From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_monarchy

A universal monarchy is a concept and political situation where one monarchy is deemed to have either sole rule over everywhere (or at least the predominant part of a geopolitical area or areas) or to have a special supremacy over all other states (or at least all the states in a geopolitical area or areas).

Concept

Universal monarchy is differentiated from ordinary monarchy in that a universal monarchy is beholden to no other state and asserts a degree of total sovereignty over an area, or predominance over other states.

The concept has arisen in Egypt, Europe, Asia and Peru. The concept is linked to that of Empire, but implies more than simply possessing imperium.

The Latin phrase Dominus Mundi, Lord of the World, encapsulates the concept. Though in practice no universal monarchy, or indeed any state, ever held rule over the whole world, it may have appeared to many people, particularly pre-modern, that it did.

Critical of the concept in Europe in the Middle Ages were philosophers such as Nicole Oresme and Erasmus; whereas Guillaume Postel was more favourable and Dante was a convinced adherent. Later, Protestants would seek to reject the concept, identifying it with Catholicism.

History

Egypt and Mesopotamia

For the ancient Egyptians, four directions of the world were regarded as “united in one head” of king. Ramses III was presented as the “commander of the whole land united in one.” Except the Amarna period, Egypt’s official ideology did not recognize coexistence of two or more kings. “The monarchy in Egypt constituted a unity, a single fraction, with universal application.” The Hymn of Victory of Thutmose III and the Stelae of Amenophis II proclaimed: “There is no one who makes a boundary with him... There is no boundary for him towards all lands united, towards all lands together.” Thutmos III was acknowledged: “None presents himself before thy majesty. The circuit of the Great Circle [Ocean] is included in thy grasp.” Asiatic kings recognized Tutankhamen: “There is none living in ignorance of thee.”

The King was believed to be Son of the Sun and to rule all under the sun. The ascent of a king was associate with sunrise. The same verb “dawned” was used for the ascent of king and the rising of the sun. On Abydos Stelae, Thutmose I claimed: "I made the boundaries of Egypt as far as the sun encircles... Shining like Ra... forever." The sun symbolized universality both in space and time. The Story of Sinuke expresses both: May all the gods “give you eternity without limits, infinity without bonds! May the fear of you resound in lowlands and highlands, for you have subdued all that the sun encircles.”

The genre of King list also illustrates the universality of monarchy. Introduced into the Egyptian tradition in the reign of Unas (2385-2355 BC) of the Fifth Dynasty, the ideological purpose of the genre was to stress the royal universality as the only legitimate king stretching back in an unbroken succession to the time of gods.

The contemporary Mesopotamian civilization had much weaker tradition of universal monarchy but it also developed a King list with the same ideological purpose to stress the royal universality as the only legitimate king stretching back in an unbroken succession to the time of gods. Mesopotamian kings did not claim to rule all what the sun encircles, but they did claim to be "King of the Four Corners" of the world and "King of the inhabited world."

Europe

In Europe, the expression of a Universal Monarchy as actual total imperium can be seen in the Roman Empire, and as the predominant ‘sole sovereign’ state during its Byzantine period, where the emperor by virtue of being the head of Christendom claimed sovereignty over all other kings even though in practice this could not be enforced. The Byzantine conception went through two phases, initially as expounded by Eusebius that just as there was one God so there could only be one Emperor, which developed in the 10th century into the conception of the Emperor as the paterfamilias of a family of kings who were the other rulers in the world. Such concepts were a feature of the Ottoman Empire's successor state, particularly when military rule was augmented by the Caliphate.

