One of the five paintings of Extermination of Evil portrays Sendan Kendatsuba, one of the eight guardians of Buddhist law, banishing evil.

Evil, in a general sense, is the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage is often used more narrowly to talk about profound wickedness. It is generally seen as taking multiple possible forms, such as the form of personal moral evil commonly associated with the word, or impersonal natural evil (as in the case of natural disasters or illnesses), and in religious thought, the form of the demonic or supernatural/eternal.

Evil can denote profound immorality, but typically not without some basis in the understanding of the human condition, where strife and suffering (cf. Hinduism) are the true roots of evil. In certain religious contexts, evil has been described as a supernatural force. Definitions of evil vary, as does the analysis of its motives. Elements that are commonly associated with personal forms of evil involve unbalanced behavior including anger, revenge, hatred, psychological trauma, expediency, selfishness, ignorance, destruction and neglect.

Evil is also sometimes perceived as the dualistic antagonistic binary opposite to good, in which good should prevail and evil should be defeated. In cultures with Buddhist spiritual influence, both good and evil are perceived as part of an antagonistic duality that itself must be overcome through achieving Nirvana. The philosophical questions regarding good and evil are subsumed into three major areas of study: meta-ethics concerning the nature of good and evil, normative ethics concerning how we ought to behave, and applied ethics

concerning particular moral issues. While the term is applied to events

and conditions without agency, the forms of evil addressed in this

article presume an evildoer or doers.

While some religions focus on good vs. evil, other religions and

philosophies deny evil's existence and usefulness in describing people.

Etymology

The modern English word evil (Old English yfel) and its cognates such as the German Übel and Dutch euvel are widely considered to come from a Proto-Germanic reconstructed form of *ubilaz, comparable to the Hittite huwapp- ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European form *wap- and suffixed zero-grade form *up-elo-. Other later Germanic forms include Middle English evel, ifel, ufel, Old Frisian evel (adjective and noun), Old Saxon ubil, Old High German ubil, and Gothic ubils.

The root meaning of the word is of obscure origin though shown to be akin to modern German Das Übel (although evil is normally translated as Das Böse) with the basic idea of transgressing.

Chinese moral philosophy

As with Buddhism, in Confucianism or Taoism there is no direct analogue to the way good and evil are opposed although reference to demonic influence is common in Chinese folk religion.

Confucianism's primary concern is with correct social relationships and

the behavior appropriate to the learned or superior man. Thus evil would correspond to wrong behavior. Still less does it map into Taoism, in spite of the centrality of dualism in that system,

but the opposite of the cardinal virtues of Taoism, compassion,

moderation, and humility can be inferred to be the analogue of evil in

it.

European philosophy

Spinoza

Benedict de Spinoza states

1. By good, I understand that which we certainly know is useful to us.

2. By evil, on the contrary, I understand that which we certainly know hinders us from possessing anything that is good.

Spinoza assumes a quasi-mathematical

style and states these further propositions which he purports to prove

or demonstrate from the above definitions in part IV of his Ethics :

- Proposition 8 "Knowledge of good or evil is nothing but affect of joy or sorrow in so far as we are conscious of it."

- Proposition 30 "Nothing can be evil through that which it possesses in common with our nature, but in so far as a thing is evil to us it is contrary to us."

- Proposition 64 "The knowledge of evil is inadequate knowledge."

- Corollary "Hence it follows that if the human mind had none but adequate ideas, it would form no notion of evil."

- Proposition 65 "According to the guidance of reason, of two things which are good, we shall follow the greater good, and of two evils, follow the less."

- Proposition 68 "If men were born free, they would form no conception of good and evil so long as they were free."

Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche, in a rejection of Judeo-Christian morality, addresses this in two works Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals

where he essentially says that the natural, functional non-good has

been socially transformed into the religious concept of evil by the

slave mentality of the weak and oppressed masses who resent their

masters (the strong).

Psychology

Carl Jung

Carl Jung, in his book Answer to Job and elsewhere, depicted evil as the dark side of God. People tend to believe evil is something external to them, because they project their shadow onto others. Jung interpreted the story of Jesus as an account of God facing his own shadow.

