False-color Cassini radar mosaic of Titan's north polar region; the blue areas are lakes of liquid hydrocarbons

"The existence of lakes of liquid hydrocarbons on Titan opens up the possibility for solvents and energy sources that are alternatives to those in our biosphere and that might support novel life forms altogether different from those on Earth."—NASA Astrobiology Roadmap 2008[1]

Hypothetical types of biochemistry are forms of biochemistry speculated to be scientifically viable but not proven to exist at this time.[2] The kinds of living organisms currently known on Earth all use carbon compounds for basic structural and metabolic functions, water as a solvent, and DNA or RNA to define and control their form. If life exists on other planets or moons, it may be chemically similar; it is also possible that there are organisms with quite different chemistries[3]—for instance involving other classes of carbon compounds, compounds of another element, or another solvent in place of water.

The possibility of life-forms being based on "alternative" biochemistries is the topic of an ongoing scientific discussion, informed by what is known about extraterrestrial environments and about the chemical behaviour of various elements and compounds. It is also a common subject in science fiction.

The element silicon has been much discussed as a hypothetical alternative to carbon. Silicon is in the same group as carbon on the periodic table and, like carbon, it is tetravalent, although the silicon analogs of organic compounds are generally less stable. Hypothetical alternatives to water include ammonia, which, like water, is a polar molecule, and cosmically abundant; and non-polar hydrocarbon solvents such as methane and ethane, which are known to exist in liquid form on the surface of Titan.

Shadow biosphere

The Arecibo message (1974) sent information into space about basic chemistry of Earth life.

A shadow biosphere is a hypothetical microbial biosphere of Earth that uses radically different biochemical and molecular processes than currently known life.[4][5] Although life on Earth is relatively well-studied, the shadow biosphere may still remain unnoticed because the exploration of the microbial world targets primarily the biochemistry of the macro-organisms.

Alternative-chirality biomolecules

Perhaps the least unusual alternative biochemistry would be one with differing chirality of its biomolecules. In known Earth-based life, amino acids are almost universally of the L form and sugars are of the D form. Molecules of opposite chirality have identical chemical properties to their mirrored forms, so life that used D amino acids or L sugars may be possible; molecules of such a chirality, however, would be incompatible with organisms using the opposing chirality molecules. Amino acids whose chirality is opposite to the norm are found on Earth, and these substances are generally thought to result from decay of organisms of normal chirality. However, physicist Paul Davies speculates that some of them might be products of "anti-chiral" life.[6]It is questionable, however, whether such a biochemistry would be truly alien. Although it would certainly be an alternative stereochemistry, molecules that are overwhelmingly found in one enantiomer throughout the vast majority of organisms can nonetheless often be found in another enantiomer in different (often basal) organisms such as in comparisons between members of Archaea and other domains,[citation needed] making it an open topic whether an alternative stereochemistry is truly novel.

Non-carbon-based biochemistries

On Earth, all known living things have a carbon-based structure and system. Scientists have speculated about the pros and cons of using atoms other than carbon to form the molecular structures necessary for life, but no one has proposed a theory employing such atoms to form all the necessary structures. However, as Carl Sagan argued, it is very difficult to be certain whether a statement that applies to all life on Earth will turn out to apply to all life throughout the universe.[7] Sagan used the term "carbon chauvinism" for such an assumption.[8] He regarded silicon and germanium as conceivable alternatives to carbon;[8] but, on the other hand, he noted that carbon does seem more chemically versatile and is more abundant in the cosmos.[9]Silicon biochemistry

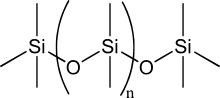

Structure of the silicone polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS).

