| Silk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

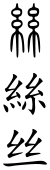

"Silk" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 絲 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 丝 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanji | 絹 | ||

| Kana | シルク | ||

Bombyx mori, Hyalophora cecropia, Antheraea pernyi, Samia cynthia.

From Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (1885–1892)

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity (sericulture). The shimmering appearance of silk is due to the triangular prism-like structure of the silk fibre, which allows silk cloth to refract incoming light at different angles, thus producing different colors.

Silk is produced by several insects; but, generally, only the silk of moth caterpillars has been used for textile manufacturing. There has been some research into other types of silk, which differ at the molecular level. Silk is mainly produced by the larvae of insects undergoing complete metamorphosis, but some insects, such as webspinners and raspy crickets, produce silk throughout their lives. Silk production also occurs in hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants), silverfish, mayflies, thrips, leafhoppers, beetles, lacewings, fleas, flies, and midges. Other types of arthropods produce silk, most notably various arachnids, such as spiders

Etymology

The word silk comes from Old English: sioloc, from Ancient Greek: σηρικός, romanized: sērikós, "silken", ultimately from the Chinese word "sī" and other Asian sources—compare Mandarin sī "silk", Manchurian sirghe, Mongolian sirkek.

History

The production of silk originated in China in the Neolithic period, although it would eventually reach other places of the world (Yangshao culture, 4th millennium BC). Silk production remained confined to China until the Silk Road opened at some point during the latter part of the 1st millennium BC, though China maintained its virtual monopoly over silk production for another thousand years.

Wild silk

Several kinds of wild silk, produced by caterpillars other than the mulberry silkworm, have been known and spun in China, South Asia, and Europe since ancient times, e.g. the production of Eri silk in Assam, India. However, the scale of production was always far smaller than for cultivated silks. There are several reasons for this: first, they differ from the domesticated varieties in colour and texture and are therefore less uniform; second, cocoons gathered in the wild have usually had the pupa emerge from them before being discovered so the silk thread that makes up the cocoon has been torn into shorter lengths; and third, many wild cocoons are covered in a mineral layer that prevents attempts to reel from them long strands of silk. Thus, the only way to obtain silk suitable for spinning into textiles in areas where commercial silks are not cultivated was by tedious and labor-intensive carding.

Some natural silk structures have been used without being unwound or spun. Spider webs were used as a wound dressing in ancient Greece and Rome, and as a base for painting from the 16th century. Caterpillar nests were pasted together to make a fabric in the Aztec Empire.

Commercial silks originate from reared silkworm pupae, which are bred to produce a white-colored silk thread with no mineral on the surface. The pupae are killed by either dipping them in boiling water before the adult moths emerge or by piercing them with a needle. These factors all contribute to the ability of the whole cocoon to be unravelled as one continuous thread, permitting a much stronger cloth to be woven from the silk. Wild silks also tend to be more difficult to dye than silk from the cultivated silkworm. A technique known as demineralizing allows the mineral layer around the cocoon of wild silk moths to be removed, leaving only variability in color as a barrier to creating a commercial silk industry based on wild silks in the parts of the world where wild silk moths thrive, such as in Africa and South America.

China

Silk use in fabric was first developed in ancient China. The earliest evidence for silk is the presence of the silk protein fibroin in soil samples from two tombs at the neolithic site Jiahu in Henan, which date back about 8,500 years. The earliest surviving example of silk fabric dates from about 3630 BC, and was used as the wrapping for the body of a child at a Yangshao culture site in Qingtaicun near Xingyang, Henan.

Legend gives credit for developing silk to a Chinese empress, Leizu (Hsi-Ling-Shih, Lei-Tzu). Silks were originally reserved for the Emperors of China for their own use and gifts to others, but spread gradually through Chinese culture and trade both geographically and socially, and then to many regions of Asia. Because of its texture and lustre, silk rapidly became a popular luxury fabric in the many areas accessible to Chinese merchants. Silk was in great demand, and became a staple of pre-industrial international trade. Silk was also used as a surface for writing, especially during the Warring States period (475-221 BCE). The fabric was light, it survived the damp climate of the Yangtze region, absorbed ink well, and provided a white background for the text. In July 2007, archaeologists discovered intricately woven and dyed silk textiles in a tomb in Jiangxi province, dated to the Eastern Zhou dynasty roughly 2,500 years ago. Although historians have suspected a long history of a formative textile industry in ancient China, this find of silk textiles employing "complicated techniques" of weaving and dyeing provides direct evidence for silks dating before the Mawangdui-discovery and other silks dating to the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD).

