From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A

two-party system is a party system where two

major political parties dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the

legislature and is usually referred to as the

majority or

governing party while the other is the

minority or

opposition party. Around the world, the term has different senses. For example, in the

United States,

Jamaica, and

Malta, the sense of

two-party system describes an arrangement in which all or nearly all elected officials belong to one of the only two major parties, and

third parties

rarely win any seats in the legislature. In such arrangements,

two-party systems are thought to result from various factors like

winner-takes-all election rules. In such systems, while chances for

third-party

candidates winning election to major national office are remote, it is

possible for groups within the larger parties, or in opposition to one

or both of them, to exert influence on the two major parties. In contrast, in

Canada, the

United Kingdom and

Australia and in other parliamentary systems and elsewhere, the term

two-party system

is sometimes used to indicate an arrangement in which two major parties

dominate elections but in which there are viable third parties which do

win seats in the legislature, and in which the two major parties exert

proportionately greater influence than their percentage of votes would

suggest.

Explanations for why a political system with free elections may

evolve into a two-party system have been debated. A leading theory,

referred to as

Duverger's law, states that two parties are a natural result of a

winner-take-all voting system.

Examples

Commonwealth countries

In countries such as

Britain,

two major parties emerge which have strong influence and tend to elect

most of the candidates, but a multitude of lesser parties exist with

varying degrees of influence, and sometimes these lesser parties are

able to elect officials who participate in the legislature. Political

systems based on the

Westminster system, which is a particular style of

parliamentary democracy based on the British model and found in many commonwealth countries, a majority party will form the

government and the minority party will form the

opposition, and coalitions of lesser parties are possible; in the rare circumstance in which neither party is the majority, a

hung parliament arises. Sometimes these systems are described as

two-party systems but they are usually referred to as

multi-party systems. There is not always a sharp boundary between a two-party system and a multi-party system.

Other parties in these countries may have seen candidates elected to

local or

subnational office, however.

In

Canada, there is a multiparty system at the federal level and in the largest provinces of

British Columbia,

Ontario,

Quebec,

Manitoba as well as the smaller

New Brunswick,

Newfoundland And Labrador,

Nova Scotia and

Yukon Territory.

However, many of the provinces have effectively become two-party

systems in which only two parties regularly get members elected.

Examples include

British Columbia (where the battles are between the

New Democratic Party and the

BC Liberals),

Alberta (between the

Alberta New Democratic Party and

United Conservative Party),

Saskatchewan (between the

Saskatchewan Party and

New Democratic Party),

New Brunswick (between the

Liberals and the

Progressive Conservatives) and

Prince Edward Island (between

Liberals and

Progressive Conservatives).

India

India has a multi-party system but also shows characteristics of a two party system with the

National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and

United Progressive Alliance (UPA)

as the two main players. Both NDA and UPA are not two political parties

but alliances of several smaller parties. Other smaller parties not

aligned with either NDA or UPA exist, and overall command about 20% of the

2009 seats in the Lok Sabha and had further increased to 28% in the

2014 general election.

Latin America

Malta

Malta is somewhat unusual in that while the electoral system is

single transferable vote

(STV), traditionally associated with proportional representation, minor

parties have not had much success. Politics is dominated between the

centre-left

Labour Party and the centre-right

Nationalist Party, with no third parties winning seats in Parliament between

1962 and

2017.

United States

During the

Third Party System, the Republican Party was the dominant political faction, but the Democrats held a strong, loyal coalition in the

Solid South. During the

Fourth Party System, the Republicans remained the dominant Presidential party, although Democrats

Grover Cleveland and

Woodrow Wilson were both elected to two terms. In

1932, at the onset of the

Fifth Party System, Democrats took firm control of national politics with the landslide victories of

Franklin D. Roosevelt in four consecutive elections. Other than the two terms of Republican

Dwight Eisenhower

from 1953 to 1961, Democrats retained firm control of the Presidency

until the mid-1960s. Since the mid-1960s, despite a number of landslides

(such as

Richard Nixon carrying 49 states and 61% of the popular vote over

George McGovern in

1972;

Ronald Reagan carrying 49 states and 58% of the popular vote over

Walter Mondale in

1984),

Presidential elections have been competitive between the predominant

Republican and Democratic parties and no one party has been able to hold

the Presidency for more than three consecutive terms. In the election

of

2012, only 4% separated the popular vote between

Barack Obama (51%) and

Mitt Romney (47%), although Obama won the electoral vote (332–206).

