The perennial philosophy (Latin: philosophia perennis), also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a perspective in philosophy and spirituality that views all of the world's religious traditions as sharing a single, metaphysical truth or origin from which all esoteric and exoteric knowledge and doctrine has grown.

Perennialism has its roots in the Renaissance interest in neo-Platonism and its idea of the One, from which all existence emanates. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) sought to integrate Hermeticism with Greek and Jewish-Christian thought, discerning a prisca theologia which could be found in all ages. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94) suggested that truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions. He proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle, and saw aspects of the prisca theologia in Averroes (Ibn Rushd), the Quran, the Kabbalah and other sources. Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) coined the term philosophia perennis.

A more popular interpretation argues for universalism, the idea that all religions, underneath seeming differences, point to the same Truth. In the early 19th century the Transcendentalists propagated the idea of a metaphysical Truth and universalism, which inspired the Unitarians, who proselytized among Indian elites. Towards the end of the 19th century, the Theosophical Society further popularized universalism, not only in the western world, but also in western colonies. In the 20th century universalism was further popularized through the Advaita Vedanta inspired Traditionalist School, which argued for a metaphysical, single origin of the orthodox religions, and by Aldous Huxley and his book The Perennial Philosophy, which was inspired by neo-Vedanta and the Traditionalist School.

Definition

Renaissance

The idea of a perennial philosophy originated with a number of Renaissance theologians who took inspiration from neo-Platonism and from the theory of Forms. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) argued that there is an underlying unity to the world, the soul or love, which has a counterpart in the realm of ideas. According to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), a student of Ficino, truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions. According to Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) there is "one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples."

Traditionalist School

The contemporary, scholarly oriented Traditionalist School continues this metaphysical orientation. According to the Traditionalist School, the perennial philosophy is "absolute Truth and infinite Presence". Absolute Truth is "the perennial wisdom (sophia perennis) that stands as the transcendent source of all the intrinsically orthodox religions of humankind." Infinite Presence is "the perennial religion (religio perennis) that lives within the heart of all intrinsically orthodox religions." The Traditionalist School discerns a transcendent and an immanent dimension, namely the discernment of the Real or Absolute, c.q. that which is permanent; and the intentional "mystical concentration on the Real".

According to Soares de Azevedo, the perennialist philosophy states that the universal truth is the same within each of the world's orthodox religious traditions, and is the foundation of their religious knowledge and doctrine. Each world religion is an interpretation of this universal truth, adapted to cater for the psychological, intellectual, and social needs of a given culture of a given period of history. This perennial truth has been rediscovered in each epoch by mystics of all kinds who have revived already existing religions, when they had fallen into empty platitudes and hollow ceremonialism.

Shipley further notes that the Traditionalist School is oriented on orthodox traditions, and rejects modern syncretism and universalism, which creates new religions from older religions and compromise the standing traditions.

Aldous Huxley and mystical universalism

One such universalist was Aldous Huxley, who propagated a universalist interpretation of the world religions, inspired by Vivekananda's neo-Vedanta and his own use of psychedelic drugs. According to Huxley, who popularized the idea of a perennial philosophy with a larger audience,

The Perennial Philosophy is expressed most succinctly in the Sanskrit formula, tat tvam asi ('That thou art'); the Atman, or immanent eternal Self, is one with Brahman, the Absolute Principle of all existence; and the last end of every human being, is to discover the fact for himself, to find out who he really is.

In Huxley's 1944 essay in Vedanta and the West, he describes "The Minimum Working Hypothesis", the basic outline of the perennial philosophy found in all the mystic branches of the religions of the world:

That there is a Godhead or Ground, which is the unmanifested principle of all manifestation.

That the Ground is transcendent and immanent.

That it is possible for human beings to love, know and, from virtually, to become actually identified with the Ground.

That to achieve this unitive knowledge, to realize this supreme identity, is the final end and purpose of human existence.

That there is a Law or Dharma, which must be obeyed, a Tao or Way, which must be followed, if men are to achieve their final end.

Origins

The perennial philosophy originates from a blending of neo-Platonism and Christianity. Neo-Platonism itself has diverse origins in the syncretic culture of the Hellenistic period, and was an influential philosophy throughout the Middle Ages.