Even though the book may have had a sudden birth, its gestation

period in Jung's unconscious was long. The subject of God, and what Jung

saw as the dark side of God, was a lifelong preoccupation. An emotional

and theoretical struggle with the core nature of deity is evident in

Jung's earliest fantasies and dreams, as well as in his complex

relationships with his father (a traditional minister), his mother (who

had a strong spiritual-mystical dimension), and the Christian church

itself. Jung's account of his childhood in his quasi-autobiography,

Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage, 1963), provides deep,

personal background about his early religious roots– and conflicts.

Philip Zimbardo

In 2007, Philip Zimbardo suggested that people may act in evil ways as a result of a collective identity. This hypothesis, based on his previous experience from the Stanford prison experiment, was published in the book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.

Religion

Problem of evil and source

Most monotheistic religions posit that the singular God is all-powerful, all-knowing, and completely good. The problem of evil

asks how the apparent contradiction of these properties and the

observed existence of evil in the world might be resolved. Scholars

have examined the question of suffering caused by and in both humans and

animals, suffering caused by nature (like storms and disease). These

religions tend to attribute the source of evil to something other than God, such as demonic beings or human disobedience.

Polytheistic and non-theistic religions do not have such an

apparent contradiction, but many seek to explain or identify the source

of evil or suffering. These include concepts of evil as a necessary

balancing or enabling force, a consequence of past deeds (karma in Indian religions), or as an illusion, possibly produced by ignorance or failure to achieve enlightenment.

Non-religious atheism generally accepts evil acts as a feature of human actions arising from intelligent brains shaped by evolution, and suffering from nature as a result of complex natural systems simply following physical laws.

Abrahamic religions

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith

asserts that evil is non-existent and that it is a concept reflecting

lack of good, just as cold is the state of no heat, darkness is the

state of no light, forgetfulness the lacking of memory, ignorance the

lacking of knowledge. All of these are states of lacking and have no

real existence.

Thus, evil does not exist and is relative to man. `Abdu'l-Bahá, son of the founder of the religion, in Some Answered Questions states:

"Nevertheless a doubt occurs to the mind—that is, scorpions and

serpents are poisonous. Are they good or evil, for they are existing

beings? Yes, a scorpion is evil in relation to man; a serpent is evil in

relation to man; but in relation to themselves they are not evil, for

their poison is their weapon, and by their sting they defend

themselves."

Thus, evil is more of an intellectual concept than a true

reality. Since God is good, and upon creating creation he confirmed it

by saying it is Good (Genesis 1:31) evil cannot have a true reality.

Christianity

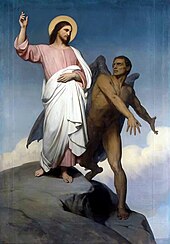

The devil, in opposition to the will of God, represents evil and tempts Christ, the personification of the character and will of God. Ary Scheffer, 1854.

Christian theology draws its concept of evil from the Old and New Testaments. The Christian Bible exercises "the dominant influence upon ideas about God and evil in the Western world."

In the Old Testament, evil is understood to be an opposition to God as

well as something unsuitable or inferior such as the leader of the fallen angels Satan In the New Testament the Greek word poneros is used to indicate unsuitability, while kakos is used to refer to opposition to God in the human realm. Officially, the Catholic Church extracts its understanding of evil from its canonical antiquity and the Dominican theologian, Thomas Aquinas, who in Summa Theologica defines evil as the absence or privation of good. French-American theologian Henri Blocher

describes evil, when viewed as a theological concept, as an

"unjustifiable reality. In common parlance, evil is 'something' that

occurs in the experience that ought not to be."

In Mormonism, mortal life is viewed as a test of faith, where one's choices are central to the Plan of Salvation. See Agency (LDS Church).

Evil is that which keeps one from discovering the nature of God. It is

believed that one must choose not to be evil to return to God.

Christian Science

believes that evil arises from a misunderstanding of the goodness of

nature, which is understood as being inherently perfect if viewed from

the correct (spiritual) perspective. Misunderstanding God's reality

leads to incorrect choices, which are termed evil. This has led to the

rejection of any separate power being the source of evil, or of God as

being the source of evil; instead, the appearance of evil is the result

of a mistaken concept of good. Christian Scientists argue that even the

most evil person does not pursue evil for its own sake, but from

the mistaken viewpoint that he or she will achieve some kind of good

thereby.

