From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Recent human evolution refers to evolutionary adaptation, sexual and natural selection, and genetic drift within Homo sapiens populations, since their separation and dispersal in the Middle Paleolithic

about 50,000 years ago. Contrary to popular belief, not only are humans

still evolving, their evolution since the dawn of agriculture is faster

than ever before. It is possible that human culture—itself a selective force—has accelerated human evolution.

With a sufficiently large data set and modern research methods,

scientists can study the changes in the frequency of an allele occurring

in a tiny subset of the population over a single lifetime, the shortest

meaningful time scale in evolution.

Comparing a given gene with that of other species enables geneticists

to determine whether it is rapidly evolving in humans alone. For

example, while human DNA is on average 98% identical to chimp DNA, the

so-called Human Accelerated Region 1 (HAR1), involved in the development of the brain, is only 85% similar.

Following the peopling of Africa some 130,000 years ago, and the recent Out-of-Africa expansion some 70,000 to 50,000 years ago, some sub-populations of Homo sapiens have been geographically isolated for tens of thousands of years prior to the early modern Age of Discovery. Combined with archaic admixture, this has resulted in significant genetic variation, which in some instances has been shown to be the result of directional selection taking place over the past 15,000 years, which is significantly later than possible archaic admixture events.

That the human populations living on different parts of the globe have

been evolving on divergent trajectories reflects the different

conditions of their habitats. Selection pressures were especially severe for populations affected by the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) in Eurasia, and for sedentary farming populations since the Neolithic, or New Stone Age.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

(SNP, pronounced 'snip'), or mutations of a single genetic code

"letter" in an allele that spread across a population, in functional

parts of the genome can potentially modify virtually any conceivable

trait, from height and eye color to susceptibility to diabetes and

schizophrenia. Approximately 2% of the human genome codes for proteins

and a slightly larger fraction is involved in gene regulation. But most

of the rest of the genome has no known function. If the environment

remains stable, the beneficial mutations will spread throughout the

local population over many generations until it becomes a dominant

trait. An extremely beneficial allele could become ubiquitous in a

population in as little as a few centuries whereas those that are less

advantageous typically take millennia.

Human traits that emerged recently include the ability to

free-dive for long periods of time, adaptations for living in high

altitudes where oxygen concentrations are low, resistance to contagious

diseases (such as malaria), fair skin, blue eyes, lactase persistence

(or the ability to digest milk after weaning), lower blood pressure and

cholesterol levels, thick hair shaft, dry ear wax, lower chances of

drunkenness, higher body-mass index, reduced prevalence of Alzheimer's

disease, lower susceptibility to diabetes, genetic longevity, shrinking

brain sizes, and changes in the timing of menarche and menopause.

Archaic admixture

Genetic evidence suggests that a species dubbed Homo heidelbergensis is the last common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens.

This common ancestor lived between 600,000 and 750,000 years ago,

likely in either Europe or Africa. Members of this species migrated

throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Africa and became the

Neanderthals in Western Asia and Europe while another group moved

further east and evolved into the Denisovans, named after the Denisovan

Cave in Russia where the first known fossils of them were discovered. In

Africa, members this group eventually became anatomically modern

humans. Migrations and geographical isolation notwithstanding, the three

descendant groups of Homo heidelbergensis later met and interbred.

Reconstruction of a Neanderthal female.

DNA analysis reveals that modern-day Tibetans, Melanesians, and

Australian Aboriginals carry about 3%-5% of Denisovan DNA. In addition,

DNA analysis of Indonesians and Papua New Guineans indicates that Homo sapiens and Denisovans interbred as recently as between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago.

Archaeological research suggests that as prehistoric humans swept

across Europe 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals went extinct. Even so,

there is evidence of interbreeding between the two groups as humans

expanded their presence in the continent. While prehistoric humans

carried 3%-6% Neanderthal DNA, modern humans have only about 2%. This

seems to suggest selection against Neanderthal-derived traits.

For example, the neighborhood of the gene FOXP2, affecting speech and

language, shows no signs of Neanderthal inheritance whatsoever.

Introgression of genetic variants acquired by Neanderthal admixture has different distributions in Europeans and East Asians, pointing to differences in selective pressures. Though East Asians inherit more Neanderthal DNA than Europeans,

East Asians, South Asians, and Europeans all share Neanderthal DNA, so

hybridization likely occurred between Neanderthals and their common

ancestors coming out of Africa. Their differences also suggest separate hybridization events for the ancestors of East Asians and other Eurasians.

Following the genome sequencing of three Vindija Neanderthals, a

draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome was published and revealed that

Neanderthals shared more alleles with Eurasian populations—such as

French, Han Chinese, and Papua New Guinean—than with sub-Saharan African

populations, such as Yoruba and San. According to the authors of the

study, the observed excess of genetic similarity is best explained by

recent gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans after the migration out of Africa.

But gene flow did not go one way. The fact that some of the ancestors

of modern humans in Europe migrated back into Africa means that modern

Africans also carry some genetic materials from Neanderthals. In

particular, Africans share 7.2% Neanderthal DNA with Europeans but only

2% with East Asians.

Some climatic adaptations, such as high-altitude adaptation in humans, are thought to have been acquired by archaic admixture. An ethnic group known as the Sherpas from Nepal is believed to have inherited an allele called EPAS1, which allows them to breathe easily at high altitudes, from the Denisovans.

