Historically, liberal feminism largely grew out of and was often associated with social liberalism; the modern liberal feminist tradition notably includes both social liberal and social democratic streams, as well as many often diverging schools of thought such as equality feminism, social feminism, care-ethical liberal feminism, equity feminism, difference feminism, conservative liberal feminism, and liberal socialist feminism. Some forms of modern liberal feminism have been described as neoliberal feminism or "boardroom feminism". Liberal feminism is often closely associated with liberal internationalism. In many countries, particularly in the West but also in a number of secular states in the developing world, liberal feminism is associated with the concept of state feminism, and liberal feminism emphasizes constructive cooperation with the government and involvement in parliamentary and legislative processes to pursue reforms. Liberal feminism is also called "mainstream feminism", "reformist feminism", "egalitarian feminism", or historically "bourgeois feminism" (or bourgeois-liberal feminism), among other names. As one of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought, liberal feminism is often contrasted with socialist/Marxist feminism and radical feminism: unlike them, liberal feminism seeks gradual social progress and equality on the basis of liberal democracy rather than a revolution or radical reordering of society. Liberal feminism and mainstream feminism are very broad terms, frequently taken to encompass all feminism that is not radical or revolutionary socialist/Marxist and that instead pursues equality through political, legal, and social reform within a liberal democratic framework. As such, liberal feminists may subscribe to a range of different feminist beliefs and political ideologies within the democratic spectrum from the centre-left to the centre-right.

Inherently pragmatic in orientation, liberal feminists have emphasized building far-reaching support for feminist causes among both women and men, and among the political centre, the government and legislatures. In the 21st century, liberal feminism has taken a turn toward an intersectional understanding of gender equality, and modern liberal feminists support LGBT rights as a core feminist issue. Liberal feminists typically support laws and regulations that promote gender equality and ban practices that are discriminatory towards women; mainstream liberal feminists, particularly those of a social democratic bent, often support social measures to reduce material inequality within a liberal democratic framework. While rooted in first-wave feminism and traditionally focused on political and legal reform, the broader liberal feminist tradition may include parts of subsequent waves of feminism, especially third-wave feminism and fourth-wave feminism. The sunflower and the color gold, taken to represent enlightenment, became widely used symbols of mainstream liberal feminism and women's suffrage from the 1860s, originally in the United States and later also in parts of Europe.

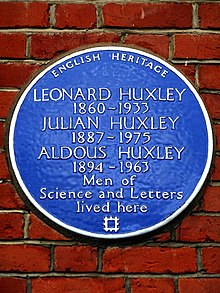

Origins

Terminology

The specific term "liberal feminism" is fairly modern, but its political tradition is much older. "Feminism" became the dominant term in English for the struggle for women's rights in the late 20th century, around a century after the organized liberal women's rights movement came into existence, but most western feminist historians contend that all movements working to obtain women's rights should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not (or do not) apply the term to themselves.

Historically, the bourgeois women's rights movement—the predecessor of modern liberal feminism—was mainly contrasted with the working-class or "proletarian" women's movements, which eventually developed into called socialist and Marxist feminism. Since the 1960s both liberal feminism and the "proletarian" or socialist/Marxist women's movements are also contrasted with radical feminism. Liberal feminism is usually included as one of the two, three, or four main traditions in the history of feminism.

Many liberal feminists embraced the term "feminism" in the 1970s or 1980s, although some initially expressed scepticism towards the term; for example the liberal feminist Norwegian Association for Women's Rights expressed scepticism towards the term "feminism" as late as 1980 because it could foster "unnecessary antagonism towards men", but accepted the term some years later as it increasingly became the mainstream general term for the women's rights struggle in the western world.

Movement

Liberal feminism ultimately has historical roots in classical liberalism and was often associated with social liberalism from the late 19th century. The goal for liberal feminists beginning in the late 18th century was to gain suffrage for women with the idea that this would allow them to gain individual liberty. They were concerned with gaining freedom through equality, diminishing men's cruelty to women, and gaining opportunities to become full persons. They believed that no government or custom should prohibit the due exercise of personal freedom. Early liberal feminists had to counter the assumption that only white men deserved to be full citizens. Pioneers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Judith Sargent Murray, and Frances Wright advocated for women's full political inclusion. In 1920, after nearly 50 years of intense activism, women were finally granted the right to vote and the right to hold public office in the United States, and in much of the Western world within a few decades before or a few decades after this time.

