In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

Description

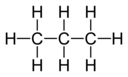

The combining capacity, or affinity of an atom of a given element is determined by the number of hydrogen atoms that it combines with. In methane, carbon has a valence of 4; in ammonia, nitrogen has a valence of 3; in water, oxygen has a valence of 2; and in hydrogen chloride, chlorine has a valence of 1. Chlorine, as it has a valence of one, can be substituted for hydrogen. Phosphorus has a valence of 5 in phosphorus pentachloride, PCl5. Valence diagrams of a compound represent the connectivity of the elements, with lines drawn between two elements, sometimes called bonds, representing a saturated valency for each element. The two tables below show some examples of different compounds, their valence diagrams, and the valences for each element of the compound.

| Compound | H2 Hydrogen |

CH4 Methane |

C3H8 Propane |

C2H2 Acetylene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

||

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

| Compound | NH3 Ammonia |

NaCN Sodium cyanide |

H2S Hydrogen sulfide |

H2SO4 Sulfuric acid |

Cl2O7 Dichlorine heptoxide |

XeO4 Xenon tetroxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagram |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Valencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modern definitions

Valence is defined by the IUPAC as:

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.

An alternative modern description is:

- The number of hydrogen atoms that can combine with an element in a binary hydride or twice the number of oxygen atoms combining with an element in its oxide or oxides.

This definition differs from the IUPAC definition as an element can be said to have more than one valence.

A very similar modern definition given in a recent article defines the valence of a particular atom in a molecule as "the number of electrons that an atom uses in bonding", with two equivalent formulas for calculating valence:

- valence = number of electrons in valence shell of free atom – number of non-bonding electrons on atom in molecule,

and

- valence = number of bonds + formal charge.

Historical development

The etymology of the words valence (plural valences) and valency (plural valencies) traces back to 1425, meaning "extract, preparation", from Latin valentia "strength, capacity", from the earlier valor "worth, value", and the chemical meaning referring to the "combining power of an element" is recorded from 1884, from German Valenz.

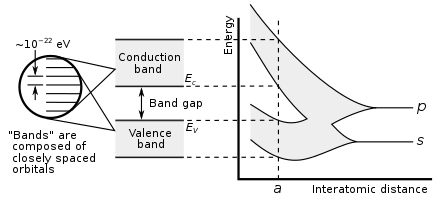

The concept of valence was developed in the second half of the 19th century and helped successfully explain the molecular structure of inorganic and organic compounds. The quest for the underlying causes of valence led to the modern theories of chemical bonding, including the cubical atom (1902), Lewis structures (1916), valence bond theory (1927), molecular orbitals (1928), valence shell electron pair repulsion theory (1958), and all of the advanced methods of quantum chemistry.

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of "ultimate" particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds. If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and likewise for the other combinations of ultimate particles (see illustration).

The exact inception, however, of the theory of chemical valencies can be traced to an 1852 paper by Edward Frankland, in which he combined the older radical theory with thoughts on chemical affinity to show that certain elements have the tendency to combine with other elements to form compounds containing 3, i.e., in the 3-atom groups (e.g., NO3, NH3, NI3, etc.) or 5, i.e., in the 5-atom groups (e.g., NO5, NH4O, PO5, etc.), equivalents of the attached elements. According to him, this is the manner in which their affinities are best satisfied, and by following these examples and postulates, he declares how obvious it is that

A tendency or law prevails (here), and that, no matter what the characters of the uniting atoms may be, the combining power of the attracting element, if I may be allowed the term, is always satisfied by the same number of these atoms.

This “combining power” was afterwards called quantivalence or valency (and valence by American chemists). In 1857 August Kekulé proposed fixed valences for many elements, such as 4 for carbon, and used them to propose structural formulas for many organic molecules, which are still accepted today.

Most 19th-century chemists defined the valence of an element as the number of its bonds without distinguishing different types of valence or of bond. However, in 1893 Alfred Werner described transition metal coordination complexes such as [Co(NH3)6]Cl3, in which he distinguished principal and subsidiary valences (German: 'Hauptvalenz' and 'Nebenvalenz'), corresponding to the modern concepts of oxidation state and coordination number respectively.