Marine diatoms—carbon-based

organisms that extract silicon from sea water, in the form of its oxide

(silica) and incorporate it into their cell walls

The silicon atom has been much discussed as the basis for an alternative biochemical system, because silicon has many chemical properties similar to those of carbon and is in the same group of the periodic table, the carbon group. Like carbon, silicon can create molecules that are sufficiently large to carry biological information.[10]

However, silicon has several drawbacks as an alternative to carbon. Silicon, unlike carbon, lacks the ability to form chemical bonds with diverse types of atoms as is necessary for the chemical versatility required for metabolism. Elements creating organic functional groups with carbon include hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, and metals such as iron, magnesium, and zinc. Silicon, on the other hand, interacts with very few other types of atoms.[10] Moreover, where it does interact with other atoms, silicon creates molecules that have been described as "monotonous compared with the combinatorial universe of organic macromolecules".[10] This is because silicon atoms are much bigger, having a larger mass and atomic radius, and so have difficulty forming double bonds (the double bonded carbon is part of the carbonyl group, a fundamental motif of bio-organic chemistry).

Silanes, which are chemical compounds of hydrogen and silicon that are analogous to the alkane hydrocarbons, are highly reactive with water, and long-chain silanes spontaneously decompose. Molecules incorporating polymers of alternating silicon and oxygen atoms instead of direct bonds between silicon, known collectively as silicones, are much more stable. It has been suggested that silicone-based chemicals would be more stable than equivalent hydrocarbons in a sulfuric-acid-rich environment, as is found in some extraterrestrial locations.[11]

Of the varieties of molecules identified in the interstellar medium as of 1998, 84 are based on carbon while only 8 are based on silicon.[12] Moreover, of those 8 compounds, four also include carbon within them. The cosmic abundance of carbon to silicon is roughly 10 to 1. This may suggest a greater variety of complex carbon compounds throughout the cosmos, providing less of a foundation on which to build silicon-based biologies, at least under the conditions prevalent on the surface of planets. Also, even though Earth and other terrestrial planets are exceptionally silicon-rich and carbon-poor (the relative abundance of silicon to carbon in Earth's crust is roughly 925:1), terrestrial life is carbon-based. The fact that carbon is used instead of silicon, may be evidence that silicon is poorly suited for biochemistry on Earth-like planets. Reasons for which may be that silicon is less versatile than carbon in forming compounds, that the compounds formed by silicon are unstable, and that it blocks the flow of heat.[13]

Even so, biogenic silica is used by some Earth life, such as the silicate skeletal structure of diatoms. According to the clay hypothesis of A. G. Cairns-Smith, silicate minerals in water played a crucial role in abiogenesis: they replicated their crystal structures, interacted with carbon compounds, and were the precursors of carbon-based life.[14][15]

Although not observed in nature, carbon–silicon bonds have been added to biochemistry by using directed evolution (artificial selection). A heme containing cytochrome c protein from Rhodothermus marinus has been engineered using directed evolution to catalyze the formation of new carbon–silicon bonds between hydrosilanes and diazo compounds.[16]

Silicon compounds may possibly be biologically useful under temperatures or pressures different from the surface of a terrestrial planet, either in conjunction with or in a role less directly analogous to carbon. Polysilanols, the silicon compounds corresponding to sugars, are soluble in liquid nitrogen, suggesting that they could play a role in very low temperature biochemistry.[17][18]

In cinematic and literary science fiction, at a moment when man-made machines cross from nonliving to living, it is often posited, this new form would be the first example of non-carbon-based life. Since the advent of the microprocessor in the late 1960s, these machines are often classed as computers (or computer-guided robots) and filed under "silicon-based life", even though the silicon backing matrix of these processors is not nearly as fundamental to their operation as carbon is for "wet life".

Other exotic element-based biochemistries

- Boranes are dangerously explosive in Earth's atmosphere, but would be more stable in a reducing environment. However, boron's low cosmic abundance makes it less likely as a base for life than carbon.

