Modern

humans (

Homo sapiens or

Homo sapiens sapiens) are the only

extant members of the

hominin clade, a

branch of

great apes characterized by

erect posture and

bipedal locomotion;

manual dexterity and increased

tool use; and a general trend toward larger, more complex

brains and

societies.

[3][4] Early hominids, such as the

australopithecines whose brains and anatomy are in many ways more similar to non-human apes, are less often thought of or referred to as "human" than hominids of the

genus Homo.

[5] Some of the latter

used fire,

occupied much of Eurasia, and gave rise to

[6][7] anatomically modern Homo sapiens in

Africa about 200,000 years ago. They began to exhibit evidence of

behavioral modernity around 50,000 years ago, and migrated in successive waves to occupy

[8] all but the smallest, driest, and coldest lands. In the last 100 years, this has extended to permanently manned bases

in Antarctica, on

offshore platforms, and

orbiting the Earth. The spread of humans and

their large and increasing population has had a profound

impact on large areas of the environment and millions of native species worldwide. Advantages that explain this evolutionary success include a relatively

larger brain with a particularly well-developed

neocortex,

prefrontal cortex and

temporal lobes, which enable high levels of abstract

reasoning,

language,

problem solving,

sociality, and

culture through social learning. Humans use

tools to a much higher degree than any other animal, are the only extant species known to build

fires and

cook their food, as well as the only extant species to

clothe themselves and create and use numerous other

technologies and

arts.

Humans are uniquely adept at utilizing systems of symbolic communication such as language and art for self-expression, the exchange of ideas, and organization. Humans create complex

social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from

families and

kinship networks to

states.

Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety of values,

[9] social norms, and

rituals, which together form the basis of human society. The human desire to understand and influence their environment, and explain and manipulate phenomena, has been the foundation for the development of

science,

philosophy,

mythology, and

religion. The scientific study of humans is the discipline of

anthropology.

Humans began to practice

sedentary agriculture about 12,000 years ago, domesticating plants and animals, thus allowing for the growth of

civilization. Humans subsequently established various forms of government, religion, and culture around the world, unifying people within a region and leading to the development of states and empires.

The rapid advancement of scientific and medical understanding in the 19th and 20th centuries led to the development of fuel-driven technologies and improved health, causing the human population to rise exponentially. By 2014 the global human

population was estimated to be around 7.2 billion.

[10][11]

Etymology and definition

In common usage, the word "human" generally refers to the only extant species of the genus

Homo — anatomically and behaviorally modern

Homo sapiens. Its usage often designates differences between the species as a whole and any other nature or entity.

In scientific terms, the definition of "human" has changed with the discovery and study of the fossil ancestors of modern humans. The previously clear boundary between human and ape blurred, resulting in "Homo" referring to "human" now encompassing multiple

species. There is also a distinction between

anatomically modern humans and

Archaic Homo sapiens, the earliest fossil members of the species, which are classified as a

subspecies of

Homo sapiens, e.g.

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

The English adjective

human is a

Middle English loanword from

Old French humain, ultimately from

Latin hūmānus, the adjective form of

homō "man". The word's use as a noun (with a plural:

humans) dates to the 16th century.

[12] The native English term

man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for

humanity), and could formerly refer to specific individuals of either sex, though this latter use is now obsolete.

[13] Generic uses of the term "man" are declining, in favor of reserving it for referring specifically to adult males. The word is from

Proto-Germanic mannaz, from a

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root

man-.

The species

binomial Homo sapiens was coined by

Carl Linnaeus in his 18th century work

Systema Naturae, and he himself is the

lectotype specimen.

[14] The

generic name Homo is a learned 18th century derivation from Latin

homō "man", ultimately "earthly being" (

Old Latin hemō, a

cognate to Old English

guma "man", from

PIE dʰǵʰemon-, meaning "earth" or "ground").

[15] The species-name

sapiens means "wise" or "sapient". Note that the Latin word

homo refers to humans of either gender, and that

sapiens is the singular form (while there is no word

sapien).

History

Evolution and range

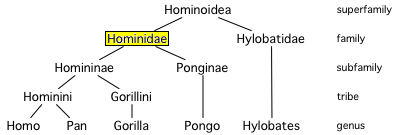

The genus

Homo diverged from other

hominins in Africa, after the human clade split from the

chimpanzee lineage of the

hominids (great ape) branch of the

primates. Modern humans, defined as the species

Homo sapiens or specifically to the single extant

subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in

Eurasia 125,000–60,000 years ago,

[16][17] Australia around 40,000 years ago, the

Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as

Hawaii,

Easter Island,

Madagascar, and

New Zealand between the years 300 and 1280.

[18][19]

Evidence from molecular biology

The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees (genus

Pan) and gorillas (genus

Gorilla).

[20] With the

sequencing of both the human and chimpanzee genome, current estimates of similarity between human and chimpanzee DNA

sequences range between 95% and 99%.

[20][21][22] By using the technique called a

molecular clock which estimates the time required for the number of divergent mutations to accumulate between two lineages, the approximate date for the split between lineages can be calculated. The gibbons (

Hylobatidae) and

orangutans (genus

Pongo) were the first groups to split from the

line leading to the humans, then

gorillas (genus

Gorilla) followed by the

chimpanzees (genus

Pan). The splitting date between human and chimpanzee lineages is placed around 4–8 million years ago during the late

Miocene epoch.

[23][24][25]

Evidence from the fossil record

There is little fossil evidence for the divergence of the gorilla, chimpanzee and hominin lineages.

[26][27] The earliest fossils that have been proposed as members of the hominin lineage are

Sahelanthropus tchadensis dating from

7 million years ago, and

Orrorin tugenensis dating from

5.7 million years ago and

Ardipithecus kadabba dating to

5.6 million years ago. Each of these has been argued to be a

bipedal ancestor of later hominins, but in each case the claims have been contested. It is also possible that either of these species is an ancestor of another branch of African apes, or that they represent a shared ancestor between hominins and other Hominoidea. The question of the relation between these early fossil species and the hominin lineage is still to be resolved. From these early species the

australopithecines arose around

4 million years ago, and diverged into

robust (also called

Paranthropus) and

gracile branches, one of which (possibly

A. garhi) went on to become ancestors of the genus

Homo.

The earliest members of the genus

Homo are

Homo habilis which evolved around

2.8 million years ago.

[28] Homo habilis is the first species for which there is clear evidence of the use of

stone tools. The brains of these early hominins were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, and their main adaptation was bipedalism as an adaptation to terrestrial living. During the next million years a process of

encephalization began, and with the arrival of

Homo erectus in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled.

Homo erectus were the first of the hominina to leave Africa, and these species spread through Africa, Asia, and Europe between

1.3 to 1.8 million years ago. One population of

H. erectus, also sometimes classified as a separate species

Homo ergaster, stayed in Africa and evolved into

Homo sapiens. It is believed that these species were the first to use fire and complex tools. The earliest transitional fossils between

H. ergaster/erectus and

archaic humans are from Africa such as

Homo rhodesiensis, but seemingly transitional forms are also found at

Dmanisi,

Georgia. These descendants of African

H. erectus spread through Eurasia from ca. 500,000 years ago evolving into

H. antecessor,

H. heidelbergensis and

H. neanderthalensis. The earliest fossils of

anatomically modern humans are from the

Middle Paleolithic, about 200,000 years ago such as the

Omo remains of Ethiopia and the fossils of Herto sometimes classified as

Homo sapiens idaltu.