Classical world

Hellenistic period: religious syncretism

During the Hellenistic period, Alexander the Great's campaigns brought about exchange of cultural ideas on its path throughout most of the known world of his era. The Greek Eleusinian Mysteries and Dionysian Mysteries mixed with such influences as the Cult of Isis, Mithraism and Hinduism, along with some Persian influences. Such cross-cultural exchange was not new to the Greeks; the Egyptian god Osiris and the Greek god Dionysus had been equated as Osiris-Dionysus by the historian Herodotus as early as the 5th century BC (see Interpretatio graeca).

Roman world: Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (c.25 BCE – c.50 CE) attempted to reconcile Greek Rationalism with the Torah, which helped pave the way for Christianity with Neo-Platonism, and the adoption of the Old Testament with Christianity, as opposed to Gnostic roots of Christianity. Philo translated Judaism into terms of Stoic, Platonic and Neopythagorean elements, and held that God is "supra rational" and can be reached only through "ecstasy." He also held that the oracles of God supply the material of moral and religious knowledge.

Neo-Platonism

Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century CE and persisted until shortly after the closing of the Platonic Academy in Athens in AD 529 by Justinian I. Neoplatonists were heavily influenced by Plato, but also by the Platonic tradition that thrived during the six centuries which separated the first of the Neoplatonists from Plato. The work of Neoplatonic philosophy involved describing the derivation of the whole of reality from a single principle, "the One." It was founded by Plotinus, and has been very influential throughout history. In the Middle Ages, Neoplatonic ideas were integrated into the philosophical and theological works of many of the most important medieval Islamic, Christian, and Jewish thinkers.

Renaissance

Ficino and Pico della Mirandola

Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) believed that Hermes Trismegistos, the supposed author of the Corpus Hermeticum, was a contemporary of Mozes and the teacher of Pythagoras, and the source of both Greek and Jewish-Christian thought. He argued that there is an underlying unity to the world, the soul or love, which has a counterpart in the realm of ideas. Platonic Philosophy and Christian theology both embody this truth. Ficino was influenced by a variety of philosophers including Aristotelian Scholasticism and various pseudonymous and mystical writings. Ficino saw his thought as part of a long development of philosophical truth, of ancient pre-Platonic philosophers (including Zoroaster, Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Aglaophemus and Pythagoras) who reached their peak in Plato. The Prisca theologia, or venerable and ancient theology, which embodied the truth and could be found in all ages, was a vitally important idea for Ficino.

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94), a student of Ficino, went further than his teacher by suggesting that truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions. This proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle, and saw aspects of the Prisca theologia in Averroes, the Koran, the Cabala among other sources. After the deaths of Pico and Ficino this line of thought expanded, and included Symphorien Champier, and Francesco Giorgio.

Steuco

De perenni philosophia libri X

The term perenni philosophia was first used by Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) who used it to title a treatise, De perenni philosophia libri X, published in 1540. De perenni philosophia was the most sustained attempt at philosophical synthesis and harmony. Steuco represents the liberal wing of 16th-century Biblical scholarship and theology, although he rejected Luther and Calvin. De perenni philosophia, is a complex work which only contains the term philosophia perennis twice. It states that there is "one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples." This single knowledge (or sapientia) is the key element in his philosophy. In that he emphasises continuity over progress, Steuco's idea of philosophy is not one conventionally associated with the Renaissance. Indeed, he tends to believe that the truth is lost over time and is only preserved in the prisci theologica. Steuco preferred Plato to Aristotle and saw greater congruence between the former and Christianity than the latter philosopher. He held that philosophy works in harmony with religion and should lead to knowledge of God, and that truth flows from a single source, more ancient than the Greeks. Steuco was strongly influenced by Iamblichus's statement that knowledge of God is innate in all, and also gave great importance to Hermes Trismegistus.

Influence

Steuco's perennial philosophy was highly regarded by some scholars for the two centuries after its publication, then largely forgotten until it was rediscovered by Otto Willmann in the late part of the 19th century. Overall, De perenni philosophia wasn't particularly influential, and largely confined to those with a similar orientation to himself. The work was not put on the Index of works banned by the Roman Catholic Church, although his Cosmopoeia which expressed similar ideas was. Religious criticisms tended to the conservative view that held Christian teachings should be understood as unique, rather than seeing them as perfect expressions of truths that are found everywhere. More generally, this philosophical syncretism was set out at the expense of some of the doctrines included within it, and it is possible that Steuco's critical faculties were not up to the task he had set himself. Further, placing so much confidence in the prisca theologia, turned out to be a shortcoming as many of the texts used in this school of thought later turned out to be bogus. In the following two centuries the most favourable responses were largely Protestant and often in England.

