From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tibetan_sovereignty_debate

The

Tibetan sovereignty debate refers to two

political debates. The first is whether the various territories within the

People's Republic of China (PRC) that are claimed as political

Tibet should

separate and become a new

sovereign state.

Many of the points in the debate rest on a second debate, about whether

Tibet was independent or subordinate to China in certain parts of its

recent history.

It is generally held that China and Tibet were independent prior to the

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and that Tibet has been ruled by the People's Republic of China (PRC) since 1959.

The nature of Tibet's relationship with China in the intervening period is a matter of debate:

- The PRC asserts that Tibet has been a part of China since the Mongol Yuan dynasty.

- The Republic of China (ROC) asserted that "Tibet was placed under the sovereignty of China" when the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) ended the brief Nepalese rule (1788-1792) from parts of Tibet in c. 1793.

- The Tibetan Government in Exile asserts that Tibet was an independent state until the PRC invaded Tibet in 1949/50.

- Some Western scholars maintain that Tibet and China were ruled by the Mongols during the Yuan dynasty, that Tibet was independent during the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644), and that Tibet was ruled by China or at the very least subordinate to the Manchu Qing during much of the Qing dynasty.

- Some Western scholars also maintain that Tibet was independent from c. 1912 to 1950, although it had extremely limited international recognition.

View of the Chinese governments

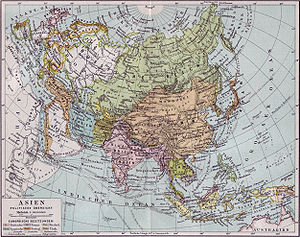

A 1734 Asia map, including China, Chinese Tartary, and Tibet, based on individual maps of the Jesuit fathers.

The UN map of the world in 1945, shows Tibet and Taiwan as part of the Republic of China. However, this presentation does not correspond to any opinion of the UN

In the late 19th century, China adopted the Western model of

nation-state diplomacy. As the government of Tibet, China concluded

several treaties (1876, 1886, 1890, 1893) with

British India touching on the status, boundaries and access to Tibet. Chinese government sources consider this a sign of

sovereignty rather than

suzerainty.

However, by the 20th century British India found the treaties to be

ineffective due to China's weakened control over the Tibetan local

government.

The British invaded Tibet in 1904 and forced the signing of a separate treaty, directly with the Tibetan government in Lhasa. In 1906, an

Anglo-Chinese Convention

was signed at Peking between Great Britain and China. It incorporated

the 1904 Lhasa Convention (with modification), which was attached as

Annex. A treaty between Britain and Russia (1907) followed.

Article II of this treaty stated that "In conformity with the admitted

principle of the suzerainty of China over Tibet, Great Britain and

Russia engage not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through

the intermediary of the Chinese Government." China sent troops into

Tibet in 1908. The result of the policy of both Great Britain and Russia

has been the virtual annexation of Tibet by China. China controlled Tibet up to 1912. Thereafter, Tibet entered the period described commonly as

de facto independence, though it was only recognized by independent Mongolia as enjoying

de jure independence.

In the 2000s the position of the Republic of China with regard to

Tibet appeared to become more nuanced as was stated in the following

opening speech to the International Symposium on Human Rights in Tibet

on 8

September 2007 through the pro-Taiwan independence then ROC President

Chen Shui-bian who stated that his offices no longer treated exiled Tibetans as Chinese mainlanders.

Legal arguments based on historical status

The

position of the People's Republic of China (PRC), which has ruled

mainland China since 1949, as well as the official position of the

Republic of China (ROC), which ruled mainland China before 1949 and

currently controls Taiwan, is that Tibet has been an indivisible part of China

de jure since the

Yuan dynasty of Mongol-ruled China in the 13th century, comparable to other states such as the

Kingdom of Dali and the

Tangut Empire that were also incorporated into China at the time.