[29] Later fossils of archaic

Homo sapiens from

Skhul in Israel and Southern Europe begin around 90,000 years ago.

[30]

Anatomical adaptations

Reconstruction of

Homo habilis, the earliest known species of the genus

Homo and the first human ancestor to use stone tools

Human evolution is characterized by a number of

morphological,

developmental,

physiological, and

behavioral changes that have taken place since the split between the

last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. The most significant of these adaptations are 1. bipedalism, 2. increased brain size, 3. lengthened

ontogeny (gestation and infancy), 4. decreased

sexual dimorphism. The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate.

[31] Other significant morphological changes included the evolution of a

power and precision grip, a change first occurring in

H. erectus.

[32]

Bipedalism is the basic adaption of the hominin line, and it is considered the main cause behind a suite of

skeletal changes shared by all bipedal hominins. The earliest bipedal

hominin is considered to be either

Sahelanthropus[33] or

Orrorin, with

Ardipithecus, a full bipedal, coming somewhat later. The knuckle walkers, the

gorilla and

chimpanzee, diverged around the same time, and either

Sahelanthropus or

Orrorin may be humans' last shared ancestor with those animals. The early bipedals eventually evolved into the

australopithecines and later the genus

Homo. There are several theories of the adaptational value of bipedalism. It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed up the hands for reaching and carrying food, because it saved energy during locomotion, because it enabled long distance running and hunting, or as a strategy for avoiding hyperthermia by reducing the surface exposed to direct sun.

The human species developed a much larger brain than that of other primates – typically 1,330

cc in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.

[34] The pattern of

encephalization started with

Homo habilis which at approximately 600 cc had a brain slightly larger than chimpanzees, and continued with

Homo erectus (800–1100 cc), and reached a maximum in Neanderthals with an average size of 1200-1900cc, larger even than

Homo sapiens (but less

encephalized).

[35] The pattern of human postnatal

brain growth differs from that of other apes (

heterochrony), and allows for extended periods of

social learning and

language acquisition in juvenile

humans. However, the differences between the structure of

human brains and those of other apes may be even more significant than differences in size.

[36][37][38][39] The increase in volume over time has affected different areas within the brain unequally – the

temporal lobes, which contain centers for language processing have increased disproportionately, as has the

prefrontal cortex which has been related to complex decision making and moderating social behavior.

[34] Encephalization has been tied to an increasing emphasis on meat in the diet,

[40][41] or with the development of cooking,

[42] and it has been proposed that intelligence increased as a response to an increased necessity for

solving social problems as human society became more complex.

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is primarily visible in the reduction of the male

canine tooth relative to other ape species (except

gibbons). Another important physiological change related to sexuality in humans was the evolution of

hidden estrus. Humans are the only ape in which the female is fertile year round, and in which no special signals of fertility are produced by the body (such as

genital swelling during estrus). Nonetheless humans retain a degree of sexual dimorphism in the distribution of body hair and subcutaneous fat, and in the overall size, males being around 25% larger than females. These changes taken together have been interpreted as a result of an increased emphasis on

pair bonding as a possible solution to the requirement for increased parental investment due to the prolonged infancy of offspring.

Rise of Homo sapiens

By the beginning of the

Upper Paleolithic period (50,000

BP), full

behavioral modernity, including

language,

music and other

cultural universals had developed.

[43][44] As modern humans spread out from Africa they encountered other hominids such as

Homo neanderthalensis and the so-called

Denisovans. The nature of interaction between early humans and these sister species has been a long-standing source of controversy, the question being whether humans replaced these earlier species or whether they were in fact similar enough to interbreed, in which case these earlier populations may have contributed genetic material to modern humans.

[45] Recent studies of the human and Neanderthal genomes suggest

gene flow between archaic

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and Denisovans.

[46][47][48]

This dispersal

out of Africa is estimated to have begun about 70,000 years BP from northeast Africa. Current evidence suggests that there was only one such dispersal and that it only involved a few hundred individuals. The vast majority of humans stayed in Africa and adapted to a diverse array of environments.

[49] Modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing earlier hominins (either through competition or

hybridization). They inhabited

Eurasia and

Oceania by 40,000 years BP, and the Americas at least 14,500 years BP.

[50][51]

Transition to civilization

Until c. 10,000 years ago, humans lived as

hunter-gatherers. They generally lived in small nomadic groups known as

band societies. The advent of agriculture prompted the

Neolithic Revolution, when access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent

human settlements, the

domestication of animals and the

use of metal tools for the first time in history. Agriculture encouraged

trade and cooperation, and led to complex society. Because of the significance of this date for human society, it is the epoch of the

Holocene calendar or Human Era.

[citation needed]

About 6,000 years ago, the first proto-states developed in

Mesopotamia,

Egypt's

Nile Valley and the

Indus Valley. Military forces were formed for protection, and government bureaucracies for administration. States cooperated and competed for resources, in some cases waging wars. Around 2,000–3,000 years ago, some states, such as

Persia,

India,

China,

Rome, and

Greece, developed through conquest into the first expansive

empires.

Ancient Greece was the seminal civilization that laid the foundations of

Western culture, being the birthplace of Western

philosophy,

democracy, major scientific and mathematical advances, the

Olympic Games,

Western literature and

historiography, as well as Western

drama, including both

tragedy and

comedy.

[52] Influential religions, such as

Judaism, originating in

West Asia, and

Hinduism, originating in South Asia, also rose to prominence at this time.

The late

Middle Ages saw the rise of revolutionary ideas and technologies. In China, an advanced and urbanized society promoted innovations and sciences, such as

printing and

seed drilling. In India, major advancements were made in mathematics, philosophy, religion and

metallurgy. The

Islamic Golden Age saw advancements in mathematics and astronomy in Muslim empires.

[53] In Europe, the rediscovery of

classical learning and inventions such as the

printing press led to the

Renaissance in the 14th and 15th centuries. Over the next 500 years,

exploration and

colonialism brought great parts of the world under European control, leading to later struggles for independence. The

Scientific Revolution in the 17th century and the

Industrial Revolution in the 18th–19th centuries promoted major innovations in transport, such as the railway and automobile;

energy development, such as coal and electricity; and government, such as

representative democracy and

Communism.

With the advent of the

Information Age at the end of the 20th century, modern humans live in a world that has become increasingly

globalized and interconnected. As of 2010, almost 2 billion humans are able to communicate with each other via the

Internet,

[54] and 3.3 billion by

mobile phone subscriptions.

[55]

Although interconnection between humans has encouraged the growth of

science,

art,

discussion, and

technology, it has also led to culture clashes and the development and use of

weapons of mass destruction. Human civilization has led to

environmental destruction and

pollution significantly contributing to the ongoing

mass extinction of other forms of life called the

Holocene extinction event,

[56] which may be further accelerated by

global warming in the future.

[57]

Habitat and population

The

Earth, as seen from

space in October 2000, showing the extent of human occupation of the planet. The bright lights signify both the most densely inhabited areas and ones financially capable of illuminating those areas.