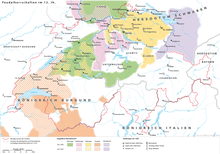

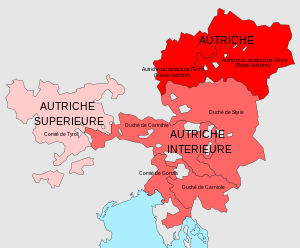

The idea of a sole sovereign emperor would re-emerge in the West with Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire. The idea of the Holy Roman Empire possessing special sovereignty as a Universal Monarchy was respected by the surrounding powers and subject states, even when that Empire had undergone severe fragmentation. The symbolism of the "All the world is subject to Austria" (A.E.I.O.U.) phrase of Frederick III can be seen as an expression of the idea of all states being subject to one monarchy. The medieval hierocrats, on the other hand, argued that the pope was a universal monarch.

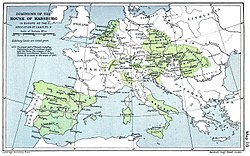

Charles V's empire, encompassing much of western Europe and the Americas "was the nearest the post-classical world would come to seeing a truly worldwide monarchy, and hence the closest approximation to universal imperium." It was envisaged by its supporters as a world empire that could be religiously inclusive.

Subsequently, the idea of a Universal Monarchy based on predominance rather than the actual total rule would become synonymous with France attempting to establish hegemony over western Europe, particularly under Louis XIV, exemplified by the concept of Louis XIV as the 'Sun King' around which all the other monarchs became subordinate satellites. In 1755, during the reign of Louis XIV's successor Louis XV, Duke Adrien Maurice de Noailles, a member of the Council of State and formerly a key foreign policy advisor to the king, warned of a British challenge for "the first rank in Europe" through the domination of Atlantic commerce. Noailles wrote, "However chimerical the project of universal monarchy might be, that of a universal influence by means of wealth would cease to be a chimera if a nation succeeded in making itself sole mistress of the trade of America."

Monarchy would be strong in Russia. The Russian Monarchy was Orthodox, autocratic, and possessed a vast contiguous empire throughout Europe and Asia and can be seen to have similarities and differences with Byzantine rule. The British Monarchy was "Protestant, commercial, maritime and free" and was not composed of contiguous territory. It had both similarities and differences with the Spanish Empire. Both were "Empire on which the sun never sets." While Catholicism provided ideological unity for the Spanish Empire, British Protestant diversity would lead to "disunity rather than unity". It was only later that federalism and economic control were seen as a means to provide unity where religious diversity could not, as with the idea of an Imperial Federation as promoted by Joseph Chamberlain.

Napoleon came close to creating something akin to a Universal Monarchy with his continental system and Napoleonic Code, but he failed to conquer all of Europe. Following the battle of Jena when Napoleon overwhelmed Prussia, it seemed to Fichte that the universal monarchy was inevitable and close at hand. He found a “necessary tendency in every civilized state” to expand and traced this tendency to Antiquity. An “invisible” historical spirit runs through all epochs and urges states onward. “As the States become stronger in themselves... the tendency towards a Universal Monarchy over the whole Christian World necessarily comes to light.” The last attempt to create a European Universal Monarchy was that attempted by Imperial Germany in World War I. If Germany is victorious, thought Woodrow Wilson in 1917, the German Kaiser would have been suzerain over most of Europe...

East Asia

A similar phenomenon occurred in China. "The Son of Heaven" emerged during the Zhou dynasty. The title denotes universality - ruling All under Heaven. The Book of Odes said:

Beneath all heaven

There is no land that is not the king’s;

Throughout the borders of the earth,

None who are not his subjects!

The title also denotes a higher, "heavenly" rule ("Celestial Empire"), in contrast to kings who rule between heaven and earth, and by extension today to presidents who are mere base earthly rulers. Imperial China, as well as Japan, was regarded by its citizens as a Universal Monarchy where all other monarchs were regarded as tributaries. In China this was exemplified in the Chinese name for the state which survives to this day, Zhongguo, meaning "Middle/Central Kingdom". Since the title Son of Heaven originated during the Zhou dynasty, the Chinese perceived universal monarchy as the only correct rule. During the centuries-long period of independent states (771-221 BC), none of the known thinkers tried to develop a concept of separate national identity or independence:

