Left-wing nationalism or leftist nationalism is a form of nationalism based upon national self-determination, popular sovereignty, national self-interest, and left-wing political positions such as social equality. Left-wing nationalism can also include anti-imperialism and national liberation movements. Left-wing nationalism often stands in contrast to right-wing politics and right-wing nationalism.

Overview

Terms such as nationalist socialism, social nationalism and socialist nationalism are not to be confused with the German fascism espoused by the Nazi Party which called itself National Socialism. This ideology advocated the supremacy and territorial expansion of the German nation, while opposing popular sovereignty, social equality and national self-determination for non-Germans. Left-wing nationalism does not promote the view that one nation is superior to others.

Some left-wing nationalist groups have historically used the term national socialism for themselves, but only before the rise of the Nazis or outside Europe. Since the Nazis' rise to prominence, national socialism has become associated almost exclusively with their ideas and it is rarely used in relation to left-wing nationalism in Europe, with nationalist socialism or socialist nationalism being preferred over national socialism.

Notable left-wing nationalist movements include the African National Congress of South Africa under Nelson Mandela; Basque nationalism and the EH Bildu coalition as well as the Catalan independence movement and the Galician nationalism and Galician Nationalist Bloc party in Spain; Labor Zionism in Israel; the League of Communists of Yugoslavia; the Malay Nationalist Party of Malaysia; the Mukti Bahini in Bangladesh; Quebec nationalism and the Parti Québécois, Québec solidaire and Bloc Québécois in Canada; the Scottish National Party which promotes Scottish independence from the United Kingdom; Sinn Féin, an Irish republican party in Ireland; and the Vietcong in Vietnam.

Socialist nationalism

Marxism identifies the nation as a socioeconomic construction created after the collapse of the feudal system which was utilized to create the capitalist economic system. Classical Marxists have unanimously claimed that nationalism is a bourgeois phenomenon that is not associated with Marxism. In certain instances, Marxism has supported patriotic movements if they were in the interest of class struggle, but rejects other nationalist movements deemed to distract workers from their necessary goal of defeating the bourgeoisie. Marxists have evaluated certain nations to be progressive and other nations to be reactionary. Joseph Stalin supported interpretations of Marx tolerating the use of proletarian patriotism that promoted class struggle within an internationalist framework.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels interpreted issues concerning nationality on a social evolutionary basis. Marx and Engels claim that the creation of the modern nation state is the result of the replacement of feudalism with the capitalist mode of production. With the replacement of feudalism with capitalism, capitalists sought to unify and centralize populations' culture and language within states in order to create conditions conducive to a market economy in terms of having a common language to coordinate the economy, contain a large enough population in the state to insure an internal division of labor and contain a large enough territory for a state to maintain a viable economy.

Although Marx and Engels saw the origins of the nation state and national identity as bourgeois in nature, both believed that the creation of the centralized state as a result of the collapse of feudalism and creation of capitalism had created positive social conditions to stimulate class struggle. Marx followed Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view that the creation of individual-centered civil society by states as a positive development in that it dismantled previous religious-based society and freed individual conscience. In The German Ideology, Marx claims that although civil society is a capitalist creation and represents bourgeois class rule, it is beneficial to the proletariat because it is unstable in that neither states nor the bourgeoisie can control a civil society. Marx described this in detail in The German Ideology, stating:

Civil society embraces the whole material intercourse of individuals within a definite stage of development of productive forces. It embraces the whole commercial and industrial life of a given stage, and, insofar, transcends the state and the nation, though on the other hand, it must assert itself in its foreign relations as nationality and inwardly must organize itself as a state.

Marx and Engels evaluated progressive nationalism as involving the destruction of feudalism and believed that it was a beneficial step, but they evaluated nationalism detrimental to the evolution of international class struggle as reactionary and necessary to be destroyed. Marx and Engels believed that certain nations that could not consolidate viable nation-states should be assimilated into other nations that were more viable and further in Marxian evolutionary economic progress.