For main-group elements, in 1904 Richard Abegg considered positive and negative valences (maximal and minimal oxidation states), and proposed Abegg's rule to the effect that their difference is often 8.

Electrons and valence

The Rutherford model of the nuclear atom (1911) showed that the exterior of an atom is occupied by electrons, which suggests that electrons are responsible for the interaction of atoms and the formation of chemical bonds. In 1916, Gilbert N. Lewis explained valence and chemical bonding in terms of a tendency of (main-group) atoms to achieve a stable octet of 8 valence-shell electrons. According to Lewis, covalent bonding leads to octets by the sharing of electrons, and ionic bonding leads to octets by the transfer of electrons from one atom to the other. The term covalence is attributed to Irving Langmuir, who stated in 1919 that "the number of pairs of electrons which any given atom shares with the adjacent atoms is called the covalence of that atom". The prefix co- means "together", so that a co-valent bond means that the atoms share a valence. Subsequent to that, it is now more common to speak of covalent bonds rather than valence, which has fallen out of use in higher-level work from the advances in the theory of chemical bonding, but it is still widely used in elementary studies, where it provides a heuristic introduction to the subject.

In the 1930s, Linus Pauling proposed that there are also polar covalent bonds, which are intermediate between covalent and ionic, and that the degree of ionic character depends on the difference of electronegativity of the two bonded atoms.

Pauling also considered hypervalent molecules, in which main-group elements have apparent valences greater than the maximal of 4 allowed by the octet rule. For example, in the sulfur hexafluoride molecule (SF6), Pauling considered that the sulfur forms 6 true two-electron bonds using sp3d2 hybrid atomic orbitals, which combine one s, three p and two d orbitals. However more recently, quantum-mechanical calculations on this and similar molecules have shown that the role of d orbitals in the bonding is minimal, and that the SF6 molecule should be described as having 6 polar covalent (partly ionic) bonds made from only four orbitals on sulfur (one s and three p) in accordance with the octet rule, together with six orbitals on the fluorines. Similar calculations on transition-metal molecules show that the role of p orbitals is minor, so that one s and five d orbitals on the metal are sufficient to describe the bonding.

Common valences

For elements in the main groups of the periodic table, the valence can vary between 1 and 7.

| Group | Valence 1 | Valence 2 | Valence 3 | Valence 4 | Valence 5 | Valence 6 | Valence 7 | Valence 8 | Typical valences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (I) | NaCl | 1 | |||||||

| 2 (II) | MgCl2 | 2 | |||||||

| 13 (III) | BCl3 AlCl3 Al2O3 |

3 | |||||||

| 14 (IV) | CO | CH4 | 4 | ||||||

| 15 (V) | NO | NH3 PH3 As2O3 |

NO2 | N2O5 PCl5 |

3 and 5 | ||||

| 16 (VI) | H2O H2S |

SO2 | SO3 | 2 and 6 | |||||

| 17 (VII) | HCl | HClO2 | ClO2 | HClO3 | Cl2O7 | 1 and 7 | |||

| 18 (VIII) |

|

|

XeO4 | 8 |

Many elements have a common valence related to their position in the periodic table, and nowadays this is rationalised by the octet rule. The Greek/Latin numeral prefixes (mono-/uni-, di-/bi-, tri-/ter-, and so on) are used to describe ions in the charge states 1, 2, 3, and so on, respectively. Polyvalence or multivalence refers to species that are not restricted to a specific number of valence bonds. Species with a single charge are univalent (monovalent). For example, the Cs+ cation is a univalent or monovalent cation, whereas the Ca2+ cation is a divalent cation, and the Fe3+ cation is a trivalent cation. Unlike Cs and Ca, Fe can also exist in other charge states, notably 2+ and 4+, and is thus known as a multivalent (polyvalent) ion. Transition metals and metals to the right are typically multivalent but there is no simple pattern predicting their valency.

| Valence | More common adjective‡ | Less common synonymous adjective‡§ |

|---|---|---|

| 0-valent | zerovalent | nonvalent |

| 1-valent | monovalent | univalent |

| 2-valent | divalent | bivalent |

| 3-valent | trivalent | tervalent |

| 4-valent | tetravalent | quadrivalent |

| 5-valent | pentavalent | quinquevalent / quinquivalent |

| 6-valent | hexavalent | sexivalent |

| 7-valent | heptavalent | septivalent |

| 8-valent | octavalent | — |

| 9-valent | nonavalent | — |

| 10-valent | decavalent | — |

| multiple / many / variable | polyvalent | multivalent |

| together | covalent | — |

| not together | noncovalent | — |

† The same adjectives are also used in medicine to refer to vaccine valence, with the slight difference that in the latter sense, quadri- is more common than tetra-.

