From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Winning family of a Fitter Family contest stand outside of the Eugenics Building (where contestants register) at the Kansas Free Fair, in Topeka, KS.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States during the Progressive Era, from the late 19th century until US involvement in World War II.

While ostensibly about improving genetic quality, it has been

argued that eugenics was more about preserving the position of the

dominant groups in the population. Scholarly research has determined

that people who found themselves targets of the eugenics movement were

those who were seen as unfit for society—the poor, the disabled, the

mentally ill, and specific communities of color—and a disproportionate

number of those who fell victim to eugenicists' sterilization

initiatives were women who identified as African American, Hispanic, or

Native American. As a result, the United States' Progressive-era eugenics movement is now generally associated with racist and nativist

elements, as the movement was to some extent a reaction to demographic

and population changes, as well as concerns over the economy and social

well-being, rather than scientific genetics.

History

Early proponents

The American eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of Sir Francis Galton,

which originated in the 1880s. In 1883, Sir Francis Galton first used

the word eugenics to describe scientifically, the biological improvement

of genes in human races and the concept of being "well-born".

He believed that differences in a person's ability were acquired

primarily through genetics and that eugenics could be implemented

through selective breeding in order for the human race to improve in its overall quality, therefore allowing for humans to direct their own evolution. In the US, eugenics was largely supported after the discovery of Mendel's law lead to a widespread interest in the idea of breeding for specific traits.

Galton studied the upper classes of Britain, and arrived at the

conclusion that their social positions could be attributed to a superior

genetic makeup. U.S. eugenicists tended to believe in the genetic superiority of Nordic, Germanic and Anglo-Saxon peoples, supported strict immigration and anti-miscegenation laws, and supported the forcible sterilization of the poor, disabled and "immoral."

Eugenics supporters hold signs criticizing various "genetically inferior" groups.

Wall Street, New York, c. 1915.

The American eugenics movement received extensive funding from various corporate foundations including the Carnegie Institution, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Harriman railroad fortune. In 1906 J.H. Kellogg provided funding to help found the Race Betterment Foundation in Battle Creek, Michigan. The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) was founded in Cold Spring Harbor, New York in 1911 by the renowned biologist Charles B. Davenport, using money from both the Harriman railroad fortune and the Carnegie Institution. As late as the 1920s, the ERO was one of the leading organizations in the American eugenics movement.

In years to come, the ERO collected a mass of family pedigrees and

provided training for eugenics field workers who were sent to analyze

individuals at various institutions, such as mental hospitals and

orphanage institutions, across the United States. Eugenicists such as Davenport, the psychologist Henry H. Goddard, Harry H. Laughlin, and the conservationist Madison Grant (all of whom were well-respected during their time) began to lobby for various solutions to the problem of the "unfit." Davenport favored immigration restriction and sterilization as primary methods; Goddard favored segregation in his The Kallikak Family; Grant favored all of the above and more, even entertaining the idea of extermination.

By 1910, there was a large and dynamic network of scientists,

reformers, and professionals engaged in national eugenics projects and

actively promoting eugenic legislation. The American Breeder's Association,

the first eugenic body in the U.S., expanded in 1906 to include a

specific eugenics committee under the direction of Charles B. Davenport.

The ABA was formed specifically to "investigate and report on heredity

in the human race, and emphasize the value of superior blood and the

menace to society of inferior blood." Membership included Alexander Graham Bell, Stanford president David Starr Jordan and Luther Burbank. The American Association for the Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality was one of the first organizations to begin investigating infant mortality rates in terms of eugenics. They promoted government intervention in attempts to promote the health of future citizens.

Several feminist reformers advocated an agenda of eugenic legal reform. The National Federation of Women's Clubs, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and the National League of Women Voters were among the variety of state and local feminist organization that at some point lobbied for eugenic reforms. One of the most prominent feminists to champion the eugenic agenda was Margaret Sanger, the leader of the American birth control movement and founder of Planned Parenthood.

Sanger saw birth control as a means to prevent unwanted children from

being born into a disadvantaged life, and incorporated the language of

eugenics to advance the movement.

Sanger also sought to discourage the reproduction of persons who, it

was believed, would pass on mental disease or serious physical defects. In these cases, she approved of the use of sterilization.

In Sanger's opinion, it was individual women (if able-bodied) and not

the state who should determine whether or not to have a child.

U.S.

eugenics poster advocating for the removal of genetic "defectives" such

as the insane, "feeble-minded" and criminals, and supporting the

selective breeding of "high-grade" individuals, c. 1926

In the Deep South, women's associations

played an important role in rallying support for eugenic legal reform.