On the issue of nations and the proletariat, The Communist Manifesto says:

The working men have no country. We cannot take from them what they have not got. Since the proletariat must first of all acquire political supremacy, must rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation, it is so far, itself national, though not in the bourgeois sense of the word. National differences and antagonism between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto. The supremacy of the proletariat will cause them to vanish still faster. United action, of the leading civilized countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

In general, Marx preferred internationalism and interaction between nations in class struggle, saying in Preface to the Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy that "[o]ne nation can and should learn from others". Similarly, although Marx and Engels criticized Irish unrest for delaying a worker's revolution in England, they believed that Ireland was oppressed by Great Britain, but that the Irish people would better serve their own interests by joining proponents of class struggle in Europe as Marx and Engels claimed that the socialist workers of Europe were the natural allies of Ireland. Marx and Engels also believed that it was in Britain's best interest to let Ireland go as the Ireland issue was being used by elites to unite the British working class with the elites against the Irish.

Stalinism and revolutionary patriotism

Joseph Stalin promoted a civic patriotic concept called revolutionary patriotism in the Soviet Union. As a youth, Stalin had been active in the Georgian nationalist movement and was influenced by Ilia Chavchavadze, who promoted cultural nationalism, material development of the Georgian people, statist economy and education systems. When Stalin joined the Georgian Marxists, Marxism in Georgia was heavily influenced by Noe Zhordania, who evoked Georgian patriotic themes and opposition to Russian imperial control of Georgia. Zhordania claimed that communal bonds existed between peoples that created the plural sense of I of countries and went further to say that the Georgian sense of identity pre-existed capitalism and the capitalist conception of nationhood.

After becoming a Bolshevik in the 20th century, he became fervently opposed to national culture, denouncing the concept of contemporary nationality as bourgeois in origin and accused nationality of causing retention of "harmful habits and institutions". However, Stalin believed that cultural communities did exist where people lived common lives and were united by holistic bonds, claiming that there were real nations while others that did not fit these traits were paper nations. Stalin defined the nation as being "neither racial nor tribal, but a historically formed community of people". Stalin believed that the assimilation of primitive nationalities like Abkhazians and Tartars into the Georgian and Russian nations was beneficial. Stalin claimed that all nations were assimilating foreign values and that the nationality as a community was diluting under the pressures of capitalism and with rising rational universality.

In 1913, Stalin rejected the concept of national identity entirely and advocated in favor of a universal cosmopolitan modernity. Stalin identified Russian culture as having greater universalist identity than that of other nations. Stalin's view of vanguard and progressive nations such as Russia, Germany and Hungary in contrast to nations he deemed primitive is claimed to be related to Engels' views.

Titoism

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia under the rule of Josip Broz Tito and the League of Communists of Yugoslavia promoted both Marxism–Leninism and Yugoslav nationalism (Yugoslavism), i.e. socialist patriotism. Tito's Yugoslavia was overtly nationalistic in its attempts to promote unity between the Yugoslav nations within Yugoslavia and asserting Yugoslavia's independence. To unify the Yugoslav nations, the government promoted the concept of brotherhood and unity in which the Yugoslav nations would overcome their cultural and linguistic differences through promoting fraternal relations between the nations. This nationalism was opposed to cultural assimilation as had been carried out by the previous Yugoslav monarchy, but it was instead based upon multiculturalism.

While promoting a Yugoslav nationalism, the Yugoslav government was staunchly opposed to any factional ethnic nationalism or domination by the existing nationalities as Tito denounced ethnic nationalism in general as being based on hatred and was the cause of war. The League of Communists of Yugoslavia blamed the factional division and conflict between the Yugoslav nations on foreign imperialism. Tito built strong relations with states that had strong socialist and nationalist governments in power such as Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser and India under Jawaharlal Nehru. In spite of these attempts to create a left-wing Yugoslav national identity, factional divisions between Yugoslav nationalities remained strong and it was largely the power of the party and popularity of Tito that held the country together.

