Misogyny (/mɪˈsɒdʒɪni/) is the hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women or girls. Misogyny is manifest in numerous ways, including social exclusion, sex discrimination, hostility, androcentrism, patriarchy, male privilege, belittling of women, violence against women, and sexual objectification. Misogyny can be found within sacred texts of religions, mythologies, and Western philosophies.

Definitions

According to sociologist Allan G. Johnson, "misogyny is a cultural attitude of hatred for females because they are female". Johnson argues that:Misogyny .... is a central part of sexist prejudice and ideology and, as such, is an important basis for the oppression of females in male-dominated societies. Misogyny is manifested in many different ways, from jokes to pornography to violence to the self-contempt women may be taught to feel toward their own bodies.Sociologist Michael Flood at the University of Wollongong defines misogyny as the hatred of women, and notes:

Though most common in men, misogyny also exists in and is practiced by women against other women or even themselves. Misogyny functions as an ideology or belief system that has accompanied patriarchal, or male-dominated societies for thousands of years and continues to place women in subordinate positions with limited access to power and decision making. […] Aristotle contended that women exist as natural deformities or imperfect males […] Ever since, women in Western cultures have internalised their role as societal scapegoats, influenced in the twenty-first century by multimedia objectification of women with its culturally sanctioned self-loathing and fixations on plastic surgery, anorexia and bulimia.Dictionaries define misogyny as "hatred of women" and as "hatred, dislike, or mistrust of women". In 2012, primarily in response to events occurring in the Australian Parliament, the Macquarie Dictionary (which documents Australian English and New Zealand English) expanded the definition to include not only hatred of women but also "entrenched prejudices against women". The counterpart of misogyny is misandry, the hatred or dislike of men; the antonym of misogyny is philogyny, the love or fondness of women.

Historical usage

Classical Greece

In his book City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens, J.W. Roberts argues that older than tragedy and comedy was a misogynistic tradition in Greek literature, reaching back at least as far as Hesiod. The term misogyny itself comes directly into English from the Ancient Greek word misogunia (μισογυνία), which survives in several passages.

The earlier, longer, and more complete passage comes from a moral tract known as On Marriage (c. 150 BC) by the stoic philosopher Antipater of Tarsus. Antipater argues that marriage is the foundation of the state, and considers it to be based on divine (polytheistic) decree. He uses misogunia to describe the sort of writing the tragedian Euripides eschews, stating that he "reject[s] the hatred of women in his writing" (ἀποθέμενος τὴν ἐν τῷ γράφειν μισογυνίαν). He then offers an example of this, quoting from a lost play of Euripides in which the merits of a dutiful wife are praised.

The other surviving use of the original Greek word is by Chrysippus, in a fragment from On affections, quoted by Galen in Hippocrates on Affections. Here, misogyny is the first in a short list of three "disaffections"—women (misogunia), wine (misoinia, μισοινία) and humanity (misanthrōpia, μισανθρωπία). Chrysippus' point is more abstract than Antipater's, and Galen quotes the passage as an example of an opinion contrary to his own. What is clear, however, is that he groups hatred of women with hatred of humanity generally, and even hatred of wine. "It was the prevailing medical opinion of his day that wine strengthens body and soul alike." So Chrysippus, like his fellow stoic Antipater, views misogyny negatively, as a disease; a dislike of something that is good. It is this issue of conflicted or alternating emotions that was philosophically contentious to the ancient writers. Ricardo Salles suggests that the general stoic view was that "[a] man may not only alternate between philogyny and misogyny, philanthropy and misanthropy, but be prompted to each by the other."