- Various metals, together with oxygen, can form very complex and thermally stable structures rivaling those of organic compounds;[citation needed] the heteropoly acids are one such family. Some metal oxides are also similar to carbon in their ability to form both nanotube structures and diamond-like crystals (such as cubic zirconia). Titanium, aluminium, magnesium, and iron are all more abundant in the Earth's crust than carbon. Metal-oxide-based life could therefore be a possibility under certain conditions, including those (such as high temperatures) at which carbon-based life would be unlikely. The Cronin group at Glasgow University reported self-assembly of tungsten polyoxometalates into cell-like spheres.[19] By modifying their metal oxide content, the spheres can acquire holes that act as porous membrane, selectively allowing chemicals in and out of the sphere according to size.[19]

- Sulfur is also able to form long-chain molecules, but suffers from the same high-reactivity problems as phosphorus and silanes. The biological use of sulfur as an alternative to carbon is purely hypothetical, especially because sulfur usually forms only linear chains rather than branched ones. (The biological use of sulfur as an electron acceptor is widespread and can be traced back 3.5 billion years on Earth, thus predating the use of molecular oxygen.[20] Sulfur-reducing bacteria can utilize elemental sulfur instead of oxygen, reducing sulfur to hydrogen sulfide.)

Arsenic as an alternative to phosphorus

Arsenic, which is chemically similar to phosphorus, while poisonous for most life forms on Earth, is incorporated into the biochemistry of some organisms.[21] Some marine algae incorporate arsenic into complex organic molecules such as arsenosugars and arsenobetaines. Fungi and bacteria can produce volatile methylated arsenic compounds. Arsenate reduction and arsenite oxidation have been observed in microbes (Chrysiogenes arsenatis).[22] Additionally, some prokaryotes can use arsenate as a terminal electron acceptor during anaerobic growth and some can utilize arsenite as an electron donor to generate energy.It has been speculated that the earliest life forms on Earth may have used arsenic in place of phosphorus in the structure of their DNA.[23] A common objection to this scenario is that arsenate esters are so much less stable to hydrolysis than corresponding phosphate esters that arsenic is poorly suited for this function.[24]

The authors of a 2010 geomicrobiology study, supported in part by NASA, have postulated that a bacterium, named GFAJ-1, collected in the sediments of Mono Lake in eastern California, can employ such 'arsenic DNA' when cultured without phosphorus.[25][26] They proposed that the bacterium may employ high levels of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate or other means to reduce the effective concentration of water and stabilize its arsenate esters.[26] This claim was heavily criticized almost immediately after publication for the perceived lack of appropriate controls.[27][28] Science writer Carl Zimmer contacted several scientists for an assessment: "I reached out to a dozen experts ... Almost unanimously, they think the NASA scientists have failed to make their case".[29] Other authors were unable to reproduce their results and showed that the study had issues with phosphate contamination, suggesting that the low amounts present could sustain extremophile lifeforms.[30] Alternatively, it was suggested that GFAJ-1 cells grow by recycling phosphate from degraded ribosomes, rather than by replacing it with arsenate.[31]

Non-water solvents

Carl Sagan speculated alien life might use ammonia, hydrocarbons or hydrogen fluoride instead of water.

In addition to carbon compounds, all currently known terrestrial life also requires water as a solvent. This has led to discussions about whether water is the only liquid capable of filling that role. The idea that an extraterrestrial life-form might be based on a solvent other than water has been taken seriously in recent scientific literature by the biochemist Steven Benner,[32] and by the astrobiological committee chaired by John A. Baross.[33] Solvents discussed by the Baross committee include ammonia,[34] sulfuric acid,[35] formamide,[36] hydrocarbons,[36] and (at temperatures much lower than Earth's) liquid nitrogen, or hydrogen in the form of a supercritical fluid.[37]

Carl Sagan once described himself as both a carbon chauvinist and a water chauvinist;[38] however on another occasion he said he was a carbon chauvinist but "not that much of a water chauvinist".[39] He speculated on hydrocarbons,[39]:11 hydrofluoric acid,[40] and ammonia[39][40] as possible alternatives to water.

