Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Europe and Latin America, impeachment tends to be confined to ministerial officials as the unique nature of their positions may place ministers beyond the reach of the law to prosecute, or their misconduct is not codified into law as an offense except through the unique expectations of their high office. Both "peers and commoners" have been subject to the process, however. From 1990 to 2020, there have been at least 272 impeachment charges against 132 different heads of state in 63 countries. Most democracies (with the notable exception of the United States) involve the courts (often a national constitutional court) in some way.

In Latin America, which includes almost 40% of the world's presidential systems, ten presidents from six countries were removed from office by their national legislatures via impeachments or declarations of incapacity between 1978 and 2019.

National legislations differ regarding both the consequences and definition of impeachment, but the intent is nearly always to expeditiously vacate the office. In most nations the process begins in the lower house of a bicameral assembly who bring charges of misconduct, then the upper house administers an impeachment trial and sentencing. Most commonly, an official is considered impeached after the house votes to accept the charges, and impeachment itself does not remove the official from office.

Because impeachment involves a departure from the normal constitutional procedures by which individuals achieve high office (election, ratification, or appointment) and because it generally requires a supermajority, they are usually reserved for those deemed to have committed serious abuses of their office. In the United States, for example, impeachment at the federal level is limited to those who may have committed "Treason, Bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors"—the latter phrase referring to offenses against the government or the constitution, grave abuses of power, violations of the public trust, or other political crimes, even if not indictable criminal offenses. Under the United States Constitution, the House of Representatives has the sole power of impeachments while the Senate has the sole power to try impeachments (i.e., to acquit or convict); the validity of an impeachment trial is a political question that is nonjusticiable (i.e.., is not reviewable by the courts). In the United States, impeachment is a remedial rather than penal process, intended to "effectively 'maintain constitutional government' by removing individuals unfit for office"; persons subject to impeachment and removal remain "liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law."

Impeachment is provided for in the constitutional laws of many countries including Brazil, France, India, Ireland, the Philippines, Russia, South Korea, and the United States. It is distinct from the motion of no confidence procedure available in some countries whereby a motion of censure can be used to remove a government and its ministers from office. Such a procedure is not applicable in countries with presidential forms of government like the United States.

Etymology and history

The word "impeachment" likely derives from Old French empeechier from Latin word impedīre expressing the idea of catching or ensnaring by the 'foot' (pes, pedis), and has analogues in the modern French verb empêcher (to prevent) and the modern English impede. Medieval popular etymology also associated it (wrongly) with derivations from the Latin impetere (to attack).

The process was first used by the English "Good Parliament" against William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer in the second half of the 14th century. Following the English example, the constitutions of Virginia (1776), Massachusetts (1780) and other states thereafter adopted the impeachment mechanism, but they restricted the punishment to removal of the official from office.

In West Africa, Kings of the Ashanti Empire who violated any of the oaths taken during their enstoolment were destooled by Kingmakers. For instance, if a king punished citizens arbitrarily or was exposed to be corrupt, he would be destooled. Destoolment entailed Kingmakers removing the sandals of the king and bumping his buttocks on the ground three times. Once destooled from office, his sanctity and thus reverence were lost, as he cannot exercise any powers he had as king; this includes Chief administrator, Judge, and Military Commander. The now previous king is disposed of the Stool, swords and other regalia which symbolize his office and authority. He also loses the position as custodian of the land. However, despite being destooled from office, the king remains a member of the Royal Family from which he was elected.

In various jurisdictions

Brazil

In Brazil, as in most other Latin American countries, "impeachment" refers to the definitive removal from office. The president of Brazil may be provisionally removed from office by the Chamber of Deputies and then tried and definitely removed from office by the Federal Senate. The Brazilian Constitution requires that two-thirds of the Deputies vote in favor of the opening of the impeachment process of the President and that two-thirds of the Senators vote for impeachment. State governors and municipal mayors can also be impeached by the respective legislative bodies. Article 2 of Law no. 1.079, from 10 April 1950, or "The Law of Impeachment", states that "The crimes defined in this law, even when simply attempted, are subject to the penalty of loss of office, with disqualification for up to five years for the exercise of any public function, to be imposed by the Federal Senate in proceedings against the President of the Republic, Ministers of State, Ministers of the Supreme Federal Tribunal, or the Attorney General."

