From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

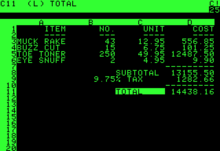

Example of a spreadsheet holding data about a group of audio tracks.

A spreadsheet is a computer application for computation, organization, analysis and storage of data in tabular form. Spreadsheets were developed as computerized analogs of paper accounting worksheets. The program operates on data entered in cells of a table. Each cell may contain either numeric or text data, or the results of formulas that automatically calculate and display a value based on the contents of other cells. The term spreadsheet may also refer to one such electronic document.

Spreadsheet users can adjust any stored value and observe the

effects on calculated values. This makes the spreadsheet useful for

"what-if" analysis since many cases can be rapidly investigated without

manual recalculation. Modern spreadsheet software can have multiple

interacting sheets and can display data either as text and numerals or

in graphical form.

Besides performing basic arithmetic and mathematical functions, modern spreadsheets provide built-in functions for common financial accountancy and statistical operations. Such calculations as net present value or standard deviation

can be applied to tabular data with a pre-programmed function in a

formula. Spreadsheet programs also provide conditional expressions,

functions to convert between text and numbers, and functions that

operate on strings of text.

Spreadsheets have replaced paper-based systems throughout the

business world. Although they were first developed for accounting or bookkeeping tasks, they now are used extensively in any context where tabular lists are built, sorted, and shared.

Basics

LANPAR, available in 1969,

was the first electronic spreadsheet on mainframe and time sharing

computers. LANPAR was an acronym: LANguage for Programming Arrays at

Random. VisiCalc (1979) was the first electronic spreadsheet on a microcomputer, and it helped turn the Apple II computer into a popular and widely used system. Lotus 1-2-3 was the leading spreadsheet when DOS was the dominant operating system. Microsoft Excel now has the largest market share on the Windows and Macintosh platforms. A spreadsheet program is a standard feature of an office productivity suite; since the advent of web apps, office suites now also exist in web app form.

A spreadsheet consists of a table of cells arranged into

rows and columns and referred to by the X and Y locations. X locations,

the columns, are normally represented by letters, "A," "B," "C," etc.,

while rows are normally represented by numbers, 1, 2, 3, etc. A single

cell can be referred to by addressing its row and column, "C10". This

electronic concept of cell references was first introduced in LANPAR

(Language for Programming Arrays at Random) (co-invented by Rene Pardo

and Remy Landau) and a variant used in VisiCalc and known as "A1

notation".

Additionally, spreadsheets have the concept of a range, a group

of cells, normally contiguous. For instance, one can refer to the first

ten cells in the first column with the range "A1:A10". LANPAR innovated

forward referencing/natural order calculation which didn't re-appear

until Lotus 123 and Microsoft's MultiPlan Version 2.

In modern spreadsheet applications, several spreadsheets, often known as worksheets or simply sheets, are gathered together to form a workbook.

A workbook is physically represented by a file containing all the data

for the book, the sheets, and the cells with the sheets. Worksheets are

normally represented by tabs that flip between pages, each one

containing one of the sheets, although Numbers

changes this model significantly. Cells in a multi-sheet book add the

sheet name to their reference, for instance, "Sheet 1!C10". Some systems

extend this syntax to allow cell references to different workbooks.

Users interact with sheets primarily through the cells. A given

cell can hold data by simply entering it in, or a formula, which is

normally created by preceding the text with an equals sign. Data might

include the string of text hello world, the number 5 or the date 16-Dec-91. A formula would begin with the equals sign, =5*3, but this would normally be invisible because the display shows the result of the calculation, 15 in this case, not the formula itself. This may lead to confusion in some cases.

The key feature of spreadsheets is the ability for a formula to

refer to the contents of other cells, which may, in turn, be the result

of a formula. To make such a formula, one replaces a number with a cell

reference. For instance, the formula =5*C10 would produce the result of multiplying the value in cell C10 by the number 5. If C10 holds the value 3 the result will be 15. But C10 might also hold its formula referring to other cells, and so on.

The ability to chain formulas together is what gives a

spreadsheet its power. Many problems can be broken down into a series of

individual mathematical steps, and these can be assigned to individual

formulas in cells. Some of these formulas can apply to ranges as well,

like the SUM function that adds up all the numbers within a range.

Spreadsheets share many principles and traits of databases,

but spreadsheets and databases are not the same things. A spreadsheet

is essentially just one table, whereas a database is a collection of

many tables with machine-readable

semantic relationships. While it is true that a workbook that contains

three sheets is indeed a file containing multiple tables that can

interact with each other, it lacks the relational structure of a database. Spreadsheets and databases are interoperable—sheets can be imported into databases to become tables within them, and database queries can be exported into spreadsheets for further analysis.

A spreadsheet program is one of the main components of an office productivity suite, which usually also contains a word processor, a presentation program, and a database

management system. Programs within a suite use similar commands for

similar functions. Usually, sharing data between the components is

easier than with a non-integrated collection of functionally equivalent

programs. This was particularly an advantage at a time when many

personal computer systems used text-mode displays and commands instead

of a graphical user interface.