Liberal feminism was largely quiet in the United States for four decades after winning the vote. In the 1960s during the civil rights movement, liberal feminists drew parallels between systemic race discrimination and sex discrimination. Groups such as the National Organization for Women, the National Women's Political Caucus, and the Women's Equity Action League were all created at that time to further women's rights. In the U.S., these groups have worked, thus far unsuccessfully, for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment or "Constitutional Equity Amendment", in the hopes it will ensure that men and women are treated as equals under the law. Specific issues important to liberal feminists include but are not limited to reproductive rights and abortion access, sexual harassment, voting, education, fair compensation for work, affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.

Equal Rights Amendment

A fair number of American liberal feminists believe that equality in pay, job opportunities, political structure, social security, and education for women especially needs to be guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

Three years after women won the right to vote, the Equal Right Amendment (ERA) was introduced in Congress by Senator Charles Curtis Curtis and Representative Daniel Read Anthony Jr., both Republicans. This amendment stated that civil rights cannot be denied on the basis of one's sex. It was authored by Alice Paul, head of the National Women's Party, who led the suffrage campaign. Through the efforts of Alice Paul, the Amendment was introduced into each session of the United States Congress, but it was buried in committee in both Houses of Congress. In 1946, it was narrowly defeated by the full Senate, 38–35. In February 1970, twenty NOW leaders disrupted the hearings of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, demanding the ERA be heard by the full Congress. In May of that year, the Senate Subcommittee began hearings on the ERA under Senator Birch Bayh. In June, the ERA finally left the House Judiciary Committee due to a discharge petition filed by Representative Martha Griffiths. In March 1972, the ERA was approved by the full Senate without changes, 84–8. Senator Sam Ervin and Representative Emanuel Celler succeeded in setting a time limit of seven years for ratification. The ERA then went to the individual states for approval but failed to win in enough of them (38) to become law. In 1978, Congress passed a disputed (less than supermajority) three-year extension on the original seven-year ratification limit, but the ERA could not gain approval by the needed number of states.

The state legislatures that were most hostile to the ERA were Utah, Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, and Oklahoma. The NOW holds that the single most obvious problem in passing the ERA was the gender and racial imbalance in the legislatures. More than 2/3 of the women and all of the African Americans in state legislatures voted for the ERA, but less than 50% of the white men in the targeted legislatures cast pro-ERA votes in 1982.

Philosophy

Equal rights

According to Anthony Giddens, liberal feminist theory "believes gender inequality is produced by reduced access for women and girls to civil rights and allocation of social resources such as education and employment." Catherine Rottenberg notes that the raison d'être of classic liberal feminism was "to pose an immanent critique of liberalism, revealing the gendered exclusions within liberal democracy’s proclamation of universal equality, particularly with respect to the law, institutional access, and the full incorporation of women into the public sphere." Rottenberg contrasts classic liberal feminism with modern neoliberal feminism which "seems perfectly in sync with the evolving neoliberal order."

At its core, liberal feminism believes in pragmatic "reforms against gender discrimination through the promotion of equal rights by engaging and formulating laws and policies that will ensure equality." Liberal feminists argue that society holds the false belief that women are, by nature, less intellectually and physically capable than men; thus it tends to discriminate against women in the academy, the forum, and the marketplace. Liberal feminists believe that "female subordination is rooted in a set of customary and legal constraints that blocks women's entrance to and success in the so-called public world", and strive for gender equality via political and legal reform. Cathrine Holst notes that "the bourgeois women's rights movement was liberal or liberal feminist. The bourgeois women's rights advocates fought for women’s civil liberties and rights: freedom of speech, freedom of movement, the right to vote, freedom of association, inheritance rights, property rights, and freedom of trade – and for women's access to education and working life. In short, women should have the same freedoms and rights as men."