Yet, when we examine the writing of the hundred schools of the [later] Zhou period, we are forcefully struck by the ongoing tenacious hold of the ancient idea of universal kingship even during this period of division. No outlook emerges that is prepared to treat the multistate system as normative or normal... No Chinese Grotius or Puffendorf emerges.[

The inscription of the First Emperor of China said: “Wherever life is found, all acknowledge his suzerainty.” The Sinocentric paradigm survived until the 19th century. When George III (1780-1831) proposed them trading contacts, the Chinese declined, because "the Celestial Empire, ruling all within the four seas... does not have the slightest need of your country's manufactures." They added that George III must act in conformity with their wishes, strengthen his loyalty and swear perpetual obedience.

The Chinese concept of universal monarchy was taken up by the Mongols, who under Genghis Khan were able to enforce this concept more widely than China. The Chinese Son of Heaven also contributed to a counterpart in Japan, but in some aspects, the Japanese made their monarchy more universal. The Chinese emperor was bound to the Mandate of Heaven. No such mandate existed for Tenno. Descended from the Sun goddess Amaterasu in the immemorial past, one Dynasty is supposed to rule Japan forever. The Chinese ended their dynastic cycle in 1911; the Japanese Dynasty continues until the present day and today is the oldest active dynasty in the world, albeit Douglas MacArthur undeified it in 1945.

The Hindu/Buddhist concept of the Chakravartin is a perfect illustration of the ideal of a Universal Monarch.

The Islamic world

In Sunni Islam, the concept of the Caliphate can be considered a universal monarchy. Crucially, the Caliph is not necessarily a spiritual leader; rather, he is the secular head of the Muslim community and is (theoretically) bound by and subject to Islamic law. The word Khalifah can be translated variously as successor, steward, deputy, or viceregent, with the implication that the Caliph is the worldly successor to the Prophet Muhammad (and importantly is not his spiritual successor; as Muhammad is considered to be the last prophet, Sunni Muslims hold that he can have no spiritual successor). The duties of the Caliph, in theory, include the administration of Islamic law; the enactment of policies for the welfare of Muslims; the custodianship of Islamic holy sites and care of pilgrims; the custodianship of conquered non-Muslims and mediation of their interests relative to those of Muslims; the prosecution of holy wars (both offensive and defensive); and the representation of the diplomatic interests of the global Muslim community, even beyond the borders of the Caliphate's domains (a precedent set during Muhammad's life, with respect to the early Islamic community in Ethiopia).

In Shia Islam, the concept of the Imamate is comparable to the Sunni Caliphate, but it is not identical. The Shia Imam is considered to be both the spiritual and the secular leader of the global Muslim community; therefore, the Imam not only holds authority over policy and administration but is also the infallible final arbiter in the interpretation of law and theology. However, like the Sunni caliph, the Shia imam's authority as a monarch is considered universal. The Imamate is tied to the Ahl al-Bayt; dynasties that claim the Imamate also claim descent from Muhammad via Ali and Fatimah, and pass the title of Imam down from father to son, with different Shia denominations following different lineages. For example, the Twelver Shia Muslims follow the line of the Twelve Imams, of whom the last has supposedly been in occultation since the 9th century CE; however, the Nizari Shia Muslims follow a different and still-living line of Imams, of whom the Agha-Khan IV is the current head.

Inca

In the Americas, the Inca monarchy was universal in the sense of a sole rule over the whole contemporary geopolitical area, around which were only unsettled societies. The Inca people called their state the “realm of the four quarters of the world.”), a concept of universality in space analogous to “four quarters” of other universal monarchies. As the Chinese called their country “Country in the middle,” the Incas called their capital, Cusco, “the navel of the world.”. This civilization did not develop writing, but the Spanish reports and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega tell that the Inca monarchy was one of the most absolute and divine in history.