Gottfried Leibniz later picked up on Steuco's term. The German philosopher stands in the tradition of this concordistic philosophy; his philosophy of harmony especially had affinity with Steuco's ideas. Leibniz knew about Steuco's work by 1687, but thought that De la vérité de la religion chrétienne by Huguenot philosopher Phillippe du Plessis-Mornay expressed the same truth better. Steuco's influence can be found throughout Leibniz's works, but the German was the first philosopher to refer to the perennial philosophy without mentioning the Italian.

Popularisation

Transcendentalism and Unitarian Universalism

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) was a pioneer of the idea of spirituality as a distinct field. He was one of the major figures in Transcendentalism, which was rooted in English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume. The Transcendentalists emphasised an intuitive, experiential approach of religion. Following Schleiermacher, an individual's intuition of truth was taken as the criterion for truth. In the late 18th and early 19th century, the first translations of Hindu texts appeared, which were also read by the Transcendentalists, and influenced their thinking. They also endorsed universalist and Unitarian ideas, leading in the 20th Century to Unitarian Universalism. Universalism holds the idea that there must be truth in other religions as well, since a loving God would redeem all living beings, not just Christians.

Theosophical Society

By the end of the 19th century, the idea of a perennial philosophy was popularized by leaders of the Theosophical Society such as H. P. Blavatsky and Annie Besant, under the name of "Wisdom-Religion" or "Ancient Wisdom". The Theosophical Society took an active interest in Asian religions, subsequently not only bringing those religions under the attention of a western audience but also influencing Hinduism and Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Japan.

Neo-Vedanta

Many perennialist thinkers (including Armstrong, Huston Smith and Joseph Campbell) are influenced by Hindu reformer Ram Mohan Roy and Hindu mystics Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, who themselves have taken over western notions of universalism. They regarded Hinduism to be a token of this perennial philosophy. This notion has influenced thinkers who have proposed versions of the perennial philosophy in the 20th century.

The unity of all religions was a central impulse among Hindu reformers in the 19th century, who in turn influenced many 20th-century perennial philosophy-type thinkers. Key figures in this reforming movement included two Bengali Brahmins. Ram Mohan Roy, a philosopher and the founder of the modernising Brahmo Samaj religious organisation, reasoned that the divine was beyond description and thus that no religion could claim a monopoly in their understanding of it.

The mystic Ramakrishna's spiritual ecstasies included experiencing the sameness of Christ, Mohammed and his own Hindu deity. Ramakrishna's most famous disciple, Swami Vivekananda, travelled to the United States in the 1890s where he formed the Vedanta Society.

Roy, Ramakrishna and Vivekananda were all influenced by the Hindu school of Advaita Vedanta, which they saw as the exemplification of a Universalist Hindu religiosity.

Traditionalist School

The Traditionalist School is a group of 20th and 21st century thinkers concerned with what they consider to be the demise of traditional forms of knowledge, both aesthetic and spiritual, within Western society. The principal thinkers in this tradition are René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy and Frithjof Schuon. Other important thinkers in this tradition include Titus Burckhardt, Martin Lings, Jean-Louis Michon, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith, Hossein Nasr, Jean Borella, Elémire Zolla and Julius Evola. According to the Traditionalist School, orthodox religions are based on a singular metaphysical origin. According to the Traditionalist School, the "philosophia perennis" designates a worldview that is opposed to the scientism of modern secular societies and which promotes the rediscovery of the wisdom traditions of the pre-secular developed world. This view is exemplified by Rene Guenon in The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, one of the founding works of the traditionalist school.

According to Frithjof Schuon:

It has been said more than once that total Truth is inscribed in an eternal script in the very substance of our spirit; what the different Revelations do is to "crystallize" and "actualize", in different degrees according to the case, a nucleus of certitudes which not only abides forever in the divine Omniscience, but also sleeps by refraction in the "naturally supernatural" kernel of the individual, as well as in that of each ethnic or historical collectivity or of the human species as a whole.

Aldous Huxley

The term was popularized in more recent times by Aldous Huxley, who was profoundly influenced by Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta and Universalism. In his 1945 book The Perennial Philosophy he defined the perennial philosophy as:

... the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical to, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being; the thing is immemorial and universal. Rudiments of the perennial philosophy may be found among the traditional lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.