Some of the properties of water that are important for life processes include a large temperature range over which it is liquid, a high heat capacity (useful for temperature regulation), a large heat of vaporization, and the ability to dissolve a wide variety of compounds. Water is also amphoteric, meaning it can donate and accept an H+ ion, allowing it to act as an acid or a base. This property is crucial in many organic and biochemical reactions, where water serves as a solvent, a reactant, or a product. There are other chemicals with similar properties that have sometimes been proposed as alternatives. Additionally, water has the unusual property of being less dense as a solid (ice) than as a liquid. This is why bodies of water freeze over but do not freeze solid (from the bottom up). If ice were denser than liquid water (as is true for nearly all other compounds), then large bodies of liquid would slowly freeze solid, which would not be conducive to the formation of life. Water as a compound is cosmically abundant, although much of it is in the form of vapour or ice. Subsurface liquid water is considered likely or possible on several of the outer moons: Enceladus (where geysers have been observed), Europa, Titan, and Ganymede. Earth and Titan are the only worlds currently known to have stable bodies of liquid on their surfaces.

Not all properties of water are necessarily advantageous for life, however.[41] For instance, water ice has a high albedo,[41] meaning that it reflects a significant quantity of light and heat from the Sun. During ice ages, as reflective ice builds up over the surface of the water, the effects of global cooling are increased.[41]

There are some properties that make certain compounds and elements much more favorable than others as solvents in a successful biosphere. The solvent must be able to exist in liquid equilibrium over a range of temperatures the planetary object would normally encounter. Because boiling points vary with the pressure, the question tends not to be does the prospective solvent remain liquid, but at what pressure. For example, hydrogen cyanide has a narrow liquid phase temperature range at 1 atmosphere, but in an atmosphere with the pressure of Venus, with 92 bars (91 atm) of pressure, it can indeed exist in liquid form over a wide temperature range.

Ammonia

Artist's conception of how a planet with ammonia-based life might look.

The ammonia molecule (NH3), like the water molecule, is abundant in the universe, being a compound of hydrogen (the simplest and most common element) with another very common element, nitrogen.[42] The possible role of liquid ammonia as an alternative solvent for life is an idea that goes back at least to 1954, when J.B.S. Haldane raised the topic at a symposium about life's origin.[43]

Numerous chemical reactions are possible in an ammonia solution, and liquid ammonia has chemical similarities with water.[42][44] Ammonia can dissolve most organic molecules at least as well as water does and, in addition, it is capable of dissolving many elemental metals. Haldane made the point that various common water-related organic compounds have ammonia-related analogs; for instance the ammonia-related amine group (-NH2) is analogous to the water-related hydroxyl group (-OH).[44]

Ammonia, like water, can either accept or donate an H+ ion. When ammonia accepts an H+, it forms the ammonium cation (NH4+), analogous to hydronium (H3O+). When it donates an H+ ion, it forms the amide anion (NH2−), analogous to the hydroxide anion (OH−).[34] Compared to water, however, ammonia is more inclined to accept an H+ ion, and less inclined to donate one; it is a stronger nucleophile.[34] Ammonia added to water functions as Arrhenius base: it increases the concentration of the anion hydroxide. Conversely, using a solvent system definition of acidity and basicity, water added to liquid ammonia functions as an acid, because it increases the concentration of the cation ammonium.[44] The carbonyl group (C=O), which is much used in terrestrial biochemistry, would not be stable in ammonia solution, but the analogous imine group (C=NH) could be used instead.[34]

However, ammonia has some problems as a basis for life. The hydrogen bonds between ammonia molecules are weaker than those in water, causing ammonia's heat of vaporization to be half that of water, its surface tension to be a third, and reducing its ability to concentrate non-polar molecules through a hydrophobic effect. Gerald Feinberg and Robert Shapiro have questioned whether ammonia could hold prebiotic molecules together well enough to allow the emergence of a self-reproducing system.[45] Ammonia is also flammable in oxygen, and could not exist sustainably in an environment suitable for aerobic metabolism.[46]

Titan's theorized internal structure, subsurface ocean shown blue.

