From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

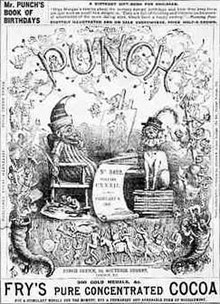

1867 edition of Punch, a ground-breaking British magazine of popular humor, including a great deal of satire of the contemporary, social, and political scene.

Satire is a

genre of

literature, and sometimes

graphic and

performing arts,

in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to

ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, corporations,

government, or society itself into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive

social criticism, using

wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society.

A feature of satire is strong

irony or

sarcasm—"in satire, irony is militant"—but

parody,

burlesque,

exaggeration, juxtaposition, comparison, analogy, and

double entendre

are all frequently used in satirical speech and writing. This

"militant" irony or sarcasm often professes to approve of (or at least

accept as natural) the very things the satirist wishes to attack.

Satire is nowadays found in many artistic forms of expression, including

internet memes, literature, plays, commentary, television shows, and media such as lyrics.

Etymology and roots

The word satire comes from the

Latin word

satur and the subsequent phrase

lanx satura. Satur meant "full" but the juxtaposition with

lanx shifted the meaning to "miscellany or medley": the expression

lanx satura literally means "a full dish of various kinds of fruits".

The word

satura as used by

Quintilian, however, was used to denote only Roman verse satire, a strict genre that imposed

hexameter form, a narrower genre than what would be later intended as

satire. Quintilian famously said that

satura, that is a satire in hexameter verses, was a literary genre of wholly Roman origin (

satura tota nostra est).

He was aware of and commented on Greek satire, but at the time did not

label it as such, although today the origin of satire is considered to

be

Aristophanes' Old Comedy. The first critic to use the term "satire" in the modern broader sense was

Apuleius.

To Quintilian, the satire was a strict literary form, but the

term soon escaped from the original narrow definition. Robert Elliott

writes:

As soon as a noun enters the

domain of metaphor, as one modern scholar has pointed out, it clamors

for extension; and satura (which had had no verbal, adverbial, or

adjectival forms) was immediately broadened by appropriation from the

Greek word for “satyr” (satyros) and its derivatives. The odd result is

that the English “satire” comes from the Latin satura; but "satirize",

"satiric", etc., are of Greek origin. By about the 4th century AD the

writer of satires came to be known as satyricus; St. Jerome, for

example, was called by one of his enemies 'a satirist in prose'

('satyricus scriptor in prosa'). Subsequent orthographic modifications

obscured the Latin origin of the word satire: satura becomes satyra, and

in England, by the 16th century, it was written 'satyre.'

The word

satire derives from

satura, and its origin was not influenced by the

Greek mythological figure of the

satyr. In the 17th century, philologist

Isaac Casaubon was the first to dispute the etymology of satire from satyr, contrary to the belief up to that time.

Humor

| “

|

The rules of satire are such that it must do

more than make you laugh. No matter how amusing it is, it doesn't count

unless you find yourself wincing a little even as you chuckle.

|

”

|

|

|

Laughter is not an essential component of satire;

in fact there are types of satire that are not meant to be "funny" at

all. Conversely, not all humor, even on such topics as politics,

religion or art is necessarily "satirical", even when it uses the

satirical tools of irony, parody, and

burlesque.

Even light-hearted satire has a serious "after-taste": the organizers of the

Ig Nobel Prize describe this as "first make people laugh, and then make them think".

Social and psychological functions

Satire and

irony in some cases have been regarded as the most effective source to understand a society, the oldest form of

social study. They provide the keenest insights into a group's

collective psyche, reveal its deepest values and tastes, and the society's structures of power. Some authors have regarded satire as superior to non-comic and non-artistic disciplines like history or

anthropology. In a prominent example from

ancient Greece, philosopher

Plato, when asked by a friend for a book to understand Athenian society, referred him to the plays of

Aristophanes.

Historically, satire has satisfied the popular

need to

debunk and

ridicule the leading figures in politics, economy, religion and other prominent realms of

power. Satire confronts

public discourse and the

collective imaginary,

playing as a public opinion counterweight to power (be it political,

economic, religious, symbolic, or otherwise), by challenging leaders and

authorities. For instance, it forces administrations to clarify, amend

or establish their policies. Satire's job is to expose problems and

contradictions, and it's not obligated to solve them.

Karl Kraus set in the history of satire a prominent example of a satirist role as confronting public discourse.

For its nature and social role, satire has enjoyed in many

societies a special freedom license to mock prominent individuals and

institutions. The satiric impulse, and its ritualized expressions, carry out the function of resolving social tension. Institutions like the

ritual clowns, by giving expression to the

antisocial tendencies, represent a

safety valve which re-establishes equilibrium and health in the

collective imaginary, which are jeopardized by the

repressive aspects of society.

Classifications

Satire is a diverse genre which is complex to classify and define, with a wide range of satiric "modes".

Horatian, Juvenalian, Menippean

"Le satire e l'epistole di Q. Orazio Flacco", printed in 1814.

Satirical literature can commonly be categorized as either Horatian, Juvenalian, or

Menippean.

Horatian

Horatian satire, named for the Roman satirist

Horace

(65–8 BCE), playfully criticizes some social vice through gentle, mild,

and light hearted humor. Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus) wrote

Satires to gently ridicule the dominant opinions and "philosophical

beliefs of ancient Rome and Greece" (Rankin).