A 2014 study reported that Neanderthal-derived variants found in East

Asian populations showed clustering in functional groups related to immune and haematopoietic pathways, while European populations showed clustering in functional groups related to the lipid catabolic process. A 2017 study found correlation of Neanderthal admixture in modern European populations with traits such as skin tone, hair color, height, sleeping patterns, mood and smoking addiction.

A 2020 study of Africans unveiled Neanderthal haplotypes, or alleles

that tend to be inherited together, linked to immunity and ultraviolet

sensitivity. The promotion of beneficial traits acquired from admixture is known as adaptive introgression.

Upper Paleolithic, or the Late Stone Age (50,000 to 12,000 years ago)

Epicanthic eye folds are thought to be an adaptation for cold weather.

DNA analyses conducted since 2007 revealed the acceleration of

evolution with regards to defenses against disease, skin color, nose

shapes, hair color and type, and body shape since about 40,000 years

ago, continuing a trend of active selection since humans emigrated from

Africa 100,000 years ago. Humans living in colder climates tend to be

more heavily built compared to those in warmer climates because having a

smaller surface area compared to volume makes it easier to retain heat.

People from warmer climates tend to have thicker lips, which have large

surface areas, enabling them to keep cool. With regards to nose shapes,

humans residing in hot and dry places tend to have narrow and

protruding noses in order to reduce loss of moisture. Humans living in

hot and humid places tend to have flat and broad noses that moisturizes

inhaled hair and retains moisture from exhaled air. Humans dwelling in

cold and dry places tend to have small, narrow, and long noses in order

to warm and moisturize inhaled air. As for hair types, humans from

regions with colder climates tend to have straight hair so that the head

and neck are kept warm. Straight hair also allows cool moisture to

quickly fall off the head. On the other hand, tight and curly hair

increases the exposed areas of the scalp, easing the evaporation of

sweat and allowing heat to be radiated away while keeping itself off the

neck and shoulders. Epicanthic eye folds are believed to be an adaptation protecting the eye from the snow and reducing snow glare.

Physiological or phenotypical changes have been traced to Upper Paleolithic mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the EDAR

gene, dated to about 35,000 years ago. Traits affected by the mutation

are sweat glands, teeth, hair thickness and breast tissue.

While Africans and Europeans carry the ancestral version of the gene,

most East Asians have the mutated version. By testing the gene on mice,

Yana G. Kamberov and Pardis C. Sabeti and their colleagues at the Broad

Institute found that the mutated version brings thicker hair shafts,

more sweat glands, and less breast tissue. East Asian women are known

for having comparatively small breasts and East Asians in general tend

to have thick hair. The research team calculated that this gene

originated in Southern China, which was warm and humid, meaning having

more sweat glands would be advantageous to the hunter-gatherers who

lived there. Geneticist Joshua Akey suggested that the mutant gene could

also be favored by sexual selection in that the visible traits

associated with this gene made the individual carrying it more

attractive to potential mates. Yet a third explanation is offered by

Kamberov, who argued that each of the traits due to the mutant gene

could be favored at different times. Today, the mutant version of EDAR

can be found among 93% of the Han Chinese, 70% among the Japanese and

the Thai, and between 60% to 90% among the American Indians, who

descended from East Asia.

The most recent Ice Age peaked in intensity between 19,000 and

25,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. As the glaciers that

once covered Scandinavia all the way down to Northern France retreated,

humans began returning to Northern Europe from the Southwest, modern-day

Spain. But about 14,000 years ago, humans from Southeastern Europe,

especially Greece and Turkey, began migrating to the rest of the

continent, displacing the first group of humans. Analysis of genomic

data revealed that all Europeans since 37,000 years ago have descended

from a single founding population that survived the Ice Age, with

specimens found in various parts of the continent, such as Belgium.

Although this human population got displaced 33,000 years ago, a

genetically related group began spreading across Europe 19,000 years

ago. Recent divergence of Eurasian lineages was sped up significantly during the Last Glacial Maximum, the Mesolithic and the Neolithic, due to increased selection pressures and founder effects associated with migration. Alleles predictive of light skin have been found in Neanderthals, but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, KITLG and ASIP, are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations since the LGM. Phenotypes associated with the white or Caucasian

populations of Western Eurasian stock emerge during the LGM, from about

19,000 years ago. The light skin pigmentation characteristic of modern

Europeans is estimated to have spread across Europe in a "selective

sweep" during the Mesolithic (5,000 years ago). The associated TYRP1 SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 alleles emerge around 19,000 years ago, still during the LGM, most likely in the Caucasus.

Within the last 20,000 years or so, light skin has been favored by

natural selection in East Asia, Europe, and North America. At the same

time, Southern Africans tend to have lighter skin than their equatorial

counterparts. In general, people living in higher latitudes tend to have

lighter skin. The HERC2 variation for blue eyes first appears around 14,000 years ago in Italy and the Caucasus.

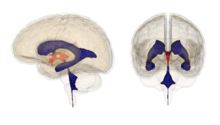

Larger average cranial capacity is correlated with living in cold regions.

Inuit adaptation to high-fat diet and cold climate has been traced to a mutation dated the Last Glacial Maximum (20,000 years ago). Average cranial capacity among modern male human populations varies in the range of 1,200 to 1,450 cm3. Larger cranial volumes are associated with cooler climatic regions, with the largest averages being found in populations of Siberia and the Arctic.

Humans living in Northern Asia and the Arctic have evolved the ability

to develop thick layers of fat on their faces to keep warm. Moreover,

the Inuit tend to have flat and broad faces, an adaptation that reduces

the likelihood of frostbites. Both Neanderthal

and Cro-Magnons had somewhat larger cranial volumes on average than

modern Europeans, suggesting the relaxation of selection pressures for

larger brain volume after the end of the LGM.