Early human settlements were dependent on proximity to

water and, depending on the

lifestyle, other

natural resources used for

subsistence, such as populations of animal prey for

hunting and

arable land for growing crops and grazing

livestock. But humans have a great capacity for altering their

habitats by means of technology, through

irrigation,

urban planning,

construction,

transport,

manufacturing goods,

deforestation and

desertification.

Deliberate habitat alteration is often done with the goals of increasing material

wealth, increasing

thermal comfort, improving the amount of food available, improving

aesthetics, or improving ease of access to resources or other human settlements. With the advent of large-scale trade and

transport infrastructure, proximity to these resources has become unnecessary, and in many places, these factors are no longer a driving force behind the growth and decline of a population. Nonetheless, the manner in which a habitat is altered is often a major determinant in population change.

Technology has allowed humans to colonize all of the continents and adapt to virtually all climates. Within the last century, humans have explored

Antarctica, the ocean depths, and

outer space, although large-scale colonization of these environments is not yet feasible. With a population of over seven billion, humans are among the most numerous of the large mammals. Most humans (61%) live in Asia. The remainder live in the Americas (14%), Africa (14%), Europe (11%), and Oceania (0.5%).

[citation needed]

Human habitation within

closed ecological systems in hostile environments, such as Antarctica and outer space, is expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Life in space has been very sporadic, with no more than thirteen humans in space at any given time.

[58] Between 1969 and 1972, two humans at a time spent brief intervals on the

Moon. As of March 2015, no other celestial body has been visited by humans, although there has been a continuous human presence in space since the launch of the initial crew to inhabit the

International Space Station on October 31, 2000.

[59] However, other celestial bodies have been visited by human-made objects.

Since 1800, the

human population has increased from one billion

[60] to over seven billion,

[61] In 2004, some 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people (39.7%) lived in

urban areas. In February 2008, the U.N. estimated that half the world's population would live in

urban areas by the end of the year.

[62] Problems for humans living in

cities include various forms of pollution and

crime,

[63] especially in inner city and suburban

slums. Both overall population numbers and the proportion residing in cities are expected to increase significantly in the coming decades.

[64]

Humans have had a dramatic effect on the

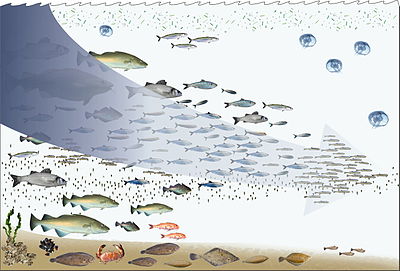

environment. Humans are

apex predators, being rarely preyed upon by other species.

[65] Currently, through land development, combustion of

fossil fuels, and pollution, humans are thought to be the main contributor to global

climate change.

[66] If this continues at its current rate it is predicted that climate change will wipe out half of all plant and animal species over the next century.

[67][68]

Biology

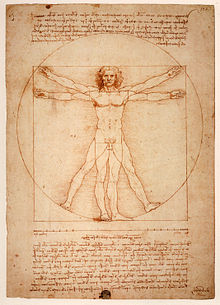

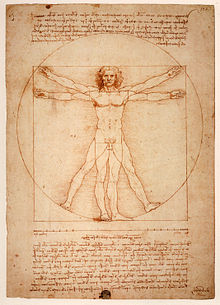

Vitruvian Man,

Leonardo da Vinci's image is often used as an implied symbol of the essential symmetry of the human body, and by extension, of the universe as a whole.

Anatomy and physiology

Most aspects of human physiology are closely

homologous to corresponding aspects of

animal physiology. The human body consists of the

legs, the

torso, the

arms, the

neck, and the

head. An

adult human body consists of about 100 trillion (10

14)

cells. The most commonly defined

body systems in humans are the

nervous, the

cardiovascular, the

circulatory, the

digestive, the

endocrine, the

immune, the

integumentary, the

lymphatic, the

muscoskeletal, the

reproductive, the

respiratory, and the

urinary system.

[69][70]

Humans, like most of the other

apes, lack external

tails, have several

blood type systems, have

opposable thumbs, and are

sexually dimorphic. The comparatively minor anatomical differences between humans and

chimpanzees are a result of human

bipedalism. As a result, humans are slower over short distances, but are among the best long-distance runners in the animal kingdom.

[71][72] Humans' thinner body hair and more productive

sweat glands help avoid

heat exhaustion while running for long distances.

[73]

As a consequence of bipedalism, human females have narrower

birth canals. The construction of the

human pelvis differs from other

primates, as do the

toes. A trade-off for these advantages of the modern human pelvis is that

childbirth is more difficult and dangerous than in most

mammals, especially given the larger head size of human

babies compared to other primates. This means that human babies must turn around as they pass through the birth canal, which other primates do not do, and it makes humans the only species where females require help from their conspecifics

[clarification needed] to reduce the risks of birthing. As a partial

evolutionary solution, human fetuses are born less developed and more vulnerable. Chimpanzee babies are cognitively more developed than human babies until the age of six months, when the rapid development of human brains surpasses chimpanzees. Another difference between women and chimpanzee females is that women go through the

menopause and become

unfertile decades before the end of their lives. All species of non-human apes are capable of giving birth until

death. Menopause probably developed as it has provided an evolutionary advantage (more caring time) to young relatives.

[72]

Apart from bipedalism, humans differ from chimpanzees mostly in

smelling,

hearing,

digesting proteins,

brain size, and the ability of

language. Humans

brains are about three times bigger than in chimpanzees. More importantly, the brain to body ratio is much higher in humans than in chimpanzees, and humans have a significantly more developed

cerebral cortex, with a larger number of

neurons. The mental abilities of humans are remarkable compared to other apes. Humans' ability of

speech is unique among primates. Humans are able to create new and complex

ideas, and to develop

technology, which is unprecedented among other

organisms on

Earth.

[72]

It is estimated that the worldwide average height for an adult human male is about 172 cm, while the worldwide average height for adult human females is about 158 cm.

[74] Shrinkage of stature may begin in middle age in some individuals, but tends to be universal

[clarification needed] in the extremely

aged.

[75] Through history human populations have universally become taller, probably as a consequence of better

nutrition,

healthcare, and living conditions.

[76]

The average

mass of an adult human is 54–64 kg (120–140 lbs) for females and 76–83 kg (168–183 lbs) for males.

[77] Like many other conditions, body weight and body type is influenced by both genetic susceptibility and environment and varies greatly among individuals. (see

obesity)

[78][79]

Although humans appear hairless compared to other primates, with notable

hair growth occurring chiefly on the top of the head, underarms and pubic area, the average human has more

hair follicles on his or her body than the average chimpanzee. The main distinction is that human hairs are shorter, finer, and less heavily pigmented than the average chimpanzee's, thus making them harder to see.

[80] Humans have about 2 million sweat glands spread over their entire bodies, many more than chimpanzees, whose sweat glands are scarce and are mainly located on the palm of the hand and on the soles of the feet.

[81]

The

dental formula of humans is:

2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Humans have proportionately shorter

palates and much smaller

teeth than other primates. They are the only primates to have short, relatively flush

canine teeth. Humans have characteristically crowded teeth, with gaps from lost teeth usually closing up quickly in young individuals. Humans are gradually losing their

wisdom teeth, with some individuals having them congenitally absent.