Rather than writing in harsh or accusing tones, he addressed issues

with humor and clever mockery. Horatian satire follows this same pattern

of "gently [ridiculing] the absurdities and follies of human beings"

(Drury).

It directs wit, exaggeration, and self-deprecating humour toward

what it identifies as folly, rather than evil. Horatian satire's

sympathetic tone is common in modern society.

A Horatian satirist's goal is to heal the situation with smiles,

rather than by anger. Horatian satire is a gentle reminder to take life

less seriously and evokes a wry smile.

A Horatian satirist makes fun of general human folly rather than

engaging in specific or personal attacks. Shamekia Thomas suggests, "In a

work using Horatian satire, readers often laugh at the characters in

the story who are the subject of mockery as well as themselves and

society for behaving in those ways."

Alexander Pope has been established as an author whose satire "heals with morals what it hurts with wit" (Green). Alexander Pope—and Horatian satire—attempt to teach.

Examples of Horatian satire:

- The Ig Nobel Prizes.

- Bierce, Ambrose, The Devil's Dictionary.

- Defoe, Daniel, The True-Born Englishman.

- The Savoy Operas of Gilbert and Sullivan.

- Trollope, Anthony, The Way We Live Now.

- Gogol, Nikolai, Dead Souls.

- Groening, Matthew "Matt", The Simpsons.

- Lewis, Clive Staples, The Screwtape Letters.

- Mercer, Richard ‘Rick’, The Rick Mercer Report.

- Pope, Alexander, The Rape of the Lock.

- Reiner, Rob, This Is Spinal Tap.

- Twain, Mark, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

- Ralston Saul, John, The Doubter's Companion: A Dictionary of Aggressive Common Sense.

Juvenalian

Juvenalian satire, named for the writings of the Roman satirist

Juvenal

(late first century – early second century AD), is more contemptuous

and abrasive than the Horatian. Juvenal disagreed with the opinions of

the public figures and institutions of the Republic and actively

attacked them through his literature. "He utilized the satirical tools

of exaggeration and parody to make his targets appear monstrous and

incompetent" (Podzemny).

Juvenal satire follows this same pattern of abrasively ridiculing

societal structures. Juvenal also, unlike Horace, attacked public

officials and governmental organizations through his satires, regarding

their opinions as not just wrong, but evil.

Following in this tradition, Juvenalian satire addresses

perceived social evil through scorn, outrage, and savage ridicule. This

form is often pessimistic, characterized by the use of irony, sarcasm,

moral indignation and personal invective, with less emphasis on humor.

Strongly polarized political satire can often be classified as

Juvenalian.

A Juvenal satirist's goal is generally to provoke some

sort of political or societal change because he sees his opponent or

object as evil or harmful. A Juvenal satirist mocks "societal structure, power, and civilization" (Thomas) by exaggerating the words or position of his opponent in order to jeopardize their opponent's reputation and/or power.

Jonathan Swift

has been established as an author who "borrowed heavily from Juvenal's

techniques in [his critique] of contemporary English society"

(Podzemny).

Examples of Juvenalian satire:

- Barnes, Julian, England, England.

- Beatty, Paul, The Sellout.

- Bradbury, Ray, Fahrenheit 451.

- Brooker, Charlie, Black Mirror.

- Bulgakov, Mikhail, Heart of a Dog.

- Burgess, Anthony, A Clockwork Orange.

- Burroughs, William, Naked Lunch.

- Byron, George Gordon, Lord, Don Juan.

- Cooke, Ebenezer, The

Sot-Weed Factor; or, A Voyage to Maryland,—a satire, in which is

described the laws, government, courts, and constitutions of the

country, and also the buildings, feasts, frolics, entertainments, and

drunken humors of the inhabitants in that part of America.

- Ellis, Bret Easton, American Psycho.

- Golding, William, Lord of the Flies.

- Hall, Joseph, Virgidemiarum.

- Heller, Joseph, Catch-22.

- Huxley, Aldous, Brave New World.

- Johnson, Samuel, London, an adaptation of Juvenal, Third Satire.

- Junius, Letters.

- Kubrick, Stanley, Dr. Strangelove.

- Mencken, HL, Libido for the Ugly.

- Morris, Chris, Brass Eye.

- ———, The Day Today.

- Orwell, George, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Orwell, George, Animal Farm.

- Palahniuk, Chuck, Fight Club.

- Swift, Jonathan, A Modest Proposal.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny, We.

- Voltaire, Candide.

Satire versus teasing

In the

history of theatre there has always been a conflict between engagement and disengagement on

politics and relevant issue, between satire and

grotesque on one side, and

jest with

teasing on the other.

Max Eastman defined the

spectrum

of satire in terms of "degrees of biting", as ranging from satire

proper at the hot-end, and "kidding" at the violet-end; Eastman adopted

the term kidding to denote what is just satirical in form, but is not

really firing at the target.