Eugenicists recognized the political and social influence of southern

clubwomen in their communities, and used them to help implement eugenics

across the region. Between 1915 and 1920, federated women's clubs in every state of the Deep South had a critical role in establishing public eugenic institutions that were segregated by sex. For example, the Legislative Committee of the Florida

State Federation of Women's Clubs successfully lobbied to institute a

eugenic institution for the mentally retarded that was segregated by

sex.

Their aim was to separate mentally retarded men and women in order to

prevent them from breeding more "feebleminded" individuals.

Public acceptance in the U.S. led to various state legislatures working to establish eugenic initiatives. Beginning with Connecticut in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded" from marrying. The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was Michigan

in 1897 - although the proposed law failed to garner enough votes by

legislators to be adopted, it did set the stage for other sterilization

bills. Eight years later, Pennsylvania's state legislators passed a sterilization bill that was vetoed by the governor. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907, followed closely by Washington, California, and Connecticut in 1909. Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low (California being the sole exception) until the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell which legitimized the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for those who were seen as mentally retarded.

Immigration restrictions

In the late 19th century, many scientists, who were concerned about

the population leaning too far away from the favored "Anglo-Saxon

superiority" due to a rise in immigration from Europe, partnered with

other interest groups to implement immigration laws that could be

justified on the basis of genetics.

After the 1890 U.S. census, people began to believe that immigrants who

were of Nordic or Anglo-Saxon stock were greatly favored over Southern

and Eastern Europeans, specifically Jews who were seen by some

eugenicists, like Harry Laughlin, to be genetically inferior.

During the early 20th century as the United States and Canada began to

receive higher numbers of immigrants, influential eugenicists like Lothrop Stoddard

and Laughlin (who was appointed as an expert witness for the House

Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in 1920) presented arguments

that these immigrants would pollute the national gene pool if their

numbers went unrestricted.

In 1921, a temporary measure was passed to slowdown the open door on immigration. The Immigration Restriction League

was the first American entity to be closely associated with eugenics

and was founded in 1894 by three recent Harvard graduates. The overall

goal of the League was to prevent what they perceived as inferior races

from diluting "the superior American racial stock" (those who were of

the upper-class Anglo-Saxon heritage), and they began working to have

stricter anti-immigration laws in the United States. The League lobbied for a literacy test

for immigrants as they attempted to enter the United States, based on

the belief that literacy rates were low among "inferior races".

Eugenicists believed that immigrants were often degenerate, had low

IQs, and were afflicted with shiftlessness, alcoholism and

insubordination. According to Eugenicists, all of these problems were

transmitted through genes. Literacy test bills were vetoed by Presidents

in 1897, 1913 and 1915; eventually, President Wilson's second veto was

overruled by Congress in 1917.

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924,

eugenicists for the first time played an important role in the

Congressional debate as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior

stock" from eastern and southern Europe. The new act, inspired by the eugenic belief in the racial superiority of "old stock" white Americans as members of the "Nordic race" (a form of white supremacy), strengthened the position of existing laws prohibiting race-mixing.

Whereas Anglo-Saxon and Nordic people were seen as the most desirable

immigrants, the Chinese and Japanese were seen as the least desirable

and were largely banned from entering the U.S as a result of the

immigration act. In addition to the immigration act, eugenic considerations also lay behind the adoption of incest laws in much of the U.S. and were used to justify many anti-miscegenation laws.

Efforts to shape American families

Unfit v. fit individuals

Both class and race factored into the eugenic definitions of "fit"

and "unfit." By using intelligence testing, American eugenicists

asserted that social mobility was indicative of one's genetic fitness. This reaffirmed the existing class and racial hierarchies

and explained why the upper-to-middle class was predominantly white.

Middle-to-upper class status was a marker of "superior strains."

In contrast, eugenicists believed poverty to be a characteristic of

genetic inferiority, which meant that those deemed "unfit" were

predominantly of the lower classes.

Because class status designated some more fit than others,

eugenicists treated upper and lower-class women differently. Positive

eugenicists, who promoted procreation among the fittest in society,

encouraged middle-class women to bear more children. Between 1900 and

1960, eugenicists appealed to middle class white women to become more

"family minded," and to help better the race. To this end, eugenicists often denied middle and upper-class women sterilization and birth control. However, since poverty was associated with prostitution and "mental idiocy," women of the lower classes were the first to be deemed "unfit" and "promiscuous."

Concerns over hereditary genes

In the 19th century, based on a view of Lamarckism,

it was believed that the damage done to people by diseases could be

inherited and therefore, through eugenics, these diseases could be

eradicated. This belief was carried into the 20th century as public

health measures were taken to improve health with the hope that such

measures would result in better health of future generations.

