Blue light is scattered more than other wavelengths by the gases in the atmosphere, surrounding Earth in a visibly blue layer when seen from space on board the ISS at an altitude of 335 km (208 mi).

Composition

of Earth's atmosphere by volume. Lower pie represents trace gases that

together compose about 0.038% of the atmosphere (0.043% with CO2 at 2014 concentration). Numbers are mainly from 1987, with CO2 and methane from 2009, and do not represent any single source.

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, commonly known as air, that surrounds the planet Earth and is retained by Earth's gravity. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for liquid water to exist on the Earth's surface, absorbing ultraviolet solar radiation, warming the surface through heat retention (greenhouse effect), and reducing temperature extremes between day and night (the diurnal temperature variation).

By volume, dry air contains 78.09% nitrogen, 20.95% oxygen, 0.93% argon, 0.04% carbon dioxide, and small amounts of other gases. Air also contains a variable amount of water vapor, on average around 1% at sea level, and 0.4% over the entire atmosphere. Air content and atmospheric pressure vary at different layers, and air suitable for use in photosynthesis by terrestrial plants and breathing of terrestrial animals is found only in Earth's troposphere and in artificial atmospheres.

The atmosphere has a mass of about 5.15×1018 kg,

three quarters of which is within about 11 km (6.8 mi; 36,000 ft) of

the surface. The atmosphere becomes thinner and thinner with increasing

altitude, with no definite boundary between the atmosphere and outer space. The Kármán line,

at 100 km (62 mi), or 1.57% of Earth's radius, is often used as the

border between the atmosphere and outer space. Atmospheric effects

become noticeable during atmospheric reentry of spacecraft at an altitude of around 120 km (75 mi). Several layers can be distinguished in the atmosphere, based on characteristics such as temperature and composition.

The study of Earth's atmosphere and its processes is called atmospheric science (aerology). Early pioneers in the field include Léon Teisserenc de Bort and Richard Assmann.

Composition

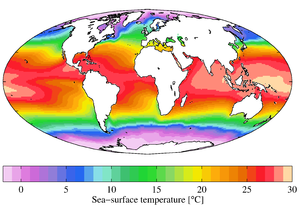

Mean atmospheric water vapor

The three major constituents of Earth's atmosphere are nitrogen, oxygen, and argon.

Water vapor accounts for roughly 0.25% of the atmosphere by mass. The

concentration of water vapor (a greenhouse gas) varies significantly

from around 10 ppm by volume in the coldest portions of the atmosphere

to as much as 5% by volume in hot, humid air masses, and concentrations

of other atmospheric gases are typically quoted in terms of dry air

(without water vapor). The remaining gases are often referred to as trace gases, among which are the greenhouse gases, principally carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Filtered air includes trace amounts of many other chemical compounds. Many substances of natural origin may be present in locally and seasonally variable small amounts as aerosols in an unfiltered air sample, including dust of mineral and organic composition, pollen and spores, sea spray, and volcanic ash. Various industrial pollutants also may be present as gases or aerosols, such as chlorine (elemental or in compounds), fluorine compounds and elemental mercury vapor. Sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide (SO2) may be derived from natural sources or from industrial air pollution.

| Gas | Volume(A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Formula | in ppmv(B) | in % |

| Nitrogen | N2 | 780,840 | 78.084 |

| Oxygen | O2 | 209,460 | 20.946 |

| Argon | Ar | 9,340 | 0.9340 |

| Carbon dioxide | CO2 | 400 | 0.04[8] |

| Neon | Ne | 18.18 | 0.001818 |

| Helium | He | 5.24 | 0.000524 |

| Methane | CH4 | 1.79 | 0.000179 |

| Not included in above dry atmosphere: | |||

| Water vapor(C) | H2O | 10–50,000(D) | 0.001%–5%(D) |

| notes: (A) volume fraction is equal to mole fraction for ideal gas only, also see volume (thermodynamics) (B) ppmv: parts per million by volume (C) Water vapor is about 0.25% by mass over full atmosphere (D) Water vapor strongly varies locally | |||

The relative concentration of gases remains constant until about 10,000 m (33,000 ft).

