Alaska Native dancers at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks Art Museum, 2006

Caddo members of the Caddo Cultural Club, Binger, Oklahoma, 2008

Native American writers Kim Shuck (Cherokee-Sac and Fox), Jewelle Gomez (Iowa), L. Frank (Tongva-Acjachemen) and Reid Gómez (Navajo)

Native American identity in the United States is an evolving topic based on the struggle to define "Native American"

or "(American) Indian" both for people who consider themselves Native

American and for people who do not. Some people seek an identity

that will provide for a stable definition for legal, social, and

personal purposes. There are a number of different factors which have

been used to define "Indianness," and the source and potential use of

the definition play a role in what definition is used. Facets which

characterize "Indianness" include culture, society, genes/biology, law, and self-identity.

An important question is whether the definition should be dynamic and

changeable across time and situation, or whether it is possible to

define "Indianness" in a static way.

The dynamic definitions may be based in how Indians adapt and adjust

to dominant society, which may be called an "oppositional process" by

which the boundaries between Indians and the dominant groups are

maintained. Another reason for dynamic definitions is the process of "ethnogenesis",

which is the process by which the ethnic identity of the group is

developed and renewed as social organizations and cultures evolve. The question of identity, especially aboriginal identity, is common in many societies worldwide.

The future of their identity is extremely important to Native Americans. Activist Russell Means

spoke frequently about the crumbling Indian way of life, the loss of

traditions, languages, and sacred places. He was concerned that there

may soon be no more Native Americans, only "Native American Americans,

like Polish Americans and Italian Americans."

As the number of Indians has grown (ten times as many today as in

1890), the number who carry on tribal traditions shrinks (one fifth as

many as in 1890), as has been common among many ethnic groups over time.

Means said, "We might speak our language, we might look like Indians

and sound like Indians, but we won’t be Indians."

Definitions

There

are various ways in which Indian identity has been defined. Some

definitions seek universal applicability, while others only seek

definitions for particular purposes, such as for tribal membership or

for the purposes of legal jurisdiction.

The individual seeks to have a personal identity that matches social

and legal definitions, although perhaps any definition will fail to

categorize correctly the identity of everyone.

American Indians were perhaps clearly identifiable at the turn of

the 20th century, but today the concept is contested. Malcolm

Margolin, co-editor of News From Native California muses, "I don’t know what an Indian is... [but] Some people are clearly Indian, and some are clearly not." Cherokee Chief (from 1985–1995) Wilma Mankiller

echoes: "An Indian is an Indian regardless of the degree of Indian

blood or which little government card they do or do not possess."

Further, it is difficult to know what might be meant by any Native American racial identity. Race is a disputed term, but is often said to be a social (or political) rather than biological construct. The issue of Native American racial identity was discussed by Steve Russell

(2002, p68), "American Indians have always had the theoretical option

of removing themselves from a tribal community and becoming legally

white. American law has made it easy for Indians to disappear because

that disappearance has always been necessary to the 'Manifest Destiny'

that the United States span the continent that was, after all,

occupied." Russell contrasts this with the reminder that Native

Americans are "members of communities before members of a race."

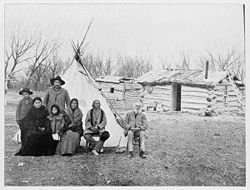

Traditional

Reservation

life has often been a blend of the traditional and the contemporary. In

1877, this Lakota family living at South Dakota's Rose Bud Agency had

both tipis and log cabins.

Traditional definitions of "Indianness" are also important. There is

a sense of "peoplehood" which links Indianness to sacred traditions,

places, and shared history as indigenous people. This definition transcends academic and legal terminology. Language is also seen as an important part of identity, and learning Native languages, especially for youth in a community, is an important part in tribal survival.

Some Indian artists find traditional definitions especially important. Crow poet Henry Real Bird

offers his own definition, "An Indian is one who offers tobacco to the

ground, feeds the water, and prays to the four winds in his own

language." Pulitzer Prize-winning Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday

gives a definition that is less spiritual but still based in the

traditions and experience of a person and their family, "An Indian is

someone who thinks of themselves as an Indian. But that's not so easy

to do and one has to earn the entitlement somehow. You have to have a

certain experience of the world in order to formulate this idea. I

consider myself an Indian; I've had the experience of an Indian. I know

how my father saw the world, and his father before him."