A 1911 Carnegie Institute report explored eighteen methods for removing defective genetic attributes; the eighth method was euthanasia. Though the most commonly suggested method of euthanasia was to set up local gas chambers,

many in the eugenics movement did not believe that Americans were ready

to implement a large-scale euthanasia program, so many doctors came up

with alternative ways of subtly implementing eugenic euthanasia in

various medical institutions. For example, a mental institution in Lincoln, Illinois fed its incoming patients milk infected with tuberculosis (reasoning that genetically fit individuals would be resistant), resulting in 30–40% annual death rates. Other doctors practiced euthanasia through various forms of lethal neglect.

In the 1930s, there was a wave of portrayals of eugenic "mercy

killings" in American film, newspapers, and magazines. In 1931, the

Illinois Homeopathic Medicine Association began lobbying for the right to euthanize "imbeciles" and other defectives. A few years later, in 1938, the Euthanasia Society of America was founded.

However, despite this, euthanasia saw marginal support in the U.S.,

motivating people to turn to forced segregation and sterilization

programs as a means for keeping the "unfit" from reproducing.

Better Baby Contests

Mary deGormo, a former teacher, was the first person to combine ideas

about health and intelligence standards with competitions at state

fairs, in the form of baby contests. She developed the first such contest, the "Scientific Baby Contest" for the Louisiana State Fair in Shreveport, in 1908.

She saw these contests as a contribution to the "social efficiency"

movement, which was advocating for the standardization of all aspects of

American life as a means of increasing efficiency. DeGarmo was assisted by Doctor Jacob Bodenheimer, a pediatrician

who helped her develop grading sheets for contestants, which combined

physical measurements with standardized measurements of intelligence.

Contestants preparing for the Better Baby Contest at the 1931 Indiana State Fair.

The contest spread to other U.S. states in the early twentieth century. In Indiana, for example, Ada Estelle Schweitzer,

a eugenics advocate and director of the Indiana State Board of Health's

Division of Child and Infant Hygiene, organized and supervised the

state's Better Baby contests at the Indiana State Fair

from 1920 to 1932. It was among the fair's most popular events. During

the contest's first year at the fair, a total of 78 babies were

examined; in 1925 the total reached 885. Contestants peaked at 1,301

infants in 1930, and the following year the number of entrants was

capped at 1,200. Although the specific impact of the contests was

difficult to assess, statistics helped to support Schweitzer's claims

that the contests helped reduce infant mortality.

The intent of the contest was to educate the public about raising

healthier children as during the time period, it was approximated that

100 infants out of every 1000 births passed away prior to their first

birthday.

However, its exclusionary practices reinforced social class and racial

discrimination. In Indiana, for example, the contestants were limited to

white infants; African American and immigrant children were barred from the competition for ribbons and cash prizes. In addition, the scoring was biased toward white, middle-class babies.

The contest procedure included recording each child's health history,

as well as evaluations of each contestant's physical and mental health

and overall development using medical professionals. Using a process

similar to the one introduced at the Louisiana State Fair, and contest

guidelines that the AMA and U.S. Children's Bureau recommended, scoring

for each contestant began with 1,000 points. Deductions were made for

defects, including a child's measurements below a designated average.

The contestant with the most points was declared the winner.

Standardization

through scientific judgment was a topic that was very serious in the

eyes of the scientific community, but has often been downplayed as just a

popular fad or trend. Nevertheless, a lot of time, effort, and money

was put into these contests and their scientific backing, which would

influence cultural ideas as well as local and state government

practices.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People promoted eugenics by hosting "Better Baby" contests and the proceeds would go to its anti-lynching campaign.

Fitter Families

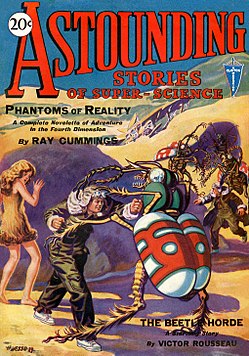

First appearing in 1920 at the Kansas Free Fair, "Fitter Families for

Future Firesides" competitions continued all the way up to World War II. Mary T. Watts and Dr. Florence Brown Sherbon, both initiators of the Better Baby Contests in Iowa, took the idea of positive eugenics for babies and combined it with a determinist concept of biology to come up with fitter family competitions.

There were several different categories that families were judged

in: size of the family, overall attractiveness, and health of the

family, all of which helped to determine the likelihood of having

healthy children. These competitions were simply a continuation of the

Better Baby contests that promoted certain physical and mental

qualities.