Political liberalism gave feminism a familiar platform for convincing others that their reforms "could and should be incorporated into existing law". Liberal feminists argued that women, like men, be regarded as autonomous individuals, and likewise be accorded the rights of such. Inherently pragmatic, liberal feminists tend to focus on practical reforms of laws and policies in order to achieve equality; liberal feminism has a more individualistic approach to justice than left-wing branches of feminism such as socialist or radical feminism. Susan Wendell argues that "liberal feminism is an historical tradition that grew out of liberalism, as can be seen very clearly in the work of such feminists as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, but feminists who took principles from that tradition have developed analyses and goals that go far beyond those of 18th and 19th century liberal feminists, and many feminists who have goals and strategies identified as liberal feminist ... reject major components of liberalism" in a modern or party-political sense; she highlights "equality of opportunity" as a defining feature of liberal feminism. Helga Hernes notes that liberal feminism has often been critical of liberalist political positions and that liberal feminism and liberalism in general are not necessarily the same.

Lucy E. Bailey notes that liberal feminism is characterized by "its focus on individual rights and reform through the state" and that it has "been instrumental in fueling women's rights movements in diverse contexts and remains a familiar and widespread form of feminist thought. Liberal feminism emerged as a distinct political tradition during the Enlightenment (...) Liberal feminist theory emphasizes women's individual rights to autonomy and proposes remedies for gender inequities through, variously, removing legal and social constraints or advancing conditions that support women's equality."

LGBT rights

Liberal feminist organizations are broadly inclusive and thus tend to support LGBT rights in the modern era. For example, the two largest American feminist organizations, the liberal feminist National Organization for Women (NOW) and the League of Women Voters (LWV) both regard LGBT rights as a core feminist issue and vehemently support trans rights and oppose transphobia. NOW president Terry O'Neill said the struggle against transphobia is a feminist issue. NOW has affirmed that "trans women are women, trans girls are girls." In a further statement NOW said that "trans women are women. They deserve equal opportunity, health care, a safe community & workplace, and they deserve to play sports. They have a right to have their identity respected without conforming to perceived sex and gender identity standards. We stand with you."

Similarly, the traditionally dominant liberal feminist international non-governmental organization, the International Alliance of Women (IAW) and its affiliates are trans-inclusive; IAW's Icelandic affiliate, the Icelandic Women's Rights Association, has stated that "IWRA works for the rights of all women. Feminism without trans women is no feminism at all." On Women's Rights Day in Iceland in 2020, the Icelandic Women's Rights Association organised an event together with Trans Ísland that saw several different feminist organisations in the country discuss strategies to stop anti-trans sentiment from increasing its influence in Iceland. Later that year, Trans Ísland was unanimously granted status as a member association of the Icelandic Women's Rights Association. In 2021 the International Alliance of Women and the Icelandic Women's Rights Association organized an event on how the women's movement could counter "anti-trans voices [that] are becoming ever louder and [that] are threatening feminist solidarity across borders." The Danish Women's Society supports LGBTQA rights, and has stated that it takes homophobia and transphobia very seriously, and that "we support all initiatives that promote the rights of gay and transgender people." The Norwegian Association for Women's Rights is trans-inclusive and supports legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. The Deutscher Frauenring is intersectional and opposes transphobia. In November 2020, on Trans Day of Remembrance, the National Women's Council of Ireland and Amnesty International Ireland co-signed a statement along with a number of LGBT+ and human rights groups condemning trans-exclusionary feminism. The letter called upon the media and politicians "to no longer provide legitimate representation for those that share bigoted beliefs, that are aligned with far-right ideologies and seek nothing but harm and division" and stated that "these fringe internet accounts stand against affirmative medical care of transgender people, and they stand against the right to self-identification of transgender people in this country. In summation, they stand against trans, women’s, and gay rights by aligning themselves with far-right tropes and stances."