History

Paper spreadsheets

The

word "spreadsheet" came from "spread" in its sense of a newspaper or

magazine item (text or graphics) that covers two facing pages, extending

across the centerfold and treating the two pages as one large page. The

compound word 'spread-sheet' came to mean the format used to present

book-keeping ledgers—with

columns for categories of expenditures across the top, invoices listed

down the left margin, and the amount of each payment in the cell where

its row and column intersect—which were, traditionally, a "spread"

across facing pages of a bound ledger (book for keeping accounting

records) or on oversized sheets of paper (termed 'analysis paper') ruled

into rows and columns in that format and approximately twice as wide as

ordinary paper.

Early implementations

Batch spreadsheet report generator BSRG

A batch "spreadsheet" is indistinguishable from a batch compiler with added input data, producing an output report, i.e., a 4GL

or conventional, non-interactive, batch computer program. However, this

concept of an electronic spreadsheet was outlined in the 1961 paper

"Budgeting Models and System Simulation" by Richard Mattessich. The subsequent work by Mattessich (1964a, Chpt. 9, Accounting and Analytical Methods) and its companion volume, Mattessich (1964b, Simulation of the Firm through a Budget Computer Program) applied computerized spreadsheets to accounting and budgeting systems (on mainframe computers programmed in FORTRAN IV).

These batch Spreadsheets dealt primarily with the addition or

subtraction of entire columns or rows (of input variables), rather than

individual cells.

In 1962, this concept of the spreadsheet, called BCL for Business Computer Language, was implemented on an IBM 1130 and in 1963 was ported to an IBM 7040 by R. Brian Walsh at Marquette University, Wisconsin. This program was written in Fortran. Primitive timesharing was available on those machines. In 1968 BCL was ported by Walsh to the IBM 360/67 timesharing machine at Washington State University. It was used to assist in the teaching of finance to business students. Students were able to take information prepared by the professor and manipulate it to represent it and show ratios etc. In 1964, a book entitled Business Computer Language was written by Kimball, Stoffells and Walsh and both the book and program were copyrighted in 1966 and years later that copyright was renewed.

Applied Data Resources had a FORTRAN preprocessor called Empires.

In the late 1960s, Xerox used BCL to develop a more sophisticated version for their timesharing system.

LANPAR spreadsheet compiler

A key invention in the development of electronic spreadsheets was made by Rene K. Pardo and Remy Landau, who filed in 1970 U.S. Patent 4,398,249 on a spreadsheet automatic natural order calculation algorithm.

While the patent was initially rejected by the patent office as being a

purely mathematical invention, following 12 years of appeals, Pardo and

Landau won a landmark court case at the Predecessor Court of the

Federal Circuit (CCPA), overturning the Patent Office in 1983 —

establishing that "something does not cease to become patentable merely

because the point of novelty is in an algorithm." However, in 1995 the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled the patent unenforceable.

The actual software was called LANPAR — LANguage for Programming Arrays at Random.

This was conceived and entirely developed in the summer of 1969,

following Pardo and Landau's recent graduation from Harvard University.

Co-inventor Rene Pardo recalls that he felt that one manager at Bell

Canada should not have to depend on programmers to program and modify

budgeting forms, and he thought of letting users type out forms in any

order and having an electronic computer calculate results in the right

order ("Forward Referencing/Natural Order Calculation"). Pardo and

Landau developed and implemented the software in 1969.

LANPAR was used by Bell Canada, AT&T, and the 18 operating

telephone companies nationwide for their local and national budgeting

operations. LANPAR was also used by General Motors. Its uniqueness was

Pardo's co-invention incorporating forward referencing/natural order

calculation (one of the first "non-procedural" computer languages) as opposed to left-to-right, top to bottom sequence for calculating the results in each cell that was used by VisiCalc, SuperCalc, and the first version of MultiPlan.

Without forward referencing/natural order calculation, the user had to

refresh the spreadsheet until the values in all cells remained

unchanged. Once the cell values stayed constant, the user was assured

that there were no remaining forward references within the spreadsheet.

Autoplan/Autotab spreadsheet programming language

In 1968, three former employees from the General Electric computer company headquartered in Phoenix, Arizona set out to start their own software development house.

A. Leroy Ellison, Harry N. Cantrell, and Russell E. Edwards found

themselves doing a large number of calculations when making tables for

the business plans that they were presenting to venture capitalists.

They decided to save themselves a lot of effort and wrote a computer

program that produced their tables for them. This program, originally

conceived as a simple utility for their personal use, would turn out to

be the first software product offered by the company that would become

known as Capex Corporation. "AutoPlan" ran on GE's Time-sharing service; afterward, a version that ran on IBM mainframes was introduced under the name AutoTab. (National CSS

offered a similar product, CSSTAB, which had a moderate timesharing

user base by the early 1970s. A major application was opinion research

tabulation.)

