Western New Guinea, also known as Papua, Indonesian New Guinea, Indonesian Papua, is the western, Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea. Since the island is alternatively named as Papua, the region is also called West Papua (Indonesian: Papua Barat).

Lying to the west of Papua New Guinea and considered a part of the Australian continent, the territory is almost entirely in the Southern Hemisphere and includes the Schouten and Raja Ampat archipelagoes. The region is predominantly covered with rainforest where traditional tribes live, including the Dani of the Baliem Valley. A large proportion of the population live in or near coastal areas. The largest city is Jayapura.

In the late 1940s, territories of the Dutch East Indies became the independent country of Indonesia, with the exception of Western New Guinea. The Dutch, however, retained sovereignty over Western New Guinea (Dutch New Guinea) until the New York Agreement on 15 August 1962, which granted the region to Indonesia. The region became the province of Irian Barat (West Irian) before being renamed Irian Jaya (literally "Glorious Irian") in 1973 and Papua in 2002. The following year, a second province was created from the western part of Papua Province; this was called West Papua, with its administrative capital as Manokwari. Both provinces were granted special autonomous status by Indonesian legislation. In November 2022 three additional provinces were created from parts of Papua Province – Central Papua, Highland Papua and South Papua – while another additional province, Southwest Papua, was created from part of West Papua Province; these received the same special autonomous status as (the residual) West Papua and Papua Provinces, the latter now reduced to northern Papua and the groups of islands in Cenderawasih Bay.

In 2020, West Papua and Papua provinces had a census population of 5,437,775, the majority of whom are Papuan people; the official estimate as of mid 2022 was 5,601,888.

The official language is Indonesian, with Papuan Malay probably the most used lingua franca. Estimates of the number of local languages in the region range from 200 to over 700, with the most widely spoken including Dani, Yali, Ekari and Biak. The predominant official religion is Christianity, followed by Islam. The main industries include agriculture, fishing, oil production, and mining.

Name

Speakers align themselves with a political orientation when choosing a name for the western half of the island of New Guinea. The official name of the region is "Papua" according to International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Independence activists refer to the region as "West Papua", while Indonesian officials have also used "West Papua" to name the western province of the region since 2007. Historically, the region has had the official names of Netherlands New Guinea (1895–1962), West New Guinea or West Irian (1962–1973), Irian Jaya (1973–2002), and Papua (2002–present). The expected Indonesian translation of "Western New Guinea", Nugini Barat, is currently only used in historical contexts such as kampanye Nugini Barat "Western New Guinea campaign".

Geography

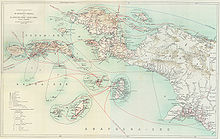

The region is 1,200 kilometres (750 miles) from east to west and 736 kilometres (457 miles) from north to south. It has an area of 412,214.61 square kilometres (159,157 square miles), which equates to approximately 22% of Indonesia's land area. The border with Papua New Guinea mostly follows the 141st meridian east, with one section defined by the Fly River.

The island of New Guinea was once part of the Australian landmass and lies on the continent of Sahul. The collision between the Indo-Australian Plate and the Pacific Plate resulted in the formation of the Maoke Mountains, which run through the centre of the region and are 600 km (373 mi) long and 100 km (62 mi) across. The range includes about ten peaks over 4,000 metres (13,000 feet), including Puncak Jaya (4,884 m or 16,024 ft), Puncak Mandala (4,760 m or 15,620 ft) and Puncak Trikora (4,750 m or 15,580 ft). This range ensures a steady supply of rain from the tropical atmosphere. The tree line is around 4,000 m (13,100 ft) and the tallest peaks feature small glaciers and are snowbound year-round. Both north and west of the central ranges, the land remains mountainous – mostly 1,000 to 2,000 metres (3,300 to 6,600 feet) high with a warm humid climate year-round. The highland areas feature alpine grasslands, jagged bare peaks, montane forests, rainforests, fast-flowing rivers, and gorges. Swamps and low-lying alluvial plains with fertile soil dominate the southeastern section around the town of Merauke. Swamps also extend 300 kilometres (190 miles) around the Asmat region.

The region has 40 major rivers, 12 lakes, and 40 islands. The Mamberamo river is the region's largest and runs through the length of Papua Province. The result is a large area of lakes and rivers known as the Lakes Plains region. The southern lowlands, habitats of which included mangrove, tidal and freshwater swamp forest and lowland rainforest, are home to populations of fishermen and gatherers such as the Asmat people. The Baliem Valley, home of the Dani people, is a tableland 1,600 m (5,250 ft) above sea level in the midst of the central mountain range.