The PRC contends that, according to

international law and the

Succession of states theory,

all subsequent Chinese governments have succeeded the Yuan Dynasty in

exercising de jure sovereignty over Tibet, with the PRC having succeeded

the ROC as the legitimate government of all China.

De facto independence

The ROC government had no effective control over Tibet from 1912 to 1951;

however, in the opinion of the Chinese government, this condition does

not represent Tibet's independence as many other parts of China also

enjoyed

de facto independence when the Chinese nation was torn by

warlordism,

Japanese invasion, and

civil war. Goldstein explains what is meant by

de facto independence in the following statement:

...[Britain] instead adopted a policy based on the idea of autonomy for Tibet within the context of Chinese suzerainty, that is to say, de facto independence for Tibet in the context of token subordination to China. Britain articulated this policy in the Simla Accord of 1914.

While at times the Tibetans were fiercely independent-minded at other

times Tibet indicated its willingness to accept subordinate status as

part of China

provided that Tibetan internal systems were left untouched and China

relinquished control over a number of important ethnic Tibetan groups in

Kham and

Amdo. The PRC insists that during this period the ROC government continued to maintain sovereignty over Tibet. The

Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China

(1912) stipulated that Tibet was a province of the Republic of China.

Provisions concerning Tibet in the Constitution of the Republic of China

promulgated later all stress the inseparability of Tibet from Chinese

territory, and the Central Government of China exercise of sovereignty

in Tibet. In 1927, the Commission in Charge of Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs of the Chinese Government contained members of great influence in the Mongolian and Tibetan areas, such as the 13th

Dalai Lama, the 9th

Panchen Lama and other Tibetan government representatives.

In 1934, on his condolence mission for the demise of the Dalai Lama,

the Chinese General Huang Musong posted notices in Chinese and Tibetan

throughout Lhasa that alluded to Tibet as an integral part of China

while expressing the utmost reverence for the Dalai Lama and the

Buddhist religion.

The

9th Panchen Lama traditionally ruled over one-third of Tibet. On 1

February 1925, the Panchen Lama attended the preparatory session of the "National Reconstruction Meeting" (

Shanhou huiyi)

intended to identify ways and means of unifying the Chinese nation, and

gave a speech about achieving the unification of five nationalities,

including Tibetans, Mongolians and Han Chinese. In 1933, he called upon

the Mongols to embrace national unity and to obey the Chinese Government

to resist Japanese invasion. In February 1935, the Chinese government

appointed Panchen Lama "Special Cultural Commissioner for the Western

Regions" and assigned him 500 Chinese troops.

He spent much of his time teaching and preaching Buddhist doctrines -

including the principles of unity and pacification for the border

regions - extensively in inland China, outside of Tibet, from 1924 until

1

December 1937, when he died on his way back to Tibet under the protection of Chinese troops.

The Kuomintang government sought to portray itself as necessary

to validate the choice of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. When the

current (14th) Dalai Lama was installed in Lhasa, it was with an armed

escort of Chinese troops and an attending Chinese minister The Muslim Kuomintang General

Bai Chongxi

said that the Tibetans suffered under British repression, and he called

upon the Republic of China to assist them in expelling the British. According to Yu Shiyu, during China's resistance war against Japanese invasion,

Chiang Kai-shek ordered the

Chinese Muslim General

Ma Bufang, Governor of

Qinghai (1937–1949), to repair the

Yushu airport in Qinghai Province to deter Tibetan independence.

In May 1943, Chiang warned that Tibet must accept and follow the

instructions and orders of the Central Government, that they must agree

and help to build the Chinese-India [war-supply] road, and that they

must maintain direct communications with the Office of the Mongolian and

Tibetan Affairs Commission (MTAC) in Lhasa and not through the newly

established "Foreign Office" of Tibet. He sternly warned that he would

"send an air force to bomb Tibet immediately" should Tibet be found to

be collaborating with Japan.