Inca “was respected as god.”. As the kings of Egypt and Japan, the Inca were Sons of the Sun. And as the Egyptian kings, the Inca were mummified and worshipped as gods by subsequent generations. Their names, like Viracocha Inca, also imply their divinity and Burr Cartwright Brundage associated the above name with the Near Eastern concept of King of Kings. The title of the Incas, Sapa Inca (=the “Only Emperor”), implied that no other emperor could exist anywhere in the world. The Inca oral tradition preserved a King list, an ideological genre of universal monarchies implying the universality in time and space. The Inca were of divine origins. Like the founder of the Japanese Dynasty, the Inca founder, Manco Capac was the son of the god Sun.

Features

Cosmopolitanism

Universal monarchies were the cradle of cosmopolitanism. The earliest in history concept that men of all colors are equal comes from ancient Egypt. The Great Hymn to the Aten dated during the reign of Akhenaten of the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1353–1336 BC) reads: The “tongues of peoples differ in speech, their characters likewise; their skins are distinct, for Aten distinguished the peoples.” But Aten cares for all of them. “In all lands of the world, you set every man in his place, you supply their need, everyone has his food...”

The Persian universal monarchs tolerated the cultures, languages, and religions of the subordinated peoples and supported local religious institutions. They ceased the mass deportations practiced by the previous Assyrian and Babylonian Empires, and allowed Jews to return from the Babylonian captivity to their land and restore their Temple.

Following the rise of the Maurya to a universal dynasty in India, Buddhism replaced Brahmanism as the dominant creed and challenged its strict caste hierarchy. Buddhism advocated cosmopolitan social and religious equality. However, the Mauryan universal monarchy was short-lived, and after its dissolution into independent kingdoms, Brahmanism made a comeback with Buddhism retreating to “underground survival” in India. Nevertheless, cosmopolitan Buddhism would find fertile soil in the universal monarchies of China and Japan.

Following the rise of Alexander the Great to the universal monarch, Stoicism became the dominant school of Hellenistic philosophy. The Stoics articulated a form of Greek citizenship that disrespected the walls of the polis hitherto thought to constrain human communities. Its founder, Zeno of Citium (c. 334 – c. 262 BC), advised that inhabitants of all poleis should form “one way of life and one order.” Stoics were radically cosmopolitan by contemporary standards and preached to accept even slaves as "equals of other men because all men alike are products of nature." Later Stoic thinker Seneca in his Letter exhorted, "Kindly remember that he whom you call your slave sprang from the same stock, is smiled upon by the same skies, and on equal terms with yourself breathes, lives, and dies." The Stoics held that external differences, such as rank and wealth, are of no importance in social relationships. Instead, they advocated the brotherhood of humanity and the natural equality of all human beings. According to the Stoics, all people are manifestations of the one universal spirit and should live in brotherly love and readily help one another. Stoicism became the foremost and most influential philosophy under the Hellenistic and Roman universal monarchs and often is called an official philosophy of the monarchy.

Through Paul the Apostle, Stoicism influenced the cosmopolitan revolution in Christianity. Paul decisively broke with the Judaist xenophobia and opened the new religion to all humanity. The Chosen people were no longer ethnically defined. Combining the Stoic ideal with Christ, Paul called Christ-followers to embrace the ideal of a single humanity living in harmony with a divinely ordered cosmos. Hitherto reserved to the Jews, salvation became available to the Gentiles. A book titled Cosmopolitanism and Empire: Universal Rulers... and Cultural Integration in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, concludes: The cosmopolitanisms which emerged in the concerned regions in the Axial Age were products of universal monarchies.

Under the universal monarchy on the other side of Tibet, cosmopolitanism flourished too. The Tang dynasty saw the influx of thousands of foreigners who came to live in Chinese commercial hub cities. Expatriates spilled in from all over Asia and beyond, with a bounty of people from Persia, Arabia, India, Korea, and Southeast and Central Asia. Chinese cities became bustling epicenters of commerce and trade, abundant in foreign residents and the plethora of cultural riches that they brought with them. A census taken in 742 AD showed that the foreign proportion of the registered population had massively increased from nearly a quarter in the early seventh century to nearly half by the mid seventh century, with an estimated 200,000 foreigners in residence in Canton alone. Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism were practiced undisturbed in China, as well as in Japan, where the three coexisted with Shinto.