AutoPlan/AutoTab was not a WYSIWYG interactive

spreadsheet program, it was a simple scripting language for

spreadsheets. The user-defined the names and labels for the rows and

columns, then the formulas that defined each row or column. In 1975,

Autotab-II was advertised as extending the original to a maximum of "1,500 rows and columns, combined in any proportion the user requires..."

GE Information Services, which operated the time-sharing service,

also launched its own spreadsheet system, Financial Analysis Language

(FAL), circa 1974. It was later supplemented by an additional

spreadsheet language, TABOL,

which was developed by an independent author, Oliver Vellacott in the

UK. Both FAL and TABOL were integrated with GEIS's database system,

DMS.

IBM Financial Planning and Control System

The IBM Financial Planning and Control System was developed in 1976, by Brian Ingham at IBM Canada. It was implemented by IBM in at least 30 countries. It ran on an IBM mainframe and was among the first applications for financial planning developed with APL that completely hid the programming language from the end-user. Through IBM's VM operating system, it was among the first programs to auto-update each copy of the application

as new versions were released. Users could specify simple mathematical

relationships between rows and between columns. Compared to any

contemporary alternatives, it could support very large spreadsheets. It

loaded actual financial planning data

drawn from the legacy batch system into each user's spreadsheet

monthly. It was designed to optimize the power of APL through object

kernels, increasing program efficiency by as much as 50 fold over

traditional programming approaches.

APLDOT modeling language

An example of an early "industrial weight" spreadsheet was APLDOT, developed in 1976 at the United States Railway Association on an IBM 360/91, running at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, MD.

The application was used successfully for many years in developing such

applications as financial and costing models for the US Congress and

for Conrail.

APLDOT was dubbed a "spreadsheet" because financial analysts and

strategic planners used it to solve the same problems they addressed

with paper spreadsheet pads.

VisiCalc

VisiCalc running on an Apple II

Because Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston implemented VisiCalc on the Apple II in 1979 and the IBM PC

in 1981, the spreadsheet concept became widely known in the early

1980s. VisiCalc was the first spreadsheet that combined all essential

features of modern spreadsheet applications (except for forward

referencing/natural order recalculation), such as WYSIWYG

interactive user interface, automatic recalculation, status and formula

lines, range copying with relative and absolute references, formula

building by selecting referenced cells. Unaware of LANPAR at the time PC World magazine called VisiCalc the first electronic spreadsheet.

Bricklin has spoken of watching his university professor create a table of calculation results on a blackboard.

When the professor found an error, he had to tediously erase and

rewrite several sequential entries in the table, triggering Bricklin to

think that he could replicate the process on a computer, using the

blackboard as the model to view results of underlying formulas. His idea

became VisiCalc, the first application that turned the personal computer from a hobby for computer enthusiasts into a business tool.

VisiCalc went on to become the first "killer application",

an application that was so compelling, people would buy a particular

computer just to use it. VisiCalc was in no small part responsible for

the Apple II's success. The program was later ported to a number of other early computers, notably CP/M machines, the Atari 8-bit family and various Commodore platforms. Nevertheless, VisiCalc remains best known as an Apple II program.

SuperCalc

SuperCalc

was a spreadsheet application published by Sorcim in 1980, and

originally bundled (along with WordStar) as part of the CP/M software

package included with the Osborne 1 portable computer. It quickly became

the de facto standard spreadsheet for CP/M and was ported to MS-DOS in

1982.

Lotus 1-2-3 and other MS-DOS spreadsheets

The acceptance of the IBM PC

following its introduction in August 1981, began slowly because most of

the programs available for it were translations from other computer

models. Things changed dramatically with the introduction of Lotus 1-2-3

in November 1982, and release for sale in January 1983. Since it was

written especially for the IBM PC, it had a good performance and became

the killer app for this PC. Lotus 1-2-3 drove sales of the PC due to the

improvements in speed and graphics compared to VisiCalc on the Apple

II.

Lotus 1-2-3, along with its competitor Borland Quattro, soon displaced VisiCalc. Lotus 1-2-3 was released on January 26, 1983, started outselling then-most-popular VisiCalc the very same year, and for several years was the leading spreadsheet for DOS.

Microsoft Excel

Microsoft released the first version of Excel for the Macintosh on September 30, 1985, and then ported

it to Windows, with the first version being numbered 2.05 (to

synchronize with the Macintosh version 2.2) and released in November

1987. The Windows 3.x platforms of the early 1990s made it possible for

Excel to take market share from Lotus. By the time Lotus responded with

usable Windows products, Microsoft had begun to assemble their Office suite. By 1995, Excel was the market leader, edging out Lotus 1-2-3, and in 2013, IBM discontinued Lotus 1-2-3 altogether.

