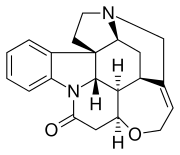

Dustjacket illustration of the first edition in both the UK and the US

| |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Alfred James Dewey |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | John Lane |

Publication date

| October 1920 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 296 (first edition, hardback) |

| Followed by | The Secret Adversary |

| Text | The Mysterious Affair at Styles at Wikisource |

The Mysterious Affair at Styles is a detective novel by British writer Agatha Christie. It was written in the middle of the First World War, in 1916, and first published by John Lane in the United States in October 1920 and in the United Kingdom by The Bodley Head (John Lane's UK company) on 21 January 1921.

Styles was Christie's first published novel. It introduced Hercule Poirot, Inspector (later, Chief Inspector) Japp, and Arthur Hastings. Poirot, a Belgian refugee of the Great War, is settling in England near the home of Emily Inglethorp, who helped him to his new life. His friend Hastings arrives as a guest at her home. When the woman is killed, Poirot uses his detective skills to solve the mystery.

The book includes maps of the house, the murder scene, and a drawing of a fragment of a will. The true first publication of the novel was as a weekly serial in The Times, including the maps of the house and other illustrations included in the book. This novel was one of the first ten books published by Penguin Books when it began in 1935.

This first mystery novel by Agatha Christie was well received by reviewers. An analysis in 1990 was positive about the plot, considered the novel one of the few by Christie that is well-anchored in time and place, a story that knows it describes the end of an era, and mentions that the plot is clever. Christie had not mastered cleverness in her first novel, as "too many clues tend to cancel each other out"; this was judged a difficulty "which Conan Doyle never satisfactorily overcame, but which Christie would."

Composition and original publication

Agatha Christie began working on The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1916, writing most of it on Dartmoor.

The character of Hercule Poirot was inspired by her experience working

as a nurse, ministering to Belgian soldiers during the First World War,

and by Belgian refugees who were living in Torquay.

The manuscript was rejected by Hodder and Stoughton and Methuen. Christie then submitted the manuscript to The Bodley Head. After keeping the submission for several months, The Bodley Head's founder, John Lane at The Bodley Head

offered to accept it, provided that Christie make slight changes to the

ending. She revised the next-to-last chapter, changing the scene of

Poirot's grand revelation from a courtroom to the Styles library. Christie later stated that the contract she signed with Lane was exploitative.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published by John Lane in the United States in October 1920 and by The Bodley Head in the United Kingdom on 21 January 1921. The US edition retailed at $2.00[1] and the UK edition at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6).

Plot summary

One morning at Styles Court, an Essex

country manor, its household wake to the discovery that the owner,

elderly Emily Inglethorp, has died. She had been poisoned with strychnine. Arthur Hastings, a soldier from the Western Front

staying there as a guest on his sick leave, ventures out to the nearby

village of Styles St. Mary, to enlist help from his friend staying there

- Hercule Poirot. Poirot learns that Emily was a woman of wealth - upon

the death of her previous husband, Mr. Cavendish, she inherited from

him both the manor

and a large portion of his income. Her household includes: her husband

Alfred Inglethorp, a younger man she recently married; her stepsons

(from her first husband's previous marriage) John and Lawrence

Cavendish; John's wife Mary Cavendish; Cynthia Murdoch, the daughter of a

deceased friend of the family; and Evelyn Howard, Emily's companion.

Poirot learns that per Emily's will, John is the vested remainderman

of the manor - he inherits the property from her, per his father's

will. However, the money she inherited would be distributed according to

her own will, which she changed at least once per year; her most recent

will favours Alfred, who will inherit her fortune.

On the day of the murder, Emily had been arguing with someone,

suspected to be either Alfred or John. She had been quite distressed

after this, and apparently made a new will - no one can find any

evidence that it exists. Alfred left the manor early that evening, and

stayed overnight in the village. Meanwhile, Emily ate little at dinner

and retired early to her room, taking her document case with her; when

her body was found, the case had been forced open and a document

removed. Nobody can explain how or when the poison was administered to

her.