Australian Aboriginals living in the Central Desert,

where the temperature can drop below freezing at night, have evolved

the ability to reduce their core temperatures without shivering.

Early fossils of Homo sapiens suggest that members of this

species had vastly different brains 300,000 years ago compared to

today. In particular, they were elongated rather than globular in shape.

Only fossils from 35,000 years ago or less share the same basic brain

shape as that of current humans.

Human brains appear to be shrinking over the last twenty thousand

years. Modern human brains are about 10% smaller than those of the

Cro-Magnons, who lived in Europe twenty to thirty thousand years ago.

That is a difference comparable to a tennis ball. Scientists are not so

sure about the implications of this finding. On one hand, it could be

that humans are becoming less and less intelligent as their societies

become ever more complex, which makes it easier for them to survive. On

the other hand, shrinking brain sizes could be associated with lower

levels of aggression. In any case, evidence for the shrinking human brain can be observed in Africa, China, and Europe.

Even though it has long been thought that human culture—broadly

defined to be any learned behavior, including technology—has slowed

down, if not halted, human evolution, biologists working in the early

twenty-first century A.D. have come to the conclusion that instead,

human culture itself is a force of selection. Scans of the entire human

genome suggests large parts of it is under active selection within the

last 10,000 to 20,000 years or so, which is recent in evolutionary

terms. Although the details of such genes remain unclear (as of 2010),

they can still be categorized for likely functionality according to the

structures of the proteins for which they code. Many such genes are

linked to the immune system, the skin, metabolism, digestion, bone

development, hair growth, smell and taste, and brain function. Since the

culture of behaviorally modern humans undergoes rapid change, it is

possible that human culture has accelerated human evolution within the

last 50,000 years or so. While this possibility remains unproven,

mathematical models do suggest that gene-culture interactions can give

rise to especially speedy biological evolution. If this is true, then

humans are evolving to adapt to the selective pressures they created

themselves.

Holocene (12,000 years ago till present)

Neolithic or New Stone Age

All blue-eyed humans share a common ancestor.

Blue eyes are an adaptation for living in regions where the amounts

of light are limited because they allow more light to come in than brown

eyes. A research program by geneticist Hans Eiberg

and his team at the University of Copenhagen from the 1990s to 2000s

investigating the origins of blue eyes revealed that a mutation in the

gene OCA2

is responsible for this trait. According to them, all humans initially

had brown eyes and the OCA2 mutation took place between 6,000 and 10,000

years ago. It dilutes the production of melanin, responsible for the

pigmentation of human hair, eye, and skin color. The mutation does not

completely switch off melanin production, however, as that would leave

the individual with a condition known as albinism. Variations in eye

color from brown to green can be explained via the variation in the

amounts of melanin produced in the iris. While brown-eyed individuals

share a large area in their DNA controlling melanin production,

blue-eyed individuals have only a small region. By examining

mitochondrial DNA of people from multiple countries, Eiberg and his team

concluded blue-eyed individuals all share a common ancestor.

In 2018, an international team of researchers from Israel and the

United States announced their genetic analysis of 6,500-year-old

excavated human remains in Israel's Upper Galilee region revealed a

number of traits not found in the humans who had previously inhabited

the area, including blue eyes. They concluded that the region

experienced a significant demographic shift 6,000 years ago due to

migration from Anatolia and the Zagros mountains (in modern-day Turkey

and Iran) and that this change contributed to the development of the Chalcolithic culture in the region.

In 2006, population geneticist Jonathan Pritchard

and his colleagues studied the populations of Africa, East Asia, and

Europe and identified some 700 regions of the human genome as having

been shaped by natural selection between 15,000 and 5,000 years ago.

These genes affect the senses of smell and taste, skin color, digestion,

bone structure, and brain function. According to Spencer Wells,

director of the Genographic Project of the National Geographic Society,

such a study helps anthropologists explain in detail why peoples from

different parts of the globe can be so strikingly different in

appearance even though most of their DNA is identical.

The advent of agriculture has played a key role in the

evolutionary history of humanity. Early farming communities benefited

from new and comparatively stable sources of food, but were also exposed

to new and initially devastating diseases such as measles and smallpox.

Eventually, genetic resistance to such diseases evolved and humans

living today are descendants of those who survived the agricultural

revolution and reproduced. Diseases are one of the strongest forces of evolution acting on Homo sapiens.

As this species migrated throughout Africa and began colonizing new

lands outside the continent around 100,000 years ago, they came into

contact with and helped spread a variety of pathogens with deadly

consequences. In addition, the dawn of agriculture led to the rise of

major disease outbreaks. Malaria is the oldest known of human

contagions, traced to West Africa around 100,000 years ago, before

humans began migrating out of the continent. Malarial infections surged

around 10,000 years ago, raising the selective pressures upon the

affected populations, leading to the evolution of resistance.

A study by anthropologists John Hawks, Henry Harpending, Gregory Cochran, and colleagues suggests that human evolution has sped up significantly since the beginning of the Holocene, at an estimated pace of around 100 times faster than during the Paleolithic, primarily in the farming populations of Eurasia.

Thus, humans living in the twenty-first century are more different from

their ancestors of 5,000 years ago than their ancestors from that era

were to the Neanderthals who went extinct around 30,000 years ago.

They tied this effect to new selection pressures arising from new

diets, new modes of habitation, and immunological pressures related to

the domestication of animals.