Silk is described in a chapter of the Fan Shengzhi shu from the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD). There is a surviving calendar for silk production in an Eastern Han (25–220 AD) document. The two other known works on silk from the Han period are lost. The first evidence of the long distance silk trade is the finding of silk in the hair of an Egyptian mummy of the 21st dynasty, c.1070 BC. The silk trade reached as far as the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Europe, and North Africa. This trade was so extensive that the major set of trade routes between Europe and Asia came to be known as the Silk Road.

The Emperors of China strove to keep knowledge of sericulture secret to maintain the Chinese monopoly. Nonetheless, sericulture reached Korea with technological aid from China around 200 BC, the ancient Kingdom of Khotan by AD 50, and India by AD 140.

In the ancient era, silk from China was the most lucrative and sought-after luxury item traded across the Eurasian continent, and many civilizations, such as the ancient Persians, benefited economically from trade.

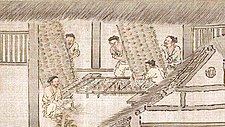

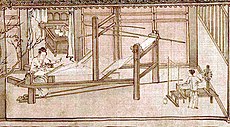

- Chinese silk making process

Northeastern India

In the northeastern state of Assam, three different types of indigenous variety of silk are produced, collectively called Assam silk: Muga, Eri, and Pat silk. Muga, the golden silk, and Eri are produced by silkworms that are native only to Assam. They have been reared since ancient times similar to other East and South-East Asian countries.

India

Silk has a long history in India. It is known as Resham in eastern and north India, and Pattu in southern parts of India. Recent archaeological discoveries in Harappa and Chanhu-daro suggest that sericulture, employing wild silk threads from native silkworm species, existed in South Asia during the time of the Indus Valley Civilisation (now in Pakistan and India) dating between 2450 BC and 2000 BC, while "hard and fast evidence" for silk production in China dates back to around 2570 BC. Shelagh Vainker, a silk expert at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who sees evidence for silk production in China "significantly earlier" than 2500–2000 BC, suggests, "people of the Indus civilization either harvested silkworm cocoons or traded with people who did, and that they knew a considerable amount about silk."

India is the second largest producer of silk in the world after China. About 97% of the raw mulberry silk comes from six Indian states, namely, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Jammu and Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, and West Bengal. North Bangalore, the upcoming site of a $20 million "Silk City" Ramanagara and Mysore, contribute to a majority of silk production in Karnataka.

In Tamil Nadu, mulberry cultivation is concentrated in the Coimbatore, Erode, Bhagalpuri, Tiruppur, Salem, and Dharmapuri districts. Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, and Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu, were the first locations to have automated silk reeling units in India.

Thailand

Silk is produced year-round in Thailand by two types of silkworms, the cultured Bombycidae and wild Saturniidae. Most production is after the rice harvest in the southern and northeastern parts of the country. Women traditionally weave silk on hand looms and pass the skill on to their daughters, as weaving is considered to be a sign of maturity and eligibility for marriage. Thai silk textiles often use complicated patterns in various colours and styles. Most regions of Thailand have their own typical silks. A single thread filament is too thin to use on its own so women combine many threads to produce a thicker, usable fiber. They do this by hand-reeling the threads onto a wooden spindle to produce a uniform strand of raw silk. The process takes around 40 hours to produce a half kilogram of silk. Many local operations use a reeling machine for this task, but some silk threads are still hand-reeled. The difference is that hand-reeled threads produce three grades of silk: two fine grades that are ideal for lightweight fabrics, and a thick grade for heavier material.

The silk fabric is soaked in extremely cold water and bleached before dyeing to remove the natural yellow coloring of Thai silk yarn. To do this, skeins of silk thread are immersed in large tubs of hydrogen peroxide. Once washed and dried, the silk is woven on a traditional hand-operated loom.

