Cover of the first edition, featuring the painting Pizarro seizing the Inca of Peru by John Everett Millais

| |

| Author | Jared Diamond |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Geography, social evolution, ethnology, cultural diffusion |

| Published | 1997 (W. W. Norton) |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback), audio CD, audio cassette, audio download |

| Pages | 480 pages (1st edition, hardcover) |

| ISBN | 0-393-03891-2 (1st edition, hardcover) |

| OCLC | 35792200 |

| 303.4 21 | |

| LC Class | HM206 .D48 1997 |

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (also titled Guns, Germs and Steel: A short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years) is a 1997 transdisciplinary non-fiction book by Jared Diamond, professor of geography and physiology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In 1998, Guns, Germs, and Steel won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction and the Aventis Prize for Best Science Book. A documentary based on the book, and produced by the National Geographic Society, was broadcast on PBS in July 2005.

The book attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians (for example, written language or the development among Eurasians of resistance to endemic diseases), he asserts that these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on societies and cultures (for example, by facilitating commerce and trade between different cultures) and were not inherent in the Eurasian genomes.

Synopsis

Diamond realized the same question seemed to apply elsewhere: "People of Eurasian origin ... dominate ... the world in wealth and power." Other peoples, after having thrown off colonial domination, still lag in wealth and power. Still others, he says, "have been decimated, subjugated, and in some cases even exterminated by European colonialists." (p. 15)

The peoples of other continents (sub-Saharan Africans, Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans, and the original inhabitants of tropical Southeast Asia) have been largely conquered, displaced and in some extreme cases – referring to Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians, and South Africa's indigenous Khoisan peoples – largely exterminated by farm-based societies such as Eurasians and Bantu. He believes this is due to these societies' technologic and immunologic advantages, stemming from the early rise of agriculture after the last Ice Age.

Title

The book's title is a reference to the means by which farm-based societies conquered populations of other areas and maintained dominance, despite sometimes being vastly outnumbered – superior weapons provided immediate military superiority (guns); Eurasian diseases weakened and reduced local populations, who had no immunity, making it easier to maintain control over them (germs); and durable means of transport (steel) enabled imperialism.Diamond argues geographic, climatic and environmental characteristics which favored early development of stable agricultural societies ultimately led to immunity to diseases endemic in agricultural animals and the development of powerful, organized states capable of dominating others.

Outline of theory

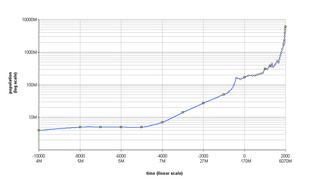

Diamond argues that Eurasian civilization is not so much a product of ingenuity, but of opportunity and necessity. That is, civilization is not created out of superior intelligence, but is the result of a chain of developments, each made possible by certain preconditions.The first step towards civilization is the move from nomadic hunter-gatherer to rooted agrarian society. Several conditions are necessary for this transition to occur: access to high-carbohydrate vegetation that endures storage; a climate dry enough to allow storage; and access to animals docile enough for domestication and versatile enough to survive captivity. Control of crops and livestock leads to food surpluses. Surpluses free people to specialize in activities other than sustenance and support population growth. The combination of specialization and population growth leads to the accumulation of social and technologic innovations which build on each other. Large societies develop ruling classes and supporting bureaucracies, which in turn lead to the organization of nation-states and empires.

Although agriculture arose in several parts of the world, Eurasia gained an early advantage due to the greater availability of suitable plant and animal species for domestication. In particular, Eurasia has barley, two varieties of wheat, and three protein-rich pulses for food; flax for textiles; and goats, sheep, and cattle. Eurasian grains were richer in protein, easier to sow, and easier to store than American maize or tropical bananas.