For example, populations that cultivate rice, wheat, and other grains

have gained the ability to digest starch thanks to an enzyme called amylase, found in saliva. In addition, having a larger population means having more mutations, the raw material on which natural selection acts.

Hawks and colleagues scanned data from the International HapMap Project

of Africans, Asians, and Europeans for SNPs and found evidence of

evolution speeding up in 1800 genes, or 7% of the human genome.

They also discovered that human populations in Africa, Asia, and Europe

were evolving along divergent paths, becoming ever more different, and

that there was very little gene flow among them. Most of the new traits

are unique to their continent of origin.

Humans living in humid tropical areas show the least sign of

evolution, meaning ancestral humans were especially well-suited to these

places. Only when humans migrated out of them did natural selective

pressures arise. Moreover, African populations have the highest amounts

of genetic diversity; the further one moves from Africa, the more

homogeneous people become genetically. In fact, most of the variation in

the human genome is due not to natural selection but rather neutral

mutations and random shuffling of genes down the generations.

John Hawks reported evidence of recent evolution in the human

brain within the last 5,000 years or so. Measurements of the skull

suggests that the human brain has shrunk by about 150 cubic centimeters,

or roughly ten percent. This is likely due to the growing

specialization in modern societies centered around agriculture rather

than hunting and gathering.

More broadly, human brain sizes have been diminishing since at least

100,000 years ago, though the change was most significant within the

last 12,000 years. 100,000 years ago, the average brain size was about

1,500 cubic centimeters, compared to around 1,450 cubic centimeters

12,000 years ago and 1,350 today.

Examples for adaptations related to agriculture and animal domestication include East Asian types of ADH1B associated with rice domestication, and lactase persistence.

About ten thousand years ago, the rice-cultivating residents of

Southern China discovered that they could make alcoholic beverages by

fermentation. Drunkenness likely became a serious threat to survival and

a mutant gene for an enzyme that decomposes alcohol into something safe

and makes people's faces turn red, alcohol dehydrogenase, gradually spread throughout the rest of China.

Around 11,000 years ago, as agriculture was replacing hunting and

gathering in the Middle East, people invented ways to reduce the

concentrations of lactose in milk by fermenting

it to make yogurt and cheese. People lost the ability to digest lactose

as they matured and as such lost the ability to consume milk. Thousands

of years later, a genetic mutation enabled people living in Europe at

the time to continue producing lactase, an enzyme that digests lactose,

throughout their lives, allowing them to drink milk after weaning and

survive bad harvests.

These two key developments paved the way for communities of

farmers and herders to rapidly displace the hunter-gatherers who once

prevailed across Europe. Today, lactase persistence can be found in 90%

or more of the populations in Northwestern and Northern Central Europe,

and in pockets of Western and Southeastern Africa, Saudi Arabia, and

South Asia. It is not as common in Southern Europe (40%) because

Neolithic farmers had already settled there before the mutation existed.

On the other hand, it is rather rare in inland Southeast Asia and

Southern Africa. While all Europeans with lactase persistence share a

common ancestor for this ability, pockets of lactase persistence outside

Europe are likely due to separate mutations. The European mutation,

called the LP allele, is traced to modern-day Hungary, 7,500 years ago.

In the twenty-first century, about 35% of the human population is

capable of digesting lactose after the age of seven or eight.

Milk-drinking humans could produce offspring up to 19% more fertile than

those without the ability, putting the mutation among those under the

strongest selection known. As an example of gene-culture co-evolution,

communities with lactase persistence and dairy farming took over Europe

in several hundred generations, or thousands of years.

This raises a chicken-and-egg type of question: which came first, dairy

farming or lactase persistence? To answer this question, population

geneticists examined DNA samples extracted from skeletons found in

archeological sites in Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania dating

from between 3,800 and 6,000 years ago. They did not find any evidence

of the LP allele. Hence, Europeans began dairy farming before they

gained the ability to drink milk after early childhood.

A Finnish research team reported that the European mutation that

allows for lactase persistence is not found among the milk-drinking and

dairy-farming Africans, however. Sarah Tishkoff

and her students confirmed this by analyzing DNA samples from Tanzania,

Kenya, and Sudan, where lactase persistence evolved independently. The

uniformity of the mutations surrounding the lactase gene suggests that

lactase persistence spread rapidly throughout this part of Africa.

According to Tishkoff's data, this mutation first appeared between 3,000

and 7,000 years ago, and has been strongly favored by natural

selection, more strongly than even resistance to malaria, in fact. In

this part of the world, it provides some protection against drought and

enables people to drink milk without diarrhea, which causes dehydration.

Lactase persistence is a rare ability among mammals.

It is also a clear and simple example of convergent evolution in humans

because it involves a single gene. Other examples of convergent

evolution, such as the light skin of Europeans and East Asians or the

various means of resistance to malaria, are much more complicated.

Humans evolved light skin after migrating from Africa to Europe and East Asia.

The shift towards settled communities based on farming was a

significant cultural change, which in turn may have accelerated human

evolution. Agriculture brought about an abundance of cereals, enabling

women to wean their babies earlier and have more children over shorter

periods of time. Despite the vulnerability of densely populated

communities to diseases, this led to a population explosion and thus

more genetic variation, the raw material on which natural selection

acts. Diets in early agricultural communities were deficient in many

nutrients, including vitamin D. This could be one reason why natural

selection has favored fair skin among Europeans, as it increases UV

absorption and synthesis of vitamin D.