Initiation: An accusation of a responsibility crime against the President may be brought by any Brazilian citizen however the President of the Chamber of Deputies holds prerogative to accept the charge, which if accepted will be read at the next session and reported to the President of the Republic.

Extraordinary Committee: An extraordinary committee is elected with member representation from each political party proportional to that party's membership. The President is then allowed ten parliamentary sessions for defense, which lead to two legislative sessions to form a rapporteur's legal opinion as to if impeachment proceedings will or will not be sent for a trial in the Senate. The rapporteur's opinion is voted on in the Committee; and on a simple majority it may be accepted. Failing that, the Committee adopts an opinion produced by the majority. For example, if the rapporteur's opinion is that no impeachment is warranted, and the Committee vote fails to accept it, then the Committee adopts the opinion to proceed with impeachment. Likewise, if the rapporteur's opinion is to proceed with impeachment, but it fails to achieve majority in the Committee, then the Committee adopts the opinion not to impeach. If the vote succeeds, then the rapporteur's opinion is adopted.

Chamber of Deputies: The Chamber issues a call-out vote to accept the opinion of the Committee, requiring a supermajority of two thirds in favor of an impeachment opinion (or a supermajority of two thirds against a dismissal opinion) of the Committee, in order to authorize the Senate impeachment proceedings. The President is suspended (provisionally removed) from office as soon as the Senate receives and accepts from the Chamber of Deputies the impeachment charges and decides to proceed with a trial.

The Senate: The process in the Senate had been historically lacking in procedural guidance until 1992, when the Senate published in the Official Diary of the Union the step-by-step procedure of the Senate's impeachment process, which involves the formation of another special committee and closely resembles the lower house process, with time constraints imposed on the steps taken. The committee's opinion must be presented within 10 days, after which it is put to a call-out vote at the next session. The vote must proceed within a single session; the vote on President Rousseff took over 20 hours. A simple majority vote in the Senate begins formal deliberation on the complaint, immediately suspends the President from office, installs the Vice President as acting president, and begins a 20-day period for written defense as well as up to 180-days for the trial. In the event the trial proceeds slowly and exceeds 180 days, the Brazilian Constitution determines that the President is entitled to return and stay provisionally in office until the trial comes to its decision.

Senate plenary deliberation: The committee interrogates the accused or their counsel, from which they have a right to abstain, and also a probative session which guarantees the accused rights to contradiction, or audiatur et altera pars, allowing access to the courts and due process of law under Article 5 of the constitution. The accused has 15 days to present written arguments in defense and answer to the evidence gathered, and then the committee shall issue an opinion on the merits within ten days. The entire package is published for each senator before a single plenary session issues a call-out vote, which shall proceed to trial on a simple majority and close the case otherwise.

Senate trial: A hearing for the complainant and the accused convenes within 48 hours of notification from deliberation, from which a trial is scheduled by the president of the Supreme Court no less than ten days after the hearing. The senators sit as judges, while witnesses are interrogated and cross-examined; all questions must be presented to the president of the Supreme Court, who, as prescribed in the Constitution, presides over the trial. The president of the Supreme Court allots time for debate and rebuttal, after which time the parties leave the chamber and the senators deliberate on the indictment. The President of the Supreme Court reads the summary of the grounds, the charges, the defense and the evidence to the Senate. The senators in turn issue their judgement. On conviction by a supermajority of two thirds, the president of the Supreme Court pronounces the sentence and the accused is immediately notified. If there is no supermajority for conviction, the accused is acquitted.

Upon conviction, the officeholder has his or her political rights revoked for eight years, which bars them from running for any office during that time.

Fernando Collor de Mello, the 32nd President of Brazil, resigned in 1992 amidst impeachment proceedings. Despite his resignation, the Senate nonetheless voted to convict him and bar him from holding any office for eight years, due to evidence of bribery and misappropriation.

In 2016, the Chamber of Deputies initiated an impeachment case against President Dilma Rousseff on allegations of budgetary mismanagement, a crime of responsibility under the Constitution. On 12 May 2016, after 20 hours of deliberation, the admissibility of the accusation was approved by the Senate with 55 votes in favor and 22 against (an absolute majority would have been sufficient for this step) and Vice President Michel Temer was notified to assume the duties of the President pending trial. On August 31, 61 senators voted in favor of impeachment and 20 voted against it, thus achieving the 2⁄3 majority needed for Rousseff's definitive removal. A vote to disqualify her for five years was taken and failed (in spite of the Constitution not separating disqualification from removal) having less than two thirds in favor.