The

volume fraction of the main constituents of the Earth's atmosphere as a

function of height according to the MSIS-E-90 atmospheric model.

Stratification

Earth's atmosphere

Lower 4 layers of the atmosphere in 3 dimensions as seen diagonally

from above the exobase. Layers drawn to scale, objects within the

layers are not to scale. Aurorae shown here at the bottom of the

thermosphere can actually form at any altitude in this atmospheric

layer.

In general, air pressure and density decrease with altitude in the

atmosphere. However, temperature has a more complicated profile with

altitude, and may remain relatively constant or even increase with

altitude in some regions (see the temperature

section, below). Because the general pattern of the

temperature/altitude profile is constant and measurable by means of

instrumented balloon soundings,

the temperature behavior provides a useful metric to distinguish

atmospheric layers. In this way, Earth's atmosphere can be divided

(called atmospheric stratification) into five main layers. Excluding the

exosphere, the atmosphere has four primary layers, which are the

troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere. From highest to lowest, the five main layers are:

- Exosphere: 700 to 10,000 km (440 to 6,200 miles)

- Thermosphere: 80 to 700 km (50 to 440 miles)

- Mesosphere: 50 to 80 km (31 to 50 miles)

- Stratosphere: 12 to 50 km (7 to 31 miles)

- Troposphere: 0 to 12 km (0 to 7 miles)

Exosphere

The exosphere is the outermost layer of Earth's atmosphere (i.e. the upper limit of the atmosphere). It extends from the exobase,

which is located at the top of the thermosphere at an altitude of about

700 km above sea level, to about 10,000 km (6,200 mi; 33,000,000 ft)

where it merges into the solar wind.

This layer is mainly composed of extremely low densities of

hydrogen, helium and several heavier molecules including nitrogen,

oxygen and carbon dioxide closer to the exobase. The atoms and molecules

are so far apart that they can travel hundreds of kilometers without

colliding with one another. Thus, the exosphere no longer behaves like a

gas, and the particles constantly escape into space. These free-moving

particles follow ballistic trajectories and may migrate in and out of the magnetosphere or the solar wind.

The exosphere is located too far above Earth for any meteorological phenomena to be possible. However, the aurora borealis and aurora australis

sometimes occur in the lower part of the exosphere, where they overlap

into the thermosphere. The exosphere contains most of the satellites

orbiting Earth.

Thermosphere

The thermosphere is the second-highest layer of Earth's atmosphere.

It extends from the mesopause (which separates it from the mesosphere)

at an altitude of about 80 km (50 mi; 260,000 ft) up to the thermopause

at an altitude range of 500–1000 km (310–620 mi;

1,600,000–3,300,000 ft). The height of the thermopause varies

considerably due to changes in solar activity. Because the thermopause lies at the lower boundary of the exosphere, it is also referred to as the exobase. The lower part of the thermosphere, from 80 to 550 kilometres (50 to 342 mi) above Earth's surface, contains the ionosphere.

The temperature of the thermosphere gradually increases with height. Unlike the stratosphere beneath it, wherein a temperature inversion

is due to the absorption of radiation by ozone, the inversion in the

thermosphere occurs due to the extremely low density of its molecules.

The temperature of this layer can rise as high as 1500 °C (2700 °F),

though the gas molecules are so far apart that its temperature in the usual sense is not very meaningful. The air is so rarefied that an individual molecule (of oxygen, for example) travels an average of 1 kilometre (0.62 mi; 3300 ft) between collisions with other molecules.

Although the thermosphere has a high proportion of molecules with high

energy, it would not feel hot to a human in direct contact, because its

density is too low to conduct a significant amount of energy to or from

the skin.

This layer is completely cloudless and free of water vapor. However, non-hydrometeorological phenomena such as the aurora borealis and aurora australis are occasionally seen in the thermosphere. The International Space Station orbits in this layer, between 350 and 420 km (220 and 260 mi).

Mesosphere

The mesosphere is the third highest layer of Earth's atmosphere,

occupying the region above the stratosphere and below the thermosphere.