[82]

Genetics

A graphical representation of the ideal human

karyotype, including both the male and female variant of the sex chromosome (number 23).

Like all mammals, humans are a

diploid eukaryotic species. Each

somatic cell has two sets of 23

chromosomes, each set received from one parent;

gametes have only one set of chromosomes, which is a mixture of the two parental sets. Among the 23 pairs of chromosomes there are 22 pairs of

autosomes and one pair of

sex chromosomes. Like other mammals, humans have an

XY sex-determination system, so that

females have the sex chromosomes XX and

males have XY.

One

human genome was sequenced in full in 2003, and currently efforts are being made to achieve a sample of the genetic diversity of the species (see

International HapMap Project). By present estimates, humans have approximately 22,000 genes.

[83] The variation in human DNA is very small compared to other species, possibly suggesting a

population bottleneck during the

Late Pleistocene (around 100,000 years ago), in which the human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs.

[84][85] Nucleotide diversity is based on single mutations called

single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The nucleotide diversity between humans is about 0.1%, i.e. 1 difference per 1,000

base pairs.

[86][87] A difference of 1 in 1,000

nucleotides between two humans chosen at random amounts to about 3 million nucleotide differences, since the human genome has about 3 billion nucleotides. Most of these

single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are

neutral but some (about 3 to 5%) are functional and influence

phenotypic differences between humans through

alleles.

By comparing the parts of the genome that are not under natural selection and which therefore accumulate mutations at a fairly steady rate, it is possible to reconstruct a genetic tree incorporating the entire human species since the last shared ancestor. Each time a certain mutation (SNP) appears in an individual and is passed on to his or her descendants, a

haplogroup is formed including all of the descendants of the individual who will also carry that mutation. By comparing

mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from the mother, geneticists have concluded that the last female common ancestor whose genetic marker is found in all modern humans, the so-called

mitochondrial Eve, must have lived around 200,000 years ago.

Human accelerated regions, first described in August 2006,

[88][89] are a set of 49 segments of the

human genome that are conserved throughout

vertebrate evolution but are strikingly different in humans. They are named according to their degree of difference between humans and their nearest animal relative (

chimpanzees) (HAR1 showing the largest degree of human-chimpanzee differences). Found by scanning through genomic databases of multiple species, some of these highly

mutated areas may contribute to human-specific traits.

The forces of

natural selection have continued to operate on human populations, with evidence that certain regions of the

genome display

directional selection in the past 15,000 years.

[90]

Life cycle

As with other mammals,

human reproduction takes place as

internal fertilization by

sexual intercourse. During this process, the male inserts his

erect penis into the female's

vagina and

ejaculates semen, which contains sperm. The sperm travels through the vagina and cervix into the uterus or Fallopian tubes for

fertilization of the ovum. Upon fertilization and

implantation, gestation then occurs within the female's

uterus.

The

zygote divides inside the female's uterus to become an

embryo, which over a period of 38 weeks (9 months) of

gestation becomes a

fetus. After this span of time, the fully grown fetus is

birthed from the woman's body and breathes independently as an infant for the first time. At this point, most modern cultures recognize the baby as a person entitled to the full protection of the law, though some jurisdictions extend various levels of

personhood earlier to human fetuses while they remain in the uterus.

Compared with other species, human childbirth is dangerous. Painful labors lasting 24 hours or more are not uncommon and sometimes lead to the death of the mother, the child or both.

[91] This is because of both the relatively large fetal head circumference and the mother's relatively narrow

pelvis.

[92][93] The chances of a successful labor increased significantly during the 20th century in wealthier countries with the advent of new medical technologies. In contrast, pregnancy and

natural childbirth remain hazardous ordeals in developing regions of the world, with

maternal death rates approximately 100 times greater than in developed countries.

[94]

In developed countries, infants are typically 3–4 kg (6–9 pounds) in weight and 50–60 cm (20–24 inches) in height at birth.

[95][not in citation given] However, low

birth weight is common in developing countries, and contributes to the high levels of

infant mortality in these regions.

[96] Helpless at birth, humans continue to grow for some years, typically reaching

sexual maturity at 12 to 15 years of age. Females continue to develop physically until around the age of 18, whereas male development continues until around age 21. The

human life span can be split into a number of stages: infancy,

childhood,

adolescence,

young adulthood,

adulthood and

old age. The lengths of these stages, however, have varied across cultures and time periods. Compared to other primates, humans experience an unusually rapid growth spurt during adolescence, where the body grows 25% in size. Chimpanzees, for example, grow only 14%, with no pronounced spurt.

[97] The presence of the growth spurt is probably necessary to keep children physically small until they are psychologically mature. Humans are one of the few species in which females undergo

menopause. It has been proposed that menopause increases a woman's overall reproductive success by allowing her to invest more time and resources in her existing offspring and/or their children (the

grandmother hypothesis), rather than by continuing to bear children into old age.

[98][99]

For various reasons, including biological/genetic causes,

[100] women live on average about four years longer than men — as of 2013 the global average

life expectancy at birth of a girl is estimated at 70.2 years compared to 66.1 for a boy.

[101] There are significant geographical variations in human life expectancy, mostly correlated with economic development — for example life expectancy at birth in

Hong Kong is 84.8 years for girls and 78.9 for boys, while in

Swaziland, primarily because of

AIDS, it is 31.3 years for both sexes.

[102] The developed world is generally aging, with the median age around 40 years. In the

developing world the median age is between 15 and 20 years. While one in five Europeans is 60 years of age or older, only one in twenty Africans is 60 years of age or older.

[103] The number of

centenarians (humans of age 100 years or older) in the world was estimated by the

United Nations at 210,000 in 2002.

[104] At least one person,

Jeanne Calment, is known to have reached the age of 122 years;

[105] higher ages have been claimed but they are not well substantiated.

Diet

Humans are

omnivorous, capable of consuming a wide variety of plant and animal material.

[106][107] Varying with available food sources in regions of habitation, and also varying with cultural and religious norms, human groups have adopted a range of diets, from purely

vegetarian to primarily

carnivorous. In some cases, dietary restrictions in humans can lead to

deficiency diseases; however, stable human groups have adapted to many dietary patterns through both genetic specialization and cultural conventions to use nutritionally balanced food sources.

[108] The human diet is prominently reflected in human culture, and has led to the development of

food science.

Until the development of agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago,

Homo sapiens employed a hunter-gatherer method as their sole means of food collection. This involved combining stationary food sources (such as fruits, grains, tubers, and mushrooms, insect larvae and aquatic mollusks) with

wild game, which must be hunted and killed in order to be consumed.

[109] It has been proposed that humans have used fire to prepare and

cook food since the time of

Homo erectus.

[110] Around ten thousand years ago,

humans developed agriculture,

[111] which substantially altered their diet. This change in diet may also have altered human biology; with the spread of

dairy farming providing a new and rich source of food, leading to the evolution of the ability to digest

lactose in some adults.

[112][113] Agriculture led to increased populations, the development of cities, and because of increased population density, the wider spread of

infectious diseases. The types of food consumed, and the way in which they are prepared, has varied widely by time, location, and culture.

In general, humans can survive for two to eight weeks without food, depending on stored body fat. Survival without water is usually limited to three or four days. About 36 million humans die every year from causes directly or indirectly related to hunger.