Croatia

The process of impeaching the president of Croatia can be initiated by a two-thirds majority vote in favor in the Sabor and is thereafter referred to the Constitutional Court, which must accept such a proposal with a two-thirds majority vote in favor in order for the president to be removed from office. This has never occurred in the history of the Republic of Croatia. In case of a successful impeachment motion a president's constitutional term of five years would be terminated and an election called within 60 days of the vacancy occurring. During the period of vacancy the presidential powers and duties would be carried out by the speaker of the Croatian Parliament in his/her capacity as Acting President of the Republic.

Czech Republic

In 2013, the constitution was changed. Since 2013, the process can be started by at least three-fifths of present senators, and must be approved by at least three-fifths of all members of the Chamber of Deputies within three months. Also, the President can be impeached for high treason (newly defined in the Constitution) or any serious infringement of the Constitution.

The process starts in the Senate of the Czech Republic which has the right to only impeach the president. After the approval by the Chamber of Deputies, the case is passed to the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, which has to decide the verdict against the president. If the Court finds the President guilty, then the President is removed from office and is permanently barred from being elected President of the Czech Republic again.

No Czech president has ever been impeached, though members of the Senate sought to impeach President Václav Klaus in 2013. This case was dismissed by the court, which reasoned that his mandate had expired. The Senate also proposed to impeach president Miloš Zeman in 2019 but the Chamber of Deputies did not vote on the issue in time and thus the case did not even proceed to the Court.

Denmark

In Denmark the possibility for current and former ministers being impeached was established with the Danish Constitution of 1849. Unlike many other countries Denmark does not have a Constitutional Court who would normally handle these types of cases. Instead Denmark has a special Court of Impeachment (In Danish: Rigsretten) which is called upon every time a current and former minister have been impeached. The role of the Impeachment Court is to process and deliver judgments against current and former ministers who are accused of unlawful conduct in office. The legal content of ministerial responsibility is laid down in the Ministerial Accountability Act which has its background in section 13 of the Danish Constitution, according to which the ministers' accountability is determined in more detail by law. In Denmark the normal practice in terms of impeachment cases is that it needs to be brought up in the Danish Parliament (Folketing) first for debate between the different members and parties in the parliament. After the debate the members of the Danish Parliament vote on whether a current or former minister needs to be impeached. If there is a majority in the Danish Parliament for an impeachment case against a current or former minister, an Impeachment Court is called into session. In Denmark the Impeachment Court consists of up to 15 Supreme Court judges and 15 parliament members appointed by the Danish Parliament. The members of the Impeachment Court in Denmark serve a six-year term in this position.

In 1995 the former Minister of Justice Erik Ninn-Hansen from the Conservative People's Party was impeached in connection with the Tamil Case. The case was centered around the illegal processing of family reunification applications. From September 1987 to January 1989 applications for family reunification of Tamil refugees from civil war-torn Sri Lanka were put on hold in violation of Danish and International law. On 22 June 1995, Ninn-Hansen was found guilty of violating paragraph five subsection one of the Danish Ministerial Responsibility Act which says: A minister is punished if he intentionally or through gross negligence neglects the duties incumbent on him under the constitution or legislation in general or according to the nature of his post. A majority of the judges in that impeachment case voted for former Minister of Justice Erik Ninn-Hansen to receive a suspended sentence of four months with one year of probation. The reason why the sentence was made suspended was especially in relation to Ninn-Hansen's personal circumstances, in particular, his health and age - Ninn-Hansen was 73 years old when the sentence was handed down. After the verdict, Ninn-Hansen complained to the European Court of Human Rights and complained, among other things, that the Court of Impeachment was not impartial. The European Court of Human Rights dismissed the complaint on 18 May 1999. As a direct result and consequence of this case, the Conservative-led government and Prime Minister at that time Poul Schlüter was forced to step down from power.