Constructed as an imagined community

Some

social scientists relate the uncertainty of Native American identity to

the theory of the constructed nature of identity. Many social

scientists discuss the construction of identity. Benedict Anderson's "imagined communities"

are an example. However, some see construction of identity as being

part of how a group remembers its past, tells its stories, and

interprets its myths. Thus cultural identity

is made within the discourses of history and culture. Identity thus

may not be a fact based in the essence of a person, but a positioning,

based in politics and social situations.

Blood quantum

A

common source of definition for an individual's being Indian is based

on their blood (ancestry) quantum (often one-fourth) or documented

Indian heritage. Almost two-thirds of all Indian federally recognized

Indian tribes in the United States require a certain blood quantum for

membership. Indian heritage is a requirement for membership in most American Indian Tribes. The Indian Reorganization Act

of 1934 used three criteria: tribal membership, ancestral descent, and

blood quantum (one half). This was very influential in using blood

quantum to restrict the definition of Indian. The use of blood quantum is seen by some as problematic as Indians marry out to other groups at a higher rate than any other United States ethnic or racial category. This could ultimately lead to their absorption into the rest of multiracial American society.

Residence on tribal lands

BIA map of reservations in the United States

Related to the remembrance and practice of traditions is the residence on tribal lands and Indian reservations.

Peroff (2002) emphasizes the role that proximity to other Native

Americans (and ultimately proximity to tribal lands) plays in one's

identity as a Native American.

Construction by others

Students at the Bismarck Indian School in the early twentieth century.

European conceptions of "Indianness" are notable both for how they

influence how American Indians see themselves and for how they have

persisted as stereotypes which may negatively affect treatment of

Indians. The noble savage stereotype is famous, but American colonists

held other stereotypes as well. For example, some colonists imagined

Indians as living in a state similar to their own ancestors, for example

the Picts, Gauls, and Britons before "Julius Caesar with his Roman legions (or some other) had ... laid the ground to make us tame and civil."

In the 19th and 20th century, particularly until John Collier's

tenure as Commissioner of Indian Affairs began in 1933, various

policies of the United States federal and state governments amounted to

an attack on Indian cultural identity and attempt to force assimilation.

These policies included but were not limited to the banning of

traditional religious ceremonies; forcing traditional hunter-gatherer

people to begin farming, often on land that was unsuitable and produced

few or no crops; forced cutting of hair; coercing "conversion" to Christianity by withholding rations; coercing Indian parents to send their children to boarding schools where the use of Native American languages was not permitted; freedom of speech restrictions; and restricted allowances of travel between reservations.

In the Southwest sections of the U.S. under Spanish control until

1810, where the majority (80%) of inhabitants were Indigenous, Spanish

government officials had similar policies.

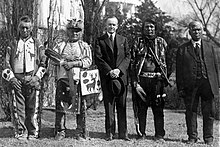

United States government definitions

President Coolidge stands with four Osage Indians at a White House ceremony

Some authors have pointed to a connection between social identity of

Native Americans and their political status as members of a tribe. There are 561 federally recognized tribal governments in the United States, which are recognized as having the right to establish their own legal requirements for membership.

In recent times, legislation related to Indians uses the "political"

definition of identifying as Indians those who are members of federally

recognized tribes. Most often given is the two-part definition: an

"Indian" is someone who is a member of an Indian tribe and an "Indian

tribe" is any tribe, band, nation, or organized Indian community

recognized by the United States.

The government and many tribes prefer this definition because it

allows the tribes to determine the meaning of "Indianness" in their own

membership criteria. However, some still criticize this saying that the

federal government's historic role in setting certain conditions on the

nature of membership criteria means that this definition does not

transcend federal government influence.

Thus in some sense, one has greater claim to a Native American

identity if one belongs to a federally recognized tribe, recognition

that many who claim Indian identity do not have.

Holly Reckord, an anthropologist who heads the BIA Branch of

Acknowledgment and Recognition, discusses the most common outcome for

those who seek membership: "We check and find that they haven't a trace

of Indian ancestry, yet they are still totally convinced that they are

Indians. Even if you have a trace of Indian blood, why do you want to

select that for your identity, and not your Irish or Italian? It's not

clear why, but at this point in time, a lot of people want to be

Indian.".