A biosphere based on ammonia would likely exist at temperatures or air pressures that are extremely unusual in relation to life on Earth. Life on Earth usually exists within the melting point and boiling point of water at normal pressure, between 0 °C (273 K) and 100 °C (373 K); at normal pressure ammonia's melting and boiling points are between −78 °C (195 K) and −33 °C (240 K). Chemical reactions generally proceed more slowly at a lower temperature. Therefore, ammonia-based life, if it exists, might metabolize more slowly and evolve more slowly than life on Earth.[46] On the other hand, lower temperatures could also enable living systems to use chemical species that would be too unstable at Earth temperatures to be useful.[42]

Ammonia could be a liquid at Earth-like temperatures, but at much higher pressures; for example, at 60 atm, ammonia melts at −77 °C (196 K) and boils at 98 °C (371 K).[34]

Ammonia and ammonia–water mixtures remain liquid at temperatures far below the freezing point of pure water, so such biochemistries might be well suited to planets and moons orbiting outside the water-based habitability zone. Such conditions could exist, for example, under the surface of Saturn's largest moon Titan.[47]

Methane and other hydrocarbons

Methane (CH4) is a simple hydrocarbon: that is, a compound of two of the most common elements in the cosmos, hydrogen and carbon. It has a cosmic abundance comparable with ammonia.[42] Hydrocarbons could act as a solvent over a wide range of temperatures, but would lack polarity. Isaac Asimov, the biochemist and science fiction writer, suggested in 1981 that poly-lipids could form a substitute for proteins in a non-polar solvent such as methane.[42] Lakes composed of a mixture of hydrocarbons, including methane and ethane, have been detected on the surface of Titan by the Cassini spacecraft.There is debate about the effectiveness of methane and other hydrocarbons as a solvent for life compared to water or ammonia.[48][49][50] Water is a stronger solvent than the hydrocarbons, enabling easier transport of substances in a cell.[51] However, water is also more chemically reactive, and can break down large organic molecules through hydrolysis.[48] A life-form whose solvent was a hydrocarbon would not face the threat of its biomolecules being destroyed in this way.[48] Also, the water molecule's tendency to form strong hydrogen bonds can interfere with internal hydrogen bonding in complex organic molecules.[41] Life with a hydrocarbon solvent could make more use of hydrogen bonds within its biomolecules.[48] Moreover, the strength of hydrogen bonds within biomolecules would be appropriate to a low-temperature biochemistry.[48]

Astrobiologist Chris McKay has argued, on thermodynamic grounds, that if life does exist on Titan's surface, using hydrocarbons as a solvent, it is likely also to use the more complex hydrocarbons as an energy source by reacting them with hydrogen, reducing ethane and acetylene to methane.[52] Possible evidence for this form of life on Titan was identified in 2010 by Darrell Strobel of Johns Hopkins University; a greater abundance of molecular hydrogen in the upper atmospheric layers of Titan compared to the lower layers, arguing for a downward diffusion at a rate of roughly 1025 molecules per second and disappearance of hydrogen near Titan's surface. As Strobel noted, his findings were in line with the effects Chris McKay had predicted if methanogenic life-forms were present.[51][52][53] The same year, another study showed low levels of acetylene on Titan's surface, which were interpreted by Chris McKay as consistent with the hypothesis of organisms reducing acetylene to methane.[51] While restating the biological hypothesis, McKay cautioned that other explanations for the hydrogen and acetylene findings are to be considered more likely: the possibilities of yet unidentified physical or chemical processes (e.g. a non-living surface catalyst enabling acetylene to react with hydrogen), or flaws in the current models of material flow.[54] He noted that even a non-biological catalyst effective at 95 K would in itself be a startling discovery.[54]

Azotosome

A hypothetical cell membrane termed an azotosome capable of functioning in liquid methane in Titan conditions was computer-modeled in a paper published in February 2015. Composed of acrylonitrile, a small molecule containing carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen, it is predicted to have stability and flexibility in liquid methane comparable to that of a phospholipid bilayer (the type of cell membrane possessed by all life on Earth) in liquid water.[55][56] An analysis of data obtained using the Atacama Large Millimeter / submillimeter Array (ALMA), completed in 2017, confirmed substantial amounts of acrylonitrile in Titan's atmosphere.[57][58]Hydrogen fluoride