Official Communications between Lhasa and Chiang Kai-shek's government

was through MTAC, not the "Foreign Office", until July 1949 just before

the Communists' final victory in the civil war. The presence of MTAC in

Lhasa was viewed by both Nationalist and Communist governments as an

assertion of Chinese sovereignty over Tibet. Throughout the

Kuomintang years, no country gave Tibet

diplomatic recognition.

In 1950, after the People's Liberation Army entered Tibet, Indian leader

Jawaharlal Nehru

stated that his country would continue the British policy with regards

to Tibet in considering it to be outwardly part of China but internally

autonomous.

Foreign interventions

The

PRC considers all pro-independence movements aimed at ending Chinese

sovereignty in Tibet, including British attempts to establish control in

the late 19th century and early 20th century, the

CIA's backing of Tibetan insurgents during the 1950s and 1960s, and the

Government of Tibet in Exile till the turn of the 21st century, as one long campaign abetted by Western

imperialism aimed at destroying Chinese territorial integrity and sovereignty, or destabilizing China.

View of the Tibetan government and subsequent government in exile

Government of Tibet (1912–1951)

A proclamation issued by 13th Dalai Lama in 1913 states, "During the time of

Genghis Khan and

Altan Khan of the Mongols, the

Ming dynasty of the Chinese, and the

Qing Dynasty of the

Manchus, Tibet and China cooperated on the basis of benefactor and priest relationship. [...] the existing relationship between

Tibet and

China had been that of

patron and priest

and had not been based on the subordination of one to the other." He

condemned that the "Chinese authorities in Szechuan and Yunnan

endeavored to colonize our territory Chinese" in 1910–12 and stated that

"We are a small, religious, and independent nation".

Tibetan passports

The passport of Tsepon Shakabpa

In 2003, an old Tibetan

passport was rediscovered in Nepal. Issued by the

Kashag to Tibet's finance minister

Tsepon Shakabpa

for foreign travel, the passport was a single piece of pink paper,

complete with photograph. It has a message in hand-written Tibetan and

typed English, similar to the message by the nominal issuing officers of

today's passports, stating that ""

the bearer of this letter – Tsepon

Shakabpa, Chief of the Finance Department of the Government of Tibet,

is hereby sent to China, the United States of America, the United

Kingdom and other countries to explore and review trade possibilities

between these countries and Tibet. We shall, therefore, be grateful if

all the Governments concerned on his route would kindly give due

recognition as such, grant necessary passport, visa, etc. without any

hindrance and render assistance in all possible ways to him." The text and the photograph is sealed by a square stamp belonging to the Kashag, and is dated "

26th day of the 8th month of Fire-Pig year (Tibetan)" (14 October 1947 in the gregorian calendar).

The passport has received visas and entry stamps from several

countries and territories, including India, the United States, the

United Kingdom, France, Italy, Switzerland, Pakistan, Iraq and Hong

Kong, but not China. Some visa do reflect an official status, with

mentions such as "Diplomatic courtesy, Service visa, Official gratis,

Diplomatic visa, For government official".

However, acceptance of a passport does not indicate recognition of independence, as for example the

Republic of China passport is accepted by almost all the countries of the world, even though few of them recognize the ROC as a nation.

Tibet Government in exile (post 1959)

In 1959, the

14th Dalai Lama fled Tibet and established a

government in exile at

Dharamsala in northern

India. This group claims sovereignty over various ethnically or historically Tibetan areas now governed by China. Aside from the

Tibet Autonomous Region, an area that was administered directly by the Dalai Lama's government until 1951, the group also claims

Amdo (

Qinghai) and eastern

Kham (western

Sichuan).

About 45 percent of ethnic Tibetans under Chinese rule live in the

Tibet Autonomous Region, according to the 2000 census. Prior to 1949,

much of Amdo and eastern Kham were governed by local rulers and even

warlords.