As early Western Asian civilizations began to trade, they found additional useful animals in adjacent territories, most notably horses and donkeys for use in transport. Diamond identifies 13 species of large animals over 100 pounds (45 kg) domesticated in Eurasia, compared with just one in South America (counting the llama and alpaca as breeds within the same species) and none at all in the rest of the world. Australia and North America suffered from a lack of useful animals due to extinction, probably by human hunting, shortly after the end of the Pleistocene, whilst the only domesticated animals in New Guinea came from the East Asian mainland during the Austronesian settlement some 4,000–5,000 years ago. Sub-Saharan biological relatives of the horse including zebras and onagers proved untameable; and although African elephants can be tamed, it is very difficult to breed them in captivity; Diamond describes the small number of domesticated species (14 out of 148 "candidates") as an instance of the Anna Karenina principle: many promising species have just one of several significant difficulties that prevent domestication. He also makes the intriguing argument that all large mammals that could be domesticated, have been.

Eurasians domesticated goats and sheep for hides, clothing, and cheese; cows for milk; bullocks for tillage of fields and transport; and benign animals such as pigs and chickens. Large domestic animals such as horses and camels offered the considerable military and economic advantages of mobile transport.

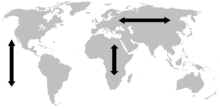

Continental axes according to Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel.

Eurasia's large landmass and long east-west distance increased these advantages. Its large area provided it with more plant and animal species suitable for domestication, and allowed its people to exchange both innovations and diseases. Its east-west orientation allowed breeds domesticated in one part of the continent to be used elsewhere through similarities in climate and the cycle of seasons. The Americas had difficulty adapting crops domesticated at one latitude for use at other latitudes (and, in North America, adapting crops from one side of the Rocky Mountains to the other). Similarly, Africa was fragmented by its extreme variations in climate from north to south: crops and animals that flourished in one area never reached other areas where they could have flourished, because they could not survive the intervening environment. Europe was the ultimate beneficiary of Eurasia's east-west orientation: in the first millennium BCE, the Mediterranean areas of Europe adopted Southwestern Asia's animals, plants, and agricultural techniques; in the first millennium CE, the rest of Europe followed suit.

The plentiful supply of food and the dense populations that it supported made division of labor possible. The rise of nonfarming specialists such as craftsmen and scribes accelerated economic growth and technological progress. These economic and technological advantages eventually enabled Europeans to conquer the peoples of the other continents in recent centuries by using the guns and steel of the book's title.

Eurasia's dense populations, high levels of trade, and living in close proximity to livestock resulted in widespread transmission of diseases, including from animals to humans. Smallpox, measles, and influenza were the result of close proximity between dense populations of animals and humans. Natural selection forced Eurasians to develop immunity to a wide range of pathogens. When Europeans made contact with the Americas, European diseases (to which Americans had no immunity) ravaged the indigenous American population, rather than the other way around (the "trade" in diseases was a little more balanced in Africa and southern Asia: endemic malaria and yellow fever made these regions notorious as the "white man's grave"; and syphilis may have originated in the Americas). The European diseases – the germs of the book's title – decimated indigenous populations so that relatively small numbers of Europeans could maintain their dominance.

Diamond also proposes geographical explanations for why western European societies, rather than other Eurasian powers such as China, have been the dominant colonizers, claiming Europe's geography favored balkanization into smaller, closer, nation-states, bordered by natural barriers of mountains, rivers, and coastline. Threats posed by immediate neighbours ensured governments that suppressed economic and technological progress soon corrected their mistakes or were outcompeted relatively quickly, whilst the region's leading powers changed over time. Other advanced cultures developed in areas whose geography was conducive to large, monolithic, isolated empires, without competitors that might have forced the nation to reverse mistaken policies such as China banning the building of ocean-going ships. Western Europe also benefited from a more temperate climate than Southwestern Asia where intense agriculture ultimately damaged the environment, encouraged desertification, and hurt soil fertility.