It extends from the stratopause at an altitude of about 50 km (31 mi;

160,000 ft) to the mesopause at 80–85 km (50–53 mi; 260,000–280,000 ft)

above sea level.

Temperatures drop with increasing altitude to the mesopause

that marks the top of this middle layer of the atmosphere. It is the

coldest place on Earth and has an average temperature around −85 °C (−120 °F; 190 K).

Just below the mesopause, the air is so cold that even the very

scarce water vapor at this altitude can be sublimated into

polar-mesospheric noctilucent clouds.

These are the highest clouds in the atmosphere and may be visible to

the naked eye if sunlight reflects off them about an hour or two after

sunset or a similar length of time before sunrise. They are most readily

visible when the Sun is around 4 to 16 degrees below the horizon.

Lightning-induced discharges known as transient luminous events (TLEs) occasionally form in the mesosphere above tropospheric thunderclouds. The mesosphere is also the layer where most meteors

burn up upon atmospheric entrance. It is too high above Earth to be

accessible to jet-powered aircraft and balloons, and too low to permit

orbital spacecraft. The mesosphere is mainly accessed by sounding rockets and rocket-powered aircraft.

Stratosphere

The stratosphere is the second-lowest layer of Earth's atmosphere. It

lies above the troposphere and is separated from it by the tropopause. This layer extends from the top of the troposphere at roughly 12 km (7.5 mi; 39,000 ft) above Earth's surface to the stratopause at an altitude of about 50 to 55 km (31 to 34 mi; 164,000 to 180,000 ft).

The atmospheric pressure at the top of the stratosphere is roughly 1/1000 the pressure at sea level.

It contains the ozone layer, which is the part of Earth's atmosphere

that contains relatively high concentrations of that gas. The

stratosphere defines a layer in which temperatures rise with increasing

altitude. This rise in temperature is caused by the absorption of ultraviolet radiation (UV) radiation from the Sun by the ozone layer,

which restricts turbulence and mixing. Although the temperature may be

−60 °C (−76 °F; 210 K) at the tropopause, the top of the stratosphere is

much warmer, and may be near 0 °C.

The stratospheric temperature profile creates very stable

atmospheric conditions, so the stratosphere lacks the weather-producing

air turbulence that is so prevalent in the troposphere. Consequently,

the stratosphere is almost completely free of clouds and other forms of

weather. However, polar stratospheric or nacreous clouds

are occasionally seen in the lower part of this layer of the atmosphere

where the air is coldest. The stratosphere is the highest layer that

can be accessed by jet-powered aircraft.

Troposphere

The troposphere is the lowest layer of Earth's atmosphere. It extends

from Earth's surface to an average height of about 12 km (7.5 mi;

39,000 ft), although this altitude varies from about 9 km (5.6 mi; 30,000 ft) at the geographic poles to 17 km (11 mi; 56,000 ft) at the Equator, with some variation due to weather. The troposphere is bounded above by the tropopause, a boundary marked in most places by a temperature inversion (i.e. a layer of relatively warm air above a colder one), and in others by a zone which is isothermal with height.

Although variations do occur, the temperature usually declines

with increasing altitude in the troposphere because the troposphere is

mostly heated through energy transfer from the surface. Thus, the lowest

part of the troposphere (i.e. Earth's surface) is typically the warmest

section of the troposphere. This promotes vertical mixing (hence, the

origin of its name in the Greek word τρόπος, tropos, meaning "turn"). The troposphere contains roughly 80% of the mass of Earth's atmosphere.

The troposphere is denser than all its overlying atmospheric layers

because a larger atmospheric weight sits on top of the troposphere and

causes it to be most severely compressed. Fifty percent of the total

mass of the atmosphere is located in the lower 5.6 km (3.5 mi;

18,000 ft) of the troposphere.

Nearly all atmospheric water vapor or moisture is found in the

troposphere, so it is the layer where most of Earth's weather takes

place. It has basically all the weather-associated cloud genus types

generated by active wind circulation, although very tall cumulonimbus

thunder clouds can penetrate the tropopause from below and rise into the

lower part of the stratosphere. Most conventional aviation activity takes place in the troposphere, and it is the only layer that can be accessed by propeller-driven aircraft.