Inspector Japp, the investigating officer, considers Alfred to be

the prime suspect, as he gains the most from his wife's death. The

Cavendishes suspect him to be a fortune hunter, as he was much younger

than Emily. Poirot notes his behaviour is suspicious during the

investigation - he refuses to provide an alibi,

and openly denies purchasing the strychnine in the village, despite

evidence to the contrary. Although Japp is keen to arrest him, Poirot

intervenes by proving he couldn't have purchased the poison; the

signature for the purchase is not in his handwriting. Suspicion now

falls on John - he is the next to gain from Emily's will, and has no

alibi for the murder. Japp soon arrests him - the signature for the

poison is in his handwriting; a phial that contained the poison is found

in his room; a beard and a pair of pince-nez identical to Alfred's, are found within the manor.

Poirot soon exonerates John of the crime. He reveals that the

murder was committed by Alfred Inglethorp, with aid from his cousin

Evelyn Howard. The pair pretended to be enemies, but were romantically

involved. They added bromide

to Emily's regular evening medicine, obtained from her sleeping powder,

which made the final dose lethal. The pair then left false evidence

that would incriminate Alfred, which they knew would be refuted at his

trial; once acquitted, he could not be tried for the crime again if

genuine evidence against him was found, per the law of double jeopardy.

John was framed by the pair as part of their plan; his handwriting was

forged by Evelyn, and the evidence against him was fabricated.

Poirot reveals that when he realised that Alfred wanted to be

arrested, he prevented Japp from doing so until he could discover why.

He also reveals that he found a letter in Emily's room, thanks to a

chance remark by Hastings, that detailed Alfred's intentions for his

wife. Emily's distress on the afternoon of the murder, was because she

had found it in his desk while searching for stamps. Her case was forced

open by Alfred, as he had discovered she had taken it; he was forced to

recover it from the case, and he hid it in the room, as he couldn't be

found with it.

Characters

- Hercule Poirot - Renowned Belgian private detective. He lives in England after being displaced by the war in Europe. Asked to investigate the case by his old friend Hastings.

- Hastings - Poirot's friend, and the narrator of the case. He is a guest at Styles Court while on sick leave from the Western Front.

- Inspector Japp - A Scotland Yard detective, and the investigating officer. He is an acquaintance of Poirot at the time of the novel's setting.

- Emily Inglethorp - A wealthy old woman, and the wife of Alfred Inglethorp. Her fortune and home of Styles Court were inherited by her following the death of her first husband, Mr Cavendish. The victim of the case.

- Alfred Inglethorp - Emily's second husband and a much younger man than her. Considered by her family to be a spoiled fortune-hunter. The killer of the case.

- John Cavendish - Emily's elder stepson, from her first husband's previous marriage, and the brother of Lawrence. The chief suspect after suspicion on Alfred is swayed away at Poirot's insistence.

- Mary Cavendish - John's wife, a friend of Dr Bauerstein.

- Lawrence Cavendish - Emily's younger stepson, from her first husband's previous marriage, and the brother of John. Known to have studied medicine.

- Evelyn Howard - Emily's companion, who is vocal about her negative views of Alfred Inglethorp.

- Cynthia Murdoch - The daughter of a deceased friend of the family, an orphan. She performs war-time work at a nearby hospital's pharmacy.

- Dr Bauerstein - A well-known toxicologist, living not far from Styles.

- Dorcas - A maid at Styles.

Dedication

The book's dedication reads: "To my Mother".

Christie's mother, Clarissa ("Clara") Boehmer Miller (1854–1926),

was a strong influence on her life and someone to whom Christie was

extremely close, especially after the death of her father in 1901. It

was while Christie was ill (circa 1908) that her mother suggested she

write a story. The result was The House of Beauty, now a lost work which hesitantly started her writing career. Christie later revised this story as The House of Dreams, and it was published in issue 74 of The Sovereign Magazine in January 1926 and, many years later, in 1997, in book form in While the Light Lasts and Other Stories.

Christie also dedicated her debut novel as Mary Westmacott, Giant's Bread (1930), to her mother who, by that time, had died.

Literary significance and reception

The Times Literary Supplement

(3 February 1921) gave the book an enthusiastic, if short, review,

which stated: "The only fault this story has is that it is almost too

ingenious." It went on to describe the basic set-up of the plot and

concluded: "It is said to be the author's first book, and the result of a

bet about the possibility of writing a detective story in which the

reader would not be able to spot the criminal. Every reader must admit

that the bet was won."