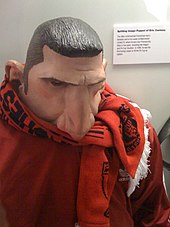

Nobel laureate satirical playwright

Dario Fo pointed out the difference between satire and teasing (

sfottò). Teasing is the

reactionary side of the

comic; it limits itself to a shallow

parody

of physical appearance. The side-effect of teasing is that it humanizes

and draws sympathy for the powerful individual towards which it is

directed. Satire instead uses the comic to go against power and its

oppressions, has a

subversive character, and a

moral dimension which draws judgement against its targets. Fo formulated an

operational criterion to tell real satire from

sfottò,

saying that real satire arouses an outraged and violent reaction, and

that the more they try to stop you, the better is the job you are doing.

Fo contends that, historically, people in positions of power have

welcomed and encouraged good-humoured buffoonery, while modern day

people in positions of power have tried to censor, ostracize and repress

satire.

Teasing (

sfottò) is an ancient form of simple

buffoonery,

a form of comedy without satire's subversive edge. Teasing includes

light and affectionate parody, good-humoured mockery, simple

one-dimensional poking fun, and benign spoofs. Teasing typically

consists of an

impersonation of someone monkeying around with his exterior attributes,

tics,

physical blemishes, voice and mannerisms, quirks, way of dressing and

walking, and/or the phrases he typically repeats. By contrast, teasing

never touches on the core issue, never makes a serious criticism judging

the target with

irony; it never harms the target's conduct,

ideology and position of power; it never undermines the perception of his morality and cultural dimension.

Sfottò directed towards a powerful individual makes him appear more human and draws sympathy towards him.

Hermann Göring propagated

jests and jokes against himself, with the aim of humanizing his image.

Classifications by topics

Types

of satire can also be classified according to the topics it deals with.

From the earliest times, at least since the plays of

Aristophanes, the primary topics of literary satire have been

politics,

religion and

sex.

This is partly because these are the most pressing problems that affect

anybody living in a society, and partly because these topics are

usually

taboo. Among these, politics in the broader sense is considered the pre-eminent topic of satire. Satire which targets the

clergy is a type of

political satire, while

religious satire is that which targets

religious beliefs. Satire on sex may overlap with

blue comedy,

off-color humor and

dick jokes.

Scatology has a long literary association with satire, as it is a classical mode of the

grotesque, the

grotesque body and the satiric grotesque.

Shit plays a fundamental role in satire because it symbolizes

death, the turd being "the ultimate dead object". The satirical comparison of individuals or institutions with human

excrement, exposes their "inherent inertness, corruption and dead-likeness". The

ritual clowns of

clown societies, like among the

Pueblo Indians, have ceremonies with

filth-eating. In other cultures,

sin-eating is an

apotropaic rite in which the sin-eater (also called filth-eater), by ingesting the food provided, takes "upon himself the sins of the departed". Satire about death overlaps with

black humor and

gallows humor.

Another classification by topics is the distinction between political satire, religious satire and satire of manners.

Political satire is sometimes called topical satire, satire of manners

is sometimes called satire of everyday life, and religious satire is

sometimes called philosophical satire.

Comedy of manners,

sometimes also called satire of manners, criticizes mode of life of

common people; political satire aims at behavior, manners of

politicians, and vices of political systems. Historically, comedy of

manners, which first appeared in British theater in 1620, has

uncritically accepted the social code of the upper classes. Comedy in general accepts the rules of the social game, while satire subverts them.

Classifications by medium

It appears also in graphic arts, music, sculpture, dance,

cartoon strips, and

graffiti. Examples are

Dada sculptures,

Pop Art works, music of

Gilbert and Sullivan and

Erik Satie,

punk and

rock music. In modern

media culture,

stand-up comedy is an enclave in which satire can be introduced into

mass media, challenging

mainstream discourse.

Comedy roasts, mock festivals, and stand-up comedians in nightclubs and concerts are the modern forms of ancient satiric rituals.

Development

Ancient Egypt

The satirical papyrus at the British Museum

Satirical ostraca showing a cat guarding geese, c.1120 BC, Egypt.

Figured ostracon showing a cat waiting on a mouse, Egypt

One of the earliest examples of what we might call satire,

The Satire of the Trades,

is in Egyptian writing from the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. The

text's apparent readers are students, tired of studying. It argues that

their lot as scribes is not only useful, but far superior to that of

the ordinary man. Scholars such as Helck think that the context was meant to be serious.

The

Papyrus Anastasi I

(late 2nd millennium BC) contains a satirical letter which first

praises the virtues of its recipient, but then mocks the reader's meagre

knowledge and achievements.

Ancient Greece

The

Greeks had no word for what later would be called "satire", although

the terms cynicism and parody were used. Modern critics call the

Greek playwright Aristophanes one of the best known early satirists: his plays are known for their critical political and

societal commentary, particularly for the

political satire by which he criticized the powerful

Cleon (as in

The Knights). He is also notable for the persecution he underwent. Aristophanes' plays turned upon images of filth and disease. His bawdy style was adopted by Greek dramatist-comedian

Menander. His early play

Drunkenness contains an attack on the politician

Callimedon.

The oldest form of satire still in use is the

Menippean satire by

Menippus of Gadara.

His own writings are lost. Examples from his admirers and imitators mix

seriousness and mockery in dialogues and present parodies before a

background of

diatribe. As in the case of Aristophanes plays, menippean satire turned upon images of filth and disease.