Web-based spreadsheets

Notable current web-based spreadsheet software:

Mainframe spreadsheets

- The Works Records System at ICI developed in 1974 on IBM 370/145

- ExecuCalc, from Parallax Systems, Inc.: Released in late 1982,

ExecuCalc was the first mainframe "visi-clone" which duplicated the

features of VisiCalc on IBM mainframes with 3270 display terminals. Over

150 copies were licensed (35 to Fortune 500 companies). DP managers

were attracted to compatibility and avoiding then-expensive PC purchases

(see 1983 Computerworld magazine front page article and advertisement.)

Other spreadsheets

Notable current spreadsheet software:

Discontinued spreadsheet software:

Other products

Several

companies have attempted to break into the spreadsheet market with

programs based on very different paradigms. Lotus introduced what is

likely the most successful example, Lotus Improv, which saw some commercial success, notably in the financial world where its powerful data mining capabilities remain well respected to this day.

Spreadsheet 2000 attempted to dramatically simplify formula construction, but was generally not successful.

Concepts

The main concepts are those of a grid of cells,

called a sheet, with either raw data, called values, or formulas in the

cells. Formulas say how to mechanically compute new values from

existing values. Values are general numbers, but can also be pure text,

dates, months, etc. Extensions of these concepts include logical

spreadsheets. Various tools for programming sheets, visualizing data,

remotely connecting sheets, displaying cells' dependencies, etc. are

commonly provided.

Cells

A "cell" can be thought of as a box for holding data.

A single cell is usually referenced by its column and row (C2 would

represent the cell containing the value 30 in the example table below).

Usually rows, representing the dependent variables, are referenced in decimal notation starting from 1, while columns representing the independent variables use 26-adic bijective numeration

using the letters A-Z as numerals. Its physical size can usually be

tailored to its content by dragging its height or width at box

intersections (or for entire columns or rows by dragging the column- or

row-headers).

My Spreadsheet

|

A |

B |

C |

D

|

| 01

|

Sales |

100000 |

30000 |

70000

|

| 02

|

Purchases |

25490 |

30 |

200

|

An array of cells is called a sheet or worksheet. It is analogous to an array of variables in a conventional computer program (although certain unchanging values, once entered, could be considered, by the same analogy, constants).

In most implementations, many worksheets may be located within a single

spreadsheet. A worksheet is simply a subset of the spreadsheet divided

for the sake of clarity. Functionally, the spreadsheet operates as a

whole and all cells operate as global variables within the spreadsheet (each variable having 'read' access only except its containing cell).

A cell may contain a value or a formula, or it may simply be left empty.

By convention, formulas usually begin with = sign.

Values

A value

can be entered from the computer keyboard by directly typing into the

cell itself. Alternatively, a value can be based on a formula (see

below), which might perform a calculation, display the current date or

time, or retrieve external data such as a stock quote or a database

value.

The Spreadsheet Value Rule

Computer scientist Alan Kay used the term value rule to summarize a spreadsheet's operation: a cell's value relies solely on the formula the user has typed into the cell.

The formula may rely on the value of other cells, but those cells are

likewise restricted to user-entered data or formulas. There are no 'side

effects' to calculating a formula: the only output is to display the

calculated result inside its occupying cell. There is no natural

mechanism for permanently modifying the contents of a cell unless the

user manually modifies the cell's contents. In the context of

programming languages, this yields a limited form of first-order functional programming.

Automatic recalculation

A

standard of spreadsheets since the 1980s, this optional feature

eliminates the need to manually request the spreadsheet program to

recalculate values (nowadays typically the default option unless

specifically 'switched off' for large spreadsheets, usually to improve

performance). Some earlier spreadsheets required a manual request to

recalculate since the recalculation of large or complex spreadsheets

often reduced data entry speed. Many modern spreadsheets still retain

this option.

Recalculation generally requires that there are no circular dependencies in a spreadsheet. A dependency graph

is a graph that has a vertex for each object to be updated, and an edge

connecting two objects whenever one of them needs to be updated earlier

than the other. Dependency graphs without circular dependencies form directed acyclic graphs, representations of partial orderings (in this case, across a spreadsheet) that can be relied upon to give a definite result.

Real-time update

This

feature refers to updating a cell's contents periodically with a value

from an external source—such as a cell in a "remote" spreadsheet. For

shared, Web-based spreadsheets, it applies to "immediately" updating

cells another user has updated. All dependent cells must be updated

also.

Locked cell

Once

entered, selected cells (or the entire spreadsheet) can optionally be

"locked" to prevent accidental overwriting. Typically this would apply

to cells containing formulas but might apply to cells containing

"constants" such as a kilogram/pounds conversion factor (2.20462262 to

eight decimal places). Even though individual cells are marked as

locked, the spreadsheet data are not protected until the feature is

activated in the file preferences.

Data format

A

cell or range can optionally be defined to specify how the value is

displayed. The default display format is usually set by its initial

content if not specifically previously set, so that for example

"31/12/2007" or "31 Dec 2007" would default to the cell format of date.

Similarly adding a % sign after a numeric value would tag the cell as a percentage cell format. The cell contents are not changed by this format, only the displayed value.

Some cell formats such as "numeric" or "currency" can also specify the number of decimal places.