The view of the current Dalai Lama in 1989 was as follows:

During the 5th Dalai Lama's time

[1617–1682], I think it was quite evident that we were a separate

sovereign nation with no problems. The 6th Dalai Lama [1683–1706] was

spiritually pre-eminent, but politically, he was weak and uninterested.

He could not follow the 5th Dalai Lama's path. This was a great failure.

So, then the Chinese influence increased. During this time, the

Tibetans showed quite a deal of respect to the Chinese. But even during

these times, the Tibetans never regarded Tibet as a part of China. All

the documents were very clear that China, Mongolia and Tibet were all

separate countries. Because the Chinese emperor was powerful and

influential, the small nations accepted the Chinese power or influence.

You cannot use the previous invasion as evidence that Tibet belongs to

China. In the Tibetan mind, regardless of who was in power, whether it

was the Manchus [the Qing dynasty], the Mongols [the Yuan dynasty] or

the Chinese, the east of Tibet was simply referred to as China. In the

Tibetan mind, India and China were treated the same; two separate

countries.

The

International Commission of Jurists

concluded that from 1913 to 1950 Tibet demonstrated the conditions of

statehood as generally accepted under international law. In the opinion

of the commission, the government of Tibet conducted its own domestic

and foreign affairs free from any outside authority, and countries with

whom Tibet had foreign relations are shown by official documents to have

treated Tibet in practice as an independent State.

The United Nations General Assembly passed resolutions urging respect for the rights of Tibetans in 1959, 1961, and 1965. The 1961 resolution calls for that "principle of self-determination of peoples and nations" applies to the Tibetan people.

The Tibetan Government in Exile views current PRC rule in Tibet,

including neighboring provinces outside Tibet Autonomous Region, as

colonial and illegitimate, motivated solely by the natural resources and

strategic value of Tibet, and in gross violation of both Tibet's

historical status as an independent country and the right of Tibetan

people to

self-determination. It also points to PRC's autocratic policies,

divide-and-rule policies, and what it contends are assimilationist policies, and regard those as an example of ongoing

imperialism

aimed at destroying Tibet's distinct ethnic makeup, culture, and

identity, thereby cementing it as an indivisible part of China.

That said, the Dalai Lama stated in 2008 that he wishes only for

Tibetan autonomy, and not separation from China, under certain

conditions, like freedom of speech and expression, genuine self-rule,

and control over ethnic makeup and migration in all areas claimed as

historical Tibet.

Third-party views

During the rule of the Chinese

Tang dynasty

(618–907), Tibet and China were frequently at war, with parts of Tibet

temporarily captured by the Chinese to become part of their territory. Around 650, the Chinese captured Lhasa. In 763, Tibet very briefly took the Chinese capital of

Chang'an during the Tang civil war.

Most scholars outside of China say that

during the

Ming dynasty

(1368–1644), Tibet was independent without even nominal Ming

suzerainty. In contrast, since the mid-18th century it is agreed that

China had control over Tibet reaching its maximum in the end of the 18th

century.

Luciano Petech, a scholar of Himalayan history, indicated that Tibet was a Qing protectorate.

The

patron and priest relationship

held between the Qing court and the Tibetan lamas has been subjected to

varying interpretation. The 13th Dalai Lama, for example, knelt, but

did not kowtow, before the

Empress Dowager Cixi

and the young Emperor while he delivered his petition in Beijing.

Chinese sources emphasize the submission of kneeling; Tibetan sources

emphasize the lack of the kowtow. Titles and commands given to Tibetans

by the Chinese, likewise, are variously interpreted. The Qing

authorities gave the 13th Dalai Lama the title of "Loyally Submissive

Vice-Regent", and ordered to follow Qing's commands and communicate with

the Emperor only through the Manchu Amban in

Lhasa;

but opinions vary as to whether these titles and commands reflected

actual political power, or symbolic gestures ignored by Tibetans. Some authors claim that kneeling before the Emperor followed the 17th-century precedent in the case of the

5th Dalai Lama. Other historians indicate that the emperor treated the Dalai Lama as an equal

Kneeling was a compromise allowed by the Qing court for foreign

representatives, Western and Tibetan alike, as both parties refused to

perform the kowtow.