Roman world

The first Roman to discuss satire critically was

Quintilian, who invented the term to describe the writings of

Gaius Lucilius. The two most prominent and influential ancient Roman satirists are

Horace and

Juvenal, who wrote during the early days of the

Roman Empire. Other important satirists in ancient

Latin are Gaius Lucilius and

Persius.

Satire

in their work is much wider than in the modern sense of the word,

including fantastic and highly coloured humorous writing with little or

no real mocking intent. When Horace criticized

Augustus, he used

veiled ironic terms. In contrast,

Pliny reports that the 6th-century-BC poet

Hipponax wrote

satirae that were so cruel that the offended hanged themselves.

In the 2nd century AD,

Lucian wrote

True History, a book satirizing the clearly unrealistic travelogues/adventures written by

Ctesias,

Iambulus, and

Homer.

He states that he was surprised they expected people to believe their

lies, and stating that he, like they, has no actual knowledge or

experience, but shall now tell lies as if he did. He goes on to describe

a far more obviously extreme and unrealistic tale, involving

interplanetary exploration, war among alien life forms, and life inside a

200 mile long whale back in the terrestrial ocean, all intended to make

obvious the fallacies of books like

Indica and

The Odyssey.

Medieval Islamic world

Medieval

Arabic poetry included the satiric genre

hija. Satire was introduced into

Arabic prose literature by the

Afro-Arab author

Al-Jahiz in the 9th century. While dealing with serious topics in what are now known as

anthropology,

sociology and

psychology,

he introduced a satirical approach, "based on the premise that, however

serious the subject under review, it could be made more interesting and

thus achieve greater effect, if only one leavened the lump of solemnity

by the insertion of a few amusing anecdotes or by the throwing out of

some witty or paradoxical observations. He was well aware that, in

treating of new themes in his prose works, he would have to employ a

vocabulary of a nature more familiar in

hija, satirical poetry." For example, in one of his

zoological works, he satirized the preference for longer

human penis size, writing: "If the length of the penis were a sign of honor, then the

mule would belong to the (honorable tribe of)

Quraysh". Another satirical story based on this preference was an

Arabian Nights tale called "Ali with the Large Member".

In the 10th century, the writer

Tha'alibi recorded satirical poetry written by the Arabic poets As-Salami and Abu Dulaf, with As-Salami praising Abu Dulaf's

wide breadth of knowledge and then mocking his ability in all these subjects, and with Abu Dulaf responding back and satirizing As-Salami in return. An example of Arabic political satire included another 10th-century poet Jarir satirizing Farazdaq as "a transgressor of the

Sharia" and later Arabic poets in turn using the term "Farazdaq-like" as a form of political satire.

The terms "

comedy" and "satire" became synonymous after

Aristotle's

Poetics was translated into

Arabic in the

medieval Islamic world, where it was elaborated upon by

Islamic philosophers and writers, such as Abu Bischr, his pupil

Al-Farabi,

Avicenna, and

Averroes. Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from

Greek dramatic representation and instead identified it with

Arabic poetic themes and forms, such as

hija

(satirical poetry). They viewed comedy as simply the "art of

reprehension", and made no reference to light and cheerful events, or

troubled beginnings and happy endings, associated with classical Greek

comedy. After the

Latin translations of the 12th century, the term "comedy" thus gained a new semantic meaning in

Medieval literature.

Ubayd Zakani introduced satire in

Persian literature

during the 14th century. His work is noted for its satire and obscene

verses, often political or bawdy, and often cited in debates involving

homosexual practices. He wrote the

Resaleh-ye Delgosha, as well as

Akhlaq al-Ashraf ("Ethics of the Aristocracy") and the famous humorous fable

Masnavi Mush-O-Gorbeh

(Mouse and Cat), which was a political satire. His non-satirical

serious classical verses have also been regarded as very well written,

in league with the other great works of

Persian literature. Between 1905 and 1911,

Bibi Khatoon Astarabadi and other Iranian writers wrote notable satires.

Medieval Europe

Early modern western satire

Direct

social commentary via satire returned with a vengeance in the 16th century, when farcical texts such as the works of

François Rabelais tackled more serious issues (and incurred the wrath of the crown as a result).

The

Elizabethan

(i.e. 16th-century English) writers thought of satire as related to the

notoriously rude, coarse and sharp satyr play. Elizabethan "satire"

(typically in pamphlet form) therefore contains more straightforward

abuse than subtle irony. The French

Huguenot Isaac Casaubon

pointed out in 1605 that satire in the Roman fashion was something

altogether more civilised. Casaubon discovered and published

Quintilian's writing and presented the original meaning of the term

(satira, not satyr), and the sense of wittiness (reflecting the

"dishfull of fruits") became more important again. Seventeenth-century

English satire once again aimed at the "amendment of vices" (

Dryden).

In the 1590s a new wave of verse satire broke with the publication of

Hall's

Virgidemiarum, six books of verse satires targeting everything from literary fads to corrupt noblemen. Although

Donne

had already circulated satires in manuscript, Hall's was the first real

attempt in English at verse satire on the Juvenalian model. The success of his work combined with a national mood of disillusion in

the last years of Elizabeth's reign triggered an avalanche of

satire—much of it less conscious of classical models than Hall's — until

the fashion was brought to an abrupt stop by censorship.