Agriculture

Guns, Germs, and Steel argues that cities require an ample supply of food, and thus are dependent on agriculture. As farmers do the work of providing food, division of labor allows others freedom to pursue other functions, such as mining and literacy.The crucial trap for the development of agriculture is the availability of wild edible plant species suitable for domestication. Farming arose early in the Fertile Crescent since the area had an abundance of wild wheat and pulse species that were nutritious and easy to domesticate. In contrast, American farmers had to struggle to develop corn as a useful food from its probable wild ancestor, teosinte.

Also important to the transition from hunter-gatherer to city-dwelling agrarian societies was the presence of 'large' domesticable animals, raised for meat, work, and long-distance communication. Diamond identifies a mere 14 domesticated large mammal species worldwide. The five most useful (cow, horse, sheep, goat, and pig) are all descendants of species endemic to Eurasia. Of the remaining nine, only two (the llama and alpaca both of South America) are indigenous to a land outside the temperate region of Eurasia.

Due to the Anna Karenina principle, surprisingly few animals are suitable for domestication. Diamond identifies six criteria including the animal being sufficiently docile, gregarious, willing to breed in captivity and having a social dominance hierarchy. Therefore, none of the many African mammals such as the zebra, antelope, cape buffalo, and African elephant were ever domesticated (although some can be tamed, they are not easily bred in captivity). The Holocene extinction event eliminated many of the megafauna that, had they survived, might have become candidate species, and Diamond argues that the pattern of extinction is more severe on continents where animals that had no prior experience of humans were exposed to humans who already possessed advanced hunting techniques (e.g. the Americas and Australia).

Smaller domesticable animals such as dogs, cats, chickens, and guinea pigs may be valuable in various ways to an agricultural society, but will not be adequate in themselves to sustain large-scale agrarian society. An important example is the use of larger animals such as cattle and horses in plowing land, allowing for much greater crop productivity and the ability to farm a much wider variety of land and soil types than would be possible solely by human muscle power. Large domestic animals also have an important role in the transportation of goods and people over long distances, giving the societies that possess them considerable military and economic advantages.

Geography

Diamond also argues that geography shaped human migration, not simply by making travel difficult (particularly by latitude), but by how climates affect where domesticable animals can easily travel and where crops can ideally grow easily due to the sun.The dominant Out of Africa theory holds that modern humans developed east of the Great Rift Valley of the African continent at one time or another. The Sahara kept people from migrating north to the Fertile Crescent, until later when the Nile River valley became accommodating.

Diamond continues to describe the story of human development up to the modern era, through the rapid development of technology, and its dire consequences on hunter-gathering cultures around the world.

Diamond touches on why the dominant powers of the last 500 years have been West European rather than East Asian (especially Chinese). The Asian areas in which big civilizations arose had geographical features conducive to the formation of large, stable, isolated empires which faced no external pressure to change which led to stagnation. Europe's many natural barriers allowed the development of competing nation-states. Such competition forced the European nations to encourage innovation and avoid technological stagnation.

Germs

In the later context of the European colonization of the Americas, 95% of the indigenous populations are believed to have been killed off by diseases brought by the Europeans. Many were killed by infectious diseases such as smallpox and measles. Similar circumstances were observed in the History of Australia (1788-1850) and in History of South Africa. Aboriginal Australians and the Khoikhoi population were decimated by smallpox, measles, influenza and other diseases.How was it then that diseases native to the American continents did not kill off Europeans? Diamond posits that the most of these diseases were only developed and sustained in large dense populations in villages and cities; he also states most epidemic diseases evolve from similar diseases of domestic animals. The combined effect of the increased population densities supported by agriculture, and of close human proximity to domesticated animals leading to animal diseases infecting humans, resulted in European societies acquiring a much richer collection of dangerous pathogens to which European people had acquired immunity through natural selection (see the Black Death and other epidemics) during a longer time than was the case for Native American hunter-gatherers and farmers.

He mentions the tropical diseases (mainly malaria) that limited European penetration into Africa as an exception. Endemic infectious diseases were also barriers to European colonisation of Southeast Asia and New Guinea.