Progressive nationalism

In general, modern left-wing nationalism is associated with socialism, but non-socialist left-wing nationalism also exists. Nationalism that is culturally and economically progressive is called "progressive nationalism". This non-socialist modern left-wing nationalism is prominent in some regions, like South Korea. Some modern social-liberals argue that "progressive nationalism" is necessary to promote social and economic equality and develop democracy.

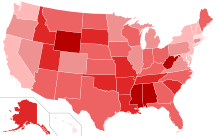

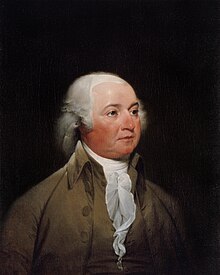

Theodore Roosevelt was a leading American progressive nationalist. Giuseppe Mazzini and other left-wing classical radicals also supported nationalism.

By country

Africa

Mauritius

The Mauritian Militant Movement (MMM) is a political party in Mauritius formed by a group of students in the late 1960s, advocating independence from the United Kingdom, socialism and social unity. The MMM advocates what it sees as a fairer society, without discrimination on the basis of social class, race, community, caste, religion, gender or sexual orientation.

The MMM was founded in 1968 as a students' movement by Paul Bérenger, Dev Virahsawmy, Jooneed Jeeroburkhan, Chafeekh Jeeroburkhan, Sushil Kushiram, Tirat Ramkissoon, Krishen Mati, Ah-Ken Wong, Kriti Goburdhun, Allen Sew Kwan Kan, Vela Vengaroo and Amedee Darga amongst others. In 1969, it became the MMM. The party is a member of the Socialist International as well as the Progressive Alliance, an international grouping of socialist, social-democratic and labour parties.

Ethiopia

The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) (Tigrinya: ህዝባዊ ወያነ ሓርነት ትግራይ, ḥəzbawi wäyanä ḥarənnät təgray, "Popular Struggle for the Freedom of Tigray"; widely known by pejorative names Woyane, Wayana (Amharic: ወያነ) or Wayane (ወያኔ) in older texts and Amharic publications) is a political party in Ethiopia, established on 18 February 1975 in Dedebit, northwestern Tigray, according to official records. As a strategy, TPLF used guerilla tactics as it saw those as befitting to a Marxist–Leninist political organization. Within 16 years, it had grown from about a dozen men into the most powerful armed liberation movement in Ethiopia. It led a coalition of movements named the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) from 1989 to 2018. With the help of its former ally, the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), EPRDF overthrew the dictatorship of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) and established a new government on 28 May 1991 that ruled Ethiopia.

Americas

Latin America

Left-wing nationalism has inspired many Latin American military personnel, who are receptive to this doctrine because of the repeated interference of the United States in the political and economic affairs of their countries and the social misery in the continent. While some of the military regimes such as the Argentine dictatorship and the Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile were right-wing, left-wing soldiers seized power in Peru during the 1968 military coup and established a Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces headed by General Juan Velasco Alvarado. Although it was dictatorial in nature, it did not adopt a repressive character as the regimes mentioned above. Similarly and also in 1968, General Omar Torrijos seized power in Panama, allied himself with Cuba and the Sandinistas of Nicaragua and above all led a fierce battle against the United States for the nationalisation of the Panama Canal.

North America

Canada

In Canada, nationalism is associated with the left in the context of both Quebec nationalism and pan-Canadian nationalism (mostly in English Canada, but also in Quebec).

In Quebec, the term was used by S. H. Milner and H. Milner to describe political developments in 1960s and 1970s Quebec which they saw as unique in North America. While the Liberals of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec had opposed Quebec nationalism which had been right-wing and reactionary, nationalists in Quebec now found that they could only maintain their cultural identity by ridding themselves of foreign elites, which was achieved by adopting radicalism and socialism. This ideology was seen in contrast to historic socialism, which was internationalist and considered the working class to have no homeland.