In February 2021 the former Minister for Immigration and Integration Inger Støjberg at that time member of the Danish Liberal Party Venstre was impeached when it was discovered that she had possibly against both Danish and International law tried to separate couples in refugee centres in Denmark, as the wives of the couples were under legal age. According to a commission report Inger Støjberg had also lied in the Danish Parliament and failed to report relevant details to the Parliamentary Ombudsman The decision to initiate an impeachment case was adopted by the Danish Parliament with a 141–30 vote and decision (In Denmark 90 members of the parliament need to vote for impeachment before it can be implemented). On 13 December 2021 former Minister for Immigration and Integration Inger Støjberg was convicted by the special Court of Impeachment of separating asylum seeker families illegally according to Danish and international law and sentenced to 60 days in prison. The majority of the judges in the special Court of Impeachment (25 out of 26 judges) found that it had been proven that Inger Støjberg on 10 February 2016 decided that an accommodation scheme should apply without the possibility of exceptions, so that all asylum-seeking spouses and cohabiting couples where one was a minor aged 15–17, had to be separated and accommodated separately in separate asylum centers. On 21 December, a majority in the Folketing voted that the sentence means that she is no longer worthy of sitting in the Folketing and she therefore immediately lost her seat.

France

In France the comparable procedure is called destitution. The president of France can be impeached by the French Parliament for willfully violating the Constitution or the national laws. The process of impeachment is written in the 68th article of the French Constitution. A group of senators or a group of members of the National Assembly can begin the process. Then, both the National Assembly and the Senate must acknowledge the impeachment. After the upper and lower houses' agreement, they unite to form the High Court. Finally, the High Court must decide to declare the impeachment of the president of France—or not.

Germany

The federal president of Germany can be impeached both by the Bundestag and by the Bundesrat for willfully violating federal law. Once the Bundestag or the Bundesrat impeaches the president, the Federal Constitutional Court decides whether the President is guilty as charged and, if this is the case, whether to remove him or her from office. The Federal Constitutional Court also has the power to remove federal judges from office for willfully violating core principles of the federal constitution or a state constitution. The impeachment procedure is regulated in Article 61 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany.

There is no formal impeachment process for the chancellor of Germany, however the Bundestag can replace the chancellor at any time by voting for a new chancellor (constructive vote of no confidence, Article 67 of the Basic Law).

There has never been an impeachment against the President so far. Constructive votes of no confidence against the chancellor occurred in 1972 and 1982, with only the second one being successful.

Hong Kong

The chief executive of Hong Kong can be impeached by the Legislative Council. A motion for investigation, initiated jointly by at least one-fourth of all the legislators charging the Chief Executive with "serious breach of law or dereliction of duty" and refusing to resign, shall first be passed by the council. An independent investigation committee, chaired by the chief justice of the Court of Final Appeal, will then carry out the investigation and report back to the council. If the Council find the evidence sufficient to substantiate the charges, it may pass a motion of impeachment by a two-thirds majority.

However, the Legislative Council does not have the power to actually remove the chief executive from office, as the chief executive is appointed by the Central People's Government (State Council of China). The council can only report the result to the Central People's Government for its decision.

Hungary

Article 13 of Hungary's Fundamental Law (constitution) provides for the process of impeaching and removing the president. The president enjoys immunity from criminal prosecution while in office, but may be charged with crimes committed during his term afterwards. Should the president violate the constitution while discharging his duties or commit a willful criminal offense, he may be removed from office. Removal proceedings may be proposed by the concurring recommendation of one-fifth of the 199 members of the country's unicameral Parliament. Parliament votes on the proposal by secret ballot, and if two thirds of all representatives agree, the president is impeached. Once impeached, the president's powers are suspended, and the Constitutional Court decides whether or not the President should be removed from office.

India

The president and judges, including the chief justice of the supreme court and high courts, can be impeached by the parliament before the expiry of the term for violation of the Constitution. Other than impeachment, no other penalty can be given to a president in position for the violation of the Constitution under Article 361 of the constitution. However a president after his/her term/removal can be punished for his already proven unlawful activity under disrespecting the constitution, etc. No president has faced impeachment proceedings. Hence, the provisions for impeachment have never been tested. The sitting president cannot be charged and needs to step down in order for that to happen.

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland formal impeachment applies only to the Irish president. Article 12 of the Irish Constitution provides that, unless judged to be "permanently incapacitated" by the Supreme Court, the president can be removed from office only by the houses of the Oireachtas (parliament) and only for the commission of "stated misbehaviour". Either house of the Oireachtas may impeach the president, but only by a resolution approved by a majority of at least two thirds of its total number of members; and a house may not consider a proposal for impeachment unless requested to do so by at least thirty of its number.