Throughout every American party system, no third party has won a

Presidential election or majorities in either house of Congress. Despite

that, third parties and third party candidates have gained traction and

support. In the election of

1912,

Theodore Roosevelt won 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes running as a

Progressive. In the

1992 Presidential election,

Ross Perot won 19% of the popular vote but no electoral votes running as an Independent.

Modern

American politics, in particular the

electoral college system, has been described as duopolistic since the

Republican and

Democratic parties have dominated and framed

policy debate as well as the public discourse on matters of national concern for about a century and a half.

Third Parties have encountered various blocks in

getting onto ballots

at different levels of government as well as other electoral obstacles,

such as denial of access to general election debates. Since 1987, the

Commission on Presidential Debates, established by the Republican and Democratic parties themselves, supplanting debates run since 1920 by the

League of Women Voters.

The League withdrew its support in protest in 1988 over objections of

alleged stagecraft such as rules for camera placement, filling the

audience with supporters, approved moderators, predetermined question

selection, room temperature and others. The Commission maintains its own rules for admittance and has yet to admit a third party candidate to a televised debate.

Other examples

South Korea has a multi-party system that has sometimes been described as having characteristics of a two-party system.

Furthermore,

the Lebanese Parliament is mainly made up of two

bipartisan alliances. Although both alliances are made up of several political parties on both ends of the

political spectrum the two way political situation has mainly arisen due to strong ideological differences in the electorate. Once again this can mainly be attributed to the

winner takes all thesis.

Comparisons with other party systems

Two-party systems can be contrasted with:

- Multi-party systems. In these, the effective number of parties

is greater than two but usually fewer than five; in a two-party system,

the effective number of parties is two (according to one analysis, the

actual average number of parties varies between 1.7 and 2.1.)

The parties in a multi-party system can control government separately

or as a coalition; in a two-party system, however, coalition governments

rarely form. Examples of nations with multi-party systems include Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Nepal, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Ukraine, Spain, Sweden and Taiwan.

- One-party systems or dominant-party systems

happen in nations where no more than one party is codified in law

and/or officially recognized, or where alternate parties are restricted

by the dominant party which wields power. Examples include rule by the Communist Party of China and Lao People's Revolutionary Party.

Causes

There are

several reasons why, in some systems, two major parties dominate the

political landscape. There has been speculation that a two-party system

arose in the

United States

from early political battling between the federalists and

anti-federalists in the first few decades after the ratification of the

Constitution, according to several views.

In addition, there has been more speculation that the winner-takes-all

electoral system as well as particular state and federal laws regarding

voting procedures helped to cause a two-party system.

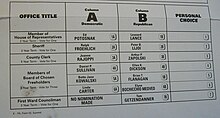

In a two-party system, voters have mostly two options; in this sample ballot for an election in

Summit,

New Jersey, voters can choose between a Republican or Democrat, but there are no third party candidates.

Political scientists such as

Maurice Duverger and

William H. Riker claim that there are strong correlations between voting rules and type of party system.

Jeffrey D. Sachs agreed that there was a link between voting arrangements and the effective number of parties. Sachs explained how the

first-past-the-post voting arrangement tended to promote a two-party system:

The main reason for America's

majoritarian character is the electoral system for Congress. Members of

Congress are elected in single-member districts according to the

"first-past-the-post" (FPTP) principle, meaning that the candidate with

the plurality of votes is the winner of the congressional seat. The

losing party or parties win no representation at all. The

first-past-the-post election tends to produce a small number of major

parties, perhaps just two, a principle known in political science as Duverger's Law. Smaller parties are trampled in first-past-the-post elections.

— Sachs, The Price of Civilization, 2011

Consider a system in which voters can vote for any candidate from any

one of many parties. Suppose further that if a party gets 15% of votes,

then that party will win 15% of the seats in the legislature. This is

termed proportional representation or more accurately as party-proportional representation.