This can allow invalid operations (such as doing multiplication

on a cell containing a date), resulting in illogical results without an

appropriate warning.

Cell formatting

Depending on the capability of the spreadsheet application, each cell (like its counterpart the "style" in a word processor) can be separately formatted using the attributes

of either the content (point size, color, bold or italic) or the cell

(border thickness, background shading, color). To aid the readability of

a spreadsheet, cell formatting may be conditionally applied to data;

for example, a negative number may be displayed in red.

A cell's formatting does not typically affect its content and

depending on how cells are referenced or copied to other worksheets or

applications, the formatting may not be carried with the content.

Named cells

Use of named column variables

x &

y in

Microsoft Excel. Formula for y=x

2 resembles

Fortran, and

Name Manager shows the definitions of

x &

y.

In most implementations, a cell, or group of cells in a column or

row, can be "named" enabling the user to refer to those cells by a name

rather than by a grid reference. Names must be unique within the

spreadsheet, but when using multiple sheets in a spreadsheet file, an

identically named cell range on each sheet can be used if it is

distinguished by adding the sheet name. One reason for this usage is for

creating or running macros that repeat a command across many sheets.

Another reason is that formulas with named variables are readily checked

against the algebra they are intended to implement (they resemble

Fortran expressions). The use of named variables and named functions

also makes the spreadsheet structure more transparent.

Cell reference

In

place of a named cell, an alternative approach is to use a cell (or

grid) reference. Most cell references indicate another cell in the same

spreadsheet, but a cell reference can also refer to a cell in a

different sheet within the same spreadsheet, or (depending on the

implementation) to a cell in another spreadsheet entirely, or a value

from a remote application.

A typical cell reference in "A1" style consists of one or

two case-insensitive letters to identify the column (if there are up to

256 columns: A–Z and AA–IV) followed by a row number (e.g., in the range

1–65536). Either part can be relative (it changes when the formula it

is in is moved or copied), or absolute (indicated with $ in front of the

part concerned of the cell reference). The alternative "R1C1" reference

style consists of the letter R, the row number, the letter C, and the

column number; relative row or column numbers are indicated by enclosing

the number in square brackets. Most current spreadsheets use the A1

style, some providing the R1C1 style as a compatibility option.

When the computer calculates a formula in one cell to update the

displayed value of that cell, cell reference(s) in that cell, naming

some other cell(s), causes the computer to fetch the value of the named

cell(s).

A cell on the same "sheet" is usually addressed as:

=A1

A cell on a different sheet of the same spreadsheet is usually addressed as:

=SHEET2!A1 (that is; the first cell in sheet 2 of the same spreadsheet).

Some spreadsheet implementations in Excel allow cell references to

another spreadsheet (not the currently open and active file) on the same

computer or a local network. It may also refer to a cell in another

open and active spreadsheet on the same computer or network that is

defined as shareable. These references contain the complete filename,

such as:

='C:\Documents and Settings\Username\My spreadsheets\[main sheet]Sheet1!A1

In a spreadsheet, references to cells automatically update when new

rows or columns are inserted or deleted. Care must be taken, however,

when adding a row immediately before a set of column totals to ensure

that the totals reflect the values of the additional rows—which they

often do not.

A circular reference

occurs when the formula in one cell refers—directly, or indirectly

through a chain of cell references—to another cell that refers back to

the first cell. Many common errors cause circular references. However,

some valid techniques use circular references. These techniques, after

many spreadsheet recalculations, (usually) converge on the correct

values for those cells.

Cell ranges

Likewise,

instead of using a named range of cells, a range reference can be used.

Reference to a range of cells is typical of the form (A1:A6), which

specifies all the cells in the range A1 through to A6. A formula such as

"=SUM(A1:A6)" would add all the cells specified and put the result in

the cell containing the formula itself.

Sheets

In the

earliest spreadsheets, cells were a simple two-dimensional grid. Over

time, the model has expanded to include a third dimension, and in some

cases a series of named grids, called sheets. The most advanced examples

allow inversion and rotation operations which can slice and project the

data set in various ways.

Formulas

Animation

of a simple spreadsheet that multiplies values in the left column by 2,

then sums the calculated values from the right column to the

bottom-most cell. In this example, only the values in the

A column are entered (10, 20, 30), and the remainder of cells are formulas. Formulas in the

B column multiply values from the A column using relative references, and the formula in

B4 uses the

SUM() function to find the

sum of values in the

B1:B3 range.

A formula identifies the calculation

needed to place the result in the cell it is contained within. A cell

containing a formula, therefore, has two display components; the formula

itself and the resulting value. The formula is normally only shown when

the cell is selected by "clicking" the mouse over a particular cell;

otherwise, it contains the result of the calculation.

A formula assigns values to a cell or range of cells, and typically has the format:

where the expression consists of:

- values, such as

2, 9.14 or 6.67E-11; - references to other cells, such as, e.g.,

A1 for a single cell or B1:B3 for a range; - arithmetic operators, such as

+, -, *, /, and others; - relational operators, such as

>=, <, and others; and, - functions, such as

SUM(), TAN(), and many others.