At the time, it was believed that certain behavioral qualities were

inherited from one's parents. This led to the addition of several

judging categories including: generosity, self-sacrificing, and quality of familial bonds. Additionally, there were negative features that were judged: selfishness, jealousy, suspiciousness, high-temperedness, and cruelty. Feeblemindedness, alcoholism, and paralysis were few among other traits that were included as physical traits to be judged when looking at family lineage.

Doctors and specialists from the community would offer their time

to judge these competitions, which were originally sponsored by the Red

Cross. The winners of these competitions were given a Bronze Medal as well as champion cups called "Capper Medals." The cups were named after then-Governor and Senator, Arthur Capper and he would present them to "Grade A individuals".

The perks of entering into the contests were that the

competitions provided a way for families to get a free health check-up

by a doctor as well as some of the pride and prestige that came from

winning the competitions.

By 1925 the Eugenics Records Office was distributing standardized

forms for judging eugenically fit families, which were used in contests

in several U.S. states.

Compulsory sterilization

In 1907, Indiana passed the first eugenics-based compulsory sterilization law in the world. Thirty U.S. states would soon follow their lead. Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1921, in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924, allowing for the compulsory sterilization of patients of state mental institutions.

The number of sterilizations performed per year increased until another Supreme Court case, Skinner v. Oklahoma,

1942, which ruled that under the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection

Clause, laws that permitted the compulsory sterilization of criminals

were unconstitutional if these laws treated similar crimes differently.

Although Skinner determined that the right to procreate was a

fundamental right under the constitution, the case did not denounce

sterilization laws as the analysis was based on the equal protection of

criminal defendants specifically, therefore leaving those seen as

'social undesirables'--the poor, the disabled, and various ethnic

groups—as targets of compulsory sterilization.

Therefore, though compulsory sterilization is now considered an abuse

of human rights, Buck v. Bell has never been overturned, and Virginia

specifically did not repeal its sterilization law until 1974.

Men and women were compulsorily sterilized for different reasons.

Men were sterilized to treat their aggression and to eliminate their

criminal behavior, while women were sterilized to control the results of

their sexuality.

Since women bore children, eugenicists held women more accountable than

men for the reproduction of the less "desirable" members of society.

Eugenicists therefore predominantly targeted women in their efforts to

regulate the birth rate, to "protect" white racial health, and weed out

the "defectives" of society.

The most significant era of eugenic sterilization

was between 1907 and 1963, when over 64,000 individuals were forcibly

sterilized under eugenic legislation in the United States.

Beginning around 1930, there was a steady increase in the percentage of

women sterilized, and in a few states only young women were sterilized.

A 1937 Fortune magazine poll found that 2/3 of respondents

supported eugenic sterilization of "mental defectives", 63% supported

sterilization of criminals, and only 15% opposed both. From 1930 to the 1960s, sterilizations were performed on many more institutionalized women than men. By 1961, 61 percent of the 62,162 total eugenic sterilizations in the United States were performed on women. A favorable report on the results of sterilization in California, the state that conducted the most sterilizations (20,000 of the 60,000 that occurred between 1909 and 1960), was published in book form by the biologist Paul Popenoe and was widely cited by the Nazi government as evidence that wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.

After World War II, eugenics and eugenic organizations began to

revise their standards of reproductive fitness to reflect contemporary

social concerns of the later half of the 20th century, notably concerns

over welfare, Mexican immigration, overpopulation, civil rights, and

sexual revolution, and gave way to what has been termed neo-eugenics.

Neo-eugenicists like Dr. Clarence Gamble, an affluent researcher at

Harvard Medical school and a founder of public birth control clinics,

revived the eugenics movement in the United States through

sterilization. Supporters of this revival of eugenic sterilizations

believed that they would bring an end to social issues such as poverty

and mental illness while also saving taxpayer money and boost the

economy.

Whereas eugenic sterilization programs before WWII were mostly

conducted on prisoners or patients in mental hospitals, after the war,

compulsory sterilizations were targeted at poor people and minorities.

As a result of these new sterilization initiatives, though most

scholars agree that there were over 64,000 known cases of eugenic

sterilization in the U.S. by 1963, no one knows for certain how many

compulsory sterilizations occurred between the late 1960s to 1970s,

though it is estimated that at least 80,000 may have been conducted.

A large number of those who were targets of coerced sterilizations in

the later half of the century were African American, Hispanic, and

Native American Women.

Eugenics, sterilization, and the African American community

African American support for eugenics and birth control (late 19th to early 20th centuries)

Early proponents of the eugenics movement did not only include

influential white Americans but also several proponent African American

intellectuals such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Thomas Wyatt Turner, and many academics at Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Hampton University.