Political scientists speculate that proportional representation leads

logically to multi-party systems, since it allows new parties to build a

niche in the legislature:

Because even a minor party may

still obtain at least a few seats in the legislature, smaller parties

have a greater incentive to organize under such electoral systems than

they do in the United States.

— Schmidt, Shelley, Bardes (2008)

In contrast, a voting system that allows only a single winner for each possible legislative seat is sometimes termed a

plurality voting system or

single-winner voting system and is usually described under the heading of a

winner-takes-all

arrangement. Each voter can cast a single vote for any candidate within

any given legislative district, but the candidate with the most votes

wins the seat, although variants, such as requiring a majority, are

sometimes used. What happens is that in a general election, a party that

consistently comes in third in every district is unlikely to win any

legislative seats even if there is a significant proportion of the

electorate favoring its positions. This arrangement strongly favors

large and well–organized political parties that are able to appeal to

voters in many districts and hence win many seats, and discourages

smaller or regional parties. Politically oriented people consider their

only realistic way to capture political power is to run under the

auspices of the two dominant parties.

In the U.S., forty-eight states have a standard

winner-takes-all electoral system for amassing presidential votes in the

Electoral College system. The

winner-takes-all principle applies in presidential elections, since if a presidential candidate gets the most votes in any particular state,

all of the

electoral votes from that state are awarded. In all but two states,

Maine and

Nebraska, the presidential candidate winning a plurality of votes wins all of the electoral votes, a practice called the

unit rule.

Duverger concluded that "plurality election single-ballot

procedures are likely to produce two-party systems, whereas proportional

representation and runoff designs encourage multipartyism." He suggested there were two reasons why

winner-takes-all systems leads to a two-party system. First, the weaker parties are pressured to form an alliance, sometimes called a

fusion,

to try to become big enough to challenge a large dominant party and, in

so doing, gain political clout in the legislature. Second, voters

learn, over time, not to vote for candidates outside of one of the two

large parties since their votes for third party candidates are usually

ineffectual.

As a result, weaker parties are eliminated by voters over time.

Duverger pointed to statistics and tactics to suggest that voters tended

to gravitate towards one of the two main parties, a phenomenon which he

called

polarization, and tend to shun third parties. For example, some analysts suggest that the

Electoral College system in the

United States, by favoring a system of winner-takes-all in presidential elections, is a structural choice favoring only two major parties.

Gary Cox suggested that America's two-party system was highly related with economic prosperity in the country:

The bounty of the American economy,

the fluidity of American society, the remarkable unity of the American

people, and, most important, the success of the American experiment have

all mitigated against the emergence of large dissenting groups that

would seek satisfaction of their special needs through the formation of

political parties.

— Cox, according to George Edwards

An effort in 2012 by centrist groups to promote

ballot access by Third Party candidates called

Americans Elect spent $15 million to get ballot access but failed to elect any candidates. The lack of choice in a two-party model in politics has often been compared to the variety of choices in the marketplace.

Politics has lagged our social and

business evolution ... There are 30 brands of Pringles in our local

grocery store. How is it that Americans have so much selection for

potato chips and only two brands – and not very good ones – for

political parties?

— Scott Ehredt of the Centrist Alliance

Third parties

According

to one view, the winner-takes-all system discourages voters from

choosing third party or independent candidates, and over time the

process becomes entrenched so that only two major parties become viable.

Third parties, meaning a party other than one of the two dominant

parties, are possible in two-party systems, but they are often unlikely

to exert much influence by gaining control of legislatures or by winning

elections.

While there are occasional opinions in the media expressed about the

possibility of third parties emerging in the United States, for example,

political insiders such as the 1980 presidential candidate John

Anderson think the chances of one appearing in the early twenty-first

century is remote. A report in

The Guardian suggested that American politics has been "stuck in a two-way fight between

Republicans and

Democrats" since the

Civil War, and that third-party runs had little meaningful success.

Third parties in a two-party system can be:

- Built around a particular ideology or interest group

- Split off from one of the major parties or

- Focused on a charismatic individual.

When third parties are built around an ideology which is at odds with

the majority mindset, many members belong to such a party not for the

purpose of expecting electoral success but rather for personal or

psychological reasons. In the U.S., third parties include older ones such as the

Libertarian Party and the

Green Party and newer ones such as the

Pirate Party.