When a cell contains a formula, it often contains references to other

cells. Such a cell reference is a type of variable. Its value is the

value of the referenced cell or some derivation of it. If that cell in

turn references other cells, the value depends on the values of those.

References can be relative (e.g., A1, or B1:B3), absolute (e.g., $A$1, or $B$1:$B$3) or mixed row– or column-wise absolute/relative (e.g., $A1 is column-wise absolute and A$1 is row-wise absolute).

The available options for valid formulas depend on the particular

spreadsheet implementation but, in general, most arithmetic operations

and quite complex nested conditional operations can be performed by most

of today's commercial spreadsheets. Modern implementations also offer

functions to access custom-build functions, remote data, and

applications.

A formula may contain a condition (or nested conditions)—with or

without an actual calculation—and is sometimes used purely to identify

and highlight errors. In the example below, it is assumed the sum

of a column of percentages (A1 through A6) is tested for validity and

an explicit message put into the adjacent right-hand cell.

- =IF(SUM(A1:A6) > 100, "More than 100%", SUM(A1:A6))

Further examples:

- =IF(AND(A1<>"",B1<>""),A1/B1,"") means that if both

cells A1 and B1 are not <> empty "", then divide A1 by B1 and

display, other do not display anything.

- =IF(AND(A1<>"",B1<>""),IF(B1<>0,A1/B1,"Division by

zero"),"") means that if cells A1 and B1 are not empty, and B1 is not

zero, then divide A1 by B1, if B1 is zero, then display "Division by

zero", and do not display anything if either A1 and B1 are empty.

- =IF(OR(A1<>"",B1<>""),"Either A1 or B1 show text","")

means to display the text if either cells A1 or B1 are not empty.

The best way to build up conditional statements is step by step composing followed by trial and error testing and refining code.

A spreadsheet does not have to contain any formulas at all, in

which case it could be considered merely a collection of data arranged

in rows and columns (a database) like a calendar, timetable, or simple list. Because of its ease of use, formatting, and hyperlinking capabilities, many spreadsheets are used solely for this purpose.

Functions

Spreadsheets usually contain several supplied functions,

such as arithmetic operations (for example, summations, averages, and

so forth), trigonometric functions, statistical functions, and so forth.

In addition there is often a provision for user-defined functions. In Microsoft Excel, these functions are defined using Visual Basic for Applications

in the supplied Visual Basic editor, and such functions are

automatically accessible on the worksheet. Also, programs can be written

that pull information from the worksheet, perform some calculations,

and report the results back to the worksheet. In the figure, the name sq is user-assigned, and the function sq is introduced using the Visual Basic editor supplied with Excel. Name Manager displays the spreadsheet definitions of named variables x & y.

Subroutines

Functions themselves cannot write into the worksheet but simply return their evaluation. However, in Microsoft Excel, subroutines

can write values or text found within the subroutine directly to the

spreadsheet. The figure shows the Visual Basic code for a subroutine

that reads each member of the named column variable x, calculates its square, and writes this value into the corresponding element of named column variable y. The y

column contains no formula because its values are calculated in the

subroutine, not on the spreadsheet, and simply are written in.

Remote spreadsheet

Whenever

a reference is made to a cell or group of cells that are not located

within the current physical spreadsheet file, it is considered as

accessing a "remote" spreadsheet. The contents of the referenced cell

may be accessed either on the first reference with a manual update or

more recently in the case of web-based spreadsheets, as a near real-time

value with a specified automatic refresh interval.

Charts

Graph made using Microsoft Excel

Many spreadsheet applications permit charts and graphs (e.g., histograms, pie charts)

to be generated from specified groups of cells that are dynamically

re-built as cell contents change. The generated graphic component can

either be embedded within the current sheet or added as a separate

object. To create an Excel histogram, a formula based on the REPT

function can be used.

Multi-dimensional spreadsheets

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, first Javelin Software and Lotus Improv

appeared. Unlike models in a conventional spreadsheet, they utilized

models built on objects called variables, not on data in cells of a

report. These multi-dimensional spreadsheets enabled viewing data and algorithms

in various self-documenting ways, including simultaneous multiple

synchronized views. For example, users of Javelin could move through the

connections between variables on a diagram while seeing the logical

roots and branches of each variable. This is an example of what is

perhaps its primary contribution of the earlier Javelin—the concept of

traceability of a user's logic or model structure through its twelve

views. A complex model can be dissected and understood by others who had

no role in its creation.

In these programs, a time series,

or any variable, was an object in itself, not a collection of cells

that happen to appear in a row or column. Variables could have many

attributes, including complete awareness of their connections to all

other variables, data references, and text and image notes. Calculations

were performed on these objects, as opposed to a range of cells, so

adding two-time series automatically aligns them in calendar time, or in

a user-defined time frame. Data were independent of

worksheets—variables, and therefore data, could not be destroyed by

deleting a row, column, or entire worksheet. For instance, January's

costs are subtracted from January's revenues, regardless of where or

whether either appears in a worksheet. This permits actions later used

in pivot tables,

except that flexible manipulation of report tables, was but one of many

capabilities supported by variables. Moreover, if costs were entered by

week and revenues by month, the program could allocate or interpolate

as appropriate. This object design enabled variables and whole models to

reference each other with user-defined variable names and to perform

multidimensional analysis and massive, but easily editable

consolidations.