Age of Enlightenment

'A Welch wedding' Satirical Cartoon c.1780

The

Age of Enlightenment,

an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries advocating

rationality, produced a great revival of satire in Britain. This was

fuelled by the rise of partisan politics, with the formalisation of the

Tory and

Whig parties—and also, in 1714, by the formation of the

Scriblerus Club, which included

Alexander Pope,

Jonathan Swift,

John Gay,

John Arbuthnot,

Robert Harley,

Thomas Parnell, and

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke.

This club included several of the notable satirists of

early-18th-century Britain. They focused their attention on Martinus

Scriblerus, "an invented learned fool... whose work they attributed all

that was tedious, narrow-minded, and pedantic in contemporary

scholarship".

In their hands astute and biting satire of institutions and individuals

became a popular weapon. The turn to the 18th century was characterized

by a switch from Horatian, soft, pseudo-satire, to biting "juvenal"

satire.

Jonathan Swift

was one of the greatest of Anglo-Irish satirists, and one of the first

to practise modern journalistic satire. For instance, In his

A Modest Proposal

Swift suggests that Irish peasants be encouraged to sell their own

children as food for the rich, as a solution to the "problem" of

poverty. His purpose is of course to attack indifference to the plight

of the desperately poor. In his book

Gulliver's Travels he writes about the flaws in human society in general and English society in particular.

John Dryden wrote an influential essay entitled "A Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire" that helped fix the definition of satire in the literary world. His satirical

Mac Flecknoe was written in response to a rivalry with

Thomas Shadwell and eventually inspired

Alexander Pope to write his satirical

The Rape of the Lock. Other satirical works by Pope include the

Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot.

Alexander Pope (b. May 21, 1688) was a satirist known for his Horatian satirist style and translation of the

Iliad. Famous throughout and after the

long 18th century, Pope died in 1744. Pope, in his

The Rape of the Lock,

is delicately chiding society in a sly but polished voice by holding up

a mirror to the follies and vanities of the upper class. Pope does not

actively attack the self-important pomp of the British aristocracy, but

rather presents it in such a way that gives the reader a new perspective

from which to easily view the actions in the story as foolish and

ridiculous. A mockery of the upper class, more delicate and lyrical than

brutal, Pope nonetheless is able to effectively illuminate the moral

degradation of society to the public.

The Rape of the Lock assimilates the masterful qualities of a heroic epic, such as the

Iliad, which Pope was translating at the time of writing

The Rape of the Lock. However, Pope applied these qualities satirically to a seemingly petty egotistical elitist quarrel to prove his point wryly.

The pictorial satire of

William Hogarth is a precursor to the development of

political cartoons in 18th-century England. The medium developed under the direction of its greatest exponent,

James Gillray from London.

With his satirical works calling the king (George III), prime ministers

and generals (especially Napoleon) to account, Gillray's wit and keen

sense of the ridiculous made him the pre-eminent

cartoonist of the era.

Ebenezer Cooke (1665–1732), author of "The Sot-Weed Factor" (1708), was among the first American colonialists to write literary satire.

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) and others followed, using satire to shape an emerging nation's culture through its sense of the ridiculous.

Satire in Victorian England

A Victorian satirical sketch depicting a gentleman's donkey race in 1852

Several satiric papers competed for the public's attention in the

Victorian era (1837–1901) and

Edwardian period, such as

Punch (1841) and

Fun (1861).

Perhaps the most enduring examples of Victorian satire, however, are to be found in the

Savoy Operas of

Gilbert and Sullivan. In fact, in

The Yeomen of the Guard,

a jester is given lines that paint a very neat picture of the method

and purpose of the satirist, and might almost be taken as a statement of

Gilbert's own intent:

- "I can set a braggart quailing with a quip,

- The upstart I can wither with a whim;

- He may wear a merry laugh upon his lip,

- But his laughter has an echo that is grim!"

Novelists such as

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) often used passages of satiric writing in their treatment of social issues.

Continuing the tradition of Swiftian journalistic satire,

Sidney Godolphin Osborne (1808-1889) was the most prominent writer of scathing "Letters to the Editor" of the

London Times. Famous in his day, he is now all but forgotten. His maternal grandfather

William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland was considered to be a possible candidate for the authorship of the

Junius

letters. If this were true, we can read Osborne as following in his

grandfather's satiric "Letters to the Editor" path. Osborne's satire was

so bitter and biting that at one point he received a public censure

from

Parliament's then Home Secretary Sir

James Graham.

Osborne wrote mostly in the Juvenalian mode over a wide range of topics

mostly centered on British government's and landlords' mistreatment of

poor farm workers and field laborers. He bitterly opposed the

New Poor Laws and was passionate on the subject of Great Britain's botched response to the

Irish Famine and its mistreatment of soldiers during the

Crimean War.

Later in the nineteenth century, in the United States,

Mark Twain (1835–1910) grew to become American's greatest satirist: his novel

Huckleberry Finn (1884) is set in the

antebellum

South, where the moral values Twain wishes to promote are completely

turned on their heads. His hero, Huck, is a rather simple but

goodhearted lad who is ashamed of the "sinful temptation" that leads him

to help a runaway

slave.

In fact his conscience, warped by the distorted moral world he has

grown up in, often bothers him most when he is at his best. He is

prepared to do good, believing it to be wrong.