The 1960s in Canada saw the rise of a movement in favour of the independence of Quebec. Among the proponents of this constitutional option for Quebec were militants of an independent and socialist Quebec. Prior to the 1960s, nationalism in Quebec had taken various forms. First, a radical liberal nationalism emerged and was a dominant voice in the political discourse of Lower Canada from the early 19th century to the 1830s. The 1830s saw the more vocal expression of a liberal and republican nationalism which was silenced with the rebellions of 1837 and 1838. In a now annexed Lower Canada in the 1840s, a moderately liberal expression of nationalism succeeded the old one, which remained in existence but was confined to political marginality thereafter. In parallel to this, a new Catholic and ultramontane nationalism emerged. Antagonism between the two incompatible expressions of nationalism lasted until the 1950s.

According to political scientist Henry Milner, the manifestation of a third kind of nationalism became significant when intellectuals raised the issue of the economic colonization of Quebec, something the established nationalists elites had neglected to do. Milner identifies three distinct clusters of factors in the evolution of Quebec toward left-wing nationalism: the first cluster relates to the national consciousness of Quebecers (Québécois); the second to changes in technology, industrial organization and patterns of communication and education; and the third related to "the part played by the intellectuals in the face of changes in the first two factors".

In English Canada, support for government intervention in the economy to defend the country from foreign (i.e. American) influences is one of Canada's oldest political traditions, going back at least to the National Policy (tariff protection) of Sir John A. Macdonald, can historically be seen on both the left and the right. However, calls for more extreme forms of government involvement to forestall a putative American takeover have been a staple of the Canadian left since the 1920s and possibly earlier. Right-wing nationalism has never supported such measures, which is one of the major differences between the two. Leftist nationalism has also been more eager to dispense with historical Canadian symbols associated with Canada's British colonial heritage, such as the Canadian Red Ensign or even the monarchy (see republicanism in Canada). English Canadian leftist nationalism has historically been represented by most of Canada's socialist parties, factions with the social-democratic New Democratic Party (such as the Movement for an Independent Socialist Canada in the 1960s and 1970s) and in a more diluted form in some elements of the Liberal Party of Canada (such as Trudeauism to a certain extent), manifesting itself in pressure groups such as the Council of Canadians. This type of nationalism is associated with the slogan "It's either the state or the States", coined by the Canadian Radio League in the 1930s during their campaign for a national public broadcaster to compete with the private American radio stations broadcasting into Canada, representing a fear of annexation by the United States. Right-wing nationalism continues to exist in Canada, but it tends to be much less concerned with integration into North America, especially since the Conservative Party embraced free trade after 1988. Many far-right movements in Canada are nationalist, but not Canadian nationalist, instead advocating for Western separation or union with the United States.

United States

The American Indian Movement (AIM) has been committed to improving conditions faced by native peoples. It founded institutions to address needs, including the Heart of The Earth School, the Little Earth Housing, the International Indian Treaty Council, the AIM StreetMedics, the American Indian Opportunities and the Industrialization Center (one of the largest Indian job training programs) as well as the KILI radio and the Indian Legal Rights Centers.

In 1971, several members of the AIM, including Dennis Banks and Russell Means, traveled to Mount Rushmore. They converged at the mountain in order to protest the illegal seizure of the Sioux Nation's sacred Black Hills in 1877 by the United States federal government which was in violation of its earlier 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The protest began to publicize the issues of the American Indian Movement. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had illegally taken the Black Hills. The government offered financial compensation, but the Oglala Sioux have refused it, insisting on return of the land to their people. The settlement money is earning interest.

East Asia

South Korea

South Korea's progressive nationalism is a combination of 'cultural' civic nationalism and 'resistance' minjok ideology. Progressive nationalists see the elimination of hierarchical "pro-Japanese (partially pro-Chinese and pro-American) colonialist" remnants through nationalism as a prerequisite for realizing social progressivism. For example, feminist movement in South Korea often has anti-Japanese sentiment. This was naturally formed by war crimes committed by the Japanese Empire during the past World War II, such as Korean Women's Volunteer Labour Corps, Comfort Women, etc.