Paleoanthropologist Richard G. Klein of Stanford University told the New York Times

that while it was difficult to correlate a given genetic change with a

specific archeological period, it was possible to identify a number of

modifications as due to the rise of agriculture. Rice cultivation spread

across China between 7,000 and 6,000 years ago and reached Europe at

about the same time. Scientists have had trouble finding Chinese

skeletons before that period resembling that of a modern Chinese person

or European skeletons older than 10,000 years similar to that of a

modern European.

Among the list of genes Jonathan Pritchard and his team studied

were five that influenced complexion. Selected versions of the genes,

thought to have first emerged 6,600 years ago, were found only among

Europeans and were responsible for their pale skin. The consensus among

anthropologists is that when the first anatomically modern humans

arrived in Europe 45,000 years ago, they shared the dark skin of their

African ancestors but eventually acquired lighter skin as an adaptation

that helped them synthesize vitamin D using sunlight. This means that

either the Europeans acquired their light skin much more recently or

that this was a continuation of an earlier trend. Because East Asians

are also pale, nature achieved the same result either by selecting

different genes not detected by the test or by doing so to the same

genes but thousands of years earlier, making such changes invisible to

the test.

Non-human primates have no pigments in their skin because they

have fur. But when humans lost their fur—enabling them to sweat

efficiently—they needed dark skin to protect themselves against

ultraviolet radiation. Later research revealed that the so-called golden

gene, thus named because of the color it gives to zebrafish, is

ubiquitous among Europeans but rare among East Asians, suggesting there

was little gene flow between the two populations. Among East Asians, a

different gene, DCT, likely contributed to their fair skin.

Bronze Age to Medieval Era

Sickle cell anemia is an adaptation against malaria.

Resistance to malaria is a well-known example of recent human

evolution. This disease attacks humans early in life. Thus humans who

are resistant enjoy a higher chance of surviving and reproducing. While

humans have evolved multiple defenses against malaria, sickle cell anemia—a

condition in which red blood cells are deformed into sickle shapes,

thereby restricting blood flow—is perhaps the best known. Sickle cell

anemia makes it more difficult for the malarial parasite to infect red

blood cells. This mechanism of defense against malaria emerged

independently in Africa and in Pakistan and India. Within 4,000 years it

has spread to 10-15% of the populations of these places.

Another mutation that enabled humans to resist malaria that is strongly

favored by natural selection and has spread rapidly in Africa is the

inability of synthesize the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, or

G6PD.

A combination of poor sanitation and high population densities

proved ideal for the spread of contagious diseases which was deadly for

the residents of ancient cities. Evolutionary thinking would suggest

that people living in places with long-standing urbanization dating back

millennia would have evolved resistance to certain diseases, such as tuberculosis and leprosy.

Using DNA analysis and archeological findings, scientists from the

University College London and the Royal Holloway studied samples from 17

sites in Europe, Asia, and Africa. They learned that, indeed, long-term

exposure to pathogens has led to resistance spreading across urban

populations. Urbanization is therefore a selective force that has

influenced human evolution. The allele in question is named SLC11A1

1729+55del4. Scientists found that among the residents of places that

have been settled for thousands of years, such as Susa in Iran, this

allele is ubiquitous whereas in places with just a few centuries of

urbanization, such as Yakutsk in Siberia, only 70-80% of the population

have it.

Adaptations have also been found in modern populations living in extreme climatic conditions such as the Arctic, as well as immunological adaptations such as resistance against brain disease in populations practicing mortuary cannibalism, or the consumption of human corpses.

Inuit have the ability to thrive on the lipid-rich diets consisting of

Arctic mammals. Human populations living in regions of high attitudes,

such as the Tibetan Plateau, Ethiopia, and the Andes benefit from a

mutation that enhances the concentration of oxygen in their blood. This is achieved by having more capillaries, increasing their capacity for carrying oxygen. This mutation is believed to be around 3,000 years old.

Geneticist Ryosuke Kimura and his team at the Tokai University

School of Medicine discovered that an allele called EDAR, practically

absent among Europeans and Africans but common among East Asians, gives

rise to thicker hair, presumably as an adaptation to the cold. Kohichiro

Yoshihura and his team at Nagasaki University found that a variant of

the gene ABCC11 produces dry ear wax among East Asians. Africans and

Europeans by contrast share the older version of the gene, producing wet

ear wax. However, it is not known what evolutionary advantage, if any,

wet ear wax confers, so this variant was likely selected for some other

trait, such as making people sweat less. What scientists do know, however, is that dry ear wax is strongly favored by natural selection in East Asia.

The Sama-Bajau have evolved to become durable free divers.

A recent adaptation has been proposed for the Austronesian Sama-Bajau, also known as the Sea Gypsies or Sea Nomads, developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on free-diving over the past thousand years or so. As maritime hunter-gatherers, the ability to dive for long periods of times plays a crucial role in their survival. Due to the mammalian dive reflex,

the spleen contracts when the mammal dives and releases oxygen-carrying

red blood cells. Over time, individuals with larger spleens were more

likely to survive and thrive because free-diving can actually be quite

dangerous. By contrast, communities centered around farming show no

signs of evolving to have larger spleens. Because the Sama-Bajau show no

interest in abandoning this lifestyle, there is no reason to believe

further adaptation will not occur.