Space Shuttle Endeavour

orbiting in the thermosphere. Because of the angle of the photo, it

appears to straddle the stratosphere and mesosphere that actually lie

more than 250 km below. The orange layer is the troposphere, which gives way to the whitish stratosphere and then the blue mesosphere.

Other layers

Within the five principal layers above, that are largely determined

by temperature, several secondary layers may be distinguished by other

properties:

- The ozone layer is contained within the stratosphere. In this layer ozone concentrations are about 2 to 8 parts per million, which is much higher than in the lower atmosphere but still very small compared to the main components of the atmosphere. It is mainly located in the lower portion of the stratosphere from about 15–35 km (9.3–21.7 mi; 49,000–115,000 ft), though the thickness varies seasonally and geographically. About 90% of the ozone in Earth's atmosphere is contained in the stratosphere.

- The ionosphere is a region of the atmosphere that is ionized by solar radiation. It is responsible for auroras. During daytime hours, it stretches from 50 to 1,000 km (31 to 621 mi; 160,000 to 3,280,000 ft) and includes the mesosphere, thermosphere, and parts of the exosphere. However, ionization in the mesosphere largely ceases during the night, so auroras are normally seen only in the thermosphere and lower exosphere. The ionosphere forms the inner edge of the magnetosphere. It has practical importance because it influences, for example, radio propagation on Earth.

- The homosphere and heterosphere are defined by whether the atmospheric gases are well mixed. The surface-based homosphere includes the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and the lowest part of the thermosphere, where the chemical composition of the atmosphere does not depend on molecular weight because the gases are mixed by turbulence. This relatively homogeneous layer ends at the turbopause found at about 100 km (62 mi; 330,000 ft), the very edge of space itself as accepted by the FAI, which places it about 20 km (12 mi; 66,000 ft) above the mesopause.

- Above this altitude lies the heterosphere, which includes the exosphere and most of the thermosphere. Here, the chemical composition varies with altitude. This is because the distance that particles can move without colliding with one another is large compared with the size of motions that cause mixing. This allows the gases to stratify by molecular weight, with the heavier ones, such as oxygen and nitrogen, present only near the bottom of the heterosphere. The upper part of the heterosphere is composed almost completely of hydrogen, the lightest element.

- The planetary boundary layer is the part of the troposphere that is closest to Earth's surface and is directly affected by it, mainly through turbulent diffusion. During the day the planetary boundary layer usually is well-mixed, whereas at night it becomes stably stratified with weak or intermittent mixing. The depth of the planetary boundary layer ranges from as little as about 100 metres (330 ft) on clear, calm nights to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) or more during the afternoon in dry regions.

The average temperature of the atmosphere at Earth's surface is 14 °C (57 °F; 287 K) or 15 °C (59 °F; 288 K), depending on the reference.

Physical properties

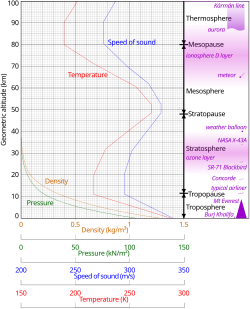

Comparison of the 1962 US Standard Atmosphere graph of geometric altitude against air density, pressure, the speed of sound and temperature with approximate altitudes of various objects.

Pressure and thickness

The average atmospheric pressure at sea level is defined by the International Standard Atmosphere as 101325 pascals (760.00 Torr; 14.6959 psi; 760.00 mmHg). This is sometimes referred to as a unit of standard atmospheres (atm). Total atmospheric mass is 5.1480×1018 kg (1.135×1019 lb),

about 2.5% less than would be inferred from the average sea level

pressure and Earth's area of 51007.2 megahectares, this portion being

displaced by Earth's mountainous terrain. Atmospheric pressure is the

total weight of the air above unit area at the point where the pressure

is measured. Thus air pressure varies with location and weather.