Hydrogen fluoride (HF), like water, is a polar molecule, and due to its polarity it can dissolve many ionic compounds. Its melting point is −84 °C and its boiling point is 19.54 °C (at atmospheric pressure); the difference between the two is a little more than 100 K. HF also makes hydrogen bonds with its neighbor molecules, as do water and ammonia. It has been considered as a possible solvent for life by scientists such as Peter Sneath[59] and Carl Sagan.[40]HF is dangerous to the systems of molecules that Earth-life is made of, but certain other organic compounds, such as paraffin waxes, are stable with it.[40] Like water and ammonia, liquid hydrogen fluoride supports an acid-base chemistry. Using a solvent system definition of acidity and basicity, nitric acid functions as a base when it is added to liquid HF.[60]

However, hydrogen fluoride is cosmically rare, unlike water, ammonia, and methane.[61]

Hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is the closest chemical analog to water,[62] but is less polar and a weaker inorganic solvent.[63] Hydrogen sulfide is quite plentiful on Jupiter's moon Io, and may be in liquid form a short distance below the surface; and astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch has suggested it as a possible solvent for life there.[64] On a planet with hydrogen-sulfide oceans the source of the hydrogen sulfide could come from volcanos, in which case it could be mixed in with a bit of hydrogen fluoride, which could help dissolve minerals. Hydrogen sulfide life might use a mixture of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide as their carbon source. They might produce and live off of sulfur monoxide, which is analogous to oxygen (O2). Hydrogen sulfide, like hydrogen cyanide and ammonia, suffers from the small temperature range where it is liquid, though that, like that of hydrogen cyanide and ammonia, increases with increasing pressure.Silicon dioxide and silicates

Silicon dioxide, also known as glass, silica, or quartz, is very abundant in the universe and has a large temperature range where it is liquid. However, its melting point is 1,600 to 1,725 °C (2,912 to 3,137 °F), so it would be impossible to make organic compounds in that temperature, because all of them would decompose. Silicates are similar to silicon dioxide and some could have lower boiling points than silica. Gerald Feinberg and Robert Shapiro have suggested that molten silicate rock could serve as a liquid medium for organisms with a chemistry based on silicon, oxygen, and other elements such as aluminium.[65]Other solvents or cosolvents

Sulfuric acid (H2SO4).

- Supercritical fluids: supercritical carbon dioxide and supercritical hydrogen[66]

- Simple hydrogen compounds: hydrogen chloride[67]

- More complex compounds: sulfuric acid,[35] formamide,[36] methanol[67]

- Very-low-temperature fluids: liquid nitrogen,[37] and hydrogen[37]

- High-temperature liquids: sodium chloride[68]

A proposal has been made that life on Mars may exist and be using a mixture of water and hydrogen peroxide as its solvent.[69] A 61.2% (by weight) mix of water and hydrogen peroxide has a freezing point of −56.5 °C, and also tends to super-cool rather than crystallize. It is also hygroscopic, an advantage in a water-scarce environment.[70][71]

Supercritical carbon dioxide has been proposed as a candidate for alternative biochemistry due to its ability to selectively dissolve organic compounds and assist the functioning of enzymes and because "super-Earth"- or "super-Venus"-type planets with dense high-pressure atmospheres may be common.[66]

Other speculations

Non-green photosynthesizers

Physicists have noted that, although photosynthesis on Earth generally involves green plants, a variety of other-colored plants could also support photosynthesis, essential for most life on Earth, and that other colors might be preferred in places that receive a different mix of stellar radiation than Earth.[72][73] These studies indicate that, although blue photosynthetic plants would be less likely, yellow or red plants are plausible.[73]Variable environments

Many Earth plants and animals undergo major biochemical changes during their life cycles as a response to changing environmental conditions, for example, by having a spore or hibernation state that can be sustained for years or even millennia between more active life stages.[74] Thus, it would be biochemically possible to sustain life in environments that are only periodically consistent with life as we know it.For example, frogs in cold climates can survive for extended periods of time with most of their body water in a frozen state,[74] whereas desert frogs in Australia can become inactive and dehydrate in dry periods, losing up to 75% of their fluids, yet return to life by rapidly rehydrating in wet periods.[75] Either type of frog would appear biochemically inactive (i.e. not living) during dormant periods to anyone lacking a sensitive means of detecting low levels of metabolism.