Aristotle has also been accused of being a misogynist; he has written that women were inferior to men. According to Cynthia Freeland (1994):

Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity': which contributes only matter and not form to the generation of offspring; that in general 'a woman is perhaps an inferior being'; that female characters in a tragedy will be inappropriate if they are too brave or too clever[.]In the Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic, Nickolas Pappas describes the "problem of misogyny" and states:

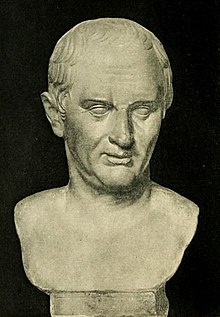

In the Apology, Socrates calls those who plead for their lives in court "no better than women" (35b)... The Timaeus warns men that if they live immorally they will be reincarnated as women (42b-c; cf. 75d-e). The Republic contains a number of comments in the same spirit (387e, 395d-e, 398e, 431b-c, 469d), evidence of nothing so much as of contempt toward women. Even Socrates' words for his bold new proposal about marriage... suggest that the women are to be "held in common" by men. He never says that the men might be held in common by the women... We also have to acknowledge Socrates' insistence that men surpass women at any task that both sexes attempt (455c, 456a), and his remark in Book 8 that one sign of democracy's moral failure is the sexual equality it promotes (563b).Misogynist is also found in the Greek—misogunēs (μισογύνης)—in Deipnosophistae (above) and in Plutarch's Parallel Lives, where it is used as the title of Heracles in the history of Phocion. It was the title of a play by Menander, which we know of from book seven (concerning Alexandria) of Strabo's 17 volume Geography, and quotations of Menander by Clement of Alexandria and Stobaeus that relate to marriage. A Greek play with a similar name, Misogunos (Μισόγυνος) or Woman-hater, is reported by Marcus Tullius Cicero (in Latin) and attributed to the poet Marcus Atilius.

Cicero reports that Greek philosophers considered misogyny to be caused by gynophobia, a fear of women.

It is the same with other diseases; as the desire of glory, a passion for women, to which the Greeks give the name of philogyneia: and thus all other diseases and sicknesses are generated. But those feelings which are the contrary of these are supposed to have fear for their foundation, as a hatred of women, such as is displayed in the Woman-hater of Atilius; or the hatred of the whole human species, as Timon is reported to have done, whom they call the Misanthrope. Of the same kind is inhospitality. And all these diseases proceed from a certain dread of such things as they hate and avoid.In summary, Greek literature considered misogyny to be a disease—an anti-social condition—in that it ran contrary to their perceptions of the value of women as wives and of the family as the foundation of society. These points are widely noted in the secondary literature.

— Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1st century BC.

Religion

Ancient Greek

In Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, Jack Holland argues that there is evidence of misogyny in the mythology of the ancient world. In Greek mythology according to Hesiod, the human race had already experienced a peaceful, autonomous existence as a companion to the gods before the creation of women. When Prometheus decides to steal the secret of fire from the gods, Zeus becomes infuriated and decides to punish humankind with an "evil thing for their delight". This "evil thing" is Pandora, the first woman, who carried a jar (usually described—incorrectly—as a box) which she was told to never open. Epimetheus (the brother of Prometheus) is overwhelmed by her beauty, disregards Prometheus' warnings about her, and marries her. Pandora cannot resist peeking into the jar, and by opening it she unleashes into the world all evil; labour, sickness, old age, and death.Buddhism

In his book The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, professor Bernard Faure of Columbia University argued generally that "Buddhism is paradoxically neither as sexist nor as egalitarian as is usually thought." He remarked, "Many feminist scholars have emphasized the misogynistic (or at least androcentric) nature of Buddhism" and stated that Buddhism morally exalts its male monks while the mothers and wives of the monks also have important roles. Additionally, he wrote:While some scholars see Buddhism as part of a movement of emancipation, others see it as a source of oppression. Perhaps this is only a distinction between optimists and pessimists, if not between idealists and realists... As we begin to realize, the term "Buddhism" does not designate a monolithic entity, but covers a number of doctrines, ideologies, and practices--some of which seem to invite, tolerate, and even cultivate "otherness" on their margins.

Christianity

Eve rides astride the Serpent on a capital in Laach Abbey church, 13th century

Differences in tradition and interpretations of scripture have caused sects of Christianity to differ in their beliefs with regard their treatment of women.