20th-century satire

Karl Kraus is considered the first major European satirist since

Jonathan Swift. In 20th-century literature, satire was used by English authors such as

Aldous Huxley (1930s) and

George Orwell (1940s), which under the inspiration of

Zamyatin's Russian 1921 novel

We, made serious and even frightening commentaries on the dangers of the sweeping social changes taking place throughout Europe.

Anatoly Lunacharsky

wrote ‘Satire attains its greatest significance when a newly evolving

class creates an ideology considerably more advanced than that of the

ruling class, but has not yet developed to the point where it can

conquer it. Herein lies its truly great ability to triumph, its scorn

for its adversary and its hidden fear of it. Herein lies its venom, its

amazing energy of hate, and quite frequently, its grief, like a black

frame around glittering images. Herein lie its contradictions, and its

power.’ Many social critics of this same time in the United States, such as

Dorothy Parker and

H. L. Mencken,

used satire as their main weapon, and Mencken in particular is noted

for having said that "one horse-laugh is worth ten thousand

syllogisms" in the persuasion of the public to accept a criticism. Novelist

Sinclair Lewis was known for his satirical stories such as

Main Street (1920),

Babbitt (1922),

Elmer Gantry (1927; dedicated by Lewis to H. L. Menchen), and

It Can't Happen Here (1935), and his books often explored and satirized contemporary American values. The film

The Great Dictator (1940) by

Charlie Chaplin is itself a parody of

Adolf Hitler; Chaplin later declared that he would have not made the film if he had known about the

concentration camps.

Benzino Napaloni and Adenoid Hynkel in The Great Dictator (1940). Chaplin later declared that he would have not made the film if he had known about the concentration camps.

In the United States 1950s, satire was introduced into American

stand-up comedy most prominently by

Lenny Bruce and

Mort Sahl. As they challenged the

taboos and

conventional wisdom of the time, were ostracized by the mass media establishment as

sick comedians. In the same period,

Paul Krassner's magazine

The Realist began publication, to become immensely popular during the 1960s and early 1970s among people in the

counterculture; it had articles and cartoons that were savage, biting satires of politicians such as

Lyndon Johnson and

Richard Nixon, the

Vietnam War, the

Cold War and the

War on Drugs. This baton was also carried by the original

National Lampoon magazine, edited by

Doug Kenney and

Henry Beard and featuring blistering satire written by

Michael O'Donoghue,

P.J. O'Rourke, and

Tony Hendra, among others. Prominent satiric stand-up comedian

George Carlin acknowledged the influence

The Realist had in his 1970s conversion to a satiric comedian.

Contemporary satire

Contemporary popular usage of the term "satire" is often very imprecise. While satire often uses

caricature and

parody,

by no means all uses of these or other humorous devices are satiric.

Refer to the careful definition of satire that heads this article.

Stephen Colbert's television program,

The Colbert Report (2005–14), is instructive in the methods of contemporary American satire.

Colbert's character

is an opinionated and self-righteous commentator who, in his TV

interviews, interrupts people, points and wags his finger at them, and

"unwittingly" uses a number of logical fallacies. In doing so, he

demonstrates the principle of modern American political satire: the

ridicule of the actions of politicians and other public figures by

taking all their statements and purported beliefs to their furthest

(supposedly) logical conclusion, thus revealing their perceived

hypocrisy or absurdity.

The American sketch comedy television show

Saturday Night Live

is also known for its satirical impressions and parodies of prominent

persons and politicians, among some of the most notable, their parodies

of U.S. political figures

Hillary Clinton and of

Sarah Palin.

Other political satire includes various political causes in the past, including the relatively successful

Polish Beer-Lovers' Party and the joke political candidates Molly the Dog and

Brian Miner.

In the United Kingdom, a popular modern satirist is Sir

Terry Pratchett, author of the internationally best-selling

Discworld book series. One of the most well-known and controversial British satirists is

Chris Morris, co-writer and director of

Four Lions.

In Canada, satire has become an important part of the comedy scene.

Stephen Leacock

was one of the best known early Canadian satirists, and in the early

20th century, he achieved fame by targeting the attitudes of small town

life. In more recent years, Canada has had several prominent satirical

television series and radio shows. Some, including

CODCO,

The Royal Canadian Air Farce,

This Is That, and

This Hour Has 22 Minutes deal directly with current news stories and political figures, while others, like

History Bites present contemporary social satire in the context of events and figures in history. The Canadian organization

Canada News Network provides commentary on contemporary news events that are primarily Canadian in nature. Canadian songwriter

Nancy White uses music as the vehicle for her satire, and her comic folk songs are regularly played on

CBC Radio.

Cartoonists often use satire as well as straight humour.

Al Capp's satirical

comic strip Li'l Abner was censored in September 1947. The controversy, as reported in

Time,

centered on Capp's portrayal of the US Senate. Said Edward Leech of

Scripps-Howard, "We don't think it is good editing or sound citizenship

to picture the Senate as an assemblage of freaks and crooks... boobs and

undesirables."

Walt Kelly's

Pogo was likewise censored in 1952 over his overt satire of

Senator Joe McCarthy, caricatured in his comic strip as "Simple J. Malarky".