[114] Childhood malnutrition is also common and contributes to the

global burden of disease.

[115] However global food distribution is not even, and

obesity among some human populations has increased rapidly, leading to health complications and increased mortality in some

developed, and a few

developing countries. Worldwide over one billion people are obese,

[116] while in the United States 35% of people are obese, leading to this being described as an "

obesity epidemic".

[117] Obesity is caused by consuming more

calories than are expended, so excessive weight gain is usually caused by a combination of an energy-dense high fat diet and insufficient

exercise.

[116]

Biological variation

People in warm climates are often relatively slender, tall and dark skinned, such as these

Maasai men from

Kenya.

People in cold climates tend to be relatively short, heavily built and fair skinned such as these

Inuit women from

Canada.

Young Russian peasant women in front of traditional wooden house, in a rural area along the Sheksna River near the small town of Kirillov. Early color photograph from Russia, created by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii as part of his work to document the Russian Empire from 1909 to 1915.

No two humans – not even

monozygotic twins – are genetically identical.

Genes and

environment influence human biological variation from visible characteristics to physiology to disease susceptibly to mental abilities. The exact influence of

genes and environment on certain traits is not well understood.

[118][119]

Most current

genetic and

archaeological evidence supports a recent single

origin of modern humans in

East Africa,

[120] with first migrations placed at 60,000 years ago. Compared to the

great apes,

human gene sequences – even among

African populations – are

remarkably homogeneous.

[121] On average, genetic similarity between any two humans is 99.9%.

[122][123] There is about 2–3 times more genetic diversity within the wild chimpanzee population on a single hillside in

Gombe, than in the entire

human gene pool.

[124][125][126][127]

The human body's ability to

adapt to different environmental stresses is remarkable, allowing humans to acclimatize to a wide variety of

temperatures,

humidity, and

altitudes. As a result, humans are a cosmopolitan species found in almost all regions of the world, including

tropical rainforests,

arid desert, extremely cold

arctic regions, and heavily polluted

cities. Most other species are confined to a few geographical areas by their limited adaptability.

[128]

There is biological variation in the human species — with traits such as

blood type,

cranial features,

eye color,

hair color and type,

height and

build, and

skin color varying across the globe. Human body types vary substantially. The typical height of an adult human is between 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) to 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in), although this varies significantly depending, among other things, on

sex and

ethnic origin.

[129][130] Body size is partly determined by genes and is also significantly influenced by environmental factors such as

diet,

exercise, and

sleep patterns, especially as an influence in

childhood. Adult height for each sex in a particular ethnic group approximately follows a

normal distribution. Those aspects of genetic variation that give clues to human evolutionary history, or are relevant to medical research, have received particular attention. For example the genes that allow adult humans to

digest lactose are present in high frequencies in populations that have long histories of cattle domestication, suggesting natural selection having favored that gene in populations that depend on

cow milk. Some hereditary diseases such as

sickle cell anemia are frequent in populations where

malaria has been endemic throughout history — it is believed that the same gene gives increased resistance to malaria among those who are unaffected carriers of the gene.

Similarly, populations that have for a long time inhabited specific climates, such as arctic or tropical regions or high altitudes, tend to have developed specific phenotypes that are beneficial for conserving energy in those environments —

short stature and stocky build in cold regions, tall and lanky in hot regions, and with high lung capacities at high altitudes. Similarly, skin color varies

clinally with darker skin around the equator — where the added protection from the sun's ultraviolet radiation is thought to give an evolutionary advantage — and lighter skin tones closer to the poles.

[131][132][133][134]

The hue of human skin and hair is determined by the presence of

pigments called

melanins. Human skin color can range from

darkest brown to

lightest peach, or even nearly white or colorless in cases of

albinism.

[127] Human hair ranges in color from

white to

red to

blond to

brown to

black, which is most frequent.

[135] Hair color depends on the amount of melanin (an effective sun blocking pigment) in the

skin and hair, with hair melanin concentrations in hair fading with increased age, leading to

grey or even white hair. Most researchers believe that skin darkening is an adaptation that evolved as protection against ultraviolet solar radiation, which also helps balancing

folate, which is destroyed by

ultraviolet radiation. Light skin pigmentation protects against depletion of

vitamin D, which requires

sunlight to make.

[136] Skin pigmentation of contemporary humans is clinally distributed across the planet, and in general correlates with the level of ultraviolet radiation in a particular geographic area. Human skin also has a capacity to darken (tan) in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

[137][138][139]

Structure of variation

The ancestors of

Native Americans, such as this

Yanomami woman, crossed into the Americas from Northeast Asia, and genetic and linguistic evidence links them to North Asian populations, particularly those of

East Siberia.

[140]

An older adult human male Caucasoid in Paris - playing chess at the Jardins du Luxembourg.

Within the human species, the greatest degree of genetic

variation exists between males and females. While the

nucleotide genetic variation of individuals of the same sex across global populations is no greater than 0.1%, the genetic difference between

males and

females is between 1% and 2%. Although different in nature

[clarification needed], this approaches the genetic differentiation between men and male chimpanzees or women and female chimpanzees.

The genetic difference between sexes contributes to anatomical, hormonal, neural, and physiological differences between men and women, although the exact degree and nature of social and environmental influences on sexes are not completely understood. Males on average are 15% heavier and 15 cm taller than females. There is a difference between body types, body organs and systems, hormonal levels, sensory systems, and muscle mass between sexes. On average, there is a difference of about 40–50% in upper body strength and 20–30% in lower body strength between men and women. Women generally have a higher

body fat percentage than men. Women have

lighter skin than men of the same population; this has been explained by a higher need for vitamin D (which is synthesized by sunlight) in females during

pregnancy and

lactation. As there are chromosomal differences between females and males, some X and Y chromosome related conditions and

disorders only affect either men or women. Other conditional differences between males and females are not related to sex chromosomes. Even after allowing for body weight and volume, the male

voice is usually an

octave deeper than females'. Women have a

longer life span in almost every population around the world.

[141][142][143][144][145][146][147][148][149]

Males typically have larger

tracheae and branching

bronchi, with about 30% greater

lung volume per unit

body mass. They have larger

hearts, 10% higher

red blood cell count, and higher

hemoglobin, hence greater oxygen-carrying capacity. They also have higher circulating

clotting factors (

vitamin K, pro

thrombin and

platelets). These differences lead to faster healing of

wounds and higher peripheral pain tolerance.

[150] Females typically have more

white blood cells (stored and circulating), more

granulocytes and B and T

lymphocytes. Additionally, they produce more

antibodies at a faster rate than males. Hence they develop fewer

infectious diseases and these continue for shorter periods.

[150] Ethologists argue that females, interacting with other females and multiple offspring in social groups, have experienced such traits as a

selective advantage.

[151][152][153][154][155] According to Daly and Wilson, "The sexes differ more in human beings than in

monogamous mammals, but much less than in extremely

polygamous mammals."

[156] But given that

sexual dimorphism in the closest relatives of humans is much greater than among humans, the human clade must be considered to be characterized by decreasing sexual dimorphism, probably due to less competitive mating patterns. One proposed explanation is that human sexuality has developed more in common with its close relative the

bonobo, which exhibits similar sexual dimorphism, is

polygynandrous and uses

recreational sex to reinforce social bonds and reduce aggression.