In The Troublesome Helpmate, Katharine M. Rogers argues that Christianity is misogynistic, and she lists what she says are specific examples of misogyny in the Pauline epistles. She states:

The foundations of early Christian misogyny — its guilt about sex, its insistence on female subjection, its dread of female seduction — are all in St. Paul's epistles.In K. K. Ruthven's Feminist Literary Studies: An Introduction, Ruthven makes reference to Rogers' book and argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was consolidated by the so-called 'Fathers' of the Church, like Tertullian, who thought a woman was not only 'the gateway of the devil' but also 'a temple built over a sewer'."

However, some other scholars have argued that Christianity does not include misogynistic principles, or at least that a proper interpretation of Christianity would not include misogynistic principles. David M. Scholer, a biblical scholar at Fuller Theological Seminary, stated that the verse Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus") is "the fundamental Pauline theological basis for the inclusion of women and men as equal and mutual partners in all of the ministries of the church." In his book Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute, Richard Hove argues that—while Galatians 3:28 does mean that one's sex does not affect salvation—"there remains a pattern in which the wife is to emulate the church's submission to Christ (Eph 5:21-33) and the husband is to emulate Christ's love for the church."

In Christian Men Who Hate Women, clinical psychologist Margaret J. Rinck has written that Christian social culture often allows a misogynist "misuse of the biblical ideal of submission". However, she argues that this a distortion of the "healthy relationship of mutual submission" which is actually specified in Christian doctrine, where "[l]ove is based on a deep, mutual respect as the guiding principle behind all decisions, actions, and plans". Similarly, Catholic scholar Christopher West argues that "male domination violates God's plan and is the specific result of sin".

Islam

The fourth chapter (or sura) of the Quran is called "Women" (An-Nisa). The 34th verse is a key verse in feminist criticism of Islam. The verse reads: "Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great."In his book Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh, Taj Hashmi discusses misogyny in relation to Muslim culture (and to Bangladesh in particular), writing:

[T]hanks to the subjective interpretations of the Quran (almost exclusively by men), the preponderance of the misogynic mullahs and the regressive Shariah law in most "Muslim" countries, Islam is synonymously known as a promoter of misogyny in its worst form. Although there is no way of defending the so-called "great" traditions of Islam as libertarian and egalitarian with regard to women, we may draw a line between the Quranic texts and the corpus of avowedly misogynic writing and spoken words by the mullah having very little or no relevance to the Quran.In his book No god but God, University of Southern California professor Reza Aslan wrote that "misogynistic interpretation" has been persistently attached to An-Nisa, 34 because commentary on the Quran "has been the exclusive domain of Muslim men".

Sikhism

Guru Nanak in the center, amongst other Sikh figures

Scholars William M. Reynolds and Julie A. Webber have written that Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith tradition, was a "fighter for women's rights" that was "in no way misogynistic" in contrast to some of his contemporaries.

Scientology

In his book Scientology: A New Slant on Life, L. Ron Hubbard wrote the following passage:A society in which women are taught anything but the management of a family, the care of men, and the creation of the future generation is a society which is on its way out.In the same book, he also wrote:

The historian can peg the point where a society begins its sharpest decline at the instant when women begin to take part, on an equal footing with men, in political and business affairs, since this means that the men are decadent and the women are no longer women. This is not a sermon on the role or position of women; it is a statement of bald and basic fact.These passages, along with other ones of a similar nature from Hubbard, have been criticised by Alan Scherstuhl of The Village Voice as expressions of hatred towards women. However, Baylor University professor J. Gordon Melton has written that Hubbard later disregarded and abrogated much of his earlier views about women, which Melton views as merely echoes of common prejudices at the time. Melton has also stated that the Church of Scientology welcomes both genders equally at all levels—from leadership positions to auditing and so on—since Scientologists view people as spiritual beings.