Nonplanetary life

Dust and plasma-based

In 2007, Vadim N. Tsytovich and colleagues proposed that lifelike behaviors could be exhibited by dust particles suspended in a plasma, under conditions that might exist in space.[76][77] Computer models showed that, when the dust became charged, the particles could self-organize into microscopic helical structures, and the authors offer "a rough sketch of a possible model of the helical grain structure reproduction".Scientists who have published on this topic

Scientists who have considered possible alternatives to carbon-water biochemistry include:- Isaac Asimov (1920–1992), biochemist and science fiction writer.[42]

- William Bains, Cambridge biologist, a contributor to the journal Astrobiology.[78]

- John Baross, oceanographer and astrobiologist, who chaired a committee of scientists under the United States National Research Council that published a report on life's limiting conditions in 2007.[79] The report addresses the concern that a space agency might conduct a well-resourced search for life on other worlds "and then fail to recognize it if it is encountered".[80]

- Gerald Feinberg (1933–1992), physicist and Robert Shapiro (1935–2011), chemist, co-authors of the book Life Beyond Earth.[81][82]

- V.Axel Firsoff (1910–1981), British astronomer.[83]

- Robert A. Freitas Jr. (1952–present), specialist in nano-technology and nano-medicine; author of the book Xenology.[84][85]

- J. B. S. Haldane (1892–1964), a geneticist noted for his work on abiogenesis.[43]

- George Pimentel (1922–1989), American chemist, University of California, Berkeley.[86]

- Carl Sagan (1934–1996), astronomer,[86] science popularizer, and SETI proponent.

- Peter Sneath (1923–2011), microbiologist, author of the book Planets and Life.[59]

- Jonathan Lunine, (b. 1959) American planetary scientist and physicist

In fiction

- Alternate chirality: In Arthur C. Clarke's short story "Technical Error", there is an example of differing chirality.

- The concept of reversed chirality also figured prominently in the plot of James Blish's Star Trek novel Spock Must Die!, where a transporter experiment gone awry ends up creating a duplicate Spock who turns out to be a perfect mirror-image of the original all the way down to the atomic level.

- The eponymous organism in Michael Crichton's The Andromeda Strain is described as reproducing via the direct conversion of energy into matter.

- Silicoids: John Clark, in the introduction to the 1952 shared-world anthology The Petrified Planet, outlined the biologies of the planet Uller, with a mixture of siloxane and silicone life, and of Niflheim, where metabolism is based on hydrofluoric acid and carbon tetrafluoride.

- In the original Star Trek episode "The Devil in the Dark", a highly intelligent silicon-based creature called Horta, made almost entirely of pure rock, with eggs which take the form of silicon nodules scattered throughout the caverns and tunnels of its home planet. Subsequently, in the non-canonical Star Trek book 'The Romulan Way', another Horta is a junior officer in Starfleet.

- In Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Crystalline Entity appeared in two episodes, "Datalore" and "Silicon Avatar". This was an enormous spacefaring crystal lattice that had taken thousands of lives in its quest for energy. It was destroyed before communications could be established.

- In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Home Soil" the Enterprise investigates the sabotage of a planetary terraforming station and the death of one of its members; these events are finally attributed to a completely non-organic, solar powered, saline thriving sentient life form.

- In the 1994 The X-Files episode "Firewalker", Mulder and Scully investigate a death in a remote research base and discover that a new silicon-based fungus found in the area may be affecting and killing the researchers.

- The Orion's Arm Universe Project, an online collaborative science-fiction project, includes a number of extraterrestrial species with exotic biochemistries, including organisms based on low-temperature carbohydrate chemistry, organisms that consume and live within sulfuric acid, and organisms composed of structured magnetic flux tubes within neutron stars or gas giant cores.