UN Women works to promote gender equality and the rights of women and LGBTIQ+ people, and "urgently calls on communities and governments around the world to stand up for LGBTIQ+ rights." The Association for Women's Rights in Development (AWID) supports LGBTIQ rights and opposes the anti-gender movement, and has described trans-exclusionary feminists as "trojan horses in human rights spaces" that seek to undermine human rights; AWID said that anti-trans activity is "alarming," that "the 'sex-based' rhetoric misuses concepts of sex and gender to push a deeply discriminatory agenda" and that "trans-exclusionary feminists (...) undermine progressions on gender and sexuality and protection of rights of marginalized groups." To be clear, while there are debates, UN Women is said to be a liberal feminist organization. As evidence, although they seem to acknowledge intersectionality, UN Women still evaluate gender equality in each country by looking at how integrated women are into hegemonic society, for example they measure how many women are in a position of CEO and politician.

Schools of thought

Liberal feminism as a broad school of thought and main tradition in feminism includes many different varieties, such as equality feminism, social feminism, equity feminism, and difference feminism. State feminism is often linked to liberal feminism, particularly in Western countries. Some forms of modern liberal feminism have been described as neoliberal feminism.

Neoliberal feminism

Neoliberal feminism emerged in the 2010s. In The Rise of Neoliberal Feminism, Rottenberg defines neoliberalism as a “new form of selfhood, which encourages people as individual subjects responsible for their own well-being” as well as it ensures the individual right to their own autonomous decision making (p. 421). The author argues that neoliberal feminism emerged from neoliberalism being espoused by “increasingly high-powered women”, for example Anne-Marie Slaughters and Sheryl Sandberg (p. 418). Even though Sandberg states in Lean In that she “supports who want to eliminate external barriers” so that every woman can lean in, she argues that as the first step, women should lean in so as to reform society (p. 3). Therefore, women who are worried about the possibility of having a child at the cost of her career should not “lean back” but keep leaning in (p. 51). Sandberg does not seek reformation of social system, which she even calls “the rat race” (p. 51). Neoliberal feminists apparently realize the gender inequality. However, they value women who accept the responsibility for taking balance between work and family following the theory of neoliberalism, in which they do not accuse the state but take care of their own well-being. As a political reason for emergence of neoliberal feminism, Rottenberg asserts that by “responsiblizing” women, neoliberalism feminism is useful for diffusing social issues (i.e., sexism, racism, capitalism).

Libertarian feminism

Individualist or libertarian feminism is sometimes grouped as one of many branches of feminism with historical roots in liberal feminism but tends to diverge significantly from mainstream liberal feminism on many issues. For example, "libertarian feminism does not require social measures to reduce material inequality; in fact, it opposes such measures ... in contrast, liberal feminism may support such requirements and egalitarian versions of feminism insist on them." Libertarian feminists tend to focus more on sexual politics, a topic traditionally of less concern to liberal feminists. Mainstream liberal feminists, such as the National Organization for Women, tend to oppose prostitution, but are somewhat divided on prostitution politics, unlike both libertarian and radical feminists.

Western feminism

Liberal feminist organizations such as the International Alliance of Women tend to be supportive of liberal democratic states' foreign and security policy, and maintained a clear pro-Western stance throughout the Cold War. From the second half of the 20th century women in development has increasingly become an important topic for liberal feminist organizations.

Hillary Clinton is often considered a liberal feminist, and has defined "feminist" in accordance with the liberal feminist definition as "someone who believes in equal rights." Some articles do not clearly describe her as a liberal feminist, yet argue that Clinton's policy and her white privilege ignore many women, for instance women of color, low-income women, and immigrants while NOW (2015) admire her as “a trailblazer for women with an impressive record of public service where she put women’s rights at the forefront”.

Equity feminism

Equity feminism is a form of liberal feminism discussed since the 1980s, specifically a kind of classically liberal or libertarian feminism, emphasizing equality under law, equal freedoms, and rights, rather than profound social transformations.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy refers to Wendy McElroy, Joan Kennedy Taylor, Cathy Young, Rita Simon, Katie Roiphe, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, Christine Stolba, and Christina Hoff Sommers as equity feminists. Steven Pinker, an evolutionary psychologist, identifies himself as an equity feminist, which he defines as "a moral doctrine about equal treatment that makes no commitments regarding open empirical issues in psychology or biology". Barry Kuhle asserts that equity feminism is compatible with evolutionary psychology, in contrast to gender feminism.

