Research into food choice investigates how people select the food they eat. An interdisciplinary topic, food choice comprises psychological and sociological aspects (including food politics and phenomena such as vegetarianism or religious dietary laws),

economic issues (for instance, how food prices or marketing campaigns

influence choice) and sensory aspects (such as the study of the organoleptic qualities of food).

Factors that guide food choice include taste preference, sensory attributes, cost, availability, convenience, cognitive restraint, and cultural familiarity. In addition, environmental cues and increased portion sizes play a role in the choice and amount of foods consumed.

Food choice is the subject of research in nutrition, food science, psychology, anthropology, sociology, and other branches of the natural and social sciences. It is of practical interest to the food industry and especially its marketing endeavors. Social scientists have developed different conceptual frameworks of food choice behavior. Theoretical models of behavior incorporate both individual and environmental factors affecting the formation or modification of behaviors. Social cognitive theory examines the interaction of environmental, personal, and behavioral factors.

Factors that guide food choice include taste preference, sensory attributes, cost, availability, convenience, cognitive restraint, and cultural familiarity. In addition, environmental cues and increased portion sizes play a role in the choice and amount of foods consumed.

Food choice is the subject of research in nutrition, food science, psychology, anthropology, sociology, and other branches of the natural and social sciences. It is of practical interest to the food industry and especially its marketing endeavors. Social scientists have developed different conceptual frameworks of food choice behavior. Theoretical models of behavior incorporate both individual and environmental factors affecting the formation or modification of behaviors. Social cognitive theory examines the interaction of environmental, personal, and behavioral factors.

Taste preference

Researchers have found that consumers cite taste as the primary determinant of food choice.

Genetic differences in the ability to perceive bitter taste are

believed to play a role in the willingness to eat bitter-tasting

vegetables and in the preferences for sweet taste and fat content of

foods. Approximately 25 percent of the US population are supertasters and 50 percent are tasters. Epidemiological studies suggest that nontasters are more likely to eat a wider variety of foods and to have a higher body mass index (BMI), a measure of weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Environmental influences

Many environmental cues influence food choice and intake, although consumers may not be aware of their effects.

Examples of environmental influences include portion size, serving

aids, food variety, and ambient characteristics (discussed below).

Portion size

Portion sizes in the United States have increased markedly in the past several decades. For example, from 1977 to 1996, portion sizes increased by 60 percent for salty snacks and 52 percent for soft drinks. Importantly, larger product portion sizes and larger servings in restaurants and kitchens consistently increase food intake.

Larger portion sizes may even cause people to eat more of foods that

are ostensibly distasteful; in one study individuals ate significantly

more stale, two-week-old popcorn when it was served in a large versus a

medium-sized container.

Serving aids

Over 70 percent of one's total intake is consumed using serving aids such as plates, bowls, glasses, or utensils.

Consequently, serving aids can act as visual cues or cognitive

shortcuts that inform us of when to stop serving, eating, or drinking.

In one study, teenagers poured and consumed 74 percent more juice

into short, wide glasses compared to tall, narrow glasses of the same

volume. Similarly, veteran bartenders tend to pour 26 percent more liquor into short, wide glasses versus tall, narrow glasses.

This may be explained in part by Piaget's vertical-horizontal illusion,

in which people tend to focus on and overestimate an object's vertical

dimension at the expense of its horizontal dimension, even when the two

dimensions are identical in length.

In addition, larger bowls and spoons can also cause people to serve and consume a greater volume of food, although this effect may not also extend to larger plates. It has been suggested that people serve more food into larger dishes due to the Delboeuf illusion,

a phenomenon in which two identical circles are perceived to be

different in size depending upon the sizes of larger circles surrounding

them.

Plate color has also been shown to influence perception and

liking; in one study individuals perceived a dessert to be significantly

more likable, sweet, and intense when it was served on a white versus a

black plate.

Food variety

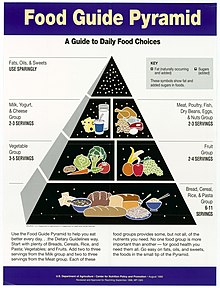

'The Food Guide Pyramid.

As a given food is increasingly consumed, the hedonic pleasantness of

the food's taste, smell, appearance, and texture declines, an effect

commonly referred to as sensory-specific satiety. Consequently, increasing the variety of foods available can increase overall food intake. This effect has been observed across both genders

and across multiple age groups, although there is some evidence that it

may be most pronounced in adolescence and diminished among older

adults.