Bangladesh

The Rajshahi Division of northern Bangladesh is the hub of the country's silk industry. There are three types of silk produced in the region: mulberry, endi, and tassar. Bengali silk was a major item of international trade for centuries. It was known as Ganges silk in medieval Europe. Bengal was the leading exporter of silk between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Central Asia

The 7th century CE murals of Afrasiyab in Samarkand, Sogdiana, show a Chinese Embassy carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons to the local Sogdian ruler.

Middle East

In the Torah, a scarlet cloth item called in Hebrew "sheni tola'at" שני תולעת – literally "crimson of the worm" – is described as being used in purification ceremonies, such as those following a leprosy outbreak (Leviticus 14), alongside cedar wood and hyssop (za'atar). Eminent scholar and leading medieval translator of Jewish sources and books of the Bible into Arabic, Rabbi Saadia Gaon, translates this phrase explicitly as "crimson silk" – חריר קרמז حرير قرمز.

In Islamic teachings, Muslim men are forbidden to wear silk. Many religious jurists believe the reasoning behind the prohibition lies in avoiding clothing for men that can be considered feminine or extravagant. There are disputes regarding the amount of silk a fabric can consist of (e.g., whether a small decorative silk piece on a cotton caftan is permissible or not) for it to be lawful for men to wear, but the dominant opinion of most Muslim scholars is that the wearing of silk by men is forbidden. Modern attire has raised a number of issues, including, for instance, the permissibility of wearing silk neckties, which are masculine articles of clothing.

Ancient Mediterranean

In the Odyssey, 19.233, when Odysseus, while pretending to be someone else, is questioned by Penelope about her husband's clothing, he says that he wore a shirt "gleaming like the skin of a dried onion" (varies with translations, literal translation here) which could refer to the lustrous quality of silk fabric. Aristotle wrote of Coa vestis, a wild silk textile from Kos. Sea silk from certain large sea shells was also valued. The Roman Empire knew of and traded in silk, and Chinese silk was the most highly priced luxury good imported by them. During the reign of emperor Tiberius, sumptuary laws were passed that forbade men from wearing silk garments, but these proved ineffectual. The Historia Augusta mentions that the third-century emperor Elagabalus was the first Roman to wear garments of pure silk, whereas it had been customary to wear fabrics of silk/cotton or silk/linen blends. Despite the popularity of silk, the secret of silk-making only reached Europe around AD 550, via the Byzantine Empire. Contemporary accounts state that monks working for the emperor Justinian I smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople from China inside hollow canes. All top-quality looms and weavers were located inside the Great Palace complex in Constantinople, and the cloth produced was used in imperial robes or in diplomacy, as gifts to foreign dignitaries. The remainder was sold at very high prices.

Medieval and modern Europe

Italy was the most important producer of silk during the Medieval age. The first center to introduce silk production to Italy was the city of Catanzaro during the 11th century in the region of Calabria. The silk of Catanzaro supplied almost all of Europe and was sold in a large market fair in the port of Reggio Calabria, to Spanish, Venetian, Genovese, and Dutch merchants. Catanzaro became the lace capital of the world with a large silkworm breeding facility that produced all the laces and linens used in the Vatican. The city was world-famous for its fine fabrication of silks, velvets, damasks, and brocades.

Another notable center was the Italian city-state of Lucca which largely financed itself through silk-production and silk-trading, beginning in the 12th century. Other Italian cities involved in silk production were Genoa, Venice, and Florence. The Piedmont area of Northern Italy became a major silk producing area when water-powered silk throwing machines were developed.

The Silk Exchange in Valencia from the 15th century—where previously in 1348 also perxal (percale) was traded as some kind of silk—illustrates the power and wealth of one of the great Mediterranean mercantile cities.

Silk was produced in and exported from the province of Granada, Spain, especially the Alpujarras region, until the Moriscos, whose industry it was, were expelled from Granada in 1571.

Since the 15th century, silk production in France has been centered around the city of Lyon where many mechanic tools for mass production were first introduced in the 17th century.