Garry Trudeau, whose

comic strip Doonesbury

focuses on satire of the political system, and provides a trademark

cynical view on national events. Trudeau exemplifies humor mixed with

criticism. For example, the character

Mark Slackmeyer

lamented that because he was not legally married to his partner, he was

deprived of the "exquisite agony" of experiencing a nasty and painful

divorce like heterosexuals. This, of course, satirized the claim that

gay unions would denigrate the sanctity of heterosexual marriage.

Like some literary predecessors, many recent television satires contain strong elements of parody and

caricature; for instance, the popular animated series

The Simpsons and

South Park

both parody modern family and social life by taking their assumptions

to the extreme; both have led to the creation of similar series. As well

as the purely humorous effect of this sort of thing, they often

strongly criticise various phenomena in politics, economic life,

religion and many other aspects of society, and thus qualify as

satirical. Due to their animated nature, these shows can easily use

images of public figures and generally have greater freedom to do so

than conventional shows using live actors.

News satire

is also a very popular form of contemporary satire, appearing in as

wide an array of formats as the news media itself: print (e.g.

The Onion,

Canada News Network,

Private Eye), "Not Your Homepage," radio (e.g.

On the Hour), television (e.g.

The Day Today,

The Daily Show,

Brass Eye) and the web (e.g.

Mindry.in, The Fruit Dish,

Scunt News,

Faking News,

El Koshary Today, The Giant Napkin, Unconfirmed Sources and The

Onion's website). Other satires are on the

list of satirists and satires. Another internet-driven form of satire is to lampoon bad internet performers. An example of this is the

Internet meme character

Miranda Sings.

In an interview with

Wikinews, Sean Mills, President of

The Onion,

said angry letters about their news parody always carried the same

message. "It's whatever affects that person", said Mills. "So it's like,

'I love it when you make a joke about murder or rape, but if you talk

about cancer, well my brother has cancer and that's not funny to me.' Or

someone else can say, 'Cancer's

hilarious, but don't talk about

rape because my cousin got raped.' Those are rather extreme examples,

but if it affects somebody personally, they tend to be more sensitive

about it."

Zhou Libo, a comedian from

Shanghai,

is the most popular satirist in China. His humour has interested

middle-class people and has sold out shows ever since his rise to fame.

Techniques

Literary satire is usually written out of earlier satiric works,

reprising previous conventions, commonplaces, stance, situations and tones of voice.

Exaggeration is one of the most common satirical techniques. Contrarily

diminution is also a satirical technique.

Legal status

For

its nature and social role, satire has enjoyed in many societies a

special freedom license to mock prominent individuals and institutions. In Germany and Italy satire is protected by the constitution.

Since satire belongs to the realm of

art and artistic expression, it benefits from broader lawfulness limits than mere

freedom of information of journalistic kind.

In some countries a specific "right to satire" is recognized and its

limits go beyond the "right to report" of journalism and even the "right

to criticize". Satire benefits not only of the protection to

freedom of speech, but also to that to

culture, and that to scientific and artistic production.

Australia

In September 2017

The Juice Media

received an e-mail from the Australian National Symbols Officer

requesting that the use of a satirical logo, called the "Coat of Harms"

based on the

Australian Coat of Arms, no longer be used as they had received complaints from the members of the public. Coincidentally 5 days later a Bill was proposed to

Australian parliament to amend the

Criminal Code Act 1995. If successfully passed those found to be in breach of the new amendment can face 2–5 years imprisonment.

As of June 2018, the Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 was before the

Australian Senate with the

third reading moved 10 May 2018.

Censorship and criticism

Descriptions of satire's biting effect on its target include 'venomous', 'cutting', 'stinging',

vitriol. Because satire often combines anger and humor, as well as the

fact that it addresses and calls into question many controversial

issues, it can be profoundly disturbing.

Typical arguments

Because

it is essentially ironic or sarcastic, satire is often misunderstood. A

typical misunderstanding is to confuse the satirist with his

persona.

Bad taste

Common uncomprehending responses to satire include revulsion (accusations of

poor taste,

or that "it's just not funny" for instance) and the idea that the

satirist actually does support the ideas, policies, or people he is

attacking. For instance, at the time of its publication, many people

misunderstood Swift's purpose in

A Modest Proposal, assuming it to be a serious recommendation of economically motivated cannibalism.

Targeting the victim

Some critics of

Mark Twain see

Huckleberry Finn as

racist

and offensive, missing the point that its author clearly intended it to

be satire (racism being in fact only one of a number of Mark Twain's

known concerns attacked in

Huckleberry Finn). This same misconception was suffered by the main character of the 1960s British television comedy satire

Till Death Us Do Part. The character of

Alf Garnett (played by

Warren Mitchell) was created to poke fun at the kind of narrow-minded, racist,

little Englander that Garnett represented. Instead, his character became a sort of

anti-hero to people who actually agreed with his views. (The same situation occurred with

Archie Bunker in American TV show

All in the Family, a character derived directly from Garnett.)

The Australian satirical television comedy show

The Chaser's War on Everything

has suffered repeated attacks based on various perceived

interpretations of the "target" of its attacks. The "Make a Realistic

Wish Foundation" sketch (June 2009), which attacked in classical satiric

fashion the heartlessness of people who are reluctant to donate to

charities, was widely interpreted as an attack on the

Make a Wish Foundation, or even the terminally ill children helped by that organization.

