The death of Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch post-Impressionist painter, occurred in the early morning of 29 July 1890, in his room at the Auberge Ravoux in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise in northern France. Van Gogh was shot in the stomach, either by himself or by others, and died two days later.

Background

Early presentiments of a premature death

As early as 1883 Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: "... as to the time I still have ahead of me for work, I think I may safely presume that my body will hold up for a certain number of years... between 6 and 10, say", "... I should plan for a period of between 5 and 10 years..." Van Gogh authority Ronald de Leeuw interprets this as van Gogh "voic[ing] the presentiment that he himself had at most another ten years of life in which to realize his ideals."

Deteriorating mental health

In 1889, van Gogh experienced a deterioration in his mental health. As a result of incidents in Arles leading to a public petition, he was admitted to a hospital. His condition improved and he was ready to be discharged by March 1889, coinciding with the wedding of his brother Theo to Johanna Bonger. However, at the last moment his resolution failed him and he confided to Frédéric Salles, who served as an unofficial chaplain to the hospital's Protestant patients, that he wanted to be confined to an asylum. At Salles' suggestion van Gogh chose an asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy. Theo originally resisted this choice, even suggesting that Vincent rejoin Paul Gauguin in Pont Aven, but was eventually won over, agreeing to pay the asylum fees (requesting the cheapest third-class accommodation). Vincent entered the asylum in early May 1889. His mental condition remained stable for a while and he was able to work en plein air, producing many of his most iconic paintings, such as The Starry Night, at this time. However at the end of July, following a trip to Arles, he suffered a serious relapse that lasted a month. He made a good recovery, only to suffer another relapse in late December 1889, and early the following January an acute relapse while delivering a portrait of Madame Ginoux to her in Arles. This last relapse, described by Jan Hulsker as his longest and saddest, lasted until March 1890. In May 1890 Vincent was discharged from the asylum (the last painting he produced at the asylum was At Eternity's Gate, an image of desolation and despair), and after spending a few days with Theo and Jo in Paris, Vincent went to live in Auvers-sur-Oise, a commune north of Paris popular with artists.

Changing mood at Auvers from May 1890

Shortly before leaving Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh told how he was suffering from his stay in the hospital: "The surroundings here are beginning to weigh me down more than I can say... I need some air, I feel overwhelmed by boredom and grief."

On arriving at Auvers, van Gogh's health was still not very good. Writing on 21 May to Theo he comments: "I can do nothing about my illness. I am suffering a little just now — the thing is that after that long seclusion the days seem like weeks to me." But by 25 May, the artist was able to report to his mother that his health had improved and that the symptoms of his disease had disappeared. His letters to his sister Wilhelmina on 5 June and to Theo and his wife Jo on about 10 June indicate a continued improvement, his nightmares almost having disappeared.

On about 12 June, he wrote to his friends Mr and Mrs Ginoux in Arles, telling them how his health had suffered at Saint-Rémy but had since improved: "But latterly I had contracted the other patients' disease to such an extent that I could not be cured of my own. The other patients' society had a bad influence on me, and in the end I was absolutely unable to understand it. Then I felt I had better try a change, and for that matter, the pleasure of seeing my brother, his family and my painter friends again has done me a lot of good, and I am feeling completely calm and normal."

Furthermore, an unsent letter to Paul Gauguin which van Gogh wrote around 17 June is quite positive about his plans for the future. After describing his recent colourful wheat studies, he explains: "I would like to paint some portraits against a very vivid yet tranquil background. There are the greens of a different quality, but of the same value, so as to form a whole of green tones, which by its vibration will make you think of the gentle rustle of the ears swaying in the breeze: it is not at all easy as a colour scheme." On 2 July, writing to his brother, van Gogh comments: "I myself am also trying to do as well as I can, but I will not conceal from you that I hardly dare count on always being in good health. And if my disease returns, you would forgive me. I still love art and life very much..."

The first sign of new problems was revealed in a letter van Gogh wrote to Theo on 10 July. He first states, "I am very well, I am working hard, have painted four studies and two drawings," but then goes on to say, "I think that we must not count on Dr Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much, so that's that... I don't know what to say. Certainly my last attack, which was terrible, was in a large measure due to the influence of the other patients." Later in the letter he adds, "For myself, I can only say at the moment that I think we all need rest — I feel I failed (in French Je me sens - raté)." In an even more despairing tone he adds: "And the prospect grows darker, I see no happy future at all."