Tibetologist Melvyn C. Goldstein writes that

Britain and

Russia formally acknowledged Chinese authority over Tibet in treaties of 1906 and 1907; and that the 1904

British invasion of Tibet stirred China into becoming more directly involved in Tibetan affairs and working to integrate Tibet with "the rest of China."

The status of Tibet after the 1911

Xinhai Revolution

ended the Qing dynasty is also a matter of debate. After the

revolution, the Chinese Republic of five races, including Tibetans, was

proclaimed. Western powers recognized the Chinese Republic, however the

13th Dalai Lama proclaimed Tibet's independence. Some authors indicate

that personal allegiance of the Dalai Lama to the Manchu Emperor came to

an end and no new type of allegiance of Tibet to China was established, or that Tibet had relationships with the empire and not with the new nation-state of China.

Barnett observes that there is no document before 1950 in which Tibet

explicitly recognizes Chinese sovereignty, and considers Tibet's

subordination to China during the periods when China had most authority

comparable to that of a colony.

Tibetologist Elliot Sperling noted that the Tibetan term for China,

Rgya-nag, did not mean anything more than a country bordering Tibet from

the east, and did not include Tibet. Other Tibetologists write that no country publicly accepts Tibet as an independent state, although there are several instances of government officials appealing to their superiors to do so. Treaties signed by Britain and Russia in the early years of the 20th century, and others signed by Nepal and India in the 1950s, recognized Tibet's political subordination to China. The United States presented a similar viewpoint in 1943. Goldstein also says that a 1943 British official letter "reconfirmed that Britain considered Tibet as part of China." Nevertheless, Goldstein views Tibet as occupied. Stating that The

Seventeen-Point Agreement was intended to facilitate the military

occupation of Tibet.

Thomas Heberer, professor of political science and East Asian

studies at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany, wrote: "No country

in the world has ever recognized the independence of Tibet or declared

that Tibet is an 'occupied country'. For all countries in the world,

Tibet is Chinese territory."

However, newly independent Mongolia and Tibet recognized each other by a

treaty signed just after the fall of the Qing dynasty, and under

international law, even non-recognition by other states does not negate

even a unilateral declaration of independence. During the early 1990s

governmental bodies, including the European Union and United States

Congress, and other international organisations declared that Tibetans

lacked the enjoyment of self-determination to which they are entitled and that it is an occupied territory.

Under the terms of the

Simla Accord (1914), the British Government's position was that China held

suzerainty over Tibet but not full sovereignty. By 2008, it was the only state still to hold this view.

David Miliband,

the British Foreign Secretary, described the old position as an

anachronism originating in the geopolitics of the early 20th century.

Britain revised this view on 29 October 2008, when it recognised

Chinese sovereignty over Tibet by issuing a statement on its website.

The Economist

reported at that time that although the British Foreign Office's

website did not use the word sovereignty, officials at the Foreign

Office said "it means that, as far as Britain is concerned, 'Tibet is

part of China. Full stop.'"

In 2008,

European Union leader José Manuel Barroso stated that the EU recognized Tibet as integral part of China: On 1 April 2009, the French Government reaffirmed its position on the Tibet issue.

In 2014, U.S. President

Barack Obama stated that "We recognize Tibet as part of the People's Republic of China. We are not in favor of independence."

This lack of legal recognition makes it difficult for

international legal experts sympathetic to the Tibetan Government in

Exile to argue that Tibet formally established its independence. On the other hand, in 1959 and 1960, the

International Commission of Jurists concluded that Tibet had been independent between 1913 and 1950.

Genocide allegations

Groups such as the Madrid-based

Committee to Support Tibet

claim the death toll in Tibet since the 1950 People's Liberation Army

invasion of Tibet to be 1,200,000 and have filed official charges of

genocide against prominent Chinese leaders and officials.