However, unlike many white eugenicists, these black intellectuals

believed the best African Americans were as good as the best White

Americans, and "The Talented Tenth" of all races should mix. Indeed, Du Bois believed "only fit blacks should procreate to eradicate the race's heritage of moral iniquity."

With the support of leaders like Du Bois, efforts were made in

the early 20th century to control the reproduction of the country's

black population; one of the most visible initiatives was Margaret

Sanger's 1939 proposal, The Negro Project. That year, Sanger, Florence Rose, her assistant, and Mary Woodward Reinhardt, then secretary of the new Birth Control Federation of America (BCFA), drafted a report on "Birth Control and the Negro."

In this report, they stated that African Americans were the group with

"the greatest economic, health and social problems," were largely

illiterate and "still breed carelessly and disastrously," a line taken

from W.E.B. DuBois' article in the June 1932 Birth Control Review.

The Project often sought after prominent African American leaders to

spread knowledge regarding birth control and the perceived positive

effects it would have on the African American community, such as poverty

and the lack of education.

Sanger particularly sought out black ministers from the South to serve

as leaders in the Project in the hopes of countering any ideas that the

project was a strategic attempt to eradicate the black population.

However, despite Sanger's best efforts, white medical scientists took

control over the initiative, and with the Negro Project receiving praise

from white leaders and eugenicists, many of Sanger's opponents, both

during the creation of the Project and years after, saw her work as an

attempt to terminate African Americans.

Eugenics during the civil rights era

Opposition to initiatives to control reproduction within the African

American community grew in the 1960s, particularly after President Lyndon B. Johnson, in 1965, announced the establishment of federal funding of birth control used on the poor.

In the 1960, many African Americans throughout the country took the

government's decision to fund birth control clinics as an attempt to

limit the growth of the black population and along with it, the increase

political power that black Americans were fighting to acquire. Scholars have stated that African Americans' fear about their reproductive health and ability was rooted in history as under U.S. slavery, enslaved women were often coerced or forced to have children to increase a plantation owner's wealth. Therefore, many African Americans, particularly those in the Black Power Movement,

saw birth control, and federal support of the Pill, as equivalent to

black genocide, declaring it as such at the 1967 Black Power Conference.

Federal funding for birth control went alongside family planning

initiatives that were a part of state welfare programs. These

initiatives, in addition to advocating the use of the Pill, supported

sterilization as a means of curbing the number of people receiving

welfare and control the reproduction of 'unfit' women.

The 1950s and 1960s were the height of the sterilization abuse that

African American women as a group experienced at the hands of the white

medical establishment.

During this period, the sterilization of African American women largely

took place in the South and assumed two forms: the sterilization of

poor unwed black mothers, and "Mississippi appendectomies."

Under these "Mississippi appendectomies," women who went to the

hospital to give birth, or for some other medical treatment, often found

themselves incapable of having more children upon leaving the hospital

due to unnecessary hysterectomies performed on them by southern medical

students.

By the 1970s, the coerced sterilization of women of color spread from

the South to the rest of the country through federal family planning and

under the guise of voluntary contraceptive surgery as physicians began

to require their patients to sign consent forms to surgeries they did

not want or understand.

Sterilization of African American women

Though it is unknown the exact number of African American women who

were sterilized throughout the country in the 20th century, records from

a few states offer some estimates. In the state of North Carolina,

which was seen as having the most aggressive eugenics program out of the

32 states that had one, during the 45-year reign of the North Carolina Eugenics Board,

from 1929 to 1974, a disproportionate number of those who were targeted

for forced or coerced sterilization were black and female, with almost

all being poor. Of the 7,600 women who were sterilized by the state between the years of 1933 and 1973, about 5,000 were African American.

In light of this history, North Carolina became the first state to

offer compensation to surviving victims of compulsory sterilization.

Additionally, whereas African Americans made up just over 1% of

California's population, they accounted for at least 4% of the total

number of sterilization operations conducted by the state between 1909

and 1979.

Overall, according to one 1989 study, 31.6% of African American women

without a high school diploma were sterilized while only 14.5% of white

women of the same educational status were sterilized.

Sterilization abuse brought to media attention

In 1972, United States Senate

committee testimony brought to light that at least 2,000 involuntary

sterilizations had been performed on poor black women without their

consent or knowledge.

An investigation revealed that the surgeries were all performed in the

South, and were all performed on black women with multiple children who

were receiving welfare.

Testimony revealed that many of these women were threatened with an end

to their welfare benefits unless they consented to sterilization.

These surgeries were instances of sterilization abuse, a term applied

to any sterilization performed without the consent or knowledge of the

recipient, or in which the recipient is pressured into accepting the

surgery. Because the funds used to carry out the surgeries came from the

U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity,

the sterilization abuse raised suspicions, especially among members of

the black community, that "federal programs were underwriting

eugenicists who wanted to impose their views about population quality on

minorities and poor women."