Success and failure

Guns, Germs, and Steel focuses on why some populations succeeded. His later book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, focuses on environmental and other factors that have caused some populations to fail. It is a cautionary book.Intellectual background

In the 1930s, the Annales School in France undertook the study of long-term historical structures by using a synthesis of geography, history, and sociology. Scholars examined the impact of geography, climate, and land use. Although geography had been nearly eliminated as an academic discipline in the United States after the 1960s, several geography-based historical theories were published in the 1990s.In 1991, Jared Diamond already considered the question of "why is it that the Eurasians came to dominate other cultures?" in The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal (part four).

Reception

Guns, Germs, and Steel won the 1997 Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science. In 1998, it won the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction, in recognition of its powerful synthesis of many disciplines, and the Royal Society's Rhône-Poulenc Prize for Science Books. The National Geographic Society produced a documentary of the same title based on the book that was broadcast on PBS in July 2005.Academic reviews

In a review of Guns, Germs, and Steel that ultimately commended the book, historian Tom Tomlinson wrote, "Given the magnitude of the task he has set himself, it is inevitable that Professor Diamond uses very broad brush-strokes to fill in his argument."Another historian, professor J. R. McNeill, was on the whole complimentary, but thought Diamond oversold geography as an explanation for history and underemphasized cultural autonomy.

In his last book published in 2000, the anthropologist and geographer James Morris Blaut criticized Guns, Germs, and Steel, among other reasons, for reviving the theory of environmental determinism, and described Diamond as an example of a modern Eurocentric historian. Blaut criticizes Diamond's loose use of the terms "Eurasia" and "innovative", which he believes misleads the reader into presuming that Western Europe is responsible for technological inventions that arose in the Middle East and Asia.

Harvard International Relations (IR) scholar Stephen Walt called the book "an exhilarating read" and put it on a list of the ten books every IR student should read.

Berkeley economist Brad DeLong describes the book as a "work of complete and total genius".

John Brätland, an Austrian school economist of the U.S. Department of the Interior, complained in a Journal of Libertarian Studies article that Guns, Germs, and Steel entirely neglects individual action, concentrating solely on the centralized state; fails to understand how societies form (assessing that societies do not exist or form without a strong government); and ignores various economical institutions, such as monetary exchange that would allow societies to "rationally reckon scarcities and the value of actions required to replace what is depleted through human use". Instead, the author concludes that because there was no sophisticated division of labor, private property rights, and monetary exchange, societies like that on Easter Island could never progress from the nomadic stage to a complex society. Those factors, according to Brätland, are crucial, and at the same time neglected by Diamond.

Anthropologist Jason Antrosio describes Guns, Germs, and Steel as a form of "academic porn". Diamond's account makes all the factors of European domination a product of a distant and accidental history and has almost no role for human agency–the ability people have to make decisions and influence outcomes. Europeans become inadvertent, accidental conquerors. Natives succumb passively to their fate. "Jared Diamond has done a huge disservice to the telling of human history. He has tremendously distorted the role of domestication and agriculture in that history. Unfortunately his story-telling abilities are so compelling that he has seduced a generation of college-educated readers."

Other critiques have been made over the author's position on the agricultural revolution. The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture is not necessarily a one way process. It has been argued that hunting and gathering represents an adaptive strategy, which may still be exploited, if necessary, when environmental change causes extreme food stress for agriculturalists. In fact, it is sometimes difficult to draw a clear line between agricultural and hunter-gatherer societies, especially since the widespread adoption of agriculture and resulting cultural diffusion that has occurred in the last 10,000 years.

Publication

Guns, Germs, and Steel was first published by W. W. Norton in March 1997. It was subsequently published in Great Britain under the title Guns, Germs, and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years by Vintage in 1998 (ISBN 978-0099302780). It was a selection of Book of the Month Club, History Book Club, Quality Paperback Book Club, and Newbridge Book Club.In 2003 and 2007, the author published new English-language editions that included information collected since the previous editions. The new information did not change any of the original edition's conclusions.