If the entire mass of the atmosphere had a uniform density equal to sea level density (about 1.2 kg per m3)

from sea level upwards, it would terminate abruptly at an altitude of

8.50 km (27,900 ft). It actually decreases exponentially with altitude,

dropping by half every 5.6 km (18,000 ft) or by a factor of 1/e every 7.64 km (25,100 ft), the average scale height

of the atmosphere below 70 km (43 mi; 230,000 ft). However, the

atmosphere is more accurately modeled with a customized equation for

each layer that takes gradients of temperature, molecular composition,

solar radiation and gravity into account.

In summary, the mass of Earth's atmosphere is distributed approximately as follows:

- 50% is below 5.6 km (18,000 ft).

- 90% is below 16 km (52,000 ft).

- 99.99997% is below 100 km (62 mi; 330,000 ft), the Kármán line. By international convention, this marks the beginning of space where human travelers are considered astronauts.

By comparison, the summit of Mt. Everest is at 8,848 m (29,029 ft);

commercial airliners typically cruise between 10 and 13 km (33,000 and 43,000 ft) where the thinner air improves fuel economy; weather balloons reach 30.4 km (100,000 ft) and above; and the highest X-15 flight in 1963 reached 108.0 km (354,300 ft).

Even above the Kármán line, significant atmospheric effects such as auroras still occur. Meteors

begin to glow in this region, though the larger ones may not burn up

until they penetrate more deeply. The various layers of Earth's ionosphere, important to HF radio propagation, begin below 100 km and extend beyond 500 km. By comparison, the International Space Station and Space Shuttle typically orbit at 350–400 km, within the F-layer of the ionosphere where they encounter enough atmospheric drag

to require reboosts every few months. Depending on solar activity,

satellites can experience noticeable atmospheric drag at altitudes as

high as 700–800 km.

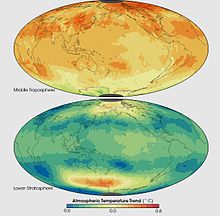

Temperature and speed of sound

Temperature trends in two thick layers of the atmosphere as measured between January 1979 and December 2005 by Microwave Sounding Units and Advanced Microwave Sounding Units on NOAA weather satellites. The instruments record microwaves emitted from oxygen molecules in the atmosphere.

The division of the atmosphere into layers mostly by reference to

temperature is discussed above. Temperature decreases with altitude

starting at sea level, but variations in this trend begin above 11 km,

where the temperature stabilizes through a large vertical distance

through the rest of the troposphere. In the stratosphere,

starting above about 20 km, the temperature increases with height, due

to heating within the ozone layer caused by capture of significant ultraviolet radiation from the Sun

by the dioxygen and ozone gas in this region. Still another region of

increasing temperature with altitude occurs at very high altitudes, in

the aptly-named thermosphere above 90 km.

Because in an ideal gas of constant composition the speed of sound

depends only on temperature and not on the gas pressure or density, the

speed of sound in the atmosphere with altitude takes on the form of the

complicated temperature profile (see illustration to the right), and

does not mirror altitudinal changes in density or pressure.

Density and mass

Temperature and mass density against altitude from the NRLMSISE-00 standard atmosphere model (the eight dotted lines in each "decade" are at the eight cubes 8, 27, 64, ..., 729)

The density of air at sea level is about 1.2 kg/m3 (1.2 g/L, 0.0012 g/cm3).

Density is not measured directly but is calculated from measurements of

temperature, pressure and humidity using the equation of state for air

(a form of the ideal gas law). Atmospheric density decreases as the altitude increases. This variation can be approximately modeled using the barometric formula. More sophisticated models are used to predict orbital decay of satellites.

The average mass of the atmosphere is about 5 quadrillion (5×1015) tonnes or 1/1,200,000 the mass of Earth. According to the American National Center for Atmospheric Research, "The total mean mass of the atmosphere is 5.1480×1018 kg with an annual range due to water vapor of 1.2 or 1.5×1015 kg,

depending on whether surface pressure or water vapor data are used;

somewhat smaller than the previous estimate. The mean mass of water

vapor is estimated as 1.27×1016 kg and the dry air mass as 5.1352 ±0.0003×1018 kg."