Despite this investigation, it was not until 1973 that the issue

of sterilization abuse was brought to media attention. On June 14, 1973,

two black girls, Minnie Lee and Mary Alice Relf,

ages fourteen and twelve, respectively, were sterilized without their

knowledge in Alabama by the Montgomery Community Action Committee, an

OEO-financed organization. The summer of that year, the Relf girls sued the government agencies and individuals responsible for their sterilization.

As the case was being pursued, it was discovered that the girls'

mother, who could not read, unwittingly approved the operations, signing

an 'X' on the release forms; Mrs. Relf had believed that she was

signing a form authorizing her daughters to receive Depo-Provera

injections, a form of birth control. In light of the 1974 case of Relf v. Weinberger, named after Minnie Lee and Mary Alice's older sister, Katie, who had narrowly escaped also being sterilized, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) were ordered to establish new guidelines for its government sterilization policy.

By 1979, the new guidelines finally addressed the concern over informed

consent, determined that minors under the age of 21 and those with

severe mentally impairments who could not give consent would not be

sterilized, and articulated the provision that doctors could no longer

claim that a woman's refusal to be sterilized would result in her being

denied welfare benefits.

Sterilization of Latina women

The 20th century demarcated a time in which compulsory sterilization heavily navigated its way into primarily Latinx communities, against Latina women. Locations such as Puerto Rico and Los Angeles, California

were found to have had large amounts of their female population coerced

into sterilization procedures without quality and necessary informed consent nor full awareness of the procedure.

Puerto Rico

Between the span of the 1930s to the 1970s, nearly one-third of the

female population in Puerto Rico was sterilized; at the time, this was

the highest rate of sterilization in the world.

Arguments stand that the implementation of sterilization was in an

effort to rectify the country's poverty and unemployment rates, even so

that sterilization became legal in the eyes of the government in 1937. The procedure was so common that it was often referred to solely as “la operación", garnering a documentary

referenced by the same name. This intentional targeting of Latinx

communities exemplifies the strategic placement of racial eugenics in

modern history. This targeting is also inclusive of those with

disabilities and those from marginalized populations, which Puerto Rico

is not the only example of this trend.

Eugenics did not serve as the only reason for the disproportionate rates of sterilization in the Puerto Rican community. Contraceptive trials were inducted in the 1950s towards Puerto Rican women. Dr. John Rock and Dr. Gregory Pincus were the two men spearheading the human trials of oral contraceptives.

In 1954, the decision was made to conduct the clinical experiment in

Puerto Rico, citing the island's large network of birth control clinics

and lack of anti-birth control laws, which was in contrast to the United

States' thorough cultural and religious opposition to the reproductive

service.

The decision to conduct the trials in this community was also motivated

by the structural implications of supremacy and colonialism. Rock and

Pincus monopolized off of the primarily poor and uneducated background

of these women, countering that if they "could follow the Pill regimen,

then women anywhere in the world could too."

These women were purposely ill-informed of the oral contraceptives

presence; the researchers only reported that the drug, which was

administered at a much higher dosage than what birth control is

prescribed at today, was to prevent pregnancy, not that it was tied to a

clinical trial in order to jump start oral contraceptive access in

America through FDA approval.

California

In California, by the year 1964, a total of 20,108 people were

sterilized, making that the largest amount in all of the United States.

It is an important note that during this period in California's

population demographic, the total individuals sterilized was

disproportionately inclusive of Mexican, Mexican-American, and Chicana women. Andrea Estrada, a UC Santa Barbara affiliate, said:

Beginning

in 1909 and continuing for 70 years, California led the country in the

number of sterilization procedures performed on men and women, often

without their full knowledge and consent. Approximately 20,000

sterilizations took place in state institutions, comprising one-third of

the total number performed in the 32 states where such action was

legal.

Cases such as Madrigal v. Quilligan,

a class action suit regarding forced or coerced postpartum

sterilization of Latina women following cesarean sections, helped bring

to light the widespread abuse of sterilization supported by federal

funds. The case's plaintiffs were 10 sterilized women of Los Angeles County Hospital who elected to come forward with their stories. Although a grim reality, No más bebés is a documentary that offers an emotional and candid storytelling of the Madrigal v. Quilligan

case on behalf of Latina women whom were direct recipients of the

coerced sterilization of the Los Angeles' hospital. The judge's ruling

sided with the County Hospital, but an aftermath of the case resulted in

the accessibility of multiple language informed consent forms.