Islam

There is no concept of absolute evil in Islam, as a fundamental universal principle that is independent from and equal with good in a dualistic sense. Although the Quran mentions the biblical forbidden tree, it never refers to it as the 'tree of knowledge of good and evil'. Within Islam, it is considered essential to believe that all comes from God, whether it is perceived as good or bad by individuals; and things that are perceived as evil or bad

are either natural events (natural disasters or illnesses) or caused by

humanity's free will. Much more the behavior of beings with free will,

then they disobey God's orders, harming others or putting themselves

over God or others, is considered to be evil.

Evil doesn't necessarily refer to evil as an ontological or moral

category, but often to harm or as the intention and consequence of an

action, but also to unlawfull actions.

Unproductive actions or those who do not produce benefits are also thought of as evil.

A typical understanding of evil is reflected by Al-Ash`ari founder of Asharism.

Accordingly, qualifying something as evil depends on the circumstances

of the observer. An event or an action itself is neutral, but it

receives its qualification by God. Since God is omnipotent and nothing

can exist outside of God's power, God's will determine, whether or not

something is evil.

Judaism

In Judaism, evil is not real, it is per se

not part of God's creation, but comes into existence through man's bad

actions. Human beings are responsible for their choices, and so have the

free will to choose good (life in olam haba) or bad (death in heaven). (Deuteronomy 28:20) Judaism stresses obedience to God's 613 commandments of the Written Torah (see also Tanakh) and the collective body of Jewish religious laws expounded in the Oral Torah and Shulchan Aruch (see also Mishnah and the Talmud). In Judaism, there is no prejudice in one's becoming good or evil at the time of birth, since full responsibility comes with Bar and Bat Mitzvah, when Jewish boys become 13, and girls become 12 years old.

Ancient Egyptian Religion

Evil in the religion of ancient Egypt is known as Isfet, "disorder/violence". It is the opposite of Maat, "order", and embodied by the serpent god Apep, who routinely attempts to kill the sun god Ra

and is stopped by nearly every other deity. Isfet is not a primordial

force, but the consequence of free will and an individual's struggle

against the non-existence embodied by Apep, as evidenced by the fact

that it was born from Ra's umbilical cord instead of being recorded in

the religion's creation myths.

Indian religions

Buddhism

Extermination of Evil, The God of Heavenly Punishment, from the Chinese tradition of yin and yang. Late Heian period (12th-century Japan)

The primal duality in Buddhism is between suffering and enlightenment, so the good vs. evil splitting has no direct analogue in it. One may infer from the general teachings of the Buddha that the catalogued causes of suffering are what correspond in this belief system to 'evil'.

Practically this can refer to 1) the three selfish

emotions—desire, hate and delusion; and 2) to their expression in

physical and verbal actions. See ten unvirtuous actions in Buddhism. Specifically, evil

means whatever harms or obstructs the causes for happiness in this

life, a better rebirth, liberation from samsara, and the true and

complete enlightenment of a buddha (samyaksambodhi).

"What is evil? Killing is evil, lying is evil, slandering is

evil, abuse is evil, gossip is evil: envy is evil, hatred is evil, to

cling to false doctrine is evil; all these things are evil. And what is

the root of evil? Desire is the root of evil, illusion is the root of

evil." Gautama Siddhartha, the founder of Buddhism, 563–483 BC.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the concept of Dharma or righteousness clearly divides the world into good and evil, and clearly explains that wars have to be waged sometimes to establish and protect Dharma, this war is called Dharmayuddha. This division of good and evil is of major importance in both the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The main emphasis in Hinduism is on bad action, rather than bad people. The Hindu holy text, the Bhagavad Gita, speaks of the balance of good and evil. When this balance goes off, divine incarnations come to help to restore this balance.

Sikhism

In

adherence to the core principle of spiritual evolution, the Sikh idea of

evil changes depending on one's position on the path to liberation. At

the beginning stages of spiritual growth, good and evil may seem neatly

separated. Once one's spirit evolves to the point where it sees most

clearly, the idea of evil vanishes and the truth is revealed. In his

writings Guru Arjan

explains that, because God is the source of all things, what we believe

to be evil must too come from God. And because God is ultimately a

source of absolute good, nothing truly evil can originate from God.