Writers

Feminist writers associated with this theory include Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mill, Helen Taylor, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Gina Krog; Second Wave feminists Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Simone de Beauvoir; and Third Wave feminist Rebecca Walker.

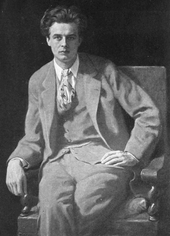

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) has been very influential in her writings as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman commented on society's view of women and encouraged women to use their voices in making decisions separate from decisions previously made for them. Wollstonecraft "denied that women are, by nature, more pleasure seeking and pleasure giving than men. She reasoned that if they were confined to the same cages that trap women, men would develop the same flawed characters. What Wollstonecraft most wanted for women was personhood." She argued that patriarchal oppression is a form of slavery that could no longer be ignored. Wollstonecraft argued that the inequality between men and women existed due to the disparity between their educations. Along with Judith Sargent Murray and Frances Wright, Wollstonecraft was one of the first major advocates for women's full inclusion in politics.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) was one of the most influential women in first wave feminism. An American social activist, she was instrumental in orchestrating the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, which was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Not only was the suffragist movement important to Stanton, she also was involved in women's parental and custody rights, divorce laws, birth control, employment and financial rights, among other issues. Her partner in this movement was the equally influential Susan B. Anthony. Together, they fought for a linguistic shift in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to include "female". Additionally, in 1890 she founded the National American Woman Suffrage Association and presided as president until 1892. She produced many speeches, resolutions, letters, calls, and petitions that fed the first wave and kept the spirit alive. Furthermore, by gathering a large number of signatures, she aided the passage of the Married Women's Property Act of 1848 which considered women legally independent of their husbands and granted the property of their own. Together these women formed what was known as the NWSA (National Women Suffrage Association), which focused on working with legislatures and the courts to gain suffrage.

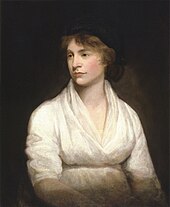

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) believed that both sexes should have equal rights under the law and that "until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely." Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same "genuine unselfishness" that men did in providing for their families. This unselfishness Mill advocated is the one "that motivates people to take into account the good of society as well as the good of the individual person or small family unit". Similar to Mary Wollstonecraft, Mill compared sexual inequality to slavery, arguing that their husbands are often just as abusive as masters and that a human being controls nearly every aspect of life for another human being. In his book The Subjection of Women, Mill argues that three major parts of women's lives are hindering them: society and gender construction, education, and marriage. He also argues that sex inequality is greatly inhibiting the progress of humanity.

Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan (1921–2006) was a liberal feminist prominent in the 1960s. She was a co-founder and the first president of NOW, and contributed to the second wave feminism. Her book The Feminine Mystique, written in 1963, became a landmark bestseller and significantly influential by rebuking the fulfillment of middle-class women for domestic lives. In her book, Friedan reversed the discourse of American housewife as ideal and happy and pointed out dissatisfaction and loneliness which were faced by many American women in the 1950s and 1960s. She described these women's experience as a problem without name and called for financial independence of women for liberation. Many articles argue that Friedan was unaware of her white privilege and failed to realize intersectionality of women. For example, by stating that "only economic independence can free a woman to marry for love", Friedan attempted to encourage every woman not to "be afraid of flying" and seek their own lives outside of household. She also argued the necessity of a social and political women's movement by raising the black civil rights movement as a model. However, she did not try to combine those movements together, nor was black women's experience considered in feminist context. Instead, she presumed the separation of issues of race and sex.

Notable liberal feminists

- 18th century

- 19th century

- 20th century

- 21st century

Organizations

National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is the largest liberal feminist organization in the United States. It supports the Equal Rights Amendment, reproductive rights including freer access to abortion, as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights (LGBT rights), and economic justice. It opposes violence against women and racism.