[157]

Humans of the same sex are 99.9% genetically identical. There is extremely little variation between human geographical populations, and most of the variation that does occur is at the personal level within local areas, and not between populations.

[127][158][159] Of the 0.1% of human genetic differentiation, 85% exists within any randomly chosen local population, be they Italians, Koreans, or Kurds. Two randomly chosen Koreans may be genetically as different as a Korean and an Italian. Any ethnic group contains 85% of the human genetic diversity of the world. Genetic data shows that no matter how population groups are defined, two people from the same population group are about as different from each other as two people from any two different population groups.

[127][160][161][162]

Most of the world's genetic diversity is represented in Africa.

Current genetic research have demonstrated that humans on the

African continent are the most genetically diverse.

[163] There is more human genetic diversity in Africa than anywhere else on Earth. The genetic structure of Africans was traced to 14 ancestral population clusters. Human genetic diversity decreases in native populations with migratory distance from Africa and this is thought to be the result of

bottlenecks during human migration.

[164][165] Humans have lived in Africa for the longest time, which has allowed accumulation of a higher diversity of genetic mutations in these populations. Only part of Africa's population migrated out of the continent, bringing just part of the original African genetic variety with them. African populations harbor genetic alleles that are not found in other places of the world. All the common alleles found in populations outside of Africa are found on the African continent.

[127]

Geographical distribution of human variation is complex and constantly shifts through time which reflects complicated human evolutionary history. Most human biological variation is

clinally distributed and blends gradually from an area to the next. Groups of people around the world have different frequencies of

polymorphic genes. Furthermore, different traits are non-concordant and each have different clinal distribution. Adaptability varies both from person to person and from population to population. The most efficient adaptive responses are found in geographical populations where the environmental stimuli are the strongest (e.g.

Tibetans are highly adapted to high altitudes). The clinal geographic genetic variation is further complicated by the migration and mixing between human populations which has been occurring since prehistoric times.

[127][166][167][168][169][170]

Human variation is highly non-concordant: most of the genes do not cluster together and are not inherited together. Skin and hair color are not correlated to height, weight, or athletic ability. Human species do not share the same patterns of variation through geography. Skin color varies with latitude and certain people are tall or have brown hair. There is a statistical correlation between particular features in a population, but different features are not expressed or inherited together. Thus, genes which code for superficial physical traits – such as skin color, hair color, or height – represent a minuscule and insignificant portion of the human genome and do not correlate with genetic affinity. Dark-skinned populations that are found in Africa, Australia, and South Asia are not closely related to each other.

[134][139][169][170][171][172] Even within the same region, physical phenotype is not related to genetic affinity: dark-skinned

Ethiopians are more closely related to light-skinned

Armenians than to dark-skinned

Bantu populations.

[173] Despite

pygmy populations of

South East Asia (

Andamanese) having similar physical features with African pygmy populations such as short stature, dark skin, and curly hair, they are not genetically closely related to these populations.

[174] Genetic variants affecting superficial anatomical features (such as skin color) – from a genetic perspective, are essentially meaningless – they involve a few hundred of the billions of nucleotides in a person's DNA.

[175] Individuals with the same morphology do not necessarily cluster with each other by lineage, and a given lineage does not include only individuals with the same trait complex.

[127][161][176]

Due to practices of group

endogamy, allele frequencies cluster locally around kin groups and lineages, or by national, ethnic, cultural and linguistic boundaries, giving a detailed degree of correlation between genetic clusters and population groups when considering many alleles simultaneously. Despite this, there are no genetic boundaries around local populations that biologically mark off any

discrete groups of humans. Human variation is continuous, with no clear points of demarcation. There are no large clusters of relatively homogeneous people and almost every individual has genetic alleles from several ancestral groups.

[127][168][169][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185]

Psychology

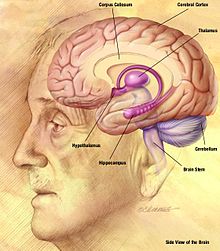

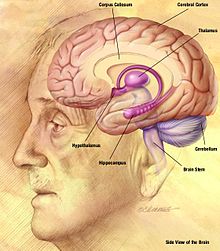

Drawing of the

human brain, showing several important structures

The human brain, the focal point of the

central nervous system in humans, controls the

peripheral nervous system. In addition to controlling "lower", involuntary, or primarily

autonomic activities such as

respiration and

digestion, it is also the locus of "higher" order functioning such as

thought,

reasoning, and

abstraction.

[186] These

cognitive processes constitute the

mind, and, along with their

behavioral consequences, are studied in the field of

psychology.

Generally regarded as more capable of these higher order activities, the human brain is believed to be more "intelligent" in general than that of any other known species. While some non-human species are capable of creating structures and

using simple tools—mostly through instinct and mimicry—human technology is vastly more complex, and is constantly evolving and improving through time.

Sleep and dreaming

Humans are generally

diurnal. The average sleep requirement is between seven and nine hours per day for an adult and nine to ten hours per day for a child; elderly people usually sleep for six to seven hours. Having less sleep than this is common among humans, even though

sleep deprivation can have negative health effects. A sustained restriction of adult sleep to four hours per day has been shown to correlate with changes in physiology and mental state, including reduced memory, fatigue, aggression, and bodily discomfort.

[187] During sleep humans dream. In dreaming humans experience sensory images and sounds, in a sequence which the dreamer usually perceives more as an apparent participant than as an observer. Dreaming is stimulated by the

pons and mostly occurs during the

REM phase of sleep.

Consciousness and thought

Humans are one of the relatively few species to have sufficient self-awareness

to recognize themselves in a mirror.

[188] Already at 18 months, most human children are aware that the mirror image is not another person.

[189]

Lecture at the Faculty of Biomedical Engineering,

CTU, in Prague.

The human brain

perceives the external world through the

senses, and each individual human is influenced greatly by his or her experiences, leading to

subjective views of

existence and the passage of time. Humans are variously said to possess consciousness,

self-awareness, and a mind, which correspond roughly to the mental processes of

thought. These are said to possess qualities such as self-awareness,

sentience,

sapience, and the ability to perceive the relationship between

oneself and one's

environment. The extent to which the mind constructs or experiences the outer world is a matter of debate, as are the definitions and validity of many of the terms used above.

The physical aspects of the mind and brain, and by extension of the nervous system, are studied in the field of

neurology, the more behavioral in the field of psychology, and a sometimes loosely defined area between in the field of psychiatry, which treats mental illness and behavioral disorders. Psychology does not necessarily refer to the brain or nervous system, and can be framed purely in terms of

phenomenological or

information processing theories of the mind. Increasingly, however, an understanding of brain functions is being included in psychological theory and practice, particularly in areas such as

artificial intelligence,

neuropsychology, and

cognitive neuroscience.

The nature of thought is central to psychology and related fields.