Where one house impeaches the president, the remaining house either investigates the charge or commissions another body or committee to do so. The investigating house can remove the president if it decides, by at least a two-thirds majority of its members, both that the president is guilty of the charge and that the charge is sufficiently serious as to warrant the president's removal. To date no impeachment of an Irish president has ever taken place. The president holds a largely ceremonial office, the dignity of which is considered important, so it is likely that a president would resign from office long before undergoing formal conviction or impeachment.

Italy

In Italy, according to Article 90 of the Constitution, the President of Italy can be impeached through a majority vote of the Parliament in joint session for high treason and for attempting to overthrow the Constitution. If impeached, the president of the Republic is then tried by the Constitutional Court integrated with sixteen citizens older than forty chosen by lot from a list compiled by the Parliament every nine years.

Italian press and political forces made use of the term "impeachment" for the attempt by some members of parliamentary opposition to initiate the procedure provided for in Article 90 against Presidents Francesco Cossiga (1991), Giorgio Napolitano (2014) and Sergio Mattarella (2018).

Japan

By Article 78 of the Constitution of Japan, judges can be impeached. The voting method is specified by laws. The National Diet has two organs, namely 裁判官訴追委員会 (Saibankan sotsui iinkai) and 裁判官弾劾裁判所 (Saibankan dangai saibansho), which is established by Article 64 of the Constitution. The former has a role similar to prosecutor and the latter is analogous to Court. Seven judges were removed by them.

Liechtenstein

Members of the Liechtenstein Government can be impeached before the State Court for breaches of the Constitution or of other laws. As a hereditary monarchy the Sovereign Prince cannot be impeached as he "is not subject to the jurisdiction of the courts and does not have legal responsibility". The same is true of any member of the Princely House who exercises the function of head of state should the Prince be temporarily prevented or in preparation for the Succession.

Lithuania

In the Republic of Lithuania, the president may be impeached by a three-fifths majority in the Seimas. President Rolandas Paksas was removed from office by impeachment on 6 April 2004 after the Constitutional Court of Lithuania found him guilty of having violated his oath and the constitution. He was the first European head of state to have been impeached.

Norway

Members of government, representatives of the national assembly (Stortinget) and Supreme Court judges can be impeached for criminal offenses tied to their duties and committed in office, according to the Constitution of 1814, §§ 86 and 87. The procedural rules were modeled after the U.S. rules and are quite similar to them. Impeachment has been used eight times since 1814, last in 1927. Many argue that impeachment has fallen into desuetude. In cases of impeachment, an appointed court (Riksrett) takes effect.

Philippines

Impeachment in the Philippines follows procedures similar to the United States. Under Sections 2 and 3, Article XI, Constitution of the Philippines, the House of Representatives of the Philippines has the exclusive power to initiate all cases of impeachment against the president, vice president, members of the Supreme Court, members of the Constitutional Commissions (Commission on Elections, Civil Service Commission and the Commission on Audit), and the ombudsman. When a third of its membership has endorsed article(s) of impeachment, it is then transmitted to the Senate of the Philippines which tries and decide, as impeachment tribunal, the impeachment case.

A main difference from U.S. proceedings however is that only one third of House members are required to approve the motion to impeach the president (as opposed to a simple majority of those present and voting in their U.S. counterpart). In the Senate, selected members of the House of Representatives act as the prosecutors and the senators act as judges with the Senate president presiding over the proceedings (the chief justice jointly presides with the Senate president if the president is on trial). Like the United States, to convict the official in question requires that a minimum of two thirds (i.e. 16 of 24 members) of all the members of the Senate vote in favor of conviction. If an impeachment attempt is unsuccessful or the official is acquitted, no new cases can be filed against that impeachable official for at least one full year.

Impeachment proceedings and attempts

President Joseph Estrada was the first official impeached by the House in 2000, but the trial ended prematurely due to outrage over a vote to open an envelope where that motion was narrowly defeated by his allies. Estrada was deposed days later during the 2001 EDSA Revolution.

In 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008, impeachment complaints were filed against President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, but none of the cases reached the required endorsement of 1⁄3 of the members for transmittal to, and trial by, the Senate.

In March 2011, the House of Representatives impeached Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez, becoming the second person to be impeached. In April, Gutierrez resigned prior to the Senate's convening as an impeachment court.