Advances in the biology of genomes have enabled geneticists to

investigate the course of human evolution within centuries or even

decades. Jonathan Pritchard and a postdoctoral fellow, Yair Field, found

a way to track changes in the frequency of an allele using huge genomic

data sets. They did this by counting the singletons, or changes of

single DNA bases, which are likely to be recent because they are rare

and have not spread throughout the population. Since alleles bring

neighboring DNA regions with them as they move around the genome, the

number of singletons can be used to roughly estimate how quickly the

allele has changed its frequency. This approach can unveil evolution

within the last 2,000 years or a hundred human generations. Armed with

this technique and data from the UK10K project, Pritchard and his team

found that alleles for lactase persistence, blond hair, and blue eyes

have spread rapidly among Britons within the last two millennia or so.

Britain's cloudy skies may have played a role in that the genes for fair

hair could also bring fair skin, reducing the chances of vitamin D

deficiency. Sexual selection could play a role, too, driven by fondness

of mates with blond hair and blue eyes. The technique also enabled them

to track the selection of polygenic traits—those affected by a multitude

of genes, rather than just one—such as height, infant head

circumferences, and female hip sizes (crucial for giving birth).

They found that natural selection has been favoring increased height

and larger head and female hip sizes among Britons. Moreover, lactase

persistence showed signs of active selection during the same period.

However, evidence for the selection of polygenic traits is weaker than

those affected only by one gene.

A 2012 paper studied the DNA sequence of around 6,500 Americans

of European and African descent and confirmed earlier work indicating

that the majority of changes to a single letter in the sequence (single

nucleotide variants) were accumulated within the last 5,000-10,000

years. Almost three quarters arose in the last 5,000 years or so. About

14% of the variants are potentially harmful, and among those, 86% were

5,000 years old or younger. The researchers also found that European

Americans had accumulated a much larger number of mutations than African

Americans. This is likely a consequence of their ancestors' migration

out of Africa, which resulted in a genetic bottleneck; there were few

mates available. Despite the subsequent exponential growth in

population, natural selection has not had enough time to eradicate the

harmful mutations. While humans today carry far more mutations than

their ancestors did 5,000 years ago, they are not necessarily more

vulnerable to illnesses because these might be caused by multiple

mutations. It does, however, confirm earlier research suggesting that

common diseases are not caused by common gene variants.

In any case, the fact that the human gene pool has accumulated so many

mutations over such a short period of time—in evolutionary terms—and

that the human population has exploded in that time mean that humanity

is more evolvable than ever before. Natural selection might eventually

catch up with the variations in the gene pool, as theoretical models

suggest that evolutionary pressures increase as a function of population

size.

Industrial Revolution to present

Even

though modern healthcare reduces infant mortality rates and extends

life expectancy, natural selection continues to act on humans.

Geneticist Steve Jones told the BBC that during the sixteenth

century, only a third of English babies survived till the age of 21,

compared to 99% in the twenty-first century. Medical advances,

especially those made in the twentieth century, made this change

possible. Yet while people from the developed world today are living

longer and healthier lives, many are choosing to have just a few or no

children at all, meaning evolutionary forces continue to act on the

human gene pool, just in a different way.

While modern medicine appears to shield humanity from the

pressures of natural selection, it does not prevent other evolutionary

processes from taking place. According to neutral selection theory,

natural selection affects only 8% of the human genome, meaning mutations

in the remaining parts of the genome can change their frequency by pure

chance. If natural selective pressures are reduced, then traits that

are normally purged are not removed as quickly, which could increase

their frequency and speed up evolution. There is evidence that the rate

of human mutation is rising. For humans, the largest source of heritable

mutations is sperm; a man accumulates more and more mutations in his

sperm as he ages. Hence, men delaying reproduction can affect human

evolution. The accumulation of so many mutations in a short period of

time could pose genetic problems for future human generations.

A 2012 study led by Augustin Kong suggests that the number of de novo

(or new) mutations increases by about two per year of delayed

reproduction by the father and that the total number of paternal

mutations doubles every 16.5 years.

Dependence on modern medicine itself is another evolutionary time

bomb. For a long time, it has reduced the fatality of genetic defects

and contagious diseases, allowing more and more humans to survive and

reproduce, but it has also enabled maladaptive traits that would

otherwise be culled to accumulate in the gene pool. This is not a

problem as long as access to modern healthcare is maintained. But

natural selective pressures will mount considerably if that is taken

away.

Nevertheless, dependence on medicine rather than genetic adaptations

will likely be the driving force behind humanity's fight against

diseases for the foreseeable future. Moreover, while the introduction of

antibiotics initially reduced the mortality rates due to infectious

diseases by significant amounts, abuse has led to the rise of resistant

strains of bacteria, making many illnesses major causes of death once

again.

Human jaws and teeth have been shrinking in proportion with the

decrease in body size in the last 30,000 years as a result of new diets

and technology. There are many individuals today who do not have enough

space in their mouths for their third molars (or wisdom teeth)

due to reduced jaw sizes. In the twentieth century, the trend toward

smaller teeth appeared to have been slightly reversed due to the

introduction of fluoride, which thickens dental enamel, thereby

enlarging the teeth.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the average height of

Dutch soldiers was 165 cm, well below European and American averages.

However, 150 years later, the Dutch gained an average of 20 cm while the

Americans only 6 cm. This is due to the fact that tall Dutchmen on

average had more children than those who were short, as Dutchwomen found

them more attractive, and that while tall Dutchwomen on average had

fewer children than those of medium heights, they did have more children

than those who were short. Things like good nutrition and good

healthcare did not play as important a role as biological evolution.

By contrast, in some other countries such as the United States, for

example, men of average height and short women tended to have more

children.

Recent research suggests that menopause is evolving to occur

later. Other reported trends appear to include lengthening of the human

reproductive period and reduction in cholesterol levels, blood glucose

and blood pressure in some populations.