‡ As demonstrated by hit counts in Google web search and Google Books search corpora (accessed 2017).

§ A few other forms can be found in large English-language corpora (for example, *quintavalent, *quintivalent, *decivalent), but they are not the conventionally established forms in English and thus are not entered in major dictionaries.

Valence versus oxidation state

Because of the ambiguity of the term valence, other notations are currently preferred. Beside the system of oxidation states (also called oxidation numbers) as used in Stock nomenclature for coordination compounds, and the lambda notation, as used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, oxidation state is a more clear indication of the electronic state of atoms in a molecule.

The oxidation state of an atom in a molecule gives the number of valence electrons it has gained or lost. In contrast to the valency number, the oxidation state can be positive (for an electropositive atom) or negative (for an electronegative atom).

Elements in a high oxidation state can have a valence higher than four. For example, in perchlorates, chlorine has seven valence bonds; ruthenium, in the +8 oxidation state in ruthenium tetroxide, has eight valence bonds.

Examples

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen chloride | HCl | H = 1 Cl = 1 | H = +1 Cl = −1 |

| Perchloric acid * | HClO4 | H = 1 Cl = 7 O = 2 | H = +1 Cl = +7 O = −2 |

| Sodium hydride | NaH | Na = 1 H = 1 | Na = +1 H = −1 |

| Ferrous oxide ** | FeO | Fe = 2 O = 2 | Fe = +2 O = −2 |

| Ferric oxide ** | Fe2O3 | Fe = 3 O = 2 | Fe = +3 O = −2 |

* The univalent perchlorate ion (ClO−

4) has valence 1.

** Iron oxide appears in a crystal structure, so no typical molecule can be identified.

In ferrous oxide, Fe has oxidation state II; in ferric oxide, oxidation state III.

| Compound | Formula | Valence | Oxidation state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine | Cl2 | Cl = 1 | Cl = 0 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H2O2 | H = 1 O = 2 | H = +1 O = −1 |

| Acetylene | C2H2 | C = 4 H = 1 | C = −1 H = +1 |

| Mercury(I) chloride | Hg2Cl2 | Hg = 2 Cl = 1 | Hg = +1 Cl = −1 |

Valences may also be different from absolute values of oxidation states due to different polarity of bonds. For example, in dichloromethane, CH2Cl2, carbon has valence 4 but oxidation state 0.

"Maximum number of bonds" definition

Frankland took the view that the valence (he used the term "atomicity") of an element was a single value that corresponded to the maximum value observed. The number of unused valencies on atoms of what are now called the p-block elements is generally even, and Frankland suggested that the unused valencies saturated one another. For example, nitrogen has a maximum valence of 5, in forming ammonia two valencies are left unattached; sulfur has a maximum valence of 6, in forming hydrogen sulphide four valencies are left unattached.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has made several attempts to arrive at an unambiguous definition of valence. The current version, adopted in 1994:

- The maximum number of univalent atoms (originally hydrogen or chlorine atoms) that may combine with an atom of the element under consideration, or with a fragment, or for which an atom of this element can be substituted.

Hydrogen and chlorine were originally used as examples of univalent atoms, because of their nature to form only one single bond. Hydrogen has only one valence electron and can form only one bond with an atom that has an incomplete outer shell. Chlorine has seven valence electrons and can form only one bond with an atom that donates a valence electron to complete chlorine's outer shell. However, chlorine can also have oxidation states from +1 to +7 and can form more than one bond by donating valence electrons.

Hydrogen has only one valence electron, but it can form bonds with more than one atom. In the bifluoride ion ([HF

2]−

), for example, it forms a three-center four-electron bond with two fluoride atoms:

- [ F–H F– ↔ F– H–F ]

Another example is the Three-center two-electron bond in diborane (B2H6).