In contrast to the Traditionalist school, Huxley emphasized mystical experience over metaphysics:

The Buddha declined to make any statement in regard to the ultimate divine Reality. All he would talk about was Nirvana, which is the name of the experience that comes to the totally selfless and one-pointed [...] Maintaining, in this matter, the attitude of a strict operationalist, the Buddha would speak only of the spiritual experience, not of the metaphysical entity presumed by the theologians of other religions, as also of later Buddhism, to be the object and (since in contemplation the knower, the known and the knowledge are all one) at the same time the subject and substance of that experience.

According to Aldous Huxley, in order to apprehend the divine reality, one must choose to fulfill certain conditions: "making themselves loving, pure in heart and poor in spirit." Huxley argues that very few people can achieve this state. Those who have fulfilled these conditions, grasped the universal truth and interpreted it have generally been given the name of saint, prophet, sage or enlightened one. Huxley argues that those who have, "modified their merely human mode of being," and have thus been able to comprehend "more than merely human kind and amount of knowledge" have also achieved this enlightened state.

New Age

The idea of a perennial philosophy is central to the New Age Movement. The New Age movement is a Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational psychology, holistic health, parapsychology, consciousness research and quantum physics". The term New Age refers to the coming astrological Age of Aquarius.

The New Age aims to create "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas" that is inclusive and pluralistic. It holds to "a holistic worldview", emphasising that the Mind, Body and Spirit are interrelated and that there is a form of monism and unity throughout the universe. It attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality" and embraces a number of forms of mainstream science as well as other forms of science that are considered fringe.

Academic discussions

Mystical experience

The idea of a perennial philosophy, sometimes called perennialism, is a key area of debate in the academic discussion of mystical experience. Huston Smith notes that the Traditionalist School's vision of a perennial philosophy is not based on mystical experiences, but on metaphysical intuitions. The discussion of mystical experience has shifted the emphasis in the perennial philosophy from these metaphysical intuitions to religious experience and the notion of nonduality or altered state of consciousness.

William James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his The Varieties of Religious Experience. It has also influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge. Writers such as W.T. Stace, Huston Smith, and Robert Forman argue that there are core similarities to mystical experience across religions, cultures and eras. For Stace the universality of this core experience is a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for one to be able to trust the cognitive content of any religious experience.

Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" further back to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique. It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential.

Critics point out that the emphasis on "experience" favours the atomic individual, instead of the community. It also fails to distinguish between episodic experience, and mysticism as a process, embedded in a total religious matrix of liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals and practices. Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:

The privatisation of mysticism - that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences - serves to exclude it from political issues such as social justice. Mysticism thus comes to be seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than serving to transform the world, reconcile the individual to the status quo by alleviating anxiety and stress.

Religious pluralism

Religious pluralism holds that various world religions are limited by their distinctive historical and cultural contexts and thus there is no single, true religion. There are only many equally valid religions. Each religion is a direct result of humanity's attempt to grasp and understand the incomprehensible divine reality. Therefore, each religion has an authentic but ultimately inadequate perception of divine reality, producing a partial understanding of the universal truth, which requires syncretism to achieve a complete understanding as well as a path towards salvation or spiritual enlightenment.

Although perennial philosophy also holds that there is no single true religion, it differs when discussing divine reality. Perennial philosophy states that the divine reality is what allows the universal truth to be understood. Each religion provides its own interpretation of the universal truth, based on its historical and cultural context. Therefore, each religion provides everything required to observe the divine reality and achieve a state in which one will be able to confirm the universal truth and achieve salvation or spiritual enlightenment.

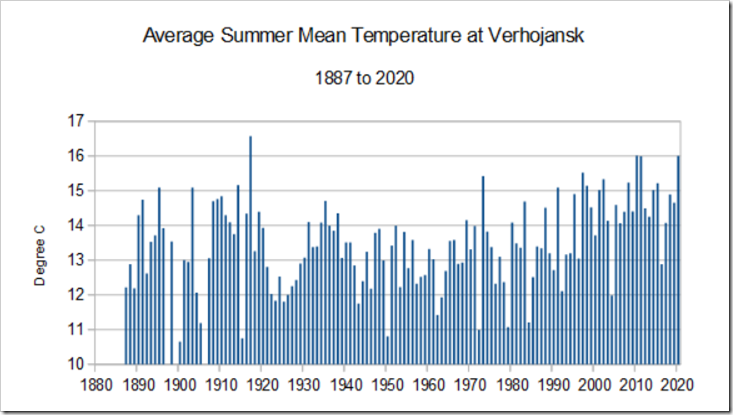

Meanwhile, over in the US, 1917 was the coldest year on record, as was the Spring of that year.