These stories, among many others, serve as backbones for not only the reproductive justice movement that we see today, but a better understanding and recognition of the Chicana feminism movement in contrast to white feminism's perception of reproductive rights.

Sterilization of Native American women

An

estimated 40% of Native American women (60,000-70,000 women) and 10% of

Native American men in the United States underwent sterilization in the

1970s.

A General Accounting Office (GAO) report in 1976 found that 3,406

Native American women, 3,000 of which were of childbearing age, were sterilized by the Indian Health Service (IHS) in Arizona, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and South Dakota from 1973 to 1976. The GAO report did not conclude any instances of coerced sterilization, but called for the reform of IHS and contract doctors' processes of obtaining informed consent for sterilization procedures. The IHS

informed consent processes examined by the GAO did not comply with a

1974 ruling of the U.S. District Court that "any individual

contemplating sterilization should be advised orally at the outset that

at no time could federal benefits be withdrawn because of failure to

agree to sterilization."

In examining individual cases and testimonies of Native American women, scholars have found that IHS

and contract physicians recommended sterilization to Native American

women as the appropriate form of birth control, failing to present

potential alternatives and to explain the irreversible nature of

sterilization, and threatened that refusal of the procedure would result

in the women losing their children and/or federal benefits.

Scholars also identified language barriers in informed consent

processes as the absence of interpreters for Native American women

hindered them from fully understanding the sterilization procedure and

its implications, in some cases.

Scholars have cited physicians' individual paternalism and beliefs

about the population control of poor communities and welfare recipients

and the opportunity for financial gain as possible motivations for

performing sterilizations on Native American women.

Native American women and activists mobilized in the 1970s across

the United States to combat the coerced sterilization of Native

American women and advocate for their reproductive rights, alongside

tribal sovereignty, in the Red Power movement.

Some of the most prominent activist organizations established in this

decade and active in the Red Power movement and the resistance against

coerced sterilization were the American Indian Movement (AIM), United

Native Americans, Women of all Red Nations (WARN), the International

Indian Treaty Council (IITC), and Indian Women United for Justice,

founded by Dr. Constance Redbird Pinkerton Uri, a Cherokee-Choctaw

physician. Some Native American activists have deemed the coerced sterilization of Native American women a "modern form of genocide," and view these sterilizations as a violation of the rights of tribes as sovereign nations.

Others argue that the sterilization of Native American women is

interconnected with colonialist and capitalist motives of corporations

and the federal government to acquire land and natural resources,

including oil, natural gas, and coal, currently located on Native

American reservations. Scholars and Native American activists have situated the forced

sterilizations of Native American women within broader histories of

colonialism, violations of Native American tribal sovereignty by the

federal government, including a long history of the removal of children

from Native American women and families, and population control efforts

in the United States.

The 1970s brought new federal legislation enacted by the United

States government which addressed issues of informed consent,

sterilization, and the treatment of Native American children. The U.S.

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare released new regulations in

1979 on informed consent processes for sterilization procedures,

including a longer waiting period of 30 days before the procedure, the

presentation of alternative methods of birth control to the patient, and

clear verbal affirmation that the patient's access to federal benefits

or welfare programs would not be revoked if the procedure were refused. The Indian Child Welfare Act

of 1978 officially recognized the significance and value of the

extended family in Native American culture, adopting "minimum federal

standards for the removal of Indian children to foster or adoptive

homes,"

and the central importance of the sovereign tribal governments in

decision-making processes surrounding the welfare of Native children.

Influence on Nazi Germany

After the eugenics movement was well established in the United States, it spread to Germany. California eugenicists

began producing literature promoting eugenics and sterilization and

sending it overseas to German scientists and medical professionals.

By 1933, California had subjected more people to forceful sterilization

than all other U.S. states combined. The forced sterilization program

engineered by the Nazis was partly inspired by California's.

The Rockefeller Foundation helped develop and fund various German eugenics programs, including the one that Josef Mengele worked in before he went to Auschwitz.

Upon returning from Germany in 1934, where more than 5,000 people per

month were being forcibly sterilized, the California eugenics leader C.

M. Goethe bragged to a colleague:

You

will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in

shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind

Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their

opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought ... I

want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of

your life, that you have really jolted into action a great government

of 60 million people.

Eugenics researcher Harry H. Laughlin often bragged that his Model Eugenic Sterilization laws had been implemented in the 1935 Nuremberg racial hygiene laws. In 1936, Laughlin was invited to an award ceremony at Heidelberg University

in Germany (scheduled on the anniversary of Hitler's 1934 purge of Jews

from the Heidelberg faculty), to receive an honorary doctorate for his

work on the "science of racial cleansing". Due to financial limitations,

Laughlin was unable to attend the ceremony and had to pick it up from

the Rockefeller Institute. Afterward, he proudly shared the award with

his colleagues, remarking that he felt that it symbolized the "common

understanding of German and American scientists of the nature of

eugenics."