Many believe that third parties don't affect American politics by

winning elections, but they can act as "spoilers" by taking votes from

one of the two major parties. They act like barometers of change in the political mood since they push the major parties to consider their demands. An analysis in

New York Magazine

by Ryan Lizza in 2006 suggested that third parties arose from time to

time in the nineteenth century around single-issue movements such as

abolition, women's suffrage, and the direct election of senators, but

were less prominent in the twentieth century.

A so-called

third party in the

United Kingdom are the

Liberal Democrats. In the

2010 election, the Liberal Democrats received 23% of the votes but only 9% of the seats in the

House of Commons.

While electoral results do not necessarily translate into legislative

seats, the Liberal Democrats can exert influence if there is a situation

such as a

hung parliament. In this instance, neither of the two main parties (at present, the

Conservative Party and the

Labour Party)

have sufficient authority to run the government. Accordingly, the

Liberal Democrats can in theory exert tremendous influence in such a

situation since they can ally with one of the two main parties to form a

coalition. This happened in the

Coalition government of 2010. Yet in that more than 13% of the seats in the

British House of Commons

are held in 2011 by representatives of political parties other than the

two leading political parties of that nation, contemporary Britain is

considered by some to be a

multi-party system, and not a two-party system.

The two party system in the United Kingdom allows for other parties to

exist, although the main two parties tend to dominate politics; in this

arrangement, other parties are not excluded and can win seats in

Parliament. In contrast, the two party system in the United States has

been described as a duopoly or an enforced two-party system, such that

politics is almost entirely dominated by either the

Republicans or

Democrats, and third parties rarely win seats in

Congress.

Advantages

Some

historians have suggested that two-party systems promote centrism and

encourage political parties to find common positions which appeal to

wide swaths of the electorate. It can lead to political stability which leads, in turn, to economic growth. Historian

Patrick Allitt of the

Teaching Company

suggested that it is difficult to overestimate the long-term economic

benefits of political stability. Sometimes two-party systems have been

seen as preferable to multi-party systems because they are simpler to

govern, with less fractiousness and greater harmony, since it

discourages radical minor parties, while multi-party systems can sometimes lead to

hung parliaments.

Italy,

with a multi-party system, has had years of divisive politics since

2000, although analyst Silvia Aloisi suggested in 2008 that the nation

may be moving closer to a two-party arrangement. The two-party has been identified as simpler since there are fewer voting choices.

Disadvantages

Two-party systems have been criticized for downplaying alternative views, being less competitive, encouraging voter apathy since there is a perception of fewer choices, and putting a damper on debate

[5]

within a nation. In a proportional representation system, lesser

parties can moderate policy since they are not usually eliminated from

government. One analyst suggested the two-party approach may not promote inter-party compromise but may encourage partisanship. In

The Tyranny of the Two-party system,

Lisa Jane Disch criticizes two-party systems for failing to provide

enough options since only two choices are permitted on the ballot. She

wrote:

Herein lies the central tension of the two–party doctrine. It identifies popular sovereignty

with choice, and then limits choice to one party or the other. If there

is any truth to Schattschneider's analogy between elections and

markets, America's faith in the two–party system begs the following

question: Why do voters accept as the ultimate in political freedom a

binary option they would surely protest as consumers? ... This is the

tyranny of the two–party system, the construct that persuades United States citizens to accept two–party contests as a condition of electoral democracy.

— Lisa Jane Disch, 2002

There have been arguments that the winner-take-all mechanism

discourages independent or third-party candidates from running for

office or promulgating their views.

Ross Perot's

former campaign manager wrote that the problem with having only two

parties is that the nation loses "the ability for things to bubble up

from the body politic and give voice to things that aren't being voiced

by the major parties."

One analyst suggested that parliamentary systems, which typically are

multi-party in nature, lead to a better "centralization of policy

expertise" in government.

Multi-party governments permit wider and more diverse viewpoints in

government, and encourage dominant parties to make deals with weaker

parties to form winning coalitions. Analyst Chris Weigant of

the Huffington Post

wrote that "the parliamentary system is inherently much more open to

minority parties getting much better representation than third parties

do in the American system". After an election in which the party changes, there can be a "polar shift in policy-making" when voters react to changes.