Misogynistic ideas among prominent western thinkers

Numerous influential Western philosophers have been expressed ideas that can be characterized as misogynistic, including Aristotle, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G. W. F. Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, Otto Weininger, Oswald Spengler, and John Lucas. Because of the influence of these thinkers, feminist scholars trace misogyny in western culture to these philosophers and their ideas.Aristotle

Aristotle believed women were inferior and described them as "deformed males". In his work Politics, he statesas regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject 4 (1254b13-14).Another example is Cynthia's catalog where Cynthia states "Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity'. Aristotle believed that men and women naturally differed both physically and mentally. He claimed that women are "more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive ... more compassionate[,] ... more easily moved to tears[,] ... more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike[,] ... more prone to despondency and less hopeful[,] ... more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, of more retentive memory [and] ... also more wakeful; more shrinking [and] more difficult to rouse to action" than men.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is well known for his views against equal rights for women for example in his treatise Emile, he writes: "Always justify the burdens you impose upon girls but impose them anyway... . They must be thwarted from an early age... . They must be exercised to constraint, so that it costs them nothing to stifle all their fantasies to submit them to the will of others." Other quotes consist of "closed up in their houses", "must receive the decisions of fathers and husbands like that of the church".Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin wrote on the subject female inferiority through the lens of human evolution. He noted in his book The Descent of Men: "young of both sexes resembled the adult female in most species" which he extrapolated and further reasoned "males were more evolutionarily advanced than females". Darwin believed all savages, children and women had smaller brains and therefore led more by instinct and less by reason. Such ideas quickly spread to other scientists such as Professor Carl Vogt of natural sciences at the University of Geneva who argued "the child, the female, and the senile white" had the mental traits of a "grown up Negro", that the female is similar in intellectual capacity and personality traits to both infants and the "lower races" such as blacks while drawing conclusion that women are closely related to lower animals than men and "hence we should discover a greater apelike resemblance if we were to take a female as our standard". Darwin's beliefs about women were also reflective of his attitudes towards women in general for example his views towards marriage as a young man in which he was quoted ""how should I manage all my business if obligated to go everyday walking with my wife – Ehau!" and that being married was "worse than being a Negro". Or in other instances his concern of his son marrying a woman named Martineau about which he wrote "... he shall be not much better than her "nigger." Imagine poor Erasmus a nigger to so philosophical and energetic a lady ... Martineau had just returned from a whirlwind tour of America, and was full of married women's property rights ... Perfect equality of rights is part of her doctrine...We must pray for our poor "nigger.""Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer has been noted as a misogynist by many such as the philosopher, critic, and author Tom Grimwood. In a 2008 article Grimwood wrote published in the philosophical journal of Kritique, Grimwood argues that Schopenhauer's misogynistic works have largely escaped attention despite being more noticeable than those of other philosophers such as Nietzsche. For example, he noted Schopenhauer's works where the latter had argued women only have "meagre" reason comparable that of "the animal" "who lives in the present". Other works he noted consisted of Schopenhauer's argument that women's only role in nature is to further the species through childbirth and hence is equipped with the power to seduce and "capture" men. He goes on to state that women's cheerfulness is chaotic and disruptive which is why it is crucial to exercise obedience to those with rationality. For her to function beyond her rational subjugator is a threat against men as well as other women, he notes. Schopenhauer also thought women's cheerfulness is an expression of her lack of morality and incapability to understand abstract or objective meaning such as art. This is followed up by his quote "have never been able to produce a single, really great, genuine and original achievement in the fine arts, or bring to anywhere into the world a work of permanent value". Arthur Schopenhauer also blamed women for the fall of King Louis XIII and triggering the French Revolution, in which he was later quoted as saying:"At all events, a false position of the female sex, such as has its most acute symptom in our lady-business, is a fundamental defect of the state of society. Proceeding from the heart of this, it is bound to spread its noxious influence to all parts."