James I attempted to establish silk production in England, purchasing and planting 100,000 mulberry trees, some on land adjacent to Hampton Court Palace, but they were of a species unsuited to the silk worms, and the attempt failed. In 1732 John Guardivaglio set up a silk throwing enterprise at Logwood mill in Stockport; in 1744, Burton Mill was erected in Macclesfield; and in 1753 Old Mill was built in Congleton. These three towns remained the centre of the English silk throwing industry until silk throwing was replaced by silk waste spinning. British enterprise also established silk filature in Cyprus in 1928. In England in the mid-20th century, raw silk was produced at Lullingstone Castle in Kent. Silkworms were raised and reeled under the direction of Zoe Lady Hart Dyke, later moving to Ayot St Lawrence in Hertfordshire in 1956.

During World War II, supplies of silk for UK parachute manufacture were secured from the Middle East by Peter Gaddum.

- Medieval and modern Europe

North America

Wild silk taken from the nests of native caterpillars was used by the Aztecs to make containers and as paper. Silkworms were introduced to Oaxaca from Spain in the 1530s and the region profited from silk production until the early 17th century, when the king of Spain banned export to protect Spain's silk industry. Silk production for local consumption has continued until the present day, sometimes spinning wild silk.

King James I introduced silk-growing to the British colonies in America around 1619, ostensibly to discourage tobacco planting. The Shakers in Kentucky adopted the practice.

The history of industrial silk in the United States is largely tied to several smaller urban centers in the Northeast region. Beginning in the 1830s, Manchester, Connecticut emerged as the early center of the silk industry in America, when the Cheney Brothers became the first in the United States to properly raise silkworms on an industrial scale; today the Cheney Brothers Historic District showcases their former mills. With the mulberry tree craze of that decade, other smaller producers began raising silkworms. This economy particularly gained traction in the vicinity of Northampton, Massachusetts and its neighboring Williamsburg, where a number of small firms and cooperatives emerged. Among the most prominent of these was the cooperative utopian Northampton Association for Education and Industry, of which Sojourner Truth was a member. Following the destructive Mill River Flood of 1874, one manufacturer, William Skinner, relocated his mill from Williamsburg to the then-new city of Holyoke. Over the next 50 years he and his sons would maintain relations between the American silk industry and its counterparts in Japan, and expanded their business to the point that by 1911, the Skinner Mill complex contained the largest silk mill under one roof in the world, and the brand Skinner Fabrics had become the largest manufacturer of silk satins internationally. Other efforts later in the 19th century would also bring the new silk industry to Paterson, New Jersey, with several firms hiring European-born textile workers and granting it the nickname "Silk City" as another major center of production in the United States.

World War II interrupted the silk trade from Asia, and silk prices increased dramatically. U.S. industry began to look for substitutes, which led to the use of synthetics such as nylon. Synthetic silks have also been made from lyocell, a type of cellulose fiber, and are often difficult to distinguish from real silk (see spider silk for more on synthetic silks).

Malaysia

In Terengganu, which is now part of Malaysia, a second generation of silkworm was being imported as early as 1764 for the country's silk textile industry, especially songket. However, since the 1980s, Malaysia is no longer engaged in sericulture but does plant mulberry trees.

Vietnam

In Vietnamese legend, silk appeared in the first millennium AD and is still being woven today.

Production process

The process of silk production is known as sericulture. The entire production process of silk can be divided into several steps which are typically handled by different entities. Extracting raw silk starts by cultivating the silkworms on mulberry leaves. Once the worms start pupating in their cocoons, these are dissolved in boiling water in order for individual long fibres to be extracted and fed into the spinning reel.

To produce 1 kg of silk, 104 kg of mulberry leaves must be eaten by 3000 silkworms. It takes about 5000 silkworms to make a pure silk kimono. The major silk producers are China (54%) and India (14%). Other statistics:

| Top Ten Cocoons (Reelable) Producers – 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Int $1000) | Footnote | Production (1000 kg) | Footnote |

| 978,013 | C | 290,003 | F | |

| 259,679 | C | 77,000 | F | |

| 57,332 | C | 17,000 | F | |

| 37,097 | C | 11,000 | F | |

| 20,235 | C | 6,088 | F | |

| 16,862 | C | 5,000 | F | |

| 10,117 | C | 3,000 | F | |

| 5,059 | C | 1,500 | F | |

| 3,372 | C | 1,000 | F | |

| 2,023 | C | 600 | F | |

| No symbol = official figure, F = FAO estimate,*= Unofficial figure, C = Calculated figure; Production in Int $1000 have been calculated based on 1999–2001 international prices | ||||

The environmental impact of silk production is potentially large when compared with other natural fibers. A life-cycle assessment of Indian silk production shows that the production process has a large carbon and water footprint, mainly due to the fact that it is an animal-derived fiber and more inputs such as fertilizer and water are needed per unit of fiber produced.