Various other issues the National Organization for Women also deals with are:

- Affirmative action

- Disability rights

- EcoFeminism

- Family

- Opposing right-wing causes contrary to NOW's interests

- Global feminism

- Women's health

- Immigration

- Promotion of nominating judges with feminist viewpoints

- Legislation

- Legal recognition of same-sex marriages

- Media activism

- Mothers' economic rights

- Working for peace; opposition to conflicts such as the Iraq War

- Social Security

- Supreme Court

- Title IX/Education

- Welfare

- Workplace discrimination

- Women in the military

- Young feminist programs

National Women's Political Caucus

The National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC), founded in 1971, is the only national organization in the U.S. dedicated exclusively to increasing women's participation in all areas of political and public life as elected and appointed officials, as delegates to national party conventions, as judges in the state and federal courts, and as lobbyists, voters and campaign organizers.

Founders of NWPC include such prominent women as Gloria Steinem, author, lecturer and founding editor of Ms. Magazine; former Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm; former Congresswoman Bella Abzug; Dorothy Height, former president of the National Council of Negro Women; Jill Ruckelshaus, former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner; Ann Lewis, former Political Director of the Democratic National Committee; Elly Peterson, former vice-chair of the Republican National Committee; LaDonna Harris, Indian rights leader; Liz Carpenter, author, lecturer and former press secretary to Lady Bird Johnson; and Eleanor Holmes Norton, Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and former chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

These women were spurred by Congress' failure to pass the Equal Rights Amendment in 1970. They believed legal, economic and social equity would come about only when women were equally represented among the nation's political decision-makers. Their faith that women's interests would best be served by women lawmakers has been confirmed time and time again, as women in Congress, state legislatures and city halls across the country have introduced, fought for and won legislation to eliminate sex discrimination and meet women's changing needs.

Women's Equity Action League

The Women's Equity Action League (WEAL) was a national membership organization, with state chapters and divisions, founded in 1968 and dedicated to improving the status and lives of women primarily through education, litigation, and legislation. It was a more conservative organization than NOW and was formed largely by former members of that organization who did not share NOW's the assertive stance on socio-sexual issues, particularly on abortion rights. WEAL spawned a sister organization, the Women's Equity Action League Fund, which was incorporated in 1972 "to help secure legal rights for women and to carry on educational and research projects on sex discrimination". The two organizations merged in 1981 following changes in the tax code. WEAL dissolved in 1989.

The stated purposes of WEAL were:

- to promote greater economic progress on the part of American women;

- to press for full enforcement of existing anti-discriminatory laws on behalf of women;

- to seek correction of de facto discrimination against women;

- to gather and disseminate information and educational material;

- to investigate instances of, and seek solutions to, economic, educational, tax, and employment problems affecting women;

- to urge that girls be prepared to enter more advanced career fields;

- to seek reappraisal of federal, state, and local laws and practices limiting women's employment opportunities;

- to combat by all lawful means, job discrimination against women in the pay, promotional or advancement policies of governmental or private employers;

- to seek the cooperation and coordination of all American women, individually or as organizations *to attain these objectives, whether through legislation, litigation, or other means and by doing any and all things necessary or incident thereto.

Norwegian Association for Women's Rights

Norway has had a tradition of government-supported liberal feminism since 1884, when the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights (NKF) was founded with the support of the progressive establishment within the then-dominant governing Liberal Party (which received 63.4% of the votes in the election the following year). The association's founders included five Norwegian prime ministers, and several of its early leaders were married to prime ministers. Rooted in first-wave liberal feminism, it works "to promote gender equality and women's and girls' human rights within the framework of liberal democracy and through political and legal reform". NKF members had key roles in developing the government apparatus and legislation related to gender equality in Norway since 1884; with the professionalization of gender equality advocacy from 1970s, the "Norwegian government adopted NKF's [equality] ideology as its own" and adopted laws and established government institutions such as the Gender Equality Ombud based on NKF's proposals; the new government institutions to promote gender equality were also largely built and led by prominent NKF members such as Eva Kolstad, NKF's former president and the first Gender Equality Ombud. NKF's feminist tradition has often been described as Norway's state feminism. The term state feminism itself was coined by NKF member Helga Hernes. Although it grew out of 19th-century progressive liberalism, Norwegian liberal feminism is not limited to liberalism in a modern party-political sense, and NKF is broadly representative of the democratic political spectrum from the center-left to the center-right, including the social democratic Labour Party. Norwegian supreme court justice and former NKF President Karin Maria Bruzelius has described NKF's liberal feminism as "a realistic, sober, practical feminism".