Population geneticist Emmanuel Milot and his team studied recent

human evolution in an isolated Canadian island using 140 years of church

records. They found that selection favored younger age at first birth

among women. In particular, the average age at first birth of women from Coudres Island (Île aux Coudres),

80 km northeast of Québec City, decreased by four years between 1800

and 1930. Women who started having children sooner generally ended up

with more children in total who survive till adulthood. In other words,

for these French-Canadian women, reproductive success was associated

with lower age at first childbirth. Maternal age at first birth is a

highly heritable trait.

Human evolution continues during the modern era, including among

industrialized nations. Things like access to contraception and the

freedom from predators do not stop natural selection.

Among developed countries, where life expectancy is high and infant

mortality rates are low, selective pressures are the strongest on traits

that influence the number of children a human has. It is speculated

that alleles influencing sexual behavior would be subject to strong

selection, though the details of how genes can affect said behavior

remain unclear.

Historically, as a by-product of the ability to walk upright,

humans evolved to have narrower hips and birth canals and to have larger

heads. Compared to other close relatives such as chimpanzees,

childbirth is a highly challenging and potentially fatal experience for

humans. Thus began an evolutionary tug-of-war. For babies, having larger

heads proved beneficial as long as their mothers' hips were wide

enough. If not, both mother and child typically died. This is an example

of balancing selection,

or the removal of extreme traits. In this case, heads that were too

large or small were selected against. This evolutionary tug-of-war

attained an equilibrium, making these traits remain more or less

constant over time while allowing for genetic variation to flourish,

thus paving the way for rapid evolution should selective forces shift

their direction.

All this changed in the twentieth century as Cesarean sections (or C-sections) became safer and more common in some parts of the world.

Larger head sizes continue to be favored while selective pressures

against smaller hip sizes have diminished. Projecting forward, this

means that human heads would continue to grow while hip sizes would not.

As a result of increasing fetopelvic disproportion, C-sections would

become more and more common in a positive feedback loop, though not

necessarily to the extent that natural childbirth would become obsolete.

Paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner of the Smithsonian Institute

noted that cultural factors could play a role in the widely different

rates of C-sections across the developed and developing worlds. Daghni

Rajasingam of the Royal College of Obstetricians observed that the

increasing rates of diabetes and obesity among women of reproductive age

also boost the demand for C-sections.

Biologist Philipp Mitteroecker from the University of Vienna and his

team estimated that about six percent of all births worldwide were

obstructed and required medical intervention. In the United Kingdom, one

quarter of all births involved the C-section while in the United

States, the number was one in three. Mitteroecker and colleagues

discovered that the rate of C-sections has gone up 10% to 20% since the

mid-twentieth century. They argued that because the availability of safe

Cesarean sections significantly reduced maternal and infant mortality

rates in the developed world, they have induced an evolutionary change.

However, "It's not easy to foresee what this will mean for the future of

humans and birth," Mitteroecker told The Independent. This is

because the increase in baby sizes is limited by the mother's metabolic

capacity and modern medicine, which makes it more likely that neonates

who are born prematurely or are underweight to survive.

Westerners are evolving to have lower blood pressures because their modern diets contain high amounts of salt (

NaCl), which raises blood pressure.

Researchers participating in the Framingham Heart Study,

which began in 1948 and was intended to investigate the cause of heart

disease among women and their descendants in Framingham, Massachusetts,

found evidence for selective pressures against high blood pressure

due to the modern Western diet, which contains high amounts of salt,

known for raising blood pressure. They also found evidence for selection

against hypercholesterolemnia, or high levels of cholesterol in the blood.

Evolutionary geneticist Stephen Stearns and his colleagues reported

signs that women were gradually becoming shorter and heavier. Stearns

argued that human culture and changes humans have made on their natural

environments are driving human evolution rather than putting the process

to a halt. The data indicates that the women were not eating more; rather, the ones who were heavier tended to have more children.

Stearns and his team also discovered that the subjects of the study

tended to reach menopause later; they estimated that if the environment

remains the same, the average age at menopause will increase by about a

year in 200 years, or about ten generations. All these traits have

medium to high heritability. Given the starting date of the study, the spread of these adaptations can be observed in just a few generations.

By analyzing genomic data of 60,000 individuals of Caucasian descent from Kaiser Permanente in Northern California, and 150,000 people the UK Biobank,

evolutionary geneticist Joseph Pickrell and evolutionary biologist

Molly Przeworski were able to identify signs of biological evolution

among living human generations. For the purposes of studying evolution,

one lifetime is the shortest possible time scale. An allele associated

with difficulty withdrawing from tobacco smoking dropped in frequency

among the British but not among the Northern Californians. This suggests

that heavy smokers—who were common in Britain during the 1950s but not

in Northern California—were selected against. A set of alleles linked to

later menarche was more common among women who lived for longer. An

allele called ApoE4, linked to Alzheimer's disease, fell in frequency as carriers tended to not live for very long.

In fact, these were the only traits that reduced life expectancy

Pickrell and Przeworski found, which suggests that other harmful traits

probably have already been eradicated. Only among older people are the

effects of Alzheimer's disease and smoking visible. Moreover, smoking is

a relatively recent trend. It is not entirely clear why such traits

bring evolutionary disadvantages, however, since older people have

already had children. Scientists proposed that either they also bring

about harmful effects in youth or that they reduce an individual's inclusive fitness,

or the tendency of organisms that share the same genes to help each

other. Thus, mutations that make it difficult for grandparents to help

raise their grandchildren are unlikely to propagate throughout the

population.