Properties

Physical properties

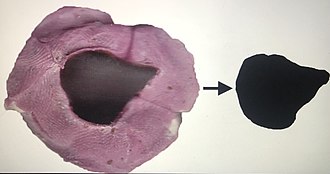

Silk fibers from the Bombyx mori silkworm have a triangular cross section with rounded corners, 5–10 μm wide. The fibroin-heavy chain is composed mostly of beta-sheets, due to a 59-mer amino acid repeat sequence with some variations. The flat surfaces of the fibrils reflect light at many angles, giving silk a natural sheen. The cross-section from other silkworms can vary in shape and diameter: crescent-like for Anaphe and elongated wedge for tussah. Silkworm fibers are naturally extruded from two silkworm glands as a pair of primary filaments (brin), which are stuck together, with sericin proteins that act like glue, to form a bave. Bave diameters for tussah silk can reach 65 μm. See cited reference for cross-sectional SEM photographs.

Silk has a smooth, soft texture that is not slippery, unlike many synthetic fibers.

Silk is one of the strongest natural fibers, but it loses up to 20% of its strength when wet. It has a good moisture regain of 11%. Its elasticity is moderate to poor: if elongated even a small amount, it remains stretched. It can be weakened if exposed to too much sunlight. It may also be attacked by insects, especially if left dirty.

One example of the durable nature of silk over other fabrics is demonstrated by the recovery in 1840 of silk garments from a wreck of 1782: 'The most durable article found has been silk; for besides pieces of cloaks and lace, a pair of black satin breeches, and a large satin waistcoat with flaps, were got up, of which the silk was perfect, but the lining entirely gone ... from the thread giving way ... No articles of dress of woollen cloth have yet been found.'

Silk is a poor conductor of electricity and thus susceptible to static cling. Silk has a high emissivity for infrared light, making it feel cool to the touch.

Unwashed silk chiffon may shrink up to 8% due to a relaxation of the fiber macrostructure, so silk should either be washed prior to garment construction, or dry cleaned. Dry cleaning may still shrink the chiffon up to 4%. Occasionally, this shrinkage can be reversed by a gentle steaming with a press cloth. There is almost no gradual shrinkage nor shrinkage due to molecular-level deformation.

Natural and synthetic silk is known to manifest piezoelectric properties in proteins, probably due to its molecular structure.

Silkworm silk was used as the standard for the denier, a measurement of linear density in fibers. Silkworm silk therefore has a linear density of approximately 1 den, or 1.1 dtex.

| Comparison of silk fibers | Linear density (dtex) | Diameter (μm) | Coeff. variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moth: Bombyx mori | 1.17 | 12.9 | 24.8% |

| Spider: Argiope aurantia | 0.14 | 3.57 | 14.8% |

Chemical properties

Silk emitted by the silkworm consists of two main proteins, sericin and fibroin, fibroin being the structural center of the silk, and serecin being the sticky material surrounding it. Fibroin is made up of the amino acids Gly-Ser-Gly-Ala-Gly-Ala and forms beta pleated sheets. Hydrogen bonds form between chains, and side chains form above and below the plane of the hydrogen bond network.

The high proportion (50%) of glycine allows tight packing. This is because glycine's R group is only a hydrogen and so is not as sterically constrained. The addition of alanine and serine makes the fibres strong and resistant to breaking. This tensile strength is due to the many interceded hydrogen bonds, and when stretched the force is applied to these numerous bonds and they do not break.

Silk resists most mineral acids, except for sulfuric acid, which dissolves it. It is yellowed by perspiration. Chlorine bleach will also destroy silk fabrics.