Forgive me if I’m wrong, but I thought the 38 degree reading was very questionable and unlikely to be confirmed? What have I missed?

Don’t let the BBC know that it wasn’t a record.

‘Normal’ for Jan is -41/-48C, -55/-56C today, lows of -62C forecast in next few days.

Just the weather pendulum!

NTZ on Arctic ‘warming’. Says pretty much what we’ve all pointed out before.

https://notrickszone.com/2021/01/13/arctic-temps-show-little-change-over-past-90-years-in-sync-with-oceanic-surface-temperature-cycles/

High temperatures are quite common in the Eurasian Arctic summer. Temperatures over 34 Celsius have been recorded at Tiksi (latitude 71 degrees north) on the edge of the Laptev Sea, and over 36 Celsius at Khatanga (similar latitude) at the eastern base of the Taymyr Peninsula. It is worth noting that the Verkhoyansk record occured on 20 June with 24 hour insolation, and also that Verkhoyansk is noted for its extremes, both hot and cold enhanced by its situation.

BBC inviting comment in an on line survey

https://www.bbc.co.uk/send/u61149175

enjoy…. if you want to pass comment on wall to wall climate and covid scaremongering

Done!

In their ‘submission received’ email, they say: “We’ll keep it for up to 270 days – and if we don’t use it we’ll then delete it and any other information you sent us.

We really appreciate your help to understand what you think and feel about the BBC.”

I have a feeling they won’t be keeping mine!

I bet they don’t get the chance to change/alter/massage/dicredit that record! But I bet they try.

It wasn’t even “one day”, it was simply one moment. The “day” may not have been the hottest – it might have been colder to start with and then got colder quickly after the high temperature. Using Tmax as the temperature for a period is simply wrong.

O/T Effect of lockdown on air pollution in UK.

Some may remember the discussions we had on this topic regarding the situation in the UK, puzzled at the claims of miraculously cleansed air – which did not seem to be very obvious in the actual monitoring station data.

Other research has already agreed that PMs did not decrease significantly, increased even, in the period after traffic almost disappeared overnight from UK roads.

This new paper also suggests that in London, after the traffic vanished, ozone increased by 26%, and NO2 decreased by only 10%, with -2% and -8% respectively due to lockdown.

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2021/01/13/first-lockdowns-effect-on-air-pollution-was-overstated-our-study-reveals/

London has a lot of highly polluting buses and taxis and as I thought with the Marylebone Road data, the pollution was mostly related to those and not private cars – they returned at different times/rates, the pollution only really increased after the bus/taxi movements increased again. That small -8% in NO2 is likely mostly not due to cars.

It is now obvious that a total ban on private ICE cars in London (and elsewhere) will not make any significant different to air quality and private motorists have been unfairly and politically targeted. Air quality in the UK is already extremely good, with massive improvements in recent decades, and ICE car emissions standards are extremely high.

History suggests the globe will continue to warm on and off until the next ice age starts, so expect more cherrypicking of short-term weather events as evidence of…well, nothing really.

In 1917 the Thames froze in London, reported the Dailey telegraph. People had problems acquiring coal. There was a rumpus about 45 cwt of the stuff being sent to a museum while others were in fuel poverty.

Coal ships used to pull up on the beach near me, after a storm you can find lost coal washed up or uncovered, some chunks are the size of a football.

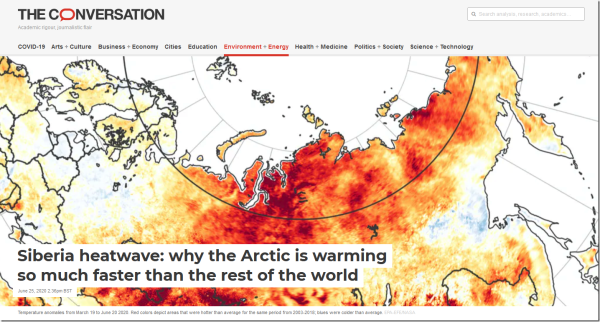

Here is my work on the Verkhoyansk thing for what it’s worth.

https://tambonthongchai.com/2020/07/19/agw-heat-wave-in-siberia/

My main point there is that time and geography constrained temperature events do not have a global warming interpretation.

For that one must look at the global warming data

These data are over long time spans and the temperature data are for large geographical regions that are significant portions of the globe.

https://tambonthongchai.com/2021/01/11/global-warming-dec2020/