Optical properties

Solar radiation (or sunlight) is the energy Earth receives from the Sun.

Earth also emits radiation back into space, but at longer wavelengths

that we cannot see. Part of the incoming and emitted radiation is

absorbed or reflected by the atmosphere. In May 2017, glints of light,

seen as twinkling from an orbiting satellite a million miles away, were

found to be reflected light from ice crystals in the atmosphere.

Scattering

When light passes through Earth's atmosphere, photons interact with it through scattering. If the light does not interact with the atmosphere, it is called direct radiation and is what you see if you were to look directly at the Sun. Indirect radiation is light that has been scattered in the atmosphere. For example, on an overcast

day when you cannot see your shadow there is no direct radiation

reaching you, it has all been scattered. As another example, due to a

phenomenon called Rayleigh scattering,

shorter (blue) wavelengths scatter more easily than longer (red)

wavelengths. This is why the sky looks blue; you are seeing scattered

blue light. This is also why sunsets are red. Because the Sun is close

to the horizon, the Sun's rays pass through more atmosphere than normal

to reach your eye. Much of the blue light has been scattered out,

leaving the red light in a sunset.

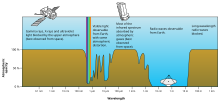

Absorption

Rough plot of Earth's atmospheric transmittance (or opacity) to various wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, including visible light.

Different molecules absorb different wavelengths of radiation. For example, O2 and O3 absorb almost all wavelengths shorter than 300 nanometers. Water (H2O)

absorbs many wavelengths above 700 nm. When a molecule absorbs a

photon, it increases the energy of the molecule. This heats the

atmosphere, but the atmosphere also cools by emitting radiation, as

discussed below.

The combined absorption spectra of the gases in the atmosphere leave "windows" of low opacity, allowing the transmission of only certain bands of light. The optical window runs from around 300 nm (ultraviolet-C) up into the range humans can see, the visible spectrum (commonly called light), at roughly 400–700 nm and continues to the infrared to around 1100 nm. There are also infrared and radio windows that transmit some infrared and radio waves at longer wavelengths. For example, the radio window runs from about one centimeter to about eleven-meter waves.

Emission

Emission is the opposite of absorption, it is when an object

emits radiation. Objects tend to emit amounts and wavelengths of

radiation depending on their "black body"

emission curves, therefore hotter objects tend to emit more radiation,

with shorter wavelengths. Colder objects emit less radiation, with

longer wavelengths. For example, the Sun is approximately 6,000 K (5,730 °C; 10,340 °F),

its radiation peaks near 500 nm, and is visible to the human eye. Earth

is approximately 290 K (17 °C; 62 °F), so its radiation peaks near

10,000 nm, and is much too long to be visible to humans.

Because of its temperature, the atmosphere emits infrared

radiation. For example, on clear nights Earth's surface cools down

faster than on cloudy nights. This is because clouds (H2O) are strong absorbers and emitters of infrared radiation. This is also why it becomes colder at night at higher elevations.

The greenhouse effect

is directly related to this absorption and emission effect. Some gases

in the atmosphere absorb and emit infrared radiation, but do not

interact with sunlight in the visible spectrum. Common examples of these

are CO2 and H2O.

Refractive index

The refractive index

of air is close to, but just greater than 1. Systematic variations in

refractive index can lead to the bending of light rays over long optical

paths. One example is that, under some circumstances, observers onboard

ships can see other vessels just over the horizon because light is refracted in the same direction as the curvature of Earth's surface.

The refractive index of air depends on temperature, giving rise to refraction effects when the temperature gradient is large. An example of such effects is the mirage.

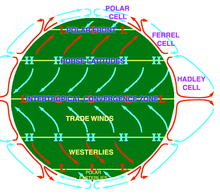

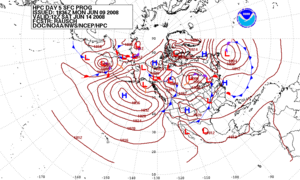

Circulation

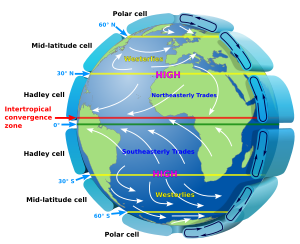

An idealised view of three large circulation cells.