This figure has been disputed by Patrick French, a supporter of the

Tibetan cause who was able to view the data and calculations, but rather, concludes a no less devastating death toll of half a million people as a direct result of Chinese policies.

According to an ICJ (

International Commission of Jurists)

report released in 1960, there was no "sufficient proof of the

destruction of Tibetans as a race, nation or ethnic group as such by

methods that can be regarded as genocide in international law" found in

Tibet.

Other rights

Tibetologist Robert Barnett wrote about clerical resistance to

the introduction of anything Anti-Buddhist that might disturb the

prevailing power structure. Clergy obstructed modernization attempts by

the 13th Dalai Lama.

Old Tibet had a long history of persecuting non-Buddhist

Christians. In the years 1630 and 1742, Tibetan Christian communities

were suppressed by the lamas of the Gelugpa Sect, whose chief lama was

the Dalai Lama. Jesuit priests were made prisoners in 1630 or attacked

before they reached

Tsaparang.

Between 1850 and 1880, eleven fathers of the Paris Foreign Mission

Society were murdered in Tibet, or killed or injured during their

journeys to other missionary outposts in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands.

In 1881 Father Brieux was reported to have been murdered on his way to

Lhasa. Qing officials later discovered that the murder cases were in

fact covertly supported and even orchestrated by local lamaseries and

their patrons—the native chieftains. In 1904, Qing official Feng Quan

sought to curtail the influence of the Gelugpa Sect and ordered the

protection of Western missionaries and their churches. Indignation over

Feng Quan and the Christian presence escalated to a climax in March

1905, when thousands of the Batang lamas revolted, killing Feng, his

entourage, local Manchu and Han Chinese officials, and the local French

Catholic priests. The revolt soon spread to other cities in eastern

Tibet, such as Chamdo, Litang and Nyarong, and at one point almost

spilled over into neighboring Sichuan Province. The missionary stations

and churches in these areas were burned and destroyed by the angry

Gelugpa monks and local chieftains. Dozens of local Westerners,

including at least four priests, were killed or fatally wounded. The

scale of the rebellion was so tremendous that only when panicked Qing

authorities hurriedly sent 2,000 troops from Sichuan to pacify the mobs

did the revolt gradually come to an end. The lamasery authorities and

local native chieftains' hostility towards the Western missionaries in

Tibet lingered through the last throes of the Manchu dynasty and into

the Republican period.

Three UN resolutions of 1959, 1961, and 1965 condemned human

rights violation in Tibet. These resolutions were passed at a time when

the PRC was not

permitted to become a member

and of course was not allowed to present its singular version of events

in the region (however, the Republic of China on Taiwan, which the PRC

also tries to claim sovereignty over, was a member of the UN at the

time, and it equally claimed sovereignty over Tibet and opposed Tibetan

self-determination). Professor and sinologist

A. Tom Grunfeld called the resolutions impractical and justified the PRC in ignoring them.

Grunfeld questioned Human Rights Watch reports on human rights abuses in Tibet, saying they distorted the big picture.

According to Barnett, since Western powers and especially the

United States used the Tibet issue in the 1950s and 1960s for cold war

political purposes, the PRC is now able to get support from developing

countries in defeating the last nine attempts at the United Nations to

criticize China. Barnett writes that the position of the Chinese in

Tibet would be more accurately characterized as a colonial occupation,

and that such an approach might cause developing nations to be more

supportive of the Tibetan cause.

The Chinese government ignores the issue of its alleged

violations of Tibetan human rights, and prefers to argue that the

invasion was about territorial integrity and unity of the State. Furthermore, Tibetan activists inside Tibet have until recently focused on independence, not human rights.