The New York Times Book Review (26 December 1920), was also impressed:

Though this may be the first published book of Miss Agatha Christie, she betrays the cunning of an old hand... You must wait for the last-but-one chapter in the book for the last link in the chain of evidence that enabled Mr. Poirot to unravel the whole complicated plot and lay the guilt where it really belonged. And you may safely make a wager with yourself that until you have heard M. Poirot's final word on the mysterious affair at Styles, you will be kept guessing at its solution and will most certainly never lay down this most entertaining book.

The novel's review in The Sunday Times

of 20 February 1921, quoted the publisher's promotional blurb

concerning Christie writing the book as the result of a bet that she

would not be able to do so without the reader being able to guess the

murderer, then said, "Personally we did not find the "spotting" so very

difficult, but we are free to admit that the story is, especially for a

first adventure in fiction, very well contrived, and that the solution

of the mystery is the result of logical deduction. The story, moreover,

has no lack of movement, and the several characters are well drawn."

The contributor who wrote his column under the pseudonym of "A

Man of Kent" in the 10 February 1921 issue of the Christian newspaper The British Weekly praised the novel but was overly generous in giving away the identity of the murderers. To wit,

It will rejoice the heart of all who truly relish detective stories, from Mr. McKenna downwards. I have heard that this is Miss Christie's first book, and that she wrote it in response to a challenge. If so, the feat was amazing, for the book is put together so deftly that I can remember no recent book of the kind, which approaches it in merit. It is well written, well proportioned, and full of surprises. When does the reader first suspect the murderer? For my part, I made up my mind from the beginning that the middle-aged husband of the old lady was in every way qualified to murder her, and I refused to surrender this conviction when suspicion of him is scattered for a moment. But I was not in the least degree prepared to find that his accomplice was the woman who pretended to be a friend. I ought to say, however, that an expert in detective stories with whom I discussed it, said he was convinced from the beginning that the true culprit was the woman whom the victim in her lifetime believed to be her staunchest friend. I hope I have not revealed too much of the plot. Lovers of good detective stories will, without exception, rejoice in this book.

The Bodley Head quoted excerpts from this review in future

books by Christie but, understandably, did not use those passages which

gave away the identity of the culprits.

"Introducing Hercule Poirot, the brilliant – and eccentric –

detective who, at a friend's request, steps out of retirement – and into

the shadows of a classic mystery on the outskirts of Essex. The victim

is the wealthy mistress of Styles Court, found in her locked bedroom

with the name of her late husband on her dying lips. Poirot has a few

questions for her fortune-hunting new spouse, her aimless stepsons, her

private doctor, and her hired companion. The answers are positively

poisonous. Who's responsible, and why, can only be revealed by the

master detective himself." (Book jacket, Berkley Book edition April

1984)

In his book, A Talent to Deceive – An Appreciation of Agatha Christie, Robert Barnard wrote:

Christie's debut novel, from which she made £25 and John Lane made goodness knows how much. The Big House in wartime, with privations, war work and rumours of spies. Her hand was over-liberal with clues and red herrings, but it was a highly cunning hand, even at this stage

In general The Mysterious Affair at Styles is a considerable achievement for a first-off author. The country-house-party murder is a stereotype in the detective-story genre, which Christie makes no great use of. Not her sort of occasion, at least later in life, and perhaps not really her class. The family party is much more in her line, and this is what we have here. This is one of the few Christies anchored in time and space: we are in Essex, during the First World War. The family is kept together under one roof by the exigencies of war and of a matriarch demanding rather than tyrannical – not one of her later splendid monsters, but a sympathetic and lightly shaded characterisation. If the lifestyle of the family still seems to us lavish, even wasteful, nevertheless we have the half sense that we are witnessing the beginning of the end of the Edwardian summer, that the era of country-house living has entered its final phase. Christie takes advantage of this end-of-an-era feeling in several ways: while she uses the full range of servants and their testimony, a sense of decline, of break-up is evident; feudal attitudes exist, but they crack easily. The marriage of the matriarch with a mysterious nobody is the central out-of-joint event in an intricate web of subtle changes. The family is lightly but effectively characterised, and on the outskirts of the story are the villagers, the small businessmen, and the surrounding farmers – the nucleus of Mayhem Parva. It is, too, a very clever story, with clues and red herrings falling thick and fast. We are entering the age when plans of the house were an indispensable aid to the aspirant solver of detective stories, and when cleverness was more important than suspense. But here we come to a problem that Agatha Christie has not yet solved, for cleverness over the long length easily becomes exhausting, and too many clues tend to cancel each other out, as far as reader interest is concerned. These were problems which Conan Doyle never satisfactorily overcame, but which Christie would.".