Trapeze, a spreadsheet on the Mac, went further and explicitly supported

not just table columns, but also matrix operators.

Logical spreadsheets

Spreadsheets that have a formula language based upon logical expressions, rather than arithmetic expressions are known as logical spreadsheets. Such spreadsheets can be used to reason deductively about their cell values.

Programming issues

Just

as the early programming languages were designed to generate

spreadsheet printouts, programming techniques themselves have evolved to

process tables (also known as spreadsheets or matrices) of data more efficiently in the computer itself.

End-user development

Spreadsheets are a popular end-user development tool.

EUD denotes activities or techniques in which people who are not

professional developers create automated behavior and complex data

objects without significant knowledge of a programming language. Many

people find it easier to perform calculations in spreadsheets than by

writing the equivalent sequential program. This is due to several traits

of spreadsheets.

- They use spatial relationships to define program relationships. Humans have highly developed intuitions

about spaces, and of dependencies between items. Sequential programming

usually requires typing line after line of text, which must be read

slowly and carefully to be understood and changed.

- They are forgiving, allowing partial results and functions to work.

One or more parts of a program can work correctly, even if other parts

are unfinished or broken. This makes writing and debugging programs

easier, and faster. Sequential programming usually needs every program

line and character to be correct for a program to run. One error usually

stops the whole program and prevents any result. Though this

user-friendliness is benefit of spreadsheet development, it often comes

with increased risk of errors.

- Modern spreadsheets allow for secondary notation.

The program can be annotated with colors, typefaces, lines, etc. to

provide visual cues about the meaning of elements in the program.

- Extensions that allow users to create new functions can provide the capabilities of a functional language.

- Extensions that allow users to build and apply models from the domain of machine learning.

- Spreadsheets are versatile. With their boolean logic and graphics capabilities, even electronic circuit design is possible.

- Spreadsheets can store relational data and spreadsheet formulas can express all queries of SQL. There exists a query translator, which automatically generates the spreadsheet implementation from the SQL code.

Spreadsheet programs

A "spreadsheet program"

is designed to perform general computation tasks using spatial

relationships rather than time as the primary organizing principle.

It is often convenient to think of a spreadsheet as a mathematical graph, where the nodes

are spreadsheet cells, and the edges are references to other cells

specified in formulas. This is often called the dependency graph of the

spreadsheet. References between cells can take advantage of spatial

concepts such as relative position and absolute position, as well as

named locations, to make the spreadsheet formulas easier to understand

and manage.

Spreadsheets usually attempt to automatically update cells when

the cells depend on change. The earliest spreadsheets used simple

tactics like evaluating cells in a particular order, but modern

spreadsheets calculate following a minimal recomputation order from the

dependency graph. Later spreadsheets also include a limited ability to

propagate values in reverse, altering source values so that a particular

answer is reached in a certain cell. Since spreadsheet cell formulas

are not generally invertible, though, this technique is of somewhat

limited value.

Many of the concepts common to sequential programming models have

analogs in the spreadsheet world. For example, the sequential model of

the indexed loop is usually represented as a table of cells, with similar formulas (normally differing only in which cells they reference).

Spreadsheets have evolved to use scripting programming languages like VBA as a tool for extensibility beyond what the spreadsheet language makes easy.

Shortcomings

While

spreadsheets represented a major step forward in quantitative modeling,

they have deficiencies. Their shortcomings include the perceived

unfriendliness of alpha-numeric cell addresses.

- Research by ClusterSeven has shown huge discrepancies in the way

financial institutions and corporate entities understand, manage and

police their often vast estates of spreadsheets and unstructured

financial data (including comma-separated values

(CSV) files and Microsoft Access databases). One study in early 2011 of

nearly 1,500 people in the UK found that 57% of spreadsheet users have

never received formal training on the spreadsheet package they use. 72%

said that no internal department checks their spreadsheets for accuracy.

Only 13% said that Internal Audit reviews their spreadsheets, while a

mere 1% receive checks from their risk department.

- Spreadsheets can have reliability problems. Research studies

estimate that around 1% of all formulas in operational spreadsheets are

in error.

- Despite the high error risks often associated with

spreadsheet authorship and use, specific steps can be taken to

significantly enhance control and reliability by structurally reducing

the likelihood of error occurrence at their source.

- The practical expressiveness of spreadsheets can be limited

unless their modern features are used. Several factors contribute to

this limitation. Implementing a complex model on a cell-at-a-time basis

requires tedious attention to detail. Authors have difficulty

remembering the meanings of hundreds or thousands of cell addresses that

appear in formulas.