Henry Friedlander wrote that although the German and American eugenics movements were similar, the U.S. did not follow the same slippery slope

as Nazi eugenics because American "federalism and political

heterogeneity encouraged diversity even with a single movement." In

contrast, the German eugenics movement was more centralized and had

fewer diverse ideas. Unlike the American movement, one publication and one society, the German Society for Racial Hygiene, represented all German eugenicists in the early 20th century.

After 1945, however, historians began to try to portray the U.S. eugenics movement as distinct and distant from Nazi eugenics. Jon Entine

wrote that eugenics simply means "good genes" and using it as synonym

for genocide is an "all-too-common distortion of the social history of

genetics policy in the United States." According to Entine, eugenics

developed out of the Progressive Era and not "Hitler's twisted Final Solution."

Eugenics after World War II

Genetic engineering

After Hitler's advanced idea of eugenics, the movement lost its place

in society for a bit of time. Although eugenics was not thought about

much, aspects like sterilization were still taking place, just not at

such a public level.

As technology developed, the field of genetic engineering emerged.

Instead of sterilizing people to ultimately get rid of "undesirable"

people, genetic engineering "changes or removes genes to prevent disease

or improve the body in some significant way."

Proponents of genetic engineering cite its ability to cure and

prevent life-threatening diseases. Genetic engineering began in the

1970s when scientists began to clone and alter genes. From this,

scientists were able to create life-saving health interventions such as

human insulin, the first-ever genetically-engineered drug.

Because of this development, over the years scientists were able to

create new drugs to treat devastating diseases. For example, in the

early 1990s, a group of scientists were able to use a gene-drug to treat

severe combined immunodeficiency in a young girl.

However, genetic engineering also further allows for the practice

of eliminating "undesirable traits" within humans and other organisms -

for example, with current genetic tests, parents are able to test a

fetus for any life-threatening diseases that may impact the child's life

and then choose to abort the baby. Some fear that this will could lead to ethnic cleansing, or alternative form of eugenics. The ethical implications of genetic engineering were heavily considered by scientists at the time, and the Asilomar Conference

was held in 1975 to discuss these concerns and set reasonable,

voluntary guidelines that researchers would follow while using DNA

technologies.

Compulsory sterilization prevention and continuation

The 1978 Federal Sterilization Regulations, created by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare or HEW, (now the United States Department of Health and Human Services)

outline a variety of prohibited sterilization practices that were often

used previously to coerce or force women into sterilization.

These were intended to prevent such eugenics and neo-eugenics as

resulted in the involuntary sterilization of large groups of poor and

minority women. Such practices include: not conveying to patients that

sterilization is permanent and irreversible, in their own language

(including the option to end the process or procedure at any time

without conceding any future medical attention or federal benefits, the

ability to ask any and all questions about the procedure and its

ramifications, the requirement that the consent seeker describes the

procedure fully including any and all possible discomforts and/or

side-effects and any and all benefits of sterilization); failing to

provide alternative information about methods of contraception, family

planning, or pregnancy termination that are nonpermanent and/or

irreversible (this includes abortion); conditioning receiving welfare and/or Medicaid

benefits by the individual or his/her children on the individuals

"consenting" to permanent sterilization; tying elected abortion to

compulsory sterilization (cannot receive a sought out abortion without

"consenting" to sterilization); using hysterectomy as sterilization; and subjecting minors and the mentally incompetent to sterilization.

The regulations also include an extension of the informed consent

waiting period from 72 hours to 30 days (with a maximum of 180 days

between informed consent and the sterilization procedure).

However, several studies have indicated that the forms are often

dense and complex and beyond the literacy aptitude of the average

American, and those seeking publicly funded sterilization are more

likely to possess below-average literacy skills.

High levels of misinformation concerning sterilization still exist

among individuals who have already undergone sterilization procedures,

with permanence being one of the most common gray factors.

Additionally, federal enforcement of the requirements of the 1978

Federal Sterilization Regulation is inconsistent and some of the

prohibited abuses continue to be pervasive, particularly in underfunded

hospitals and lower income patient hospitals and care centers.

The compulsory sterilization of American men and women continues

to this day. In 2013, it was reported that 148 female prisoners in two

California prisons were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a supposedly

voluntary program, but it was determined that the prisoners did not

give consent to the procedures.

In September 2014, California enacted Bill SB1135 that bans

sterilization in correctional facilities, unless the procedure is

required to save an inmate's life.