Leaders of the

Tibetan Youth Congress which claims a strength of over 30,000 members are alleged by China to advocate violence. In 1998, Barnett wrote that

India's military includes 10,000 Tibetans, a fact that has been causing

China some unease. He further wrote that "at least seven bombs exploded

in Tibet between 1995 and 1997, one of them laid by a monk, and a

significant number of individual Tibetans are known to be actively

seeking the taking up of arms; hundreds of Chinese soldiers and police

have been beaten during demonstrations in Tibet, and at least one killed

in cold blood, probably several more."

Chinadaily.com reported on the discovery of weapons subsequent to

the protests by Buddhists monks on March 14, 2008: "Police in Lhasa

seized more than 100 guns, tens of thousands of bullets, several

thousand kilograms of explosives and tens of thousands of detonators,

acting on reports from lamas and ordinary people."

On 23 March 2008, there was a bombing incident in the Qambo prefecture.

Self-determination

While

the earliest ROC constitutional documents already claim Tibet as part

of China, Chinese political leaders also acknowledged the principle of

self-determination. For example, at a party conference in 1924,

Kuomintang leader

Sun Yat-sen issued a statement calling for the right of self-determination of all Chinese ethnic groups: "

The

Kuomintang can state with solemnity that it recognizes the right of

self-determination of all national minorities in China and it will

organize a free and united Chinese republic." In 1931, the

CCP issued a

constitution for the short-lived

Chinese Soviet Republic which states that Tibetans and other ethnic minorities, "may either join the Union of Chinese Soviets or secede from it."

It is notable that China was in a state of civil war at the time and

that the "Chinese Soviets" only represents a faction. Saying that Tibet

may secede from the "Chinese Soviets" does not mean that it can secede

from China. The quote above is merely a statement of Tibetans' freedom

to choose their political orientation. The possibility of complete

secession was denied by Communist leader

Mao Zedong

in 1938: "They must have the right to self-determination and at the

same time they should continue to unite with the Chinese people to form

one nation". This policy was codified in

PRC's first constitution which, in Article 3, reaffirmed China as a "

single multi-national state," while the "national

autonomous areas are inalienable parts". The Chinese government insists that the

United Nations documents, which codifies the principle of self-determination, provides that the principle shall not be abused in disrupting

territorial integrity:

"Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national

unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with

the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations...."

Legitimacy

The PRC also points to what it claims are the

autocratic,

oppressive and

theocratic policies of the government of Tibet before 1959, its toleration of existence of serfdom and slaves, its so-called "renunciation" of (

Arunachal Pradesh)

and its association with India and other foreign countries, and as such

claims the Government of Tibet in Exile has no legitimacy to govern

Tibet and no

credibility or justification in criticizing PRC's policies.

China claims that the People's Liberation Army's march into Tibet

in 1951 was not without the support of the Tibetan people, including

the 10th

Panchen Lama.

Ian Buruma writes:

...It is often forgotten that many

Tibetans, especially educated people in the larger towns, were so keen

to modernize their society in the mid-20th century that they saw the

Chinese communists as allies against rule by monks and serf-owning

landlords. The Dalai Lama himself, in the early 1950s, was impressed by

Chinese reforms and wrote poems praising Chairman Mao.

Instances have been documented when the PRC government gained support

from a significant portion of the Tibetan population, including

monastic leaders, monks, nobility and ordinary Tibetans prior to the crackdown in the 1959 uprising. The PRC government and many Tibetan leaders characterize PLA's operation as a peaceful liberation of Tibetans from a "feudal serfdom system." (和平解放西藏).

When Tibet complained to the United Nations through

El Salvador about Chinese invasion in November 1950—after Chinese forces entered

Chamdo (or Qamdo) when Tibet failed to respond by the deadline to China's demand for negotiation--members debated about it but refused to admit the "Tibet Question" into

the agenda of the U.N. General Assembly. Key stakeholder India told the

General Assembly that "the

Peking

Government had declared that it had not abandoned its intention to

settle the difficulties by peaceful means", and that "the Indian

Government was certain that the Tibet Question could still be settled by

peaceful means". The Russian delegate said that "China's sovereignty

over Tibet had been recognized for a long time by the United Kingdom,

the United States, and the U.S.S.R." The United Nations postponed this

matter on the grounds that Tibet was officially an "autonomous

nationality region belonging to territorial China", and because the

outlook of peaceful settlement seemed good.