Nevertheless, Sikhism, like many other religions, does

incorporate a list of "vices" from which suffering, corruption, and

abject negativity arise. These are known as the Five Thieves, called such due to their propensity to cloud the mind and lead one astray from the prosecution of righteous action. These are:

One who gives in to the temptations of the Five Thieves is known as "Manmukh", or someone who lives selfishly and without virtue. Inversely, the "Gurmukh,

who thrive in their reverence toward divine knowledge, rise above vice

via the practice of the high virtues of Sikhism. These are:

- Sewa, or selfless service to others.

- Nam Simran, or meditation upon the divine name.

Zoroastrianism

In the originally Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, the world is a battleground between the god Ahura Mazda (also called Ormazd) and the malignant spirit Angra Mainyu (also called Ahriman). The final resolution of the struggle between good and evil was supposed to occur on a day of Judgement,

in which all beings that have lived will be led across a bridge of

fire, and those who are evil will be cast down forever. In Afghan

belief, angels and saints are beings sent to help us achieve the path towards goodness.

Question of a universal definition

A

fundamental question is whether there is a universal, transcendent

definition of evil, or whether evil is determined by one's social or

cultural background. C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, maintained that there are certain acts that are universally considered evil, such as rape and murder.

The numerous instances in which rape or murder is morally affected by

social context call this into question. Up until the mid-19th century,

the United States—along with many other countries—practiced forms of slavery.

As is often the case, those transgressing moral boundaries stood to

profit from that exercise. Arguably, slavery has always been the same

and objectively evil, but men with a motivation to transgress will

justify that action.

Adolf Hitler is sometimes used as a modern symbol of evil. Hitler's policies and orders resulted in the deaths of about 40 million people.

The Nazis, during World War II, considered genocide to be acceptable, as did the Hutu Interahamwe in the Rwandan genocide.

One might point out, though, that the actual perpetrators of those

atrocities probably avoided calling their actions genocide, since the

objective meaning of any act accurately described by that word is to

wrongfully kill a selected group of people, which is an action that at

least their victims will understand to be evil. Universalists consider

evil independent of culture, and wholly related to acts or intents.

Thus, while the ideological leaders of Nazism and the Hutu Interhamwe

accepted (and considered it moral) to commit genocide, the belief in

genocide as fundamentally or universally evil holds that

those who instigated this genocide are actually evil. Hitler considered

it a moral duty to destroy Jews because he saw them as the root of all

of Germany's ills and the violence associated with communism. Osama bin Laden

saw Islam as under attack by Western and US influence, accusing the US

and Israel of forming a Crusader-Zionist alliance to destroy Islam, and

considering US troops in Saudi Arabia infidels in the land of Islam's

two holiest sites. He therefore considered non-Muslims and Shiite

Muslims evil people intent on destroying Islamic purity and therefore

heretic.

Given his mixed record of efforts to give the Cuban people

free-of-charge healthcare and education as well as opposing US hegemony

in Latin America, while crushing all opposition and wrecking the Cuban

economy, Fidel Castro saw himself as a Caribbean Robin Hood who considered the US and capitalism evil, while anti-Castro Cuban Americans,

Cuban dissidents, and other anti-communists saw Castro as the

personification of evil in late 20th-century Cuban and Latin American

history, viewing his Castroist ideology as just as evil as any other

form of communism and bashing him for locking up dissidents and killing

innocents by firing squads, while creating mayhem in the developing

world by working to foment violent communist revolutions in the Americas

and many African countries.

Philosophical questions

Approaches

Views on the nature of evil belong to the branch of philosophy known as ethics—which in modern philosophy is subsumed into three major areas of study:

- Meta-ethics, that seeks to understand the nature of ethical properties, statements, attitudes, and judgments.

- Normative ethics, investigates the set of questions that arise when considering how one ought to act, morally speaking.

- Applied ethics, concerned with the analysis of particular moral issues in private and public life.