In another letter to Theo on about 10 July, van Gogh explains: "I try to be fairly good-humoured in general, but my life too is threatened at its very root, and my step is unsteady too." He then comments on his current work: "I have painted three more large canvases. They are vast stretches of corn under troubled skies, and I did not have to go out of my way very much in order to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness." But he adds, "I'm fairly sure that these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, that is, how healthy and invigorating I find the countryside."

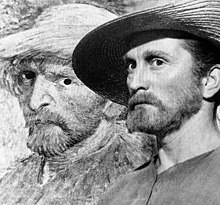

Oil on canvas, 65 cm × 54 cm

Musée d'Orsay, Paris. This may have been van Gogh's last self-portrait.

In a letter to his mother and sister written around 12 July, van Gogh again appears to be in a far more positive frame of mind: "I myself am quite absorbed in that immense plain with wheat fields up as far as the hills, boundless as the ocean, delicate yellow, delicate soft green, the delicate purple of a tilled and weeded piece of ground, with the regular speckle of the green of flowering potato plants, everything under a sky of delicate tones of blue, white, pink and violet. I am in a mood of almost too much calm, just the mood needed for painting this."

Theo recognised that Vincent was experiencing problems. In a letter dated 22 July 1890, he wrote, "I hope, my dear Vincent, that your health is good, and since you say that you write with difficulty, and don't talk about your work I am a little afraid that there is something troubling you or not going right." He went on to suggest that he consult his physician, Dr Gachet.

On 23 July, van Gogh wrote to his brother, stressing his renewed involvement in painting: "I am giving my canvases my undivided attention. I am trying to do as well as certain painters whom I have greatly loved and admired... Perhaps you will take a look at this sketch of Daubigny's garden — it is one of my most carefully thought-out canvases. I am adding a sketch of some old thatched roofs and the sketches of two size 30 canvases representing vast fields of wheat after the rain."

He returned to some of his earlier roots and subjects, and did many renditions of cottages, e.g. Houses at Auvers.

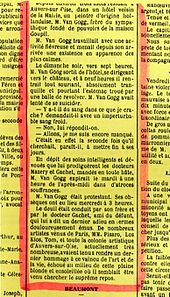

The shooting

Adeline Ravoux, the innkeeper's daughter who was only 13 at the time, clearly recalled the incidents of July 1890. In an account written when she was 76, reinforced by her father's repeated reminders, she explains how on 27 July, van Gogh left the inn after breakfast. When he had not returned by dusk, given the artist's regular habits, the family became worried. He finally arrived after nightfall, probably around 9 pm, holding his stomach. Adeline's mother asked whether there was a problem. Van Gogh started to answer with difficulty, "No, but I have..." as he climbed the stairs up to his room. Her father thought he could hear groans and found van Gogh curled up in bed. When he asked whether he was ill, van Gogh showed him a wound near his heart, explaining "I tried to kill myself." During the night, van Gogh admitted he had set out for the wheat field where he had recently been painting. During the afternoon he had shot himself with a revolver and passed out. Revived by the coolness of the evening, he had tried in vain to find the revolver to complete the act. Unsuccessful, he returned to the inn.

Adeline goes on to explain how her father sent Anton Hirschig, also a Dutch artist staying in the inn, to alert the local physician, who proved to be absent. He then called on van Gogh's friend and physician, Dr Gachet, who dressed the wound but left immediately, considering it a hopeless case. Her father and Hirsching spent the night at van Gogh's bedside. The artist sometimes smoked, sometimes groaned but remained silent almost all night long, dozing off from time to time. The following morning, two gendarmes visited the inn, questioning van Gogh about his attempted suicide. In response, he simply replied: "My body is mine and I am free to do what I want with it. Do not accuse anybody, it is I that wished to commit suicide."

As soon as the post office opened on Monday morning, Adeline's father sent a telegram to van Gogh's brother, Theo, who arrived by train during the afternoon. Adeline Ravoux explains how the two of them watched over van Gogh who fell into a coma and died at about one o'clock in the morning. (The death certificate records the time of death as 1.30 am.) In a letter to his sister Lies, Theo told of his brother's feelings just before his death: "He himself wanted to die. When I sat at his bedside and said that we would try to get him better and that we hoped that he would then be spared this kind of despair, he said, "La tristesse durera toujours" (The sadness will last forever). I understood what he wanted to say with those words."

In her memoir of December 1913, Theo's wife Johanna refers first to a letter from her husband after his arrival at Vincent's bedside: "He was glad that I came and we are together all the time... Poor fellow, very little happiness fell to his share, and no illusions are left him. The burden grows too heavy at times, he feels so alone..." And after his death, he wrote: "One of his last words was, 'I wish I could pass away like this,' and his wish was fulfilled. A few moments and all was over. He had found the rest he could not find on earth..."