Historically, Korea's classical liberals have hated and resisted Qing dynasty (China) and Empire of Japan rather than the classical conservatives who conform to the powers. Due to the history of the division of Korea led by the United States and the Soviet Union, where Koreans' self-determination was ignored, Korean nationalism became more prominent in the liberal and progressive camp than in the conservative camp in South Korea. South Korea's "progressive-nationalists" criticize conservative "New Rightists" for having a sadaejuui perception of the United States, anti-communist hatred of North Korea, and supporting pro-Japanese colonialist view. The Korean nationalist sentiment of South Korean progressives also has other factors, which stem from the historical fact that some Korean conservative elites were pro-Japanese fascists.

Progressive nationalists support Israel's anti-German Jewish nationalism and punishment of Nazi collaborators. (However, Progressive nationalists have no unified view of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.) Progressive nationalists are very positive about the liquidation of Chindokpa (친독파, "pro-German faction" or "Nazi collaborators") during France's Gaullist politics and criticize South Korea for failing to liquidate Chinilpa (친일파, "pro-Japan faction"). They argue that the liquidation of Chinilpa helps the development of democracy. Progressive nationalists advocate the 'anti-German based nationalism' of French and Israeli right-wing, criticizing South Korean conservatives for not having 'anti-Japanese based nationalism' because they are pro-Japanese based colonialists. Progressive nationalists is anti-Chinese, anti-Japanese, and some anti-American sentiment, so they are very friendly to Russia. Unlike China and Japan, Russia has never invaded Korea, and politically, Russia and [North and South] Korea do not have much conflict. Some progressive nationalist media advocated Aleksandr Dugin's Eurasianism. However, they are against [South] Korean fascism.

Modern-style left-wing nationalism was formed in the 1980s. At that time, South Korean activist groups showed anti-American tendencies because the United States approved the Chun Doo-hwan administration, citing anti-communism, and was silent on the massacre in Gwangju. As a result, many of the close South Korean liberal activists, who had pursued a somewhat pro-American and moderate democratic path until the 1970s, began to turn into left-wing activists due to their betrayal they felt toward the United States. At that time, South Korea's left-wing activists were divided into two factions, 'PD' (Korean: 민중민주파; lit. People's Democracy-faction) and 'NL' (Korean: 민족해방파; lit. National Liberation-faction), and they are fiercely opposed. In the case of 'PD', it opposes nationalism by advocating European socialism or Soviet communism, but 'NL' takes a leftist Korean nationalist and anti-imperialist line based on strong anti-American imperialism and anti-Japanese imperialism.

All leftist nationalists in South Korea are opposition to Japanese imperialism, friendly relations with Russia and support the Sunshine Policy toward North Korea, but the Centre-left (liberal) nationalist and the Far-left (NL) nationalist differ significantly in their attitudes toward United States in the 21st century. Far-left nationalists and Centre-left nationalists are also criticizing each other.

- Centre-left nationalists (mainly the Democratic Party of Korea, Justice Party, etc.) that the presence of American troops is necessary to protect South Korea's sovereignty against Chinese/Japanese "invasion" (침략) of South Korea, and believe it can transform North Korea into a "pro-American" (친미) state. They are diplomatically pro-American, but at the same time somewhat pro-Russian (친러), and tend to distrust China and Japan.

- Far-left nationalists (mainly the Progressive Party, etc.) are "anti-American" (반미), support the "withdrawal of U.S. troops" (미군 철수) and "Dissolution of the U.S.-South Korea alliance" (한미동맹 파기) because they deny the hierarchy itself between countries.

Taiwan (Republic of China)

Taiwan's left-wing nationalist movement tends to emphasize the "Taiwanese identity" separated from China. As a result, Taiwan's left-wing nationalism takes a pro-American stand to counter "Chinese imperialism", even though it has initially been influenced by Western socialist movements, including Leninism.

