwater). These represent the major taxa of mammals (e.g., beaver, otter, polar bear), birds (e.g., penguins, ducks), reptiles (e.g., anaconda, bog turtle, marine iguana) and amphibians (e.g., salamanders, frogs, newts).

Fish

Some fish use multiple modes of locomotion. Walking fish may swim freely or at other times "walk" along the ocean or river floor, but not on land (e.g., the flying gurnard—which does not actually fly—and batfishes of the family Ogcocephalidae). Amphibious fish, are fish that are able to leave water for extended periods of time. These fish use a range of terrestrial locomotory modes, such as lateral undulation, tripod-like walking (using paired fins and tail), and jumping. Many of these locomotory modes incorporate multiple combinations of pectoral, pelvic and tail fin movement. Examples include eels, mudskippers and the walking catfish. Flying fish can make powerful, self-propelled leaps out of water into air, where their long, wing-like fins enable gliding flight for considerable distances above the water's surface. This uncommon ability is a natural defence mechanism to evade predators. The flights of flying fish are typically around 50 m, though they can use updrafts at the leading edge of waves to cover distances of up to 400 m (1,300 ft). They can travel at speeds of more than 70 km/h (43 mph). Maximum altitude is 6 m (20 ft) above the surface of the sea. Some accounts have them landing on ships' decks.

Marine mammals

When swimming, several marine mammals such as dolphins, porpoises and pinnipeds, frequently leap above the water surface whilst maintaining horizontal locomotion. This is done for various reasons. When travelling, jumping can save dolphins and porpoises energy as there is less friction while in the air. This type of travel is known as "porpoising". Other reasons for dolphins and porpoises performing porpoising include orientation, social displays, fighting, non-verbal communication, entertainment and attempting to dislodge parasites. In pinnipeds, two types of porpoising have been identified. "High porpoising" is most often near (within 100 m) the shore and is often followed by minor course changes; this may help seals get their bearings on beaching or rafting sites. "Low porpoising" is typically observed relatively far (more than 100 m) from shore and often aborted in favour of anti-predator movements; this may be a way for seals to maximize sub-surface vigilance and thereby reduce their vulnerability to sharks

Some whales raise their (entire) body vertically out of the water in a behaviour known as "breaching".

Birds

Some semi-aquatic birds use terrestrial locomotion, surface swimming, underwater swimming and flying (e.g., ducks, swans). Diving birds also use diving locomotion (e.g., dippers, auks). Some birds (e.g., ratites) have lost the primary locomotion of flight. The largest of these, ostriches, when being pursued by a predator, have been known to reach speeds over 70 km/h (43 mph), and can maintain a steady speed of 50 km/h (31 mph), which makes the ostrich the world's fastest two-legged animal. Ostriches can also locomote by swimming. Penguins either waddle on their feet or slide on their bellies across the snow, a movement called tobogganing, which conserves energy while moving quickly. They also jump with both feet together if they want to move more quickly or cross steep or rocky terrain. To get onto land, penguins sometimes propel themselves upwards at a great speed to leap out the water.

Changes during the life-cycle

An animal's mode of locomotion may change considerably during its life-cycle. Barnacles are exclusively marine and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters. They have two nektonic (active swimming) larval stages, but as adults, they are sessile (non-motile) suspension feeders. Frequently, adults are found attached to moving objects such as whales and ships, and are thereby transported (passive locomotion) around the oceans.

Function

Animals locomote for a variety of reasons, such as to find food, a mate, a suitable microhabitat, or to escape predators.

Food procurement

Animals use locomotion in a wide variety of ways to procure food. Terrestrial methods include ambush predation, social predation and grazing. Aquatic methods include filterfeeding, grazing, ram feeding, suction feeding, protrusion and pivot feeding. Other methods include parasitism and parasitoidism.

Quantifying body and limb movement

The study of animal locomotion is a branch of biology that investigates and quantifies how animals move. It is an application of kinematics, used to understand how the movements of animal limbs relate to the motion of the whole animal, for instance when walking or flying.