Cognitive psychology studies

cognition, the

mental processes' underlying behavior. It uses

information processing as a framework for understanding the mind. Perception, learning, problem solving, memory, attention, language and emotion are all well researched areas as well. Cognitive psychology is associated with a school of thought known as

cognitivism, whose adherents argue for an

information processing model of mental function, informed by

positivism and

experimental psychology. Techniques and models from cognitive psychology are widely applied and form the mainstay of psychological theories in many areas of both research and applied psychology. Largely focusing on the development of the human mind through the life span,

developmental psychology seeks to understand how people come to perceive, understand, and act within the world and how these processes change as they age. This may focus on intellectual, cognitive, neural, social, or

moral development.

Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is experience itself, and access consciousness, which is the processing of the things in experience.

[190] Phenomenal consciousness is the state of being conscious, such as when they say "I am conscious." Access consciousness is being conscious

of something in relation to abstract concepts, such as when one says "I am conscious of these words." Various forms of access consciousness include awareness, self-awareness, conscience,

stream of consciousness,

Husserl's phenomenology, and

intentionality. The concept of phenomenal consciousness, in modern history, according to some, is closely related to the concept of

qualia.

Social psychology links sociology with psychology in their shared study of the nature and causes of human social interaction, with an emphasis on how people think towards each other and how they relate to each other. The behavior and mental processes, both human and non-human, can be described through

animal cognition,

ethology,

evolutionary psychology, and

comparative psychology as well.

Human ecology is an

academic discipline that investigates how humans and human

societies interact with both their natural environment and the human

social environment.

Motivation and emotion

Motivation is the driving force of desire behind all deliberate

actions of humans. Motivation is based on emotion—specifically, on the search for

satisfaction (positive emotional experiences), and the avoidance of conflict. Positive and negative is defined by the individual brain state, which may be influenced by

social norms: a person may be driven to

self-injury or

violence because their

brain is conditioned to create a positive response to these actions. Motivation is important because it is involved in the performance of all learned responses. Within

psychology,

conflict avoidance and the

libido are seen to be primary motivators. Within

economics, motivation is often seen to be based on

incentives; these may be

financial,

moral, or

coercive.

Religions generally posit divine or

demonic influences.

Happiness, or the state of being happy, is a human emotional condition. The definition of happiness is a common

philosophical topic. Some people might define it as the best condition that a human can have—a condition of

mental and physical

health. Others define it as

freedom from want and

distress; consciousness of the

good order of things; assurance of one's place in the

universe or

society.

Emotion has a significant influence on, or can even be said to control, human behavior, though historically many

cultures and

philosophers have for various reasons discouraged allowing this influence to go unchecked. Emotional experiences perceived as

pleasant, such as

love, admiration, or joy, contrast with those perceived as

unpleasant, like

hate,

envy, or

sorrow. There is often a distinction made between refined emotions that are socially learned and

survival oriented emotions, which are thought to be innate. Human exploration of emotions as separate from other neurological phenomena is worthy of note, particularly in cultures where emotion is considered separate from physiological state. In some cultural medical theories emotion is considered so synonymous with certain forms of physical health that no difference is thought to exist. The

Stoics believed excessive emotion was harmful, while some

Sufi teachers felt certain extreme emotions could yield a conceptual perfection, what is often translated as

ecstasy.

In modern scientific thought, certain refined emotions are considered a complex neural trait innate in a variety of

domesticated and non-domesticated

mammals. These were commonly developed in reaction to superior survival mechanisms and intelligent interaction with each other and the environment; as such, refined emotion is not in all cases as discrete and separate from natural neural function as was once assumed. However, when humans function in civilized tandem, it has been noted that uninhibited acting on extreme emotion can lead to social disorder and

crime.

Sexuality and love

Human parents continue caring for their offspring long after they are born.

For humans, sexuality has important social functions: it creates physical intimacy, bonds and hierarchies among individuals, besides ensuring biological

reproduction. Sexual desire or

libido, is experienced as a bodily urge, often accompanied by strong emotions such as love,

ecstasy and

jealousy. The significance of sexuality in the human species is reflected in a number of physical features among them hidden

ovulation, the evolution of external

scrotum and

penis suggesting

sperm competition, the absence of an

os penis, permanent

secondary sexual characteristics and the forming of

pair bonds based on sexual attraction as a common social structure. Contrary to other primates that often advertise

estrus through visible signs, human females do not have a distinct or visible signs of ovulation plus they experience sexual desire outside of their fertile periods. These adaptations indicate that the meaning of sexuality in humans is similar to that found in the

bonobo, and that the complex human sexual behavior has a long

evolutionary history.

[191]

Human choices in acting on sexuality are commonly influenced by cultural norms which vary widely. Restrictions are often determined by religious beliefs or social customs. The pioneering researcher

Sigmund Freud believed that humans are born

polymorphously perverse, which means that any number of objects could be a source of pleasure. According to Freud humans then pass through five stages of

psychosexual development and can fixate on any stage because of various traumas during the process. For

Alfred Kinsey, another influential sex researcher, people can fall anywhere along a continuous scale of

sexual orientation, with only small minorities fully

heterosexual or

homosexual.

[192][193] Recent studies of

neurology and

genetics suggest people may be born predisposed to various sexual tendencies.

[194][195]

Culture

| Human society statistics |

| World population |

7.2 billion |

Population density

[citation needed] |

12.7 per km² (4.9 mi²) by total area

43.6 per km² (16.8 mi²) by land area |

Largest agglomerations

[citation needed] |

Beijing, Bogotá, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Delhi, Dhaka, Guangzhou, Istanbul, Jakarta, Karachi, Kinshasa, Kolkata, Lagos, Lima, London, Los Angeles, Manila, Mexico City, Moscow, Mumbai, New York City, Osaka, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Seoul, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tehran, Tianjin, Tokyo, Wuhan |

| Most widely spoken native languages[196] |

Chinese, Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Japanese, Javanese, German, Lahnda, Telugu, Marathi, Tamil, French, Vietnamese, Korean, Urdu, Italian, Malay, Persian, Turkish, Polish, Oriya |

| Most popular religions[197] |

Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism, Baha'i |

GDP (nominal)

[citation needed] |

$36,356,240 million USD

($5,797 USD per capita) |

GDP (PPP)

[citation needed] |

$51,656,251 million IND

($8,236 per capita) |

Humans often live in family-based social structures.

Humans are highly social beings and tend to live in large complex social groups. More than any other creature, humans are capable of utilizing systems of

communication for self-expression, the exchange of ideas, and

organization, and as such have created complex

social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups. Human groups range from the size of families to

nations. Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety

[clarification needed] of values, social norms, and rituals, which together form the basis of human

society.

Culture is defined here as patterns of complex symbolic behavior, i.e. all behavior that is not innate but which has to be learned through social interaction with others; such as the use of distinctive

material and

symbolic systems, including language, ritual, social organization, traditions, beliefs and technology.

Language

While many species

communicate,

language is unique to humans, a defining feature of humanity, and a

cultural universal. Unlike the limited systems of other animals, human language is open – an infinite number of meanings can be produced by combining a limited number of symbols. Human language also has the capacity of

displacement, using words to represent things and happenings that are not presently or locally occurring, but reside in the shared imagination of interlocutors.

[82] Language differs from other forms of communication in that it is

modality independent; the same meanings can be conveyed through different media, auditively in speech, visually by sign language or writing, and even through tactile media such as

braille. Language is central to the communication between humans, and to the sense of identity that unites nations, cultures and ethnic groups. The invention of writing systems at least five thousand years ago allowed the preservation of language on material objects, and was a major technological advancement. The science of

linguistics describes the structure and function of language and the relationship between languages. There are approximately six thousand different languages currently in use, including

sign languages, and many thousands more that are

extinct.