In December 2011, in what was described as "blitzkrieg fashion", 188 of the 285 members of the House of Representatives voted to transmit the 56-page articles of impeachment against Supreme Court chief justice Renato Corona in his impeachment.

To date, three officials had been successfully impeached by the House of Representatives, and two were not convicted. The latter, Chief Justice Renato C. Corona, was convicted on 29 May 2012, by the Senate under Article II of the Articles of Impeachment (for betraying public trust), with 20–3 votes from the Senator Judges.

Peru

The first impeachment process against Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, then the incumbent President of Peru since 2016, was initiated by the Congress of Peru on 15 December 2017. According to Luis Galarreta, the President of the Congress, the whole process of impeachment could have taken as little as a week to complete. This event was part of the second stage of the political crisis generated by the confrontation between the Government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and the Congress, in which the opposition Popular Force has an absolute majority. The impeachment request was rejected by the congress on 21 December 2017, for failing to obtain sufficient votes for the deposition.

Romania

The president can be impeached by Parliament and is then suspended. A referendum then follows to determine whether the suspended President should be removed from office. President Traian Băsescu was impeached twice by the Parliament: in 2007 and then again in July 2012. A referendum was held on 19 May 2007 and a large majority of the electorate voted against removing the president from office. For the most recent suspension a referendum was held on July 29, 2012; the results were heavily against the president, but the referendum was invalidated due to low turnout.

Russia

In 1999, members of the State Duma of Russia, led by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, unsuccessfully attempted to impeach President Boris Yeltsin on charges relating to his role in the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis and launching the First Chechen War (1995–96); efforts to launch impeachment proceedings failed.

Singapore

The Constitution of Singapore allows the impeachment of a sitting president on charges of treason, violation of the Constitution, corruption, or attempting to mislead the Presidential Elections Committee for the purpose of demonstrating eligibility to be elected as president. The prime minister or at least one-quarter of all members of Parliament (MPs) can pass an impeachment motion, which can succeed only if at least half of all MPs (excluding nominated members) vote in favor, whereupon the chief justice of the Supreme Court will appoint a tribunal to investigate allegations against the president. If the tribunal finds the president guilty, or otherwise declares that the president is "permanently incapable of discharging the functions of his office by reason of mental or physical infirmity", Parliament will hold a vote on a resolution to remove the president from office, which requires a three-quarters majority to succeed. No president has ever been removed from office in this fashion.

South Africa

When the Union of South Africa was established in 1910, the only officials who could be impeached (though the term itself was not used) were the chief justice and judges of the Supreme Court of South Africa. The scope was broadened when the country became a republic in 1961, to include the state president. It was further broadened in 1981 to include the new office of vice state president; and in 1994 to include the executive deputy presidents, the public protector and the Auditor-General. Since 1997, members of certain commissions established by the Constitution can also be impeached. The grounds for impeachment, and the procedures to be followed, have changed several times over the years.

South Korea

According to the Article 65(1) of Constitution of South Korea, President, Prime Minister, members of the State Council, heads of Executive Ministries, Justices of the Constitutional Court, judges, members of the National Election Commission, the Chairperson and members of the Board of Audit and Inspection can be impeached by the National Assembly when they violated the Constitution or other statutory duties. By article 65(2) of the Constitution, proposal of impeachment needs simple majority of votes among quorum of one-thirds of the National Assembly. However, exceptionally, impeachment on President of South Korea needs simple majority of votes among quorum of two-thirds of the National Assembly. When impeachment proposal is passed in the National Assembly, it is finally reviewed under jurisdiction the Constitutional Court of Korea, according to article 111(1) of the Constitution. During review of impeachment in the Constitutional Court, the impeached is suspended from exercising power by article 65(3) of the Constitution.

Two presidents have been impeached since the establishing of the Republic of Korea in 1948. Roh Moo-hyun in 2004 was impeached by the National Assembly but was overturned by the Constitutional Court. Park Geun-hye in 2016 was impeached by the National Assembly, and the impeachment was confirmed by the Constitutional Court on March 10, 2017.

In February 2021, Judge Lim Seong-geun of the Busan High Court was impeached by the National Assembly for meddling in politically sensitive trials, the first ever impeachment of a judge in Korean history. Unlike presidential impeachments, only a simple majority is required to impeach. Judge Lim's term expired before the Constitutional Court could render a verdict, leading the court to dismiss the case.