In the "Binge!" article of Entertainment Weekly Issue #1343-44 (26 December 2014–3 January 2015), the writers picked The Mysterious Affair at Styles as an "EW favorite" on the list of the "Nine Great Christie Novels".

Golden Age of Detective Fiction

The story is told in the first person by Hastings, and features many of the elements that have become icons of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction,

largely due to Christie's influence. It is set in a large, isolated

country manor. There are a half-dozen suspects, most of whom are hiding

facts about themselves. The plot includes a number of red herrings and surprise twists.

Impact on Christie's career

The Mysterious Affair at Styles launched Christie's writing career. Christie and her husband subsequently named their house "Styles".

Hercule Poirot, who first appeared in this novel, would go on to

become one of the most famous characters in detective fiction. Decades

later, when Christie told the story of Poirot's final case in Curtain, she set that novel at Styles.

Adaptations

Television

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was adapted as an episode for the series Agatha Christie's Poirot on 16 September 1990; the episode was specially made by ITV to celebrate the centenary of the author's birth. Filmed at Chavenage House, Gloucestershire,

the adaptation was generally faithful to the novel. However, it omitted

Dr Bauerstein and some minor characters, while it provided further

elaboration on Hastings' first meeting with Poirot - the pair met during

an investigation into a shooting, in which Hastings was a suspect.

Adaptor: Clive Exton

Director: Ross Devenish

Cast:

- David Suchet as Hercule Poirot

- Hugh Fraser as Lieutenant Arthur Hastings

- Philip Jackson as Inspector James Japp

- Gillian Barge as Emily Inglethorp

- Michael Cronin as Alfred Inglethorp

- David Rintoul as John Cavendish

- Anthony Calf as Lawrence Cavendish

- Beatie Edney as Mrs Mary Cavendish

- Joanna McCallum as Miss Evelyn Howard

- Allie Byrne as Miss Cynthia Murdoch

- Tim Munro as Edwin Mace

- Donald Pelmear as Judge

- Morris Perry as Wells

- Tim Preece as Phillips, KC

- David Savile as Superintendent Summerhaye

- Robert Vowles as Driver of Hired Car

- Michael D. Roberts as Tindermans

- Michael Godley as Dr Wilkins

- Penelope Beaumont as Mrs Raikes

- Lala Lloyd as Dorcas

- Bryan Coleman as a Vicar

Radio

The novel was adapted as a five-part serial for BBC Radio 4 in 2005. John Moffatt

reprised his role of Poirot. The serial was broadcast weekly from

Monday, 5 September to Monday, 3 October, from 11.30 am to 12.00 noon.

All five episodes were recorded on Monday, 4 April 2005, at Bush House. This version retained the first-person narration by the character of Hastings.

Adaptor: Michael Bakewell

Producer: Enyd Williams

Producer: Enyd Williams

Cast:

- John Moffatt as Hercule Poirot

- Simon Williams as Arthur Hastings

- Philip Jackson as Inspector James Japp

- Jill Balcon as Emily Inglethorp

- Hugh Dickson as Alfred Inglethorp

- Susan Jameson as Mary Cavendish

- Nicholas Boulton as Lawrence Cavendish

- Hilda Schroder as Dorcas

- Annabelle Dowler as Cynthia Murdoch and Annie

- Nichola McAuliffe as Evelyn Howard

- Sean Arnold as John Cavendish

- Richard Syms as Mr. Wells

- Ioan Meredith as Mr. Phillips

- Michael Mears as Sir Ernest Heavyweather

- Harry Myers as Mr. Mace

- Peter Howell as the Coroner

- Robert Portal as Dr Bauerstein

Stage

On 14 February 2012, Great Lakes Theater in Cleveland, Ohio debuted a 65-minute stage adaptation as part of their educational programming. Adapted by David Hansen, this production is performed by a cast of five (3 men, 2 women) with most performers playing more than one role.