The Arts and Crafts Act

of 1990 attempts to take into account the limits of definitions based

in federally recognized tribal membership. In the act, having the

status of a state-recognized Indian tribe is discussed, as well as

having tribal recognition as an "Indian artisan" independent of tribal

membership. In certain circumstances, this allows people who identify

as Indian to legally label their products as "Indian made", even when

they are not members of a federally recognized tribe. In legislative hearings, one Indian artist, whose mother is not Indian but whose father is Seneca

and who was raised on a Seneca reservation, said, "I do not question

the rights of the tribes to set whatever criteria they want for

enrollment eligibility; but in my view, that is the extent of their

rights, to say who is an enrolled Seneca or Mohawk or Navajo or Cheyenne

or any other tribe. Since there are mixed bloods with enrollment

numbers and some of those with very small percentages of genetic Indian

ancestry, I don't feel they have the right to say to those of us without

enrollment numbers that we are not of Indian heritage, only that we are

not enrolled.... To say that I am not [Indian] and to prosecute me for

telling people of my Indian heritage is to deny me some of my civil liberties...and constitutes racial discrimination."

Some critics believe that using federal laws to define "Indian"

allows continued government control over Indians, even as the government

seeks to establish a sense of deference to tribal sovereignty. Critics

say Indianness becomes a rigid legal term defined by the BIA, rather

than an expression of tradition, history, and culture. For instance,

some groups which claim descendants from tribes that predate European

contact have not been able to achieve federal recognition. On the other

hand, Indian tribes have participated in setting policy with BIA as to

how tribes should be recognized. According to Rennard Strickland, an

Indian Law scholar, the federal government uses the process of

recognizing groups to "divide and conquer Indians: "the question of who

is 'more' or 'most' Indian may draw people away from common concerns."

Self-identification

In

some cases, one can self-identify about being Native American. For

example, one can often choose to identify as Indian without outside

verification when filling out a census form, a college application, or

writing a letter to the editor of a newspaper.

A "self-identified Indian" is a person who may not satisfy the legal

requirements which define a Native American according to the United

States government or a single tribe, but who understands and expresses

her own identity as Native American.

However, many people who do not satisfy tribal requirements identify

themselves as Native American, whether due to biology, culture, or some

other reason. The United States census

allows citizens to check any ethnicity without requirements of

validation. Thus, the census allows individuals to self-identify as

Native American, merely by checking the racial category, "Native

American/Alaska Native".

In 1990, about 60 percent of the more than 1.8 million persons

identifying themselves in the census as American Indian were actually

enrolled in a federally recognized tribe. Using self identification allows both uniformity and includes many different ideas of "Indianness". This is practiced by nearly half a million Americans who receive no benefits because

- they are not enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe, or

- they are full members of tribes which have never been recognized, or

- they are members of tribes whose recognition was terminated by the government during programs in the 1950s and 1960s.

Identity is in some way a personal issue; based on the way one feels

about oneself and one's experiences. Horse (2001) describes five

influences on self-identity as Indian:

- "The extent to which one is grounded in one’s Native American language and culture, one’s cultural identity";

- "The validity of one’s American Indian genealogy";

- "The extent to which one holds a traditional American Indian general philosophy or worldview (emphasizing balance and harmony and drawing on Indian spirituality)";

- "One’s self-concept as an American Indian"; and

- "One’s enrollment (or lack of it) in a tribe."

University of Kansas

sociologist Joane Nagel traces the tripling in the number of Americans

reporting American Indian as their race in the U.S. Census from 1960 to

1990 (from 523,591 to 1,878,285) to federal Indian policy, American

ethnic politics, and American Indian political activism. Much of the

population "growth" was due to "ethnic switching",

where people who previously marked one group, later mark another. This

is made possible by our increasing stress on ethnicity as a social

construct. In addition, since 2000 self-identification

in US censuses has allowed individuals to check multiple ethnic

categories, which is a factor in the increased American Indian

population since the 1990 census.

Yet, self-identification is problematic on many levels. It is sometimes

said, in fun, that the largest tribe in the United States may be the "Wantabes".

Garroutte identifies some practical problems with

self-identification as a policy, quoting the struggles of Indian service

providers who deal with many people who claim ancestors, some steps

removed, who were Indian. She quotes a social worker, "Hell, if all that

was real, there are more Cherokees in the world than there are Chinese."

She writes that in self-identification, privileging an individual's

claim over tribes' right to define citizenship can be a threat to tribal sovereignty.

Personal reasons for self-identification

Many

individuals seek broader definitions of Indian for personal reasons.

Some people whose careers involve the fact that they emphasize Native

American heritage and self-identify as Native American face difficulties

if their appearance, behavior, or tribal membership status does not

conform to legal and social definitions. Some have a longing for

recognition. Cynthia Hunt, who self-identifies as a member of the state-recognized Lumbee

tribe, says: "I feel as if I'm not a real Indian until I've got that

BIA stamp of approval .... You're told all your life that you're Indian,

but sometimes you want to be that kind of Indian that everybody else

accepts as Indian."