Europe

Historically, left-wing nationalists have often emerged in European states whose borders had been formed by medieval dynastic unity, bringing together multiple linguistic and ethnic groups into one single state. During the 18th and 19th centuries, those centralised states began to promote cultural homogenisation. In reaction, some regions developed their own progressive nationalism. This often occurred in regions whose cultural, economic or sociological distinctiveness from the dominant culture had produced historical grievances (political discrimination such as the Irish Penal Laws, economic crisis such as the Irish Great Famine, or traumatic war deaths). The idea could gain ground that government by distant economic or aristocratic elites was responsible for current misfortune, but that self-rule could remedy the situation by allowing a more egalitarian or state-interventionist approach, better suited to local tastes or needs, than the royal or imperial state.

Left-wing nationalists have been prominent in leading the autonomist and separatist movements in the Basque Country (Basque nationalism); Catalonia (Catalan independence); Corsica (Corsican nationalism); Galicia (Galician nationalism); the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (Irish republicanism and Irish nationalism); Sardinia (Sardinian nationalism); Scotland (Scottish nationalism); and Wales (Welsh nationalism).

France

In Europe, a number of left-wing nationalist movements exist and have a long and well-established tradition. Nationalism originated as a left-wing position during the French Revolution and the French Revolutionary Wars. The original left-wing nationalists endorsed civic nationalism which defined the nation as a daily plebiscite and as formed by the subjective will to live together. Related to revanchism, the belligerent will to take revenge against Germany and retake control of Alsace-Lorraine, nationalism could then be sometimes opposed to imperialism. In practice, motivated by the dual idea of liberating areas from conservative rule and that those liberated peoples could be absorbed into the civic nation, French left-wing nationalism often ended up justifying or rationalising imperialism, notably in the case of Algeria.

France's centralist left-wing nationalism was at times resisted by provincial left-wing groups who saw its Paris-focussed cultural and administrative centralism as little different in practice to right-wing French nationalism. From the late 19th century, several of the many ethnic groups that made up France developed a movement for separatism and regionalism, becoming a significant political factor in Alsace, Brittany, Corsica, French Flanders and the French portions of the Basque and Catalan countries, with smaller movements in other parts of the country and eventually equivalent movements in overseas territories (Algeria and New Caledonia, among others). These regional nationalisms could be either left-wing or right-wing. For instance, Occitan nationalism in the early 20th century was expressed by the far-right leaders Maurice Barrès and Charles Maurras (who imagined a right-wing Occitan regionalist identity within a multiethnic French state as a bulwark to protect conservative zones against left-wing Parisian governments) whereas the Félibriges movement represented a more progressive Occitan nationalism and looked for inspiration to the federalist republicanism of Catalonia. It was a similar situation in each of the traditionally regionalist zones, including the left-wing Breton Federalist League against the right-wing Breton National Party and the left-wing Alsatian Progress Party against the right-wing Heimatsbund, among others. Since the 1970s, a cultural revival and left-wing nationalism has grown in strength in several regions. For instance, the Pè a Corsica party has close links with both social democracy and the green movement and is currently the dominant political force in Corsica. After the 2017 legislative election, the party obtained three-quarters of Corsican seats in the National Assembly and two-thirds in the Corsican Assembly.

Ireland

Irish nationalism has been left-wing nationalism since its mainstream inception. Early nationalists during the 19th century such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, Fenian Brotherhood in the 1880s, as well as Sinn Féin, and Fianna Fáil in the 1920s all styled themselves in various ways after French left-wing radicalism and republicanism. This combination of nationalism with left-wing positions was possible as the nation state they sought was envisaged against the backdrop of the more socially conservative and pluri-national state of the United Kingdom.

Today, parties such as Sinn Féin and the Social Democratic and Labour Party in Northern Ireland are left-wing nationalist parties. Earlier nationalist republican parties that were once rather more left-leaning for the time, notably Fianna Fáil in the Republic of Ireland, have over time grown more conservative ("sinistrism"), today representing a centrist or centre-right republican nationalism. Right-wing nationalist outlooks and far-right parties in general are few in Irish history. When they did emerge, it was usually short-lived and contextual (the Blueshirts during the Great Depression) or took the form of Anglo-British nationalism (as with Orangism and other tendencies within Ulster unionism). Since World War II, right-wing Irish nationalism has been a rare force in the Republic of Ireland, espoused primarily by small, often short-lived organisations. As such, left-wing nationalism with a republican, egalitarian, anti-colonial tendency has historically been the dominant form of nationalism in Irish politics.