Even the perceived variety of food can increase

consumption; individuals consumed more M&M candies when they came in

ten versus seven colors, despite identical taste. Furthermore, simply making a food assortment appear more disorganized versus organized can increase intake.

It has been suggested

that this variety effect may be evolutionarily adaptive, as complete

nutrition cannot be found in a single food, and increased dietary

variety increases the likelihood of meeting nutritional requirements for

various vitamins and minerals.

Ambient characteristics

Salience

Increased

food salience in one's environment (including both food visibility and

proximity) has been shown to increase consumption.

Regarding visibility, food is consumed at a faster rate or at a greater

volume when it is presented in clear versus opaque containers.

Having large stockpiles of food products at home can increase their

rate of consumption initially; however, after about a week's time the

consumption rate may drop back down to the level of non-stockpiled

foods, perhaps due to sensory-specific satiety.

Salient foods may increase intake by serving as a continuous

consumption reminder and increasing the number of food-related cognitive

choices an individual must make. Additionally, some studies have found that obese individuals may be

more susceptible to the influence of food salience and external cues

than individuals with a normal-weight BMI.

Distractions

Distractions

can increase food intake by initiating patterns of consumption,

obscuring ability to accurately monitor consumption, and extending meal

duration. For example, greater television viewing has been associated with increased meal frequency and caloric intake.

A study in Australian children found that those who watched two or more

hours of television per day were more likely to consume savory snacks

and less likely to consume fruit compared to those who watched less

television.

Other distractors such as reading, movie watching, and listening to the

radio have also been associated with increased consumption.

Temperature

Energy expenditure increases when ambient temperature is above or below the thermal neutral zone (the range of ambient temperature in which energy expenditure is not required for homeothermy).

It has been suggested that energy intake also increases during conditions of extreme or prolonged cold temperatures.

Relatedly, researchers have posited that reduced variability of ambient

temperature indoors could be a mechanism driving obesity, as the

percentage of US homes with air conditioning increased from 23 to 47

percent in recent decades. In addition, several human and animal

studies have shown that temperatures above the thermoneutral zone

significantly reduce food intake. However, overall there are few studies

indicating altered energy intake in response to extreme ambient

temperatures and the evidence is primarily anecdotal.

Lighting

There

is a dearth of research investigating relationships between lighting

and intake; however, extant literature suggests that harsh or glaring

lighting promotes eating faster,

whereas soft or warm lighting increases food intake by increasing

comfort level, lowering inhibition, and extending meal duration.

Music

Compared to

fast-tempo music, low-tempo music in a restaurant setting has been

associated with longer meal duration and greater consumption of both

food and drink, including alcoholic beverages.

Similarly, when individuals hear preferred versus non-preferred music

they tend to stay at dining establishments longer and spend more money

on food and drink.

Expert advice

In 2010, for the first time, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

(DGA) highlighted the role of the food environment in American food

choices and recommended changes in the food environment to support

individual behavior modification. The influence of environmental cues and other subtle factors have increased interest in using the principles of behavioral economics to change food behaviors.

Social influences

Presence and behavior of others

There

is a substantial amount of research indicating that the presence of

others influences food intake (discussed below). In reviewing this

literature, Herman, Roth, and Polivy have outlined three distinct effects:

1. Social facilitation – When eating in groups, people tend to eat more than they do when alone.

In daily diary studies, individuals have been found to eat from 30 to 40-50 percent

more while in the presence of others versus eating alone. In fact, some

research has indicated that the rate of intake is best described as a

linear function of the number of people present, such that meals eaten

with one, four, or seven other people were 33, 69, and 96 percent larger

than meals eaten alone, respectively. In addition to these observational findings, there is also experimental evidence for social facilitation effects.

Meal duration may be an important factor in social facilitation

effects; observational research has identified positive correlations

between group size and meal duration, and further investigation has confirmed meal duration as a mediator of group size-intake relationships.

2. Modeling – When eating in the presence of others who

consistently eat either a lot or a little, individuals tend to mirror

this behavior by also eating either a lot or a little.

Early studies of modeling effects investigated food intake alone

versus in the presence of others who either ate either a very small

amount (1 cracker) or a larger amount (20-40 crackers).

Findings were consistent, with individuals consuming more when paired

with a high-consumption companion than a low-consumption companion,

whereas eating alone was associated with an intermediate amount of

intake. Research manipulating eating social norms within real-life

actual friendships has also demonstrated modeling effects, as

individuals ate less in the company of friends who had been instructed

to restrict their intake versus those who had not been given these

instructions.

Furthermore, these modeling effects have been reported across a range

of diverse demographics, affecting both normal-weight and overweight

individuals, as well as both dieters and non-dieters.