The importance that one "look Indian" can be greater than one's

biological or legal status. Native American Literature professor Becca

Gercken-Hawkins writes about the trouble of recognition for those who do

not look Indian; "I self-identify as Cherokee and Irish American,

and even though I do not look especially Indian with my dark curly hair

and light skin, I easily meet my tribe's blood quantum standards. My

family has been working for years to get the documentation that will

allow us to be enrolled members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Because of my appearance and my lack of enrollment status, I expect

questions regarding my identity, but even so, I was surprised when a

fellow graduate student advised me—in all seriousness—to straighten my hair

and work on a tan before any interviews. Thinking she was joking, I

asked if I should put a feather in my hair, and she replied with a

straight face that a feather might be a bit much, but I should at least

wear traditional Native jewelry."

Louis Owens,

an unenrolled author of Choctaw and Cherokee descent, discusses his

feelings about his status of not being a real Indian because he's not

enrolled. "I am not a real Indian. ... Because growing up in different

times, I naively thought that Indian was something we were, not

something we did or had or were required to prove on demand. Listening

to my mother's stories about Oklahoma, about brutally hard lives and dreams that cut across the fabric of every experience, I thought I was Indian."

Historic struggles

Florida State

anthropologist J. Anthony Paredes considers the question of Indianness

that may be asked about pre-ceramic peoples (what modern archaeologists

call the "Early" and "Middle Archaic" period), pre-maize burial mound cultures, etc. Paredes asks, "Would any [Mississippian high priest] have been any less awed than ourselves to come upon a so-called Paleo-Indian hunter hurling a spear at a woolly mastodon?" His question reflects the point that indigenous cultures are themselves the products of millennia of history and change.

The question of "Indianness" was different in colonial times.

Integration into Indian tribes was not difficult, as Indians typically

accepted persons based not on ethnic or racial characteristics, but on

learnable and acquirable designators such as "language, culturally

appropriate behavior, social affiliation, and loyalty." Non-Indian captives were often adopted into society, including, famously, Mary Jemison. As a side note, the "gauntlet"

was a ceremony that was often misunderstood as a form of torture, or

punishment but within Indian society was seen as a ritual way for the

captives to leave their European society and become a tribal member.

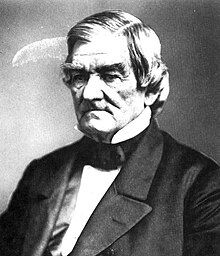

Cherokee chief John Ross

Since the mid-19th century, controversy and competition have worked

both within and outside tribes, as societies evolved. In the early

1860s, novelist John Rollin Ridge led a group of delegates to Washington D.C.

in an attempt to gain federal recognition for a "Southern Cherokee

Nation" which was a faction that was opposed to the leadership of rival

faction leader and Cherokee Chief John Ross.

In 1911, Arthur C. Parker, Carlos Montezuma, and others founded the Society of American Indians

as the first national association founded and run primarily by Native

Americans. The group campaigned for full citizenship for Indians, and

other reforms, goals similar to other groups and fraternal clubs, which

led to blurred distinctions between the different groups and their

members.

With different groups and people of different ethnicities involved in

parallel and often competing groups, accusations that one was not a real

Indian was a painful accusation for those involved. In 1918, Arapaho

Cleaver Warden testified in hearings related to Indian religious

ceremonies, "We only ask a fair and impartial trial by reasonable white

people, not half-breeds who do not know a bit of their ancestors or

kindred. A true Indian is one who helps for a race and not that

secretary of the Society of American Indians."

In the 1920s, a famous court case was set to investigate the ethnic identity of a woman known as "Princess Chinquilla" and her associate Red Fox James (aka Skiuhushu).

Chinquilla was a New York woman who claimed to have been separated from

her Cheyenne parents at birth. She and James created a fraternal club

which was to counter existing groups "founded by white people to help

the red race" in that it was founded by Indians. The club's opening

received much praise for supporting this purpose, and was seen as

authentic; it involved a Council Fire, the peace pipe, and speeches by Robert Ely, White Horse Eagle, and American Indian Defense Association

President Haven Emerson. In the 1920s, fraternal clubs were common in

New York, and titles such as "princess" and "chief" were bestowed by the

club to Natives and non-Natives. This allowed non-Natives to "try on" Indian identities.

Just as the struggle for recognition is not new, Indian

entrepreneurship based on that recognition is not new. An example is a

stipulation of the Creek Treaty of 1805 that gave Creeks the exclusive right to operate certain ferries and "houses of entertainment" along a federal road from Ocmulgee, Georgia to Mobile, Alabama, as the road went over parts of Creek Nation land purchased as an easement.