- These drawbacks are mitigated by the use of named

variables for cell designations, and employing variables in formulas

rather than cell locations and cell-by-cell manipulations. Graphs can be

used to show instantly how results are changed by changes in parameter

values. The spreadsheet can be made invisible except for a transparent

user interface that requests pertinent input from the user, displays

results requested by the user, creates reports, and has built-in error

traps to prompt correct input.

- Similarly, formulas expressed in terms of cell addresses are

hard to keep straight and hard to audit. Research shows that spreadsheet

auditors who check numerical results and cell formulas find no more

errors than auditors who only check numerical results. That is another reason to use named variables and formulas employing named variables.

- Specifically, spreadsheets typically contain many copies

of the same formula. When the formula is modified, the user has to

change every cell containing that formula. In contrast, most computer

languages allow a formula to appear only once in the code and achieve

repetition using loops: making them much easier to implement and audit.

- The alteration of a dimension demands major surgery. When rows

(or columns) are added to or deleted from a table, one has to adjust the

size of many downstream tables that depend on the table being changed.

In the process, it is often necessary to move other cells around to make

room for the new columns or rows and to adjust graph data sources. In

large spreadsheets, this can be extremely time-consuming.

- Adding or removing a dimension is so difficult, one generally has to

start over. The spreadsheet as a paradigm forces one to decide on

dimensionality right of the beginning of one's spreadsheet creation,

even though it is often most natural to make these choices after one's

spreadsheet model has matured. The desire to add and remove dimensions

also arises in parametric and sensitivity analyses.

- Collaboration in authoring spreadsheet formulas can be difficult

when such collaboration occurs at the level of cells and cell addresses.

Other problems associated with spreadsheets include:

- Some sources advocate the use of specialized software instead of spreadsheets for some applications (budgeting, statistics)

- Many spreadsheet software products, such as Microsoft Excel (versions prior to 2007) and OpenOffice.org Calc (versions prior to 2008), have a capacity limit of 65,536 rows by 256 columns (216 and 28

respectively). This can present a problem for people using very large

datasets, and may result in data loss. In spite of the time passed, a

recent example is the loss of COVID-19 positives in the British statistics for September and October 2020.

- Lack of auditing and revision control.

This makes it difficult to determine who changed what and when. This

can cause problems with regulatory compliance. Lack of revision control

greatly increases the risk of errors due to the inability to track,

isolate and test changes made to a document.

- Lack of security.

Spreadsheets lack controls on who can see and modify particular data.

This, combined with the lack of auditing above, can make it easy for

someone to commit fraud.

- Because they are loosely structured, it is easy for someone to introduce an error,

either accidentally or intentionally, by entering information in the

wrong place or expressing dependencies among cells (such as in a

formula) incorrectly.

- The results of a formula (example "=A1*B1") applies only to a single

cell (that is, the cell the formula is located in—in this case perhaps

C1), even though it can "extract" data from many other cells, and even

real-time dates and actual times. This means that to cause a similar

calculation on an array of cells, an almost identical formula (but

residing in its own "output" cell) must be repeated for each row of the

"input" array. This differs from a "formula" in a conventional computer

program, which typically makes one calculation that it applies to all

the input in turn. With current spreadsheets, this forced repetition of

near-identical formulas can have detrimental consequences from a quality assurance standpoint and is often the cause of many spreadsheet errors. Some spreadsheets have array formulas to address this issue.

- Trying to manage the sheer volume of spreadsheets that may exist in

an organization without proper security, audit trails, the unintentional

introduction of errors, and other items listed above can become

overwhelming.

While there are built-in and third-party tools for desktop

spreadsheet applications that address some of these shortcomings,

awareness, and use of these is generally low. A good example of this is

that 55% of Capital market professionals "don't know" how their spreadsheets are audited; only 6% invest in a third-party solution.

Spreadsheet risk

Spreadsheet risk is the risk associated with deriving a materially

incorrect value from a spreadsheet application that will be utilized in

making a related (usually numerically based) decision. Examples include

the valuation of an asset, the determination of financial accounts, the calculation of medicinal doses, or the size of a load-bearing beam for structural engineering. The risk

may arise from inputting erroneous or fraudulent data values, from

mistakes (or incorrect changes) within the logic of the spreadsheet or

the omission of relevant updates (e.g., out of date exchange rates). Some single-instance errors have exceeded US$1 billion. Because spreadsheet risk is principally linked to the actions (or inaction) of individuals it is defined as a sub-category of operational risk.

Despite this, research carried out by ClusterSeven revealed that around half (48%) of c-level executives

and senior managers at firms reporting annual revenues over £50m said

there were either no usage controls at all or poorly applied manual

processes over the use of spreadsheets at the firms.

In 2013 Thomas Herndon, a graduate student of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst found major coding flaws in the spreadsheet used by the economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in Growth in a Time of Debt,

a very influential 2010 journal article. The Reinhart and Rogoff

article was widely used as justification to drive 2010–2013 European

austerity programs.