Finally, regardless of whether individuals are very hungry or very

full, modeling effects remain very strong, suggesting that modeling may

trump signals of hunger or satiety sent from the gut.

3. Impression management

– When people eat in the presence of others who they perceive to be

observing or evaluating them, they tend to eat less than they would

otherwise eat alone.

Leary and Kowalski

define impression management in general as the process by which

individuals attempt to control the impressions others form of them.

Previous research has shown that certain types of eating companions make

people more or less eager to convey a good impression, and individuals

often attempt to achieve this goal by eating less. For example, people who are eating in the presence of unfamiliar others during a job interview or first date tend to eat less.

In a series of studies by Mori, Chaiken and Pliner, individuals

were given an opportunity to snack while getting acquainted with a

stranger.

In the first study, both males and females tended to eat less while in

the presence of an opposite-sex eating companion, and for females this

effect was most pronounced when the companion was most desirable. It

also seems that women may consume less in order to exude a feminine

identity; in a second study, women who were made to believe that a male

companion viewed them as masculine ate less than women who believed they

were perceived as feminine.

The weight of eating companions may also influence the volume of

food consumed. Obese individuals have been found to eat significantly

more in the presence of other obese individuals compared to

normal-weight others, while normal-weight individuals' eating appears

unaffected by the weight of eating companions.

4. Awareness Although the presence and behavior of others can

have a strong impact on eating behavior, many individuals are not aware

of these effects, and instead tend to attribute their eating behavior

primarily to other factors such as hunger and taste.

Relatedly, people tend to perceive factors like cost and health effects

as significantly more influential than social norms in determining

their own fruit and vegetable consumption.

Weight bias

Individuals who are overweight or obese may suffer from stigmatization or discrimination related to their weight, also called weightism or weight bias. There is emerging evidence that experiences with weight stigma may be a type of stereotype threat

which leads to behavior consistent with the stereotype; for example,

overweight and obese individuals ate more food after exposure to a

weight stigmatizing condition.

Additionally, in a study of over 2,400 overweight and obese women, 79

percent of women reported coping with weight stigma on multiple

occasions by eating more food.

Cognitive dietary restraint

Cognitive

dietary restraint refers to the condition where one is constantly

monitoring and attempting to restrict food intake in order to achieve or

maintain a desired body weight.

Strategies used by restrained eaters include choosing reduced-calorie

and reduced-fat foods, in addition to restricting overall caloric

intake. Individuals are classified as restrained eaters based on

responses to validated questionnaires such as the Three Factor Eating

Questionnaire and the restraint subscale of the Dutch Eating Behavior

Questionnaire. Recent research suggests that the combination of restraint and disinhibition

more accurately predict food choice than dietary restraint alone.

Disinhibition is another factor measured by the Three Factor Eating

Questionnaire. A positive score reflects a tendency towards overeating.

Individuals scoring high on the disinhibition subscale eat in response

to negative emotion, overeat when others are eating, and when in the

presence of tasty or comfort foods.

Gender differences

When

it comes to selecting food, women are more likely than men to choose

and consume foods based on health concerns or food contents. One possible explanation for this observed difference is women may be more concerned with body weight issues when choosing certain types of foods.

There may be an inverse relationship, as adolescent girls are noted to

have lower intakes of vitamins and minerals and ingest fewer

fruits/vegetables and dairy foods than adolescent boys.

Age differences

Across the lifespan, different eating habits can be observed based on

socio-economic status, workforce conditions, financial security, and

taste preference amongst other factors.

A significant portion of middle-aged and older adults responded to

choosing foods due to concerns with body-weight and heart disease,

whereas adolescents select food without consideration of the impact on

their health.

Convenience, appeal of food (taste and appearance), and hunger and food

cravings were found to be the greatest determinants of an adolescent’s

food choice.

Food choice can change from an early to mature age as a result of a

more sophisticated taste palate, income, and concerns about health and

wellness.

Socio-economic status

Income

and level of education influence food choice via the availability of

the resources to purchase a higher quality food and awareness of

nutritious alternatives. Diet may vary depending on the availability of income to purchase more healthier, nutrient-rich foods. For a low-income family, pricing plays a larger role than taste and quality in whether the food will be purchased. This may partly explain the lower life expectancy of lower-income groups. Similarly, higher levels of education equate to higher expectations from functional foods and avoidance of food additives.

Compared to conventional foods, organic foods have a higher cost and

people may have limited access if generating a low income. The variety

of foods carried in neighborhood stores may also influence diet ("food deserts").