On 17 March 2016, the Hedgerow Theatre

company in Media, Pennsylvania, premiered an adaptation by Jared Reed.

While largely faithful to the novel, the character of Inspector Japp was

omitted.

Publication history

- 1920, John Lane (New York), October 1920, Hardcover, 296 pp

- 1920, National Book Company, Hardcover, 296 pp

- 1921, John Lane (The Bodley Head), 21 January 1921, Hardcover, 296 pp

- 1926, John Lane (The Bodley Head), June 1926, Hardcover (Cheap edition – two shillings) 319 pp

- 1931, John Lane (The Bodley Head), February 1931 (As part of the Agatha Christie Omnibus along with The Murder on the Links and Poirot Investigates), Hardcover, Priced at seven shillings and sixpence; a cheaper edition at five shillings was published in October 1932

- 1932, John Lane (The Bodley Head), July 1932, Paperback (ninepence)

- 1935, Penguin Books, 30 July 1935, Paperback (sixpence), 255 pp

- 1945, Avon Books (New York), Avon number 75, Paperback, 226 pp

- 1954, Pan Books, Paperback (Pan number 310), 189 pp

- 1959, Pan Books, Paperback (Great Pan G112)

- 1961, Bantam Books (New York), Paperback, 154 pp

- 1965, Longman (London), Paperback, 181 pp

- 1976, Dodd, Mead and Company, (Commemorative Edition following Christie's death), Hardback, 239 pp; ISBN 0-396-07224-0

- 1984, Berkley Books (New York, Division of Penguin Putnam), Paperback, 198 pp; ISBN 0-425-12961-6

- 1988, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 208 pp; ISBN 0-00-617474-4

- 1989, Ulverscroft Large Print Edition, Hardcover; ISBN 0-7089-1955-3

- 2007, Facsimile of 1921 UK first edition (HarperCollins), 5 November 2007, Hardcover, 296 pp; ISBN 0-00-726513-1

- 2018, Srishti Publishers & Distributors, Paperback, 186 pp; ISBN 978-93-87022-25-6

Additional editions are listed at Fantastic Fiction, including

- 29 Hardcover editions from 1958 to September 2010 (ISBN 116928986X / 9781169289864 Publisher: Kessinger Publishing)

- 107 Paperback editions from 1970 to September 2013 (ISBN 0007527497 / 9780007527496 (UK edition) Publisher: Harper)

- 30 Audio editions from September 1994 to June 2013 (ISBN 1470887711 / 9781470887711 Publisher: Blackstone Audiobooks)

- 96 Kindle editions from December 2001 to November 2013 (ISBN B008BIGEHG).

The novel received its first true publication as an eighteen-part serialisation in The Times newspaper's Colonial Edition (aka The Weekly Times) from 27 February (Issue 2252) to 26 June 1920 (Issue 2269).

This version of the novel mirrored the published version with no

textual differences and included the maps and illustrations of

handwriting examples used in the novel. At the end of the serialisation

an advertisement appeared in the newspaper, which announced, "This is a

brilliant mystery novel, which has had the unique distinction for a

first novel of being serialised in The Times Weekly Edition. Mr. John Lane

is now preparing a large edition in volume form, which will be ready

immediately." Although another line of the advertisement stated that the

book would be ready in August, it was first published by John Lane in the United States in October 1920 and was not published in the UK by The Bodley Head until the following year.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles later made publishing history by being one of the first ten books to be published by Penguin Books when they were launched on 30 July 1935. The book was Penguin Number 6.

The blurb on the inside flap of the dustwrapper of the first edition reads:

This novel was originally written as the result of a bet, that the author, who had previously never written a book, could not compose a detective novel in which the reader would not be able to "spot" the murderer, although having access to the same clues as the detective. The author has certainly won her bet, and in addition to a most ingenious plot of the best detective type she has introduced a new type of detective in the shape of a Belgian. This novel has had the unique distinction for a first book of being accepted by the Times as a serial for its weekly edition.