Variants

Regenerated silk fiber

RSF is produced by chemically dissolving silkworm cocoons, leaving their molecular structure intact. The silk fibers dissolve into tiny thread-like structures known as microfibrils. The resulting solution is extruded through a small opening, causing the microfibrils to reassemble into a single fiber. The resulting material is reportedly twice as stiff as silk.

Applications

Clothing

Silk's absorbency makes it comfortable to wear in warm weather and while active. Its low conductivity keeps warm air close to the skin during cold weather. It is often used for clothing such as shirts, ties, blouses, formal dresses, high-fashion clothes, lining, lingerie, pajamas, robes, dress suits, sun dresses, and Eastern folk costumes. For practical use, silk is excellent as clothing that protects from many biting insects that would ordinarily pierce clothing, such as mosquitoes and horseflies.

Fabrics that are often made from silk include charmeuse, habutai, chiffon, taffeta, crêpe de chine, dupioni, noil, tussah, and shantung, among others.

Furniture

Silk's attractive lustre and drape makes it suitable for many furnishing applications. It is used for upholstery, wall coverings, window treatments (if blended with another fiber), rugs, bedding, and wall hangings.

Industry

Silk had many industrial and commercial uses, such as in parachutes, bicycle tires, comforter filling, and artillery gunpowder bags.

Medicine

A special manufacturing process removes the outer sericin coating of the silk, which makes it suitable as non-absorbable surgical sutures. This process has also recently led to the introduction of specialist silk underclothing, which has been used for skin conditions including eczema. New uses and manufacturing techniques have been found for silk for making everything from disposable cups to drug delivery systems and holograms.

Biomaterial

Silk began to serve as a biomedical material for sutures in surgeries as early as the second century CE. In the past 30 years, it has been widely studied and used as a biomaterial due to its mechanical strength, biocompatibility, tunable degradation rate, ease to load cellular growth factors (for example, BMP-2), and its ability to be processed into several other formats such as films, gels, particles, and scaffolds. Silks from Bombyx mori, a kind of cultivated silkworm, are the most widely investigated silks.

Silks derived from Bombyx mori are generally made of two parts: the silk fibroin fiber which contains a light chain of 25kDa and a heavy chain of 350kDa (or 390kDa) linked by a single disulfide bond and a glue-like protein, sericin, comprising 25 to 30 percentage by weight. Silk fibroin contains hydrophobic beta sheet blocks, interrupted by small hydrophilic groups. And the beta-sheets contribute much to the high mechanical strength of silk fibers, which achieves 740 MPa, tens of times that of poly(lactic acid) and hundreds of times that of collagen. This impressive mechanical strength has made silk fibroin very competitive for applications in biomaterials. Indeed, silk fibers have found their way into tendon tissue engineering, where mechanical properties matter greatly. In addition, mechanical properties of silks from various kinds of silkworms vary widely, which provides more choices for their use in tissue engineering.

Most products fabricated from regenerated silk are weak and brittle, with only ≈1–2% of the mechanical strength of native silk fibers due to the absence of appropriate secondary and hierarchical structure,

| Source Organisms | Tensile strength

(g/den) |

Tensile modulus

(g/den) |

Breaking

strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bombyx mori | 4.3–5.2 | 84–121 | 10.0–23.4 |

| Antheraea mylitta | 2.5–4.5 | 66–70 | 26–39 |

| Philosamia cynthia ricini | 1.9–3.5 | 29–31 | 28.0–24.0 |

| Coscinocera hercules | 5 ± 1 | 87 ± 17 | 12 ± 5 |

| Hyalophora euryalus | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 59 ± 18 | 11 ± 6 |

| Rothschildia hesperis | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 71 ± 16 | 10 ± 4 |

| Eupackardia calleta | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 58 ± 18 | 12 ± 6 |

| Rothschildia lebeau | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 54 ± 14 | 16 ± 7 |

| Antheraea oculea | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 57 ± 15 | 15 ± 7 |

| Hyalophora gloveri | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 48 ± 13 | 19 ± 7 |

| Copaxa multifenestrata | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 39 ± 6 | 4 ± 3 |