Turkey

In Turkey, according to the Constitution, the Grand National Assembly may initiate an investigation of the president, the vice president or any member of the Cabinet upon the proposal of simple majority of its total members, and within a period less than a month, the approval of three-fifths of the total members. The investigation would be carried out by a commission of fifteen members of the Assembly, each nominated by the political parties in proportion to their representation therein. The commission would submit its report indicating the outcome of the investigation to the speaker within two months. If the investigation is not completed within this period, the commission's time may be renewed for another month. Within ten days of its submission to the speaker, the report would be distributed to all members of the Assembly, and ten days after its distribution, the report would be discussed on the floor. Upon the approval of two thirds of the total number of the Assembly by secret vote, the person or persons, about whom the investigation was conducted, may be tried before the Constitutional Court. The trial would be finalized within three months, and if not, a one-time additional period of three months shall be granted. The president, about whom an investigation has been initiated, may not call for an election. The president, who is convicted by the Court, would be removed from office.

The provision of this article shall also apply to the offenses for which the president allegedly worked during his term of office.

Ukraine

During the crisis which started in November 2013, the increasing political stress of the face-down between the protestors occupying Independence Square in Kyiv and the State Security forces under the control of President Yanukovych led to deadly armed force being used on the protestors. Following the negotiated return of Kyiv's City Hall on 16 February 2014, occupied by the protesters since November 2013, the security forces thought they could also retake "Maidan", Independence Square. The ensuing fighting from 17 through 21 February 2014 resulted in a considerable number of deaths and a more generalised alienation of the population, and the withdrawal of President Yanukovych to his support area in the East of Ukraine.

In the wake of the president's departure, Parliament convened on 22 February; it reinstated the 2004 Constitution, which reduced presidential authority, and voted impeachment of President Yanukovych as de facto recognition of his departure from office as President of an integrated Ukraine. The president riposted that Parliament's acts were illegal as they could pass into law only by presidential signature.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, in principle, anybody may be prosecuted and tried by the two Houses of Parliament for any crime. The first recorded impeachment is that of William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer during the Good Parliament of 1376. The latest was that of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville which started in 1805 and which ended with his acquittal in June 1806. Over the centuries, the procedure has been supplemented by other forms of oversight including select committees, confidence motions, and judicial review, while the privilege of peers to trial only in the House of Lords was abolished in 1948 (see Judicial functions of the House of Lords § Trials), and thus impeachment, which has not kept up with modern norms of democracy or procedural fairness, is generally considered obsolete.

United States

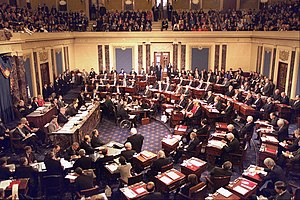

In the federal system, the Article One of the United States Constitution provides that the House of Representatives has the "sole Power of Impeachment" and the Senate has "the sole Power to try all Impeachments". Article Two provides that "The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." In the United States, impeachment is the first of two stages; an official may be impeached by a majority vote of the House, but conviction and removal from office in the Senate requires "the concurrence of two thirds of the members present". Impeachment is analogous to an indictment.

According to the House practice manual, "Impeachment is a constitutional remedy to address serious offenses against the system of government. It is the first step in a remedial process—that of removal from public office and possible disqualification from holding further office. The purpose of impeachment is not punishment; rather, its function is primarily to maintain constitutional government." Impeachment may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements. The Constitution provides that "Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law." It is generally accepted that "a former President may be prosecuted for crimes of which he was acquitted by the Senate".

The U.S. House of Representatives has impeached an official 21 times since 1789: four times for presidents, 15 times for federal judges, once for a Cabinet secretary, and once for a senator. Of the 21, the Senate voted to remove 8 (all federal judges) from office. The four impeachments of presidents were: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and again in 2021. All four impeachments were followed by acquittal in the Senate. An impeachment process was also commenced against Richard Nixon, but he resigned in 1974 to avoid likely removal from office.

Almost all state constitutions set forth parallel impeachment procedures for state governments, allowing the state legislature to impeach officials of the state government. From 1789 through 2008, 14 governors have been impeached (including two who were impeached twice), of whom seven governors were convicted.