Poland

In the late 19th century, Polish labour movement split into two factions, with one proposing communist revolution and Polish autonomy within the Russian Empire which established the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania, renamed later as the Communist Party of Poland. However, most activists have seen Polish independence as a requirement to realize socialist political program as after Poland partitions Austria-Hungary, Prussia and Russia repressed their ethnically Polish citizens of all social classes. Those activists established Polish Socialist Party (PPS). During World War I, PPS' leader Józef Piłsudski became a leader of German dominated puppet Poland and then broke an alliance with Central Powers, claiming an independent Second Polish Republic. As a Chief of State, Piłsudski signed in very first weeks decrees about the eight hour work day, equal rights for women, free and compulsory education, free healthcare and social insurance, making Poland one of the most progressive countries of interwar period.

In Poland itself, the PPS is considered pro-independence and patriotic left-wing (in contrast with the internationalist left-wing) rather than left-wing nationalist. The term nationalism is used nearly exclusively for the right-wing national democracy of Roman Dmowski and other officially far-right movements such as National Radical Camp and National Revival of Poland. Nowadays, notable parties and organizations that come the closest to the idea of a left-wing nationalism are Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland under the leadership of Andrzej Lepper and Zmiana led by Mateusz Piskorski. Both advocate patriotism, social conservatism, Euroscepticism, anti-imperialism (strong criticism of a NATO and American foreign policies) and economic nationalism. The Self-Defence won 53 seats out of 460 in 2001 elections and 56 in 2005. From 2005 to 2007, it was in the coalition government with two other parties (one right-wing and the other nationalist). Since then, it has no representatives in the Polish Sejm.

It could be argued that the ruling Law and Justice party exhibits forms of left-wing nationalism. On economic issues, the party takes partial stance against privatization and pushes for a strong state role in the market. On social issues, the party is very conservative and often alludes to the policies of the interwar sanation movement which was led by Józef Piłsudski.

Scotland

The Scottish independence movement is mainly left-wing and is spearheaded by the Scottish National Party, who have been on the centre-left since the 1970s. There are other political parties from the political left in favour of Scottish independence, namely the Scottish Greens, the Scottish Socialist Party and Solidarity.

Spain

The Anova–Nationalist Brotherhood is a Galician nationalist left-wing party that supports Galician independence from the Spanish government. In addition to national liberation, Anova defines itself as a socialist, feminist, ecologist and internationalist organization. Its internal organization is run by assemblies.

Bildu is the political party that represents leftist Basque nationalism. In Catalonia, there are two main political parties which defend the Catalan left-wing independentist movement, both with institutional representation, which are the Republican Left of Catalonia and Popular Unity Candidacy.

Turkey

In Turkey, Republican People's Party and the Enlightenment Movement (Aydınlık Hareketi) have been synonymous with left-wing nationalism. Enlightenment Movement has been advocated by the Patriotic Party.

Ukraine

In Ukraine, the national question and the agrarian question especially before the Russian Revolution were highly entangled. This led to the Borotbists.

Wales

Similarly to Scotland, there is a left-wing movement in Wales led by Plaid Cymru for Welsh independence. Previously in favour of a revolutionary form of independence, Plaid now considers itself to be evolutionary in its approach to independence through continued devolution and ultimate sovereignty. This is also the view of the Wales Green Party.

Oceania

Australia

During the 1890s, Australian-born novelists and poets such as Henry Lawson, Joseph Furphy and Banjo Paterson drew on the archetype of the Australian bushman. These and other writers formulated the bush legend which included broadly left-wing notions that working class Outback Australians were democratic, egalitarian, anti-authoritarian and cultivated mateship. However, terms like nationalist and patriotic were also utilised by pro-British Empire political conservatives, culminating with the formation in 1917 of the Nationalist Party of Australia which remained the main centre-right party until the late 1920s.