[198]

Gender roles

The sexual division of humans into male and female has been marked culturally by a corresponding division of roles, norms,

practices, dress, behavior,

rights,

duties,

privileges,

status, and

power.

Cultural differences by gender have often been believed to have arisen naturally out of a division of reproductive labor; the biological fact that women give birth led to their further cultural responsibility for nurturing and caring for children. Gender roles have varied historically, and challenges to predominant gender norms have recurred in many societies.

Kinship

All human societies organize, recognize and classify types of social relationships based on relations between parents and children (

consanguinity), and relations through marriage (

affinity). These kinds of relations are generally called kinship relations. In most societies kinship places mutual responsibilities and expectations of solidarity on the individuals that are so related, and those who recognize each other as kinsmen come to form networks through which other social institutions can be regulated. Among the many functions of kinship is the ability to form

descent groups, groups of people sharing a common line of descent, which can function as political units such as

clans.

Another function is the way in which kinship unites families through marriage, forming

kinship alliances between groups of wife-takers and wife-givers. Such alliances also often have important political and economical ramifications, and may result in the formation of political organization above the community level. Kinship relations often includes regulations for whom an individual should or shouldn't marry. All societies have rules of

incest taboo, according to which marriage between certain kinds of kin relations are prohibited – such rules vary widely between cultures. Some societies also have rules of preferential marriage with certain kin relations, frequently with either

cross or parallel cousins. Rules and norms for marriage and social behavior among kinsfolk is often reflected in the systems of

kinship terminology in the various languages of the world. In many societies kinship relations can also be formed through forms of co-habitation, adoption, fostering, or companionship, which also tends to create relations of enduring solidarity (

nurture kinship).

Ethnicity

Humans often form ethnic groups, such groups tend to be larger than kinship networks and be organized around a common identity defined variously in terms of shared ancestry and history, shared cultural norms and language, or shared biological phenotype. Such ideologies of shared characteristics are often perpetuated in the form of powerful, compelling narratives that give legitimacy and continuity to the set of shared values. Ethnic groupings often correspond to some level of political organization such as the

band,

tribe,

city state or

nation. Although ethnic groups appear and disappear through history, members of ethnic groups often conceptualize their groups as having histories going back into the deep past. Such ideologies give ethnicity a powerful role in defining

social identity and in constructing solidarity between members of an ethno-political unit. This unifying property of ethnicity has been closely tied to the rise of the

nation state as the predominant form of political organization in the 19th and 20th century.

[199][200][201][202][203][204]

Society, government, and politics

Russian honor guard at Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Alexander Garden welcomes Michael G. Mullen.

Society is the system of organizations and institutions arising from interaction between humans. A state is an organized political community occupying a definite territory, having an organized government, and possessing internal and external

sovereignty. Recognition of the state's claim to independence by other states, enabling it to enter into international agreements, is often important to the establishment of its statehood. The "state" can also be defined in terms of domestic conditions, specifically, as conceptualized by

Max Weber, "a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the 'legitimate' use of physical force within a given territory."

[205]

Government can be defined as the political means of creating and enforcing

laws; typically via a

bureaucratic hierarchy. Politics is the process by which decisions are made within groups; this process often involves conflict as well as compromise. Although the term is generally applied to behavior within governments, politics is also observed in all human group interactions, including corporate, academic, and religious institutions. Many different political systems exist, as do many different ways of understanding them, and many definitions overlap. Examples of governments include

monarchy,

Communist state,

military dictatorship,

theocracy, and

liberal democracy, the last of which is considered dominant today. All of these issues have a direct relationship with economics.

Trade and economics

Trade is the voluntary exchange of goods and services, and is a form of economics. A mechanism that allows trade is called a

market. Modern traders instead generally negotiate through a medium of exchange, such as money. As a result, buying can be separated from selling, or

earning. Because of specialization and

division of labor, most people concentrate on a small aspect of manufacturing or service, trading their labor for products. Trade exists between regions because different regions have an

absolute or

comparative advantage in the production of some tradable commodity, or because different regions' size allows for the benefits of

mass production.

Economics is a

social science which studies the production, distribution, trade, and consumption of goods and services. Economics focuses on measurable variables, and is broadly divided into two main branches:

microeconomics, which deals with individual agents, such as households and businesses, and macroeconomics, which considers the economy as a whole, in which case it considers

aggregate supply and

demand for money,

capital and

commodities. Aspects receiving particular attention in economics are

resource allocation, production, distribution, trade, and

competition. Economic logic is increasingly applied to any problem that involves choice under scarcity or determining economic

value.

War

Soldiers in front of the wood of Hougoumont during the reenactment of the battle of Waterloo (1815), June 2011, Waterloo, Belgium.

War is a state of organized armed conflict between

states or

non-state actors. War is characterized by the use of lethal

violence between

combatants and/or upon

non-combatants to achieve military goals through force. Lesser, often spontaneous conflicts, such as brawls,

riots,

revolts, and

melees, are not considered to be warfare.

Revolutions can be

nonviolent or an organized and armed revolution which denotes a state of war. During the 20th century, it is estimated that between 167 and 188 million people died as a result of war.

[206] A common definition defines war as a series of

military campaigns between at least two opposing sides involving a dispute over

sovereignty, territory,

resources,

religion, or other issues. A war between internal elements of a state is a

civil war. Among animals, all-out war against fellow members of the same species occurs only among large societies of humans and

ants.

There have been a wide variety of

rapidly advancing tactics throughout the history of war, ranging from

conventional war to

asymmetric warfare to

total war and

unconventional warfare. Techniques include

hand to hand combat, the use of

ranged weapons,

naval warfare, and, more recently,

air support. Military intelligence has often played a key role in determining victory and defeat. Propaganda, which often includes information, slanted opinion and disinformation, plays a key role in maintaining unity within a warring group, and/or sowing discord among opponents. In

modern warfare,

soldiers and

combat vehicles are used to control the land,

warships the sea, and

aircraft the sky. These fields have also overlapped in the forms of

marines,

paratroopers,

aircraft carriers, and

surface-to-air missiles, among others.

Satellites in

low Earth orbit have made outer space a factor in warfare as well as it is used for detailed intelligence gathering, however no known aggressive actions have been

taken from space.

Material culture and technology

An array of Neolithic artifacts, including bracelets, axe heads, chisels, and polishing tools.

Stone tools were used by proto-humans at least 2.5 million years ago.

[207] The

controlled use of fire began around 1.5 million years ago. Since then, humans have made major advances, developing complex technology to create tools to aid their lives and allowing for other advancements in culture. Major leaps in technology include the discovery of

agriculture – what is known as the

Neolithic Revolution, and the invention of automated machines in the

Industrial Revolution.

Archaeology attempts to tell the story of past or lost cultures in part by close examination of the

artifacts they produced. Early humans left

stone tools,

pottery, and

jewelry that are particular to various regions and times.

Body culture

Throughout history, humans have altered their appearance by wearing clothing

[208][209] and

adornments, by trimming or

shaving hair or by means of body modifications.

Body modification is the deliberate altering of the