Pacifism

Contrary to the warlike civilizations of independent kingdoms, universal monarchies were pacifist. Each universal monarchy generated a kind of Pax Romana and preached the benefits of peace over the glory of war. Universal monarchs claimed to pacify rather than conquer. The Romans derived from the word “pax” (peace) verb “pacare,” meaning to pacify. The first Roman universal monarch, following his victory, established the Arc of Peace (Ara Pacis Augustae) instead of the arc of triumph.

No heroic epic is known from the civilizations of Egypt and China. Egyptian and Chinese heroes were sages and inventors. Herodotus noted that the Egyptians “are not accustomed to pay any honors to heroes.” “No epic narrative spanned past generations, no tale of destiny urged a moral on the living.” Universal monarchs preferred prosaic narrative. According to the Egyptian records, universal monarchy was the way to universal peace: "when the gods inclined to peace," they decided to "establish their Son... to be ruler of every land."

In China the first universal monarch of the post-Warring States period “confiscated the weapons of the world, collected them together... and [at a great banquet] smelt them into bells and bell-racks, as well as twelve bronze statues...” Peace became the feature of the Chinese world, as Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330 – 400 AD) noted in one of the earliest external accounts: “The Seres [=Chinese] themselves live a peaceful life, forever unacquainted with arms and warfare; and since to gentle and quite folk ease is pleasurable, they are troublesome to none of their neighbors.” In 1637, Jesuit Giulio Alenio reported that he was often asked by his Chinese friends: “If there are so many kings, how can you avoid wars?” It was a good question in the middle of the frightful Thirty Years’ War.

Due to its pacifism, the Inca universal monarchy was defeated by the Spaniards within “scarcely three hours,” by a force outnumbered 1 to 45 and without a single Spaniard killed. The Azteca monarchy, which was not universal, stands in sharp contrast despite the same disadvantage in military technology. The last independent Mexica tlatoani, Cuauhtémoc, held a fierce defense of Tenochtitlan for 80 days, forced Hernán Cortés to mobilize tens of thousands of Indian allies and impressed him with valor.

Divinity

Generally, comparative historical research on monarchies finds that universal monarchs were more absolute and divine than the modern European absolute kings. The ideologies of modern absolute monarchies claimed the monarch to be subject to divine, not human, law. “But he was no ancient emperor; he was not the sole source of law; of coinage, weights and measures; of economic monopolies... He owned only his own estates.” “In his person Augustus accumulated the pillars of power: armed forces, control of the elite, wealth and patronage of the public clientelae. That is why Augustus, perhaps more than Louis XIV, would have been entitled to say: L’etat, c’est moi.”

The Egyptian and Inca kings were mummified and worshipped for generations as gods (chapters on Egypt and Inca above). The Egyptian royal tombs – pyramids – is perhaps the best expression of the level of veneration. Notably, with the rise of universal monarchs in Japan, impressive megalithic tombs covered their land. Egyptologists debate whether the Son of the Sun was above or below the gods; Sinologists and Japanologists agree that their Sons of Heaven were above the gods and similar to the status of God in Abrahamic religions.

A divinity threshold was crossed the moment of universal conquest. Following the Qin universal conquest in 221 BC, the First Emperor of the universal realm was titled "Huang," meaning "August," and "Di," or "Divine." Sima Qian explicitly states the causal link between thr universal conquest and divinity. The Inca ruler, with the establishment of his universal monarchy, changed his royal "Capac" title, somewhat equivalent of "Duke," for the divine name by which he was thereafter known to history, "Viracocha Inca."

Following another universal conquest, Alexander the Great broke with much of the Macedonian royal tradition, where kings were mortal like the rest of humans. Alexander and his successors became divine and some added to their names "Epiphanes," meaning "Divine."