Prime Minister of the time

Kevin Rudd

stated that The Chaser team "should hang their heads in shame". He went

on to say that "I didn't see that but it's been described to me. ...But

having a go at kids with a terminal illness is really beyond the pale,

absolutely beyond the pale." Television station management suspended the show for two weeks and reduced the third season to eight episodes.

Romantic prejudice

The romantic prejudice against satire is the belief spread by the

romantic movement that satire is something unworthy of serious attention; this prejudice has held considerable influence to this day.

Such prejudice extends to humor and everything that arouses laughter,

which are often underestimated as frivolous and unworthy of serious

study. For instance, humor is generally neglected as a topic of anthropological research and teaching.

History of opposition toward notable satires

Because satire criticises in an ironic, essentially indirect way, it frequently escapes

censorship

in a way more direct criticism might not. Periodically, however, it

runs into serious opposition, and people in power who perceive

themselves as attacked attempt to censor it or prosecute its

practitioners. In a classic example,

Aristophanes was persecuted by the

demagogue Cleon.

1599 book ban

The motives for the ban are obscure, particularly since some of

the books banned had been licensed by the same authorities less than a

year earlier. Various scholars have argued that the target was

obscenity, libel, or sedition. It seems likely that lingering anxiety

about the

Martin Marprelate controversy, in which the bishops themselves had employed satirists, played a role; both

Thomas Nashe and

Gabriel Harvey,

two of the key figures in that controversy, suffered a complete ban on

all their works. In the event, though, the ban was little enforced, even

by the licensing authority itself.

21st-century polemics

In 2008, popular South African cartoonist and satirist

Jonathan Shapiro (who is published under the pen name Zapiro) came under fire for depicting then-president of the

ANC Jacob Zuma in the act of undressing in preparation for the implied rape of 'Lady Justice' which is held down by Zuma loyalists.

The cartoon was drawn in response to Zuma's efforts to duck corruption

charges, and the controversy was heightened by the fact that Zuma was

himself acquitted of

rape in May 2006. In February 2009, the

South African Broadcasting Corporation, viewed by some opposition parties as the mouthpiece of the governing ANC, shelved a satirical TV show created by Shapiro,

and in May 2009 the broadcaster pulled a documentary about political

satire (featuring Shapiro among others) for the second time, hours

before scheduled broadcast.

Apartheid South Africa also had a long history of censorship.

On December 29, 2009, Samsung sued

Mike Breen, and the

Korea Times for $1 million, claiming criminal defamation over a satirical column published on Christmas Day, 2009.

On April 29, 2015, the

UK Independence Party (UKIP) requested

Kent Police investigate the

BBC, claiming that comments made about Party leader

Nigel Farage by a panelist on the comedy show

Have I Got News For You

might hinder his chances of success in the general election (which

would take place a week later), and claimed the BBC breached the

Representation of the People Act.

Kent Police rebuffed the request to open an investigation, and the BBC

released a statement, "Britain has a proud tradition of satire, and

everyone knows that the contributors on

Have I Got News for You regularly make jokes at the expense of politicians of all parties."

Satirical prophecy

Satire is occasionally prophetic: the jokes precede actual events. Among the eminent examples are:

- The 1784 presaging of modern daylight saving time, later actually proposed in 1907. While an American envoy to France, Benjamin Franklin anonymously published a letter in 1784 suggesting that Parisians economize on candles by arising earlier to use morning sunlight.

- In the 1920s, an English cartoonist imagined a laughable thing for the time: a hotel for cars. He drew a multi-story car park.

- The second episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus, which debuted in 1969, featured a skit entitled "The Mouse Problem"

(meant to satirize contemporary media exposés on homosexuality), which

depicted a cultural phenomenon eerily similar to modern furry fandom (which did not become widespread until the 1980s, over a decade after the skit was first aired).

- The comedy film Americathon,

released in 1979 and set in the United States of 1998, predicted a

number of trends and events that would eventually unfold in the near

future, including an American debt crisis, Chinese capitalism, the fall of the Soviet Union, terrorism aimed at the civilian population, a presidential sex scandal, and the popularity of reality shows.

- In January 2001, a satirical news article in The Onion, entitled "Our Long National Nightmare of Peace and Prosperity Is Finally Over"

had newly elected President George Bush vowing to "develop new and

expensive weapons technologies" and to "engage in at least one Gulf

War-level armed conflict in the next four years". Furthermore, he would

"bring back economic stagnation by implementing substantial tax cuts,

which would lead to a recession". This prophesied the Iraq War and to the Bush tax cuts.

- In 1975, the first episode of Saturday Night Live included an ad for a triple blade razor called the Triple-Trac; in 2001, Gillette introduced the Mach3. In 2004, The Onion satirized Schick

and Gillette's marketing of ever-increasingly multi-blade razors with a

mock article proclaiming Gillette will now introduce a five-blade

razor. In 2006, Gillette released the Gillette Fusion, a five-blade razor.

- After the Iran nuclear deal in 2015, The Onion

ran an article with the headline "U.S. Soothes Upset Netanyahu With

Shipment Of Ballistic Missiles". Sure enough, reports broke the next day

of the Obama administration offering military upgrades to Israel in the

wake of the deal.

- In July 2016, The Simpsons released the most recent in a string of satirical references to a potential Donald Trump presidency. Other media sources, including the popular film Back to the Future Part II have also made similar satirical references.