Schopenhauer has also been accused of misogyny for his essay "On Women" (Über die Weiber), in which he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico-Christian stupidity" on female affairs. He argued that women are "by nature meant to obey" as they are "childish, frivolous, and short sighted". He claimed that no woman had ever produced great art or "any work of permanent value". He also argued that women did not possess any real beauty:

It is only a man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulse that could give the name of the fair sex to that under-sized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race; for the whole beauty of the sex is bound up with this impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful there would be more warrant for describing women as the unaesthetic sex.

Nietzsche

In Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche stated that stricter controls on women was a condition of "every elevation of culture". In his Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he has a female character say "You are going to women? Do not forget the whip!" In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche writes "Women are considered profound. Why? Because we never fathom their depths. But women aren't even shallow." There is controversy over the questions of whether or not this amounts to misogyny, whether his polemic against women is meant to be taken literally, and the exact nature of his opinions of women.Hegel

Hegel's view of women can be characterized as misogynistic. Passages from Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right illustrate the criticism:Women are capable of education, but they are not made for activities which demand a universal faculty such as the more advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production... Women regulate their actions not by the demands of universality, but by arbitrary inclinations and opinions.

Academics who study misogyny

Kate Manne

Kate Manne is an analytic philosopher, assistant professor of philosophy at Cornell University, and author of Down Girl, the Logic of Misogyny. In her book, she argues that the tendency to treat misogyny as an individual character flaw is a "naive conception". She writes that misogyny is a cultural phenomenon that enforces gender norms and the policing of women's behavior. Moira Weigel writes of Manne's book:Manne goes on to elaborate the gender norms that misogyny enforces. We exist in a gendered economy in which women are assumed to owe men. The rules are: first, we must give men moral goods – such as sex, care and unpaid housework. Second, we must not ask men for the kinds of goods we give. Finally, women are not supposed to take masculine coded perks and privileges. (The presidency, for instance.) Manne proposes that sexism and misogyny are distinct. Sexism is an ideology, a set of beliefs, holding that it is natural, and therefore desirable, for men and women to perform these taking and giving roles. Misogyny functions like a "police force", punishing women who deviate from them. Generally, this police force also rewards obedience – elevating women who advance patriarchal interests. But because it defines women in terms of a giving function, misogyny also tends to treat women as interchangeable. In order to take revenge on female classmates he felt had spurned him, Rodger set out to kill strangers – most of them sexually active males.In other words, misogyny is not an individual character flaw. It is the way in which cultures keep women in subservient stations and positions within any given society.

Online misogyny

Misogynistic rhetoric is prevalent online and has grown rhetorically more aggressive. The public debate over gender-based attacks has increased significantly, leading to calls for policy interventions and better responses by social networks like Facebook and Twitter.A 2016 study conducted by the think tank Demos concluded that 50% of all misogynistic tweets on Twitter come from women themselves.

Most targets are women who are visible in the public sphere, women who speak out about the threats they receive, and women who are perceived to be associated with feminism or feminist gains. Authors of misogynistic messages are usually anonymous or otherwise difficult to identify. Their rhetoric involves misogynistic epithets and graphic and sexualized imagery, centers on the women's physical appearance, and prescribes sexual violence as a corrective for the targeted women. Examples of famous women who spoke out about misogynistic attacks are Anita Sarkeesian, Laurie Penny, Caroline Criado Perez, Stella Creasy, and Lindy West.

The insults and threats directed at different women tend to be very similar. Sady Doyle who has been the target of online threats noted the "overwhelmingly impersonal, repetitive, stereotyped quality" of the abuse, the fact that "all of us are being called the same things, in the same tone".