Augustus is another word for "Divine," and Augustus' image reminds that of Jesus. Calendar Inscription of Priene (9 BC) uses the term "gospel" referring to him and describes him as "Savior" and "God manifest." Augustus "had wiped away our sins" shortly before Jesus did it again. Augustus' less fortunate predecessor, having crossed the Rubicon toward the universal monarchy, became "Divus" and traced his origins to Venus.

Monotheism

The rise of extremely absolute and divine personality on earth triggered a similar process in Heaven. Main gods rose to more universal and transcendent status and on several occasions universal monarchies generated monotheism. Akhenaten undertook the earliest know attempt, albeit short-lived. The Great Hymn to the Aten is the earliest in world history record to proclaim God as "sole" beside Whom there is "none." Beginning with Sargon II, Assyrian scribes began to write the name of Ashur (god) with the ideogram for "whole heaven." According to Simo Parpola, the Neo-Assyrian empire developed a complete monotheism.

The Assyrian case is crucial regarding Judaism — the only ancient monotheism which is not a product of universal monarchy. Notably, the Jewish religion became monotheist in the Babylonian captivity. One hypothesis maintains that the Jewish priests adopted the local monotheism and replaced Ashur with Yahweh. The Assyrian monotheist concept of “(all) the gods” was translated into Hebrew as Elohim, literally “(all) the gods.” This explains the puzzle of Psalm 46:4-5 with God dwelling in his City on the river. There is no river in Jerusalem. The City of Assur was on the river. “Yahweh’s emergence as a major player on the divine scene mirrored those of... Marduk and Assur.” The former, as Yahweh, had a temple without an image to express his monotheist nature. Some scholars also supposed the influence of the Egyptian universal monarchy, particularly of the Great Hymn to the Aten on Psalm 104.

Synchronously with Judaism, the Persian universal monarchy elaborated Zoroastrianism considered by most as monotheistic. Eventually, two most popular monotheist legacies of universal monarchies became Christianity and Islam.

Vision of history

For ancient Egypt, China, Japan and Inca, the beginning of history was marked by the emergence of universal monarchy. This event in terms of their traditions originated during the time these people saw as what we would call prehistory. Universal monarchies lacked linear, teleological, utopian or progressive vision of history of the Western kind. For them, the ideal state is not in an utopian future but a historic past and no further progress was even theoretically possible. All what was needed ever since the rise of universal monarchy was to maintain it, and if lost, restore it as soon as possible. Thus history acquired cyclical pattern.

German Sociologist Friedrich Tenbruck, criticizing the Western idea of progress, emphasized that China and Egypt remained at one particular stage of development for millennia. This stage was universal monarchy. The development of Egypt and China came to a halt once their empires "reached the limits of their natural habitat," that is, became universal.

Periods when monarchies were more universal – Shang, Zhou, Han and Tang dynasties in China, Gupta and Mughal dynasties in India, the Heian Japan, the Augustan and Antonine Rome – were remembered by posterity as “Golden Ages.” Edward Gibbon described the Antonine age as best in human history. The Islamic Golden Age also begins during the universal Abbasid dynasty. The Spanish, Portuguese and British Golden Ages similarly coincide with periods when their monarchies came closest to universal.

Seeing the ideal model in the past, most universal monarchies had a greater concern with history than their non-universal colleagues did. The difference is striking comparing the volumes of historical records of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, China and India, or Rome and the post-Roman Europe. Not always, but as a rule, the more monarchy is universal in space and lasting in time, the more history it writes.

Regarding future, universal monarchies are prominent in their optimism. They did not expect apocalypse or cosmic recycling, nor even lesser disasters like destructive warfare or imperial fall characteristic for Mesopotamian and Hebrew prophetic literature. Instead, they believed in eternal orderly existence. Those monarchies were deemed universal in both space and time. In Japan even dynasties were not supposed to rise and fall. One dynasty was believed to ever last. Gods provided the Egyptian kings with “eternity without limits, infinity without bounds.” A great culture of eternity evolved. The pyramids, mummies and Terracotta Army were designed to last forever.