The dry season across the region is generally between May and October; although drier in these months, rain persists throughout the year. Strong winds and rain are experienced along the north coast from November to March. However, the south coast experiences an increase in wind and rain between April and October, which is the dry season in the Merauke area, the only part of Western New Guinea to experience distinct seasons. Coastal areas are generally hot and humid, whereas the highland areas tend to be cooler.

Ecology

Lying in the Asia-Australian transition zone near Wallacea, the region's flora and fauna include Asiatic, Australian, and endemic species. The region is 75% forest and has a high degree of biodiversity. The island has an estimated 16,000 species of plants, 124 genera of which are endemic. The mountainous areas and the north are covered with dense rainforest. Highland vegetation also includes alpine grasslands, heath, pine forests, bush and scrub. The vegetation of the south coast includes mangroves and sago palms, and in the drier southeastern section, eucalypts, paperbarks, and acacias.

Marsupial species dominate the region; there are an estimated 70 marsupial species (including possums, wallabies, tree-kangaroos, and cuscus), and 180 other mammal species (including the endangered long-beaked echidna). The region is the only part of Indonesia to have kangaroos, marsupial mice, bandicoots, and ring-tailed possums. The approximately 700 bird species include cassowaries (along the southern coastal areas), bowerbirds, kingfishers, crowned pigeons, parrots, and cockatoos. Approximately 450 of these species are endemic. Birds-of-paradise can be found in Kepala Burung and Yapen. The region is also home to around 800 species of spiders, 200 of frogs, 30,000 of beetles, and 70 of bats, as well as one of the world's longest lizards (the Papuan monitor) and some of the world's largest butterflies. The waterways and wetlands of Papua provide habitat for salt and freshwater crocodiles, tree monitors, flying foxes, ospreys, and other animals, while the equatorial glacier fields remain largely unexplored.

In February 2005, a team of scientists exploring the Foja Mountains discovered numerous new species of birds, butterflies, amphibians, and plants, including a species of rhododendron that may have the largest bloom of the genus.

Environmental issues include deforestation, the spread of the introduced crab-eating macaque, which now threatens the existence of native species, and discarded copper and gold tailings from the Grasberg mine.

Flora and fauna on the Bird's Head Peninsula

The Bird's Head Peninsula, also known as the Doberai Peninsula, is covered by the Vogelkop montane rain forests ecoregion. It includes more than 22,000 km2 of montane forests at elevations of 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and higher. Over 50% of these forests are located within protected areas. There are over 300 bird species on the peninsula, of which at least 20 are unique to the ecoregion, and some live only in very restricted areas. These include the grey-banded munia, Vogelkop bowerbird, and the king bird-of-paradise.

Road construction, illegal logging, commercial agricultural expansion, and ranching potentially threaten the integrity of the ecoregion. The southeastern coast of the Bird's Head Peninsula forms part of the Teluk Cenderawasih National Park.

Administration

Western New Guinea is currently administered as six Indonesian provinces:

| Province | Customary Territory |

Area in km2 |

Capital | Regency (kabupaten) |

City (kota) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Papua | Mee Pago | 61,072.92 | Nabire | Deiyai Dogiyai Intan Jaya Mimika Nabire Paniai Puncak Puncak Jaya |

– |

| Highland Papua | La Pago | 51,213.34 | Wamena | Central Mamberamo Jayawijaya Lanny Jaya Nduga Pegunungan Bintang Tolikara Yahukimo Yalimo |

– |

| Papua | Tabi (Mamta) and Saireri | 82,680.95 | Jayapura | Biak Numfor Jayapura Keerom Mamberamo Raya Sarmi Supiori Waropen Yapen Islands |

Jayapura |

| South Papua | Anim Ha | 117,849.16 | Merauke | Asmat Boven Digoel Mappi Merauke |

– |

| Southwest Papua | Half of Bomberai | 39,122.93 | Sorong | Maybrat Raja Ampat Sorong South Sorong Tambrauw |

Sorong |

| West Papua | Rest of Bomberai and Domberai | 60,275.33 | Manokwari | Arfak Mountains Fakfak Kaimana Manokwari South Manokwari Teluk Bintuni Teluk Wondama |

– |

History

Pre-colonial history

Papuan habitation of the region is estimated to have begun between 42,000 and 48,000 years ago. Research indicates that the highlands were an early and independent center of agriculture, and show that agriculture developed gradually over several thousands of years; the banana has been cultivated in this region for at least 7,000 years.