Other organizations

Symbolism

The sunflower (and sometimes by analogy the Sun) and the color yellow/gold (Or in heraldry), taken to represent enlightenment, became widely used symbols of the mainstream liberal women's rights movement and women's suffrage from the 1860s, originally in the United States and later also in parts of Europe. The suffragists and liberal feminists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony encouraged the use of the sunflower by wearing sunflower pins when campaigning for the right to vote in 1867 in Kansas. Hence the colors yellow and white became the main colors of the international liberal (also called mainstream or bourgeois) suffrage movement around the turn of the century, notably used by the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. Historians Cheris Kramarae and Paula A. Treichler noted that

Colors were important in the iconography of the suffrage movement. The use of the color gold began with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony’s campaign in Kansas in 1867 and derived from the color of the sunflower, the Kansas state symbol. Suffragists used gold pins, ribbons, sashes, and yellow roses to symbolize their cause. In 1876, during the U.S. Centennial, women wore yellow ribbons and sang the song “The Yellow Ribbon.” In 1916, suffragists staged “The Golden Lane” at the national Democratic convention; to reach the convention hall, all delegates had to walk through a line of women stretching several blocks long, dressed in white with gold sashes, carrying yellow umbrellas, and accompanied by hundreds of yards of draped gold bunting. Gold also signified enlightenment, the professed goal of the mainstream U.S. suffrage movement.

— Cheris Kramarae & Paula A. Treichler

The sunflower and/or the color yellow/gold remain in use among the older liberal (bourgeois) feminist organizations such as the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights and the International Alliance of Women that were founded during the struggle for women's suffrage.

The color yellow is also widely used as a symbol of liberalism in general.

Criticism

Gender roles

Critics of liberal feminism argue that its individualist assumptions make it difficult to see the ways in which underlying social structures and values disadvantage women. They argue that even if women are not dependent upon individual men, they are still dependent upon a patriarchal state. These critics believe that institutional changes, like the introduction of women's suffrage, are insufficient to emancipate women.

According to Zhang and Rios, "liberal feminism tends to be adopted by 'mainstream' (i.e., middle-class) women who do not disagree with the current social structure." They found that liberal feminist beliefs were viewed as the dominant and "default" form of feminism.

One of the more prevalent critiques of liberal feminism is that it, as a study, allows too much of its focus to fall on a "metamorphosis" of women into men, and in doing so, it disregards the significance of the traditional role of women. One of the leading scholars who have critiqued liberal feminism is radical feminist Catherine A. MacKinnon, an American lawyer, writer, and social activist. Specializing in issues regarding sex equality, she has been intimately involved in cases regarding the definition of sexual harassment and sex discrimination. She, among other radical feminist scholars, views liberalism and feminism as incompatible, because liberalism offers women a "piece of the pie as currently and poisonously baked".

Racial attitudes

bell hooks' main criticism of the philosophies of liberal feminism is that they focus too much on an equality with men in their own class. She maintains that the "cultural basis of group oppression" is the biggest challenge, in that liberal feminists tend to ignore it.

Another important critique of liberal feminism posits the existence of a "white woman's burden" or white savior complex. The phrase "white woman's burden" derives from "The White Man's Burden". Critics such as Black feminists and postcolonial feminists assert that mainstream liberal feminism reflects only the values of middle-class, heterosexual, white women and fails to appreciate the position of women of different races, cultures, or classes. With this, white liberal feminists reflect the issues that underlie the white savior complex. They do not understand women that are outside the dominant society but try to "save" or "help" them by pushing them to assimilate into their ideals of feminism. According to such critics, liberal feminism fails to recognize the power dynamics that are in play with women of color and transnational women which involve multiple sources of oppression.