Political analyst A. G. Roderick, writing in his book

Two Tyrants,

argued that the two American parties, the Republicans and Democrats,

are highly unpopular in 2015, and are not part of the political

framework of state governments, and do not represent 47% of the

electorate who identify themselves as "independents". He makes a case that the

American president should be elected on a non-partisan basis, and asserts that both political parties are "cut from the same cloth of corruption and corporate influence."

History

Beginnings of parties in Britain

Equestrian portrait of William III by

Jan Wyck, commemorating the landing at Brixham, Torbay, 5 November 1688

The two-party system, in the sense of the looser definition, where

two parties dominate politics but in which third parties can elect

members and gain some representation in the legislature, can be traced

to the development of political parties in the

United Kingdom. There was a division in

English politics at the time of the

Civil War and

Glorious Revolution in the late 17th century. The

Whigs supported

Protestant constitutional monarchy against

absolute rule and the

Tories, originating in the

Royalist (or "

Cavalier") faction of the

English Civil War, were conservative royalist supporters of a strong monarchy as a counterbalance to the

republican tendencies of

Parliament. In the following century, the Whig party's support base widened to include emerging industrial interests and wealthy merchants.

Vigorous struggle between the two factions characterised the period from the

Glorious Revolution to the 1715

Hanoverian succession, over the legacy of the overthrow of the

Stuart dynasty

and the nature of the new constitutional state. This proto two-party

system fell into relative abeyance after the accession to the throne of

George I and the consequent period of

Whig supremacy under

Robert Walpole,

during which the Tories were systematically purged from high positions

in government. However, although the Tories were dismissed from office

for half a century, they still retained a measure of party cohesion

under

William Wyndham

and acted as a united, though unavailing, opposition to Whig corruption

and scandals. At times they cooperated with the "Opposition Whigs",

Whigs who were in opposition to the Whig government; however, the

ideological gap between the Tories and the Opposition Whigs prevented

them from coalescing as a single party.

Emergence of the two-party system in Britain

The old Whig leadership dissolved in the 1760s into a decade of factional chaos with distinct "

Grenvillite", "

Bedfordite", "

Rockinghamite", and "

Chathamite"

factions successively in power, and all referring to themselves as

"Whigs". Out of this chaos, the first distinctive parties emerged. The

first such party was the

Rockingham Whigs under the leadership of

Charles Watson-Wentworth and the intellectual guidance of the

political philosopher Edmund Burke.

Burke laid out a philosophy that described the basic framework of the

political party as "a body of men united for promoting by their joint

endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in

which they are all agreed". As opposed to the instability of the earlier

factions, which were often tied to a particular leader and could

disintegrate if removed from power, the two party system was centred on a

set of core principles held by both sides and that allowed the party

out of power to remain as the

Loyal Opposition to the governing party.

In

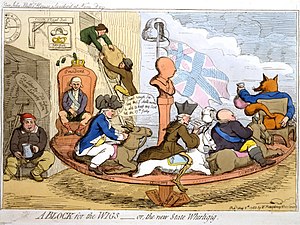

A Block for the Wigs (1783),

James Gillray caricatured Fox's return to power in a coalition with

North. George III is the blockhead in the center.

The two party system matured in the early 19th century

era of political reform,

when the franchise was widened and politics entered into the basic

divide between conservatism and liberalism that has fundamentally

endured up to the present. The modern

Conservative Party was created out of the

"Pittite" Tories by

Robert Peel, who issued the

Tamworth Manifesto in 1834 which set out the basic principles of

Conservatism

– the necessity in specific cases of reform in order to survive, but an

opposition to unnecessary change, that could lead to "a perpetual

vortex of agitation". Meanwhile, the Whigs, along with

free trade Tory followers of

Robert Peel, and independent

Radicals, formed the

Liberal Party under

Lord Palmerston in 1859, and transformed into a party of the growing urban middle-class, under the long leadership of

William Ewart Gladstone. The two party system had come of age at the time of Gladstone and his Conservative rival

Benjamin Disraeli after the

1867 Reform Act.

History of American political parties