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air through the troposphere, and the means (with ocean circulation)

by which heat is distributed around Earth. The large-scale structure of

the atmospheric circulation varies from year to year, but the basic

structure remains fairly constant because it is determined by Earth's

rotation rate and the difference in solar radiation between the equator

and poles.

Evolution of Earth's atmosphere

Earliest atmosphere

The first atmosphere consisted of gases in the solar nebula, primarily hydrogen. There were probably simple hydrides such as those now found in the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), notably water vapor, methane and ammonia.

Second atmosphere

Outgassing from volcanism, supplemented by gases produced during the late heavy bombardment of Earth by huge asteroids, produced the next atmosphere, consisting largely of nitrogen plus carbon dioxide and inert gases.

A major part of carbon-dioxide emissions dissolved in water and reacted

with metals such as calcium and magnesium during weathering of crustal

rocks to form carbonates that were deposited as sediments. Water-related

sediments have been found that date from as early as 3.8 billion years

ago.

About 3.4 billion years ago, nitrogen formed the major part of

the then stable "second atmosphere". The influence of life has to be

taken into account rather soon in the history of the atmosphere, because

hints of early life-forms appear as early as 3.5 billion years ago.

How Earth at that time maintained a climate warm enough for liquid

water and life, if the early Sun put out 30% lower solar radiance than

today, is a puzzle known as the "faint young Sun paradox".

The geological record however shows a continuous relatively warm surface during the complete early temperature record of Earth – with the exception of one cold glacial phase about 2.4 billion years ago. In the late Archean Eon an oxygen-containing atmosphere began to develop, apparently produced by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria (see Great Oxygenation Event), which have been found as stromatolite fossils from 2.7 billion years ago. The early basic carbon isotopy (isotope ratio proportions) strongly suggests conditions similar to the current, and that the fundamental features of the carbon cycle became established as early as 4 billion years ago.

Ancient sediments in the Gabon

dating from between about 2,150 and 2,080 million years ago provide a

record of Earth's dynamic oxygenation evolution. These fluctuations in

oxygenation were likely driven by the Lomagundi carbon isotope excursion.

Third atmosphere

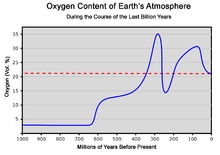

Oxygen content of the atmosphere over the last billion years

The constant re-arrangement of continents by plate tectonics

influences the long-term evolution of the atmosphere by transferring

carbon dioxide to and from large continental carbonate stores. Free

oxygen did not exist in the atmosphere until about 2.4 billion years ago

during the Great Oxygenation Event and its appearance is indicated by the end of the banded iron formations.

Before this time, any oxygen produced by photosynthesis was

consumed by oxidation of reduced materials, notably iron. Molecules of

free oxygen did not start to accumulate in the atmosphere until the rate

of production of oxygen began to exceed the availability of reducing

materials that removed oxygen. This point signifies a shift from a reducing atmosphere to an oxidizing atmosphere. O2 showed major variations until reaching a steady state of more than 15% by the end of the Precambrian. The following time span from 541 million years ago to the present day is the Phanerozoic Eon, during the earliest period of which, the Cambrian, oxygen-requiring metazoan life forms began to appear.

The amount of oxygen in the atmosphere has fluctuated over the

last 600 million years, reaching a peak of about 30% around 280 million

years ago, significantly higher than today's 21%. Two main processes

govern changes in the atmosphere: Plants use carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, releasing oxygen. Breakdown of pyrite and volcanic eruptions release sulfur

into the atmosphere, which oxidizes and hence reduces the amount of

oxygen in the atmosphere. However, volcanic eruptions also release

carbon dioxide, which plants can convert to oxygen. The exact cause of

the variation of the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere is not known.

Periods with much oxygen in the atmosphere are associated with rapid

development of animals. Today's atmosphere contains 21% oxygen, which is

great enough for this rapid development of animals.