During the 1940s and 1950s, radical intellectuals, many of whom joined the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), combined philosophical internationalism with a radical nationalist commitment to Australian culture. This type of cultural nationalism was possible among radicals in Australia at the time because of the patriotic turn in Comintern policy from 1941; the most common understanding of what it meant to be patriotic at the time was a kind of pro-imperial race patriotism and anti-British sentiment was until the late 1960s regarded as subversive; and radical nationalism dovetailed with a growing respect for Australian cultural output among intellectuals which was itself a product of the break in cultural supply chains—lead actors and scripts had always come from Britain and the United States—occasioned by the war.

Post-war radical nationalists consequently sought to canonise the bush culture which had emerged during the 1890s. The post-war radical nationalists interpreted this tradition as having implicitly or inherently radical qualities since they believed it meant that working-class Australians were naturally democratic and/or socialist. This view combined the CPA's commitment to the working class with the post-war intellectuals' own nationalist sentiments. The apotheosis of this line of thought was perhaps Russel Ward's book The Australian Legend (1958) which sought to trace the development of the radical nationalist ethos from its convict origins through bushranging, the Victorian gold rush, the spread of agriculture, the industrial strife of the early 1890s and its literary canonisation. Other significant radical nationalists included the historians Ian Turner, Lloyd Churchward, Robin Gollan, Geoffrey Serle and Brian Fitzpatrick, whom Ward described as the "spiritual father of all the radical nationalist historians in Australia"; and the writers Stephen Murray-Smith, Judah Waten, Dorothy Hewett and Frank Hardy.

The Barton Government which came to power following the first elections to the Commonwealth parliament in 1901 was formed by the Protectionist Party with the support of the Australian Labor Party. The support of the Labor Party was contingent upon restricting non-white immigration, reflecting the attitudes of the Australian Workers Union and other labour organisations at the time, upon whose support the Labor Party was founded.

At the start of World War II, Labor Prime Minister John Curtin reinforced the message of the White Australia policy by saying: "This country shall remain forever the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race".

Labor Party leader Arthur Calwell supported the White European Australia policy. This is reflected by Calwell's comments in his 1972 memoirs Be Just and Fear Not in which he made it clear that he maintained his view that non-European people should not be allowed to settle in Australia, writing:

I am proud of my white skin, just as a Chinese is proud of his yellow skin, a Japanese of his brown skin, and the Indians of their various hues from black to coffee-coloured. Anybody who is not proud of his race is not a man at all. And any man who tries to stigmatize the Australian community as racist because they want to preserve this country for the white race is doing our nation great harm. [...] I reject, in conscience, the idea that Australia should or ever can become a multi-racial society and survive.

The radical-nationalist tradition was challenged during the 1960s, during which New Left scholars interpreted much of Australian history—including labour history—as dominated by racism, sexism, homophobia and militarism. Since the 1960s, it has been uncommon for those on the political left to claim Australian nationalism for themselves. The bush legend has survived the above changes in Australian culture as it informed much cultural output during the period of the new nationalism in the 1970s and 1980s, the language of Australian nationalism was adopted by centre-right politicians such as Prime Minister John Howard for the political right during the 1990s. In the 21st century, attempts by left-leaning intellectuals to reclaim nationalism for the left are few and far between.

South Asia

Bangladesh

After its 1971 liberation war, Bangladesh wrote its binding beliefs to be for "Secularism, Nationalism and Socialism". For a long time, Bengali nationalism was promoted in Bangladesh while excluding other minorities which led to President Ziaur Rahman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) to change Bengali nationalism to Bangladeshi nationalism where all citizens of the country is equal under the law. This new nationalism in Bangladesh has been promoted by the BNP and the Awami League calling for national unity and cultural promotion. However, the BNP would later promote Islamic unity as well and has excluded Hindus from the national unity while bringing together Bihari Muslims and Chakma Buddhists. This is different from Awami League's staunch secularist stance of the national identity uniting all religious minorities.