Unity and nationalism

1848 drawing of Tecumseh was based on a sketch done from life in 1808.

The issue of Indianness had somewhat expanded meaning in the 1960s with Indian nationalist movements such as the American Indian Movement.

The American Indian Movement unified nationalist identity was in

contrast to the "brotherhood of tribes" nationalism of groups like the National Indian Youth Council and the National Congress of American Indians. This unified Indian identity has been cited to the teachings of 19th century Shawnee leader Tecumseh to unify all Indians against "white oppression."

The movements of the 1960s changed dramatically how Indians see their

identity, both as separate from whites, as a member of a tribe, and as a

member of a unified category encompassing all Indians.

Examples

Different

tribes have unique cultures, histories, and situations that have made

particular the question of identity in each tribe. Tribal membership

may be based on descent, blood quantum, and/or reservation habitation.

Cherokee

Historically, race was not a factor in the acceptance of individuals into Cherokee society, since historically, the Cherokee people viewed their self-identity as a political rather than racial distinction. Going far back into the early colonial period, based upon existing social and historical evidence as well as oral history among the Cherokee themselves, the Cherokee society was best described as an Indian republic. Race and blood quantum are not factors in Cherokee Nation

tribal citizenship eligibility (like the majority of Oklahoma tribes).

To be considered a citizen in the Cherokee Nation, an individual needs a

direct Cherokee by blood or Cherokee freedmen ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls.

The tribe currently has members who also have African, Latino, Asian,

white and other ancestry, and an estimated 75 percent of tribal members

are less than one-quarter Indian by blood. The other two Cherokee tribes, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, do have a minimum blood quantum requirement. Numerous Cherokee heritage groups operate in the Southeastern U.S.

Theda Perdue (2000) recounts a story from "before the American

Revolution" where a black slave named Molly is accepted as a Cherokee as

a "replacement" for a woman who was beaten to death by her white

husband. According to Cherokee historical practices, vengeance for the

woman's death was required for her soul to find peace, and the husband

was able to prevent his own execution by fleeing to the town of Chota

(where according to Cherokee law he was safe) and purchasing Molly as

an exchange. When the wives family accepted Molly, later known as

"Chickaw," she became a part of their clan (the Deer Clan), and thus Cherokee.

Inheritance was largely matrilineal, and kinship and clan

membership was of primary importance until around 1810, when the seven Cherokee clans

began the abolition of blood vengeance by giving the sacred duty to the

new Cherokee National government. Clans formally relinquished judicial

responsibilities by the 1820s when the Cherokee Supreme Court was

established. When in 1825, the National Council extended citizenship to

biracial children of Cherokee men, the matrilineal definition of clans

was broken and clan membership no longer defined Cherokee citizenship.

These ideas were largely incorporated into the 1827 Cherokee

constitution.

The constitution did, state that "No person who is of negro or mulatlo

[sic]parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible

to hold any office of profit, honor or trust under this Government,"

with an exception for, "negroes and descendants of white and Indian men

by negro women who may have been set free."

Although by this time, some Cherokee considered clans to be

anachronistic, this feeling may have been more widely held among the

elite than the general population.

Thus even in the initial constitution, the Cherokee reserved the right

to define who was and was not Cherokee as a political rather than racial

distinction. Novelist John Rollin Ridge

led a group of delegates to Washington, D.C., as early as the 1860s in

an attempt to gain federal recognition for a "Southern Cherokee Nation"

which was a faction that was opposed to the leadership of rival faction

leader and Cherokee Chief John Ross.

Most of the 158,633 Navajos enumerated in the 1980 census and the 219,198 Navajos enumerated in the 1990 census were enrolled in the Navajo Nation,

which is the nation with the largest number of enrolled citizens. It

is notable as there is only a small number of people who identify as

Navajo who are not registered.

Lumbee

When the Lumbee of North Carolina

petitioned for recognition in 1974, many federally recognized tribes

adamantly opposed them. These tribes made no secret of their fear that

passage of the legislation would dilute services to historically

recognized tribes.

The Lumbee were at one point known by the state as the Cherokee tribe

of Robeson County and applied for federal benefits under that name in

the early 20th century. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

has been at the forefront of the opposition of the Lumbee. It is

sometimes noted that if granted full federal recognition, the

designation would bring tens of millions of dollars in federal benefits,

and also the chance to open a casino along Interstate 95 (which would

compete with a nearby Eastern Cherokee Nation casino).