Subsequently,

The Agreement Between the Central Government and the Local Government of Tibet on Method for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, also known as

Seventeen-Point Agreement,

was signed between delegates of China and Tibet on 23 May 1951. The

Dalai Lama, despite the massive Chinese military presence, had ample

time and opportunity to repudiate and denounce the Seventeen-Point

Agreement. He was encouraged and instigated to do so with promise of

public but not military support by the US, which by now had become

hostile to Communist-ruled China.

On May 29, the 10th Panchen Erdeni (i.e. 10th Panchen Lama) and

the Panchen Kampus Assembly made a formal statement, expressing their

heartfelt support for the agreement. The statement indicated their

resolution to guarantee the correct implementation of the agreement and

to realize solidarity between the different ethnic groups of China and

ethnic solidarity among the Tibetans; and on May 30, the 10th Panchen

Erdeni telegrammed the 14th Dalai Lama, expressing his hope for unity

and his vow to support the 14th Dalai Lama and the government of Tibet

with the implementation of the agreement under the guidance of the

Central Government and Chairman Mao.

The Agreement was finally accepted by Tibet's National Assembly,

which then advised the Dalai Lama to accept it. Finally, on 24 October

1951, the Dalai Lama dispatched a telegram to

Mao Zedong:

The Tibet Local Government as well

as the ecclesiastic and secular People unanimously support this

agreement, and under the leadership of Chairman Mao

and the Central People's Government, will actively support the People's

Liberation Army in Tibet to consolidate defence, drive out imperialist

influences from Tibet and safeguard the unification of the territory and

sovereignty of the Motherland.

On 28 October 1951, the Panchen Rinpoche [i.e.

Panchen Lama] made a similar public statement accepting the agreement. He urged the "people of

Shigatse to give active support" to carrying out the agreement.

Tsering Shakya writes about the general acceptance of the

Tibetans toward the Seventeen-Point Agreement, and its legal

significance:

The most vocal supporters of the

agreement came from the monastic community...As a result many Tibetans

were willing to accept the agreement....Finally there were strong

factions in Tibet who felt that the agreement was acceptable...this

section was led by the religious community...In the Tibetans' view their

independence was not a question of international legal status, but as

Dawa Norbu writes, "Our sense of independence was based on the

independence of our way of life and culture, which was more real to the

unlettered masses than law or history, canons by which the non-Tibetans

decide the fate of Tibet...This was the first formal agreement between

Tibet and Communist China and it established the legal basis for Chinese

rule in Tibet."

On March 28, 1959, premier Zhou Enlai signed the order of the PRC

State Council on the uprising in Tibet, accusing the Tibetan government

of disrupting the Agreement. The creation of the TAR finally buried the Agreement that was discarded back in 1959.

On April 18, 1959, the Dalai Lama published a statement in

Tezpur, India, that gave his reasons for escaping to India. He pointed

out that the 17 Point Agreement was signed under compulsion, and that

later "the Chinese side permanently violated it". According to Michael

Van Walt Van Praag, "treaties and similar agreements concluded under the

use or threat of force are invalid under international law ab initio".

According to this interpretation, this Agreement would not be

considered legal by those who consider Tibet to have been an independent

state before its signing, but would be considered legal by those who

acknowledge China's sovereignty over Tibet prior to the treaty.

Other accounts, such as those of Tibetologist Melvyn Goldstein, argue

that under international law the threat of military action does not

invalidate a treaty. According to Goldstein, the legitimacy of the

treaty hinges on the signatories having full authority to finalise such

an agreement; whether they did is up for debate.