Evolutionary theory

A 2015 study published in the journal PLOS ONE by researchers Michael M. Kasomovic and Jefferey S. Kuznekoff found that male status mediates sexist behavior towards women. The study found that women tend to experience hostile and sexist behavior in a male dominated field by lower status men. According to the theory proposed by the authors, since male dominated groups tend to be organized in hierarchies, the entry of women re-arranges the hierarchy in their favor by attracting the attention of higher status men. This, the theory goes, enables women automatic higher status over lower rank men, which is responded to by lower status men using sexist hostility in order to control for status loss. This study was one of the first notable pieces of evidence of inter-gender competition and has possible evolutionary implications for the origin of sexism.Psychological impact

Internalized misogyny

Internalized sexism is when an individual enacts sexist actions and attitudes towards themselves and people of their own sex. On a larger scale, internalized sexism falls under the broad topic of internalized oppression, which "consists of oppressive practices that continue to make the rounds even when members of the oppressor group are not present". Women who experience internalized misogyny may express it through minimizing the value of women, mistrusting women, and believing gender bias in favor of men. Women, after hearing men demean the value and skills of women repeatedly, eventually internalize their beliefs and apply the misogynistic beliefs to themselves and other women. A common manifestation of internalized misogyny is lateral violence.As a hate crime

The Nottinghamshire Police in 2016 was "the first force in the country to recognize misogyny as a hate crime", applying to "incidents ranging from street harassment to physical intrusions on women's space." "In the first year, 97 incidents were recorded. This milestone achievement arose from work by Nottingham Women's Centre and Nottingham Citizens. Thanks to [Nottinghamshire's] police force listening to local women's organisations, women and girls in Nottingham will receive the message that this kind of behaviour isn't normal or acceptable, that support is available, and that the problem will be taken seriously." —Laura Bates, The Everyday Sexism Project.On 7 March 2018 a debate that had the title "misogyny as a hate crime" was held in Westminster Hall and at the end of the debate hansard states that: "Question put and agreed to. Resolved, That this House has considered misogyny as a hate crime."

A research briefing paper was placed in the House of Commons library on 6 March 2018 and two parts of it, "police recording practices" and "recent calls for change", are quoted in the following paragraphs:

- "Police recording practices: For example, in 2016 Nottinghamshire Police began recording misogynistic hate crime. The change, which was initially a two month experiment in July and August 2016, is still in place at Nottinghamshire Police, with the success of the trial drawing national interest from other police forces. Giving evidence to the Home Affairs Committee in February 2017, Assistant Chief Constable Mark Hamilton, National Policing Lead for Hate Crime, said that five police forces tracked misogyny-based hate crime, but that no national consensus had yet been reached. In December 2017, ACC Mark Hamilton gave evidence to the Women and Equalities Committee in which he provided a further update. He said that the police are still looking nationally at the idea of recording misogyny as a hate crime, but that if the police move forward with this they will be looking for it to be supported by legislative action on enhanced sentencing."

- "Recent calls for change: At a meeting in March 2017, the APPG, all-party parliamentary group, on Domestic Violence looked at misogyny as a hate crime, with a particular focus on police recording practices. There was a 'clear consensus' from those present that the Nottinghamshire Police policy had been 'an important step forward for tackling street harassment and abuse, and challenging wider sexism and objectification of women in society'. However, the meeting acknowledged that there were barriers to adopting the policy within police forces, 'including rising demand and decreasing resources, the increasing complexity of tackling modern crime, and reputational and public relations issues'. There was also some concern that if the policy were to be adopted nationally, it might need to be framed as "gender based hate crime" rather than misogyny because of 'a view that men should be treated equally under the law'. The APPG considered that this might be problematic, as it would 'fail to address misogyny as a structural problem, and could lead to widespread reporting of misandry, when in reality it is very rare indeed for men to be victims of hate crime because of their gender specifically'."

- "In January 2017 the Fawcett Society launched a Sex Discrimination Law Review, which involved an expert panel reviewing a number of sex discrimination issues including hate crime. The Panel published its final report in January 2018, which included the following recommendations on hate crime:

- Hate crime should be 'misogyny' hate crime, not gender hate crime, recognising 'the direction of the power imbalance within society'. The Fawcett Society said that this would be 'consistent with the one-directional nature of transgender or disability hate crime'.

- All police forces should be required to recognise misogyny as a hate crime for recording purposes.

- Legislation should be introduced to establish misogyny as a hate crime for enhanced sentencing purposes."