Émile Bernard, an artist and friend of van Gogh, who arrived in Auvers on 30 July for the funeral, tells a slightly different story, explaining that van Gogh went out into the countryside on the Sunday evening, "left his easel against a haystack and went behind the château and fired a revolver shot at himself." He tells us how van Gogh had said that "his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity... When Dr Gachet told him that he still hoped to save his life, van Gogh replied, 'Then I'll have to do it over again.'"

The funeral

In addition to the account given by Adeline Ravoux, Émile Bernard's letter to Albert Aurier provides details of the funeral which was held in the afternoon of 30 July 1890. Van Gogh's body was set out in "the painter's room" where it was surrounded by the "halo" of his last canvases and masses of yellow flowers including dahlias and sunflowers. His easel, folding stool and brushes stood before the coffin. Among those who arrived in the room were artists Lucien Pissarro and Auguste Lauzet. The coffin was carried to the hearse at three o'clock. The company climbed the hill outside Auvers in hot sunshine, Theo and several of the others sobbing pitifully. The little cemetery with new tombstones was on a little hill above fields that were ripe for harvest. Dr Gachet, trying to suppress his tears, stammered out a few words of praise, expressing his admiration for an "honest man and a great artist... who had only two aims, art and humanity."

Controversy of Naifeh and Smith biography

In 2011, authors Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith published a biography, Van Gogh: The Life, in which they challenged the conventional account of the artist's death. In the book, Naifeh and Smith argue that it was unlikely for van Gogh to have killed himself, noting the upbeat disposition of the paintings he created immediately preceding his death; furthermore, in private correspondence, van Gogh described suicide as sinful and immoral. The authors also question how van Gogh could have traveled the mile-long (about 2 km) distance between the wheat field and the inn after sustaining the fatal stomach wound, how van Gogh could have possibly obtained a gun despite his well-known mental health problems, and why van Gogh's painting gear was never found by the police.

Naifeh and Smith developed an alternative hypothesis in which van Gogh did not commit suicide, but rather was a possible victim of accidental manslaughter or foul play. Naifeh and Smith point out that the bullet entered van Gogh's abdomen at an oblique angle, not straight as might be expected from a suicide. They claim that van Gogh was acquainted with the boys who may have shot him, one of whom was in the habit of wearing a cowboy suit, and had gone drinking with them. Naifeh said: "So you have a couple of teenagers who have a malfunctioning gun, you have a boy who likes to play cowboy, you have three people probably all of whom had too much to drink." Naifeh concluded that "accidental homicide" was "far more likely". The authors contend that art historian John Rewald visited Auvers in the 1930s, and recorded the version of events that is widely believed. The authors postulate that after he was fatally wounded, van Gogh welcomed death and believed the boys had done him a favour, hence his widely quoted deathbed remark: "Do not accuse anyone... it is I who wanted to kill myself."

On 16 October 2011, an episode of the TV news magazine 60 Minutes aired a report exploring the contention of Naifeh and Smith's biography. Some credence has been given to the theory by van Gogh experts, who cite an interview with French businessman René Secrétan recorded in 1956, in which he admitted to tormenting—but not actually shooting—the artist. Nonetheless, this new biographical account has been greeted with some skepticism.

Skeptic Joe Nickell also was not convinced and offered alternative explanations. In the July 2013 issue of the Burlington Magazine, two of the research specialists from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorp, present a theory that at the time of his death, van Gogh was in a troubled state, both personally (mentally and physically) and with his relations with his brother, Theo, and a likely candidate for suicide. They also present alternative explanations to the theories presented by Naifeh and Smith.

In 2014, at Smith and Naifeh's request, handgun expert Dr. Vincent Di Maio reviewed the forensic evidence surrounding Van Gogh's shooting. Di Maio noted that to shoot himself in the left abdomen Van Gogh would have had to have held the gun at a very awkward angle, and that there would have been black powder burns on his hands and tattooing and other marks on the skin around the wound, none of which is noted in the contemporary report. Dr Di Maio gave his conclusion that

"It is my opinion that, in all medical probability, the wound incurred by Van Gogh was not self-inflicted. In other words, he did not shoot himself."

and to which Nickell responded, unconvinced.

The 2017 film Loving Vincent drew heavily on Smith and Naifeh's theory; it is also the account presented in the 2018 film At Eternity's Gate.