Usefulness as a term

One school of thought that holds that no person is evil and that only acts may be properly considered evil. Psychologist and mediator Marshall Rosenberg claims that the root of violence is the very concept of evil or badness.

When we label someone as bad or evil, Rosenberg claims, it invokes the

desire to punish or inflict pain. It also makes it easy for us to turn

off our feelings towards the person we are harming. He cites the use of

language in Nazi Germany as being a key to how the German people were

able to do things to other human beings that they normally would not do.

He links the concept of evil to our judicial system, which seeks to

create justice via punishment—punitive justice—punishing acts that are seen as bad or wrong. He contrasts this approach with what he found in cultures where the idea of evil was non-existent. In such cultures

when someone harms another person, they are believed to be out of

harmony with themselves and their community, are seen as sick or ill and

measures are taken to restore them to a sense of harmonious relations

with themselves and others.

Psychologist Albert Ellis agrees, in his school of psychology called Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy,

or REBT. He says the root of anger, and the desire to harm someone, is

almost always related to variations of implicit or explicit

philosophical beliefs about other human beings. He further claims that

without holding variants of those covert or overt belief and

assumptions, the tendency to resort to violence in most cases is less

likely.

American psychiatrist M. Scott Peck on the other hand, describes evil as militant ignorance. The original Judeo-Christian concept of sin is as a process that leads one to miss the mark

and not achieve perfection. Peck argues that while most people are

conscious of this at least on some level, those that are evil actively

and militantly refuse this consciousness. Peck describes evil as a

malignant type of self-righteousness which results in a projection of

evil onto selected specific innocent victims (often children or other

people in relatively powerless positions). Peck considers those he calls

evil to be attempting to escape and hide from their own conscience

(through self-deception) and views this as being quite distinct from the

apparent absence of conscience evident in sociopaths.

According to Peck, an evil person:

- Is consistently self-deceiving, with the intent of avoiding guilt and maintaining a self-image of perfection

- Deceives others as a consequence of their own self-deception

- Psychologically projects his or her evils and sins onto very specific targets, scapegoating those targets while treating everyone else normally ("their insensitivity toward him was selective")

- Commonly hates with the pretense of love, for the purposes of self-deception as much as the deception of others

- Abuses political or emotional power ("the imposition of one's will upon others by overt or covert coercion")

- Maintains a high level of respectability and lies incessantly in order to do so

- Is consistent with his or her sins. Evil people are defined not so much by the magnitude of their sins, but by their consistency (of destructiveness)

- Is unable to think from the viewpoint of their victim

- Has a covert intolerance to criticism and other forms of narcissistic injury

He also considers certain institutions may be evil, as his discussion of the My Lai Massacre and its attempted coverup illustrate. By this definition, acts of criminal and state terrorism would also be considered evil.

Necessity

Martin Luther believed that occasional minor evil could have a positive effect

Martin Luther

argued that there are cases where a little evil is a positive good. He

wrote, "Seek out the society of your boon companions, drink, play, talk

bawdy, and amuse yourself. One must sometimes commit a sin out of hate

and contempt for the Devil, so as not to give him the chance to make one scrupulous over mere nothings ... "

According to the "realist" schools of political philosophy,

leaders should be indifferent to good or evil, taking actions based only

upon advantage; this approach to politics was put forth most famously

by Niccolò Machiavelli, a 16th-century Florentine writer who advised tyrants that "it is far safer to be feared than loved."

The international relations theories of realism and neorealism, sometimes called realpolitik advise politicians to explicitly ban absolute moral and ethical

considerations from international politics, and to focus on

self-interest, political survival, and power politics, which they hold

to be more accurate in explaining a world they view as explicitly amoral

and dangerous. Political realists usually justify their perspectives by

stating that morals and politics should be separated as two unrelated

things, as exerting authority often involves doing something not moral.

Machiavelli wrote: "there will be traits considered good that, if

followed, will lead to ruin, while other traits, considered vices which

if practiced achieve security and well being for the prince."

Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan,

was a materialist and claimed that evil is actually good. He was

responding to the common practice of describing sexuality or disbelief

as evil, and his claim was that when the word evil is used to

describe the natural pleasures and instincts of men and women or the

skepticism of an inquiring mind, the things called and feared as evil

are really non-evil and in fact good.