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility, i.e., to what level the silk will cause an immune response, is a critical issue for biomaterials. The issue arose during its increasing clinical use. Wax or silicone is usually used as a coating to avoid fraying and potential immune responses when silk fibers serve as suture materials. Although the lack of detailed characterization of silk fibers, such as the extent of the removal of sericin, the surface chemical properties of coating material, and the process used, make it difficult to determine the real immune response of silk fibers in literature, it is generally believed that sericin is the major cause of immune response. Thus, the removal of sericin is an essential step to assure biocompatibility in biomaterial applications of silk. However, further research fails to prove clearly the contribution of sericin to inflammatory responses based on isolated sericin and sericin based biomaterials. In addition, silk fibroin exhibits an inflammatory response similar to that of tissue culture plastic in vitro when assessed with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) or lower than collagen and PLA when implant rat MSCs with silk fibroin films in vivo. Thus, appropriate degumming and sterilization will assure the biocompatibility of silk fibroin, which is further validated by in vivo experiments on rats and pigs. There are still concerns about the long-term safety of silk-based biomaterials in the human body in contrast to these promising results. Even though silk sutures serve well, they exist and interact within a limited period depending on the recovery of wounds (several weeks), much shorter than that in tissue engineering. Another concern arises from biodegradation because the biocompatibility of silk fibroin does not necessarily assure the biocompatibility of the decomposed products. In fact, different levels of immune responses and diseases have been triggered by the degraded products of silk fibroin.

Biodegradability

Biodegradability (also known as biodegradation)—the ability to be disintegrated by biological approaches, including bacteria, fungi, and cells—is another significant property of biomaterials today. Biodegradable materials can minimize the pain of patients from surgeries, especially in tissue engineering, there is no need of surgery in order to remove the scaffold implanted. Wang et al. showed the in vivo degradation of silk via aqueous 3-D scaffolds implanted into Lewis rats. Enzymes are the means used to achieve degradation of silk in vitro. Protease XIV from Streptomyces griseus and α-chymotrypsin from bovine pancreases are the two popular enzymes for silk degradation. In addition, gamma radiation, as well as cell metabolism, can also regulate the degradation of silk.

Compared with synthetic biomaterials such as polyglycolides and polylactides, silk is obviously advantageous in some aspects in biodegradation. The acidic degraded products of polyglycolides and polylactides will decrease the pH of the ambient environment and thus adversely influence the metabolism of cells, which is not an issue for silk. In addition, silk materials can retain strength over a desired period from weeks to months as needed by mediating the content of beta sheets.

Genetic modification

Genetic modification of domesticated silkworms has been used to alter the composition of the silk. As well as possibly facilitating the production of more useful types of silk, this may allow other industrially or therapeutically useful proteins to be made by silkworms.

Cultivation

Silk moths lay eggs on specially prepared paper. The eggs hatch and the caterpillars (silkworms) are fed fresh mulberry leaves. After about 35 days and 4 moltings, the caterpillars are 10,000 times heavier than when hatched and are ready to begin spinning a cocoon. A straw frame is placed over the tray of caterpillars, and each caterpillar begins spinning a cocoon by moving its head in a pattern. Two glands produce liquid silk and force it through openings in the head called spinnerets. Liquid silk is coated in sericin, a water-soluble protective gum, and solidifies on contact with the air. Within 2–3 days, the caterpillar spins about 1 mile of filament and is completely encased in a cocoon. The silk farmers then heat the cocoons to kill them, leaving some to metamorphose into moths to breed the next generation of caterpillars. Harvested cocoons are then soaked in boiling water to soften the sericin holding the silk fibers together in a cocoon shape. The fibers are then unwound to produce a continuous thread. Since a single thread is too fine and fragile for commercial use, anywhere from three to ten strands are spun together to form a single thread of silk.

Animal rights

As the process of harvesting the silk from the cocoon kills the larvae by boiling them, sericulture has been criticized by animal welfare and rights activists.

Mahatma Gandhi was critical of silk production based on the Ahimsa philosophy, which led to the promotion of cotton and Ahimsa silk, a type of wild silk made from the cocoons of wild and semi-wild silk moths.

Since silk cultivation kills silkworms, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) urges people not to buy silk items.