Pickrell and Przeworski also investigated 42 traits determined by

multiple alleles rather than just one, such as the timing of puberty.

They found that later puberty and older age of first birth were

correlated with higher life expectancy.

Larger sample sizes allow for the study of rarer mutations. Pickrell and Przeworski told The Atlantic

that a sample of half a million individuals would enable them to study

mutations that occur among only 2% of the population, which would

provide finer details of recent human evolution.

While studies of short time scales such as these are vulnerable to

random statistical fluctuations, they can improve understanding of the

factors that affect survival and reproduction among contemporary human

populations.

Evolutionary geneticist Jaleal Sanjak and his team analyzed

genetic and medical information from more than 200,000 women over the

age of 45 and 150,000 men over the age of 50—people who have passed

their reproductive years—from the UK Biobank and identified 13 traits

among women and ten among men that were linked to having children at a

younger age, having a higher body-mass index, fewer years of education, and lower levels of fluid intelligence,

or the capacity for logical reasoning and problem solving. Sanjak

noted, however, that it was not known whether having children actually

made women heavier or being heavier made it easier to reproduce. Because

taller men and shorter women tended to have more children and because

the genes associated with height affect men and women equally, the

average height of the population will likely remain the same. Among

women who had children later, those with higher levels of education had

more children.

Evolutionary biologist Hakhamanesh Mostafavi led a 2017 study

that analyzed data of 215,000 individuals from just a few generations

the United Kingdom and the United States and found a number of genetic

changes that affect longevity. The ApoE allele linked to Alzheimer's disease was rare among women aged 70 and over while the frequency of the CHRNA3

gene associated with smoking addiction among men fell among middle-aged

men and up. Because this is not itself evidence of evolution, since

natural selection only cares about successful reproduction not

longevity, scientists have proposed a number of explanations. Men who

live longer tend to have more children. Men and women who survive till

old age can help take care of both their children and grandchildren, in

benefits their descendants down the generations. This explanation is

known as the grandmother hypothesis.

It is also possible that Alzheimer's disease and smoking addiction are

also harmful earlier in life, but the effects are more subtle and larger

sample sizes are required in order to study them. Mostafavi and his

team also found that mutations causing health problems such as asthma,

having a high body-mass index and high cholesterol levels were more

common among those with shorter lifespans while mutations those leading

to delayed puberty and reproduction were more common among long living

individuals. According to geneticist Jonathan Pritchard, while the link

between fertility and longevity was identified in previous studies,

those did not entirely rule out the effects of educational and financial

status—people who rank high in both tend to have children later in

life; this seems to suggest the existence of an evolutionary trade-off

between longevity and fertility.

In South Africa, where large numbers of people are infected with

HIV, some have genes that help them combat this virus, making it more

likely that they would survive and pass this trait onto their children.

If the virus persists, humans living in this part of the world could

become resistant to it in as little as hundreds of years. However,

because HIV evolves more quickly than humans, it will more likely be

dealt with technologically rather than genetically.

The Amish have a mutation that extends their life expectancy and reduces their susceptibility to diabetes.

A 2017 study by researchers from Northwestern University unveiled a mutation among the Old Order Amish

living in Berne, Indiana, that suppressed their chances of having

diabetes and extends their life expectancy by about ten years on

average. That mutation occurred in the gene called Serpine1, which codes

for the production of the protein PAI-1

(plasminogen activator inhibitor), which regulates blood clotting and

plays a role in the aging process. About 24% of the people sampled

carried this mutation and had a life expectancy of 85, higher than the

community average of 75. Researchers also found the telomeres—non-functional

ends of human chromosomes—of those with the mutation to be longer than

those without. Because telomeres shorten as the person ages, they

determine the person's life expectancy. Those with longer telomeres tend

to live longer. At present, the Amish live in 22 U.S. states plus the

Canadian province of Ontario. They live simple lifestyles that date back

centuries and generally insulate themselves from modern North American

society. They are mostly indifferent towards modern medicine, but

scientists do have a healthy relationship with the Amish community in

Berne. Their detailed genealogical records make them ideal subjects for

research.

Multidisciplinary research suggests that ongoing evolution could

help explain the rise of certain medical conditions such as autism and autoimmune disorders.

Autism and schizophrenia may be due to genes inherited from the mother

and the father which are over-expressed and which fight a tug-of-war in

the child's body. Allergies, asthma,

and autoimmune disorders appear linked to higher standards of

sanitation, which prevent the immune systems of modern humans from being

exposed to various parasites and pathogens the way their ancestors'

were, making them hypersensitive and more likely to overreact. The human

body is not built from a professionally engineered blue print but a

system shaped over long periods of time by evolution with all kinds of

trade-offs and imperfections. Understanding the evolution of the human

body can help medical doctors better understand and treat various

disorders. Research in evolutionary medicine

suggests that diseases are prevalent because natural selection favors

reproduction over health and longevity. In addition, biological

evolution is slower than cultural evolution and humans evolve more

slowly than pathogens.

Whereas in the ancestral past, humans lived in geographically isolated communities where inbreeding was rather common,

modern transportation technologies have made it much easier for people

to travel great distances and facilitated further genetic mixing, giving

rise to additional variations in the human gene pool. It also enables the spread of diseases worldwide, which can have an effect on human evolution. Besides the selection and flow of genes and alleles, another mechanism of biological evolution is epigenetics,

or changes not to the DNA sequence itself, but rather the way it is

expressed. Scientists already know that chronic illnesses and stress are

epigenetic mechanisms