Austronesian peoples migrating through Maritime Southeast Asia settled in the area at least 3,000 years ago, and populated especially in Cenderawasih Bay. Diverse cultures and languages have developed in situ; there are over 300 languages and two hundred additional dialects in the region (see Papuan languages, Austronesian languages, Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages).

The 14th-century Majapahit poem Nagarakretagama mentioned Wwanin or Onin and Sran as recognized territories in the east, today identified as Onin peninsula in Fakfak Regency in the western part of the larger Bomberai Peninsula south of the Bird's Head region of Western New Guinea. Wwanin or Onin was probably the oldest name in recorded history to refer to the western part of the island of New Guinea. Meanwhile Sran refer to the southern part of Bomberai Peninsula called Koiwai (modern day Kaimana Regency), another name for an old local Papuan kingdom called Sran Eman Muun, which were the predecessor of local Papuan kingdom in the area.

European conquest

In 1526–27, the Portuguese explorer Jorge de Menezes accidentally came upon the principal island in the Biak archipelago and is credited with naming it Papua, from a Malay word pepuah, for the frizzled quality of Melanesian hair. Heading east, he eventually reported the northern coast of the Bird's Head Peninsula and the Waigeo Island, and named the region Ilhas dos Papuas (Islands of Papuans).

In 1545 the Spaniard Yñigo Ortiz de Retez sailed along the north coast as far as the Mamberamo River near which he landed, naming the island Nueva Guinea. In 1606 Portuguese navigator Luís Vaz de Torres sailed in the name of Spain along the southwestern part of the island in present-day Papua, and also claimed the territory for the King of Spain.

Near the end of the sixteenth century, the Sultanate of Ternate under Sultan Baabullah (1570–1583) had influence over parts of Papua.

Dutch rule

In 1660, the Dutch recognised the Sultan of Tidore's sovereignty over New Guinea. New Guinea thus became notionally Dutch as the Dutch held power over Tidore. In 1793, Britain established a settlement near Manokwari. However, it failed. By 1824 Britain and the Netherlands agreed that the western half of the island would become part of the Dutch East Indies. In 1828 the Dutch established the settlement of Fort Du Bus at Lobo (near Kaimana), which also failed. Great Britain and Germany had recognised the Dutch claims on western New Guinea in treaties of 1885 and 1895. Dutch activity in the region remained minimal in the first half of the twentieth century. Dutch, US, and Japanese mining companies explored the area's rich oil reserves in the 1930s. In 1942, the northern coast of West New Guinea and the nearby islands were occupied by Japan. In 1944, Allied forces gained control of the region through a four-phase campaign from neighbouring Papua New Guinea. The United States constructed a headquarters for MacArthur at Hollandia (Jayapura), intended as a staging point for operations to retake the Philippines. Papuan men and resources were used to support the Allied war effort in the Pacific. After the war's end, the Dutch regained possession of the region.

Since the early twentieth century, Indonesian nationalists had sought an independent Indonesia based on all Dutch colonial possessions in the Indies, including western New Guinea. Some even founded local-based political parties, such as Indonesian Irian Independence Party (PKII) in 1946. In December 1949, the Netherlands recognised Indonesian sovereignty over the Dutch East Indies with the exception of Dutch New Guinea, the issue of which was to be discussed within a year. The Dutch successfully argued that Western New Guinea was "geographically very different" from Indonesia and the people were also very ethnically different. In an attempt to prevent Indonesia taking control of the region and to prepare the region for independence, the Dutch significantly raised development spending from its low base, began investing in Papuan education, and encouraged Papuan nationalism. A small western elite developed with a growing political awareness attuned to the idea of Papuan independence, with close links to neighbouring eastern New Guinea, which was administered by Australia. A national parliament was elected in 1961 and the Morning Star flag raised on 1 December, with independence planned in exactly 9 years' time.

Annexation and integration by Indonesia

Sukarno made the takeover of Western New Guinea a focus of his continuing struggle against Dutch imperialism and part of a broader Third World conflict with the West. Although Indonesian seaborne and paratroop incursions into the territory met with little success, the Dutch knew that a military campaign to retain the region would require protracted jungle warfare, and, unwilling to see a repeat of their futile efforts in the armed struggle for Indonesian independence in the 1940s, agreed to American mediation. The United States President John F. Kennedy wrote to the then Dutch Prime Minister Jan de Quay, encouraging the Netherlands to relinquish control of Western New Guinea to Indonesia and warning of Indonesia's potential alliance with communist powers if Sukarno was not appeased. The negotiations resulted in the UN-ratified New York Agreement of September 1962, which transferred administration to a United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) and proposed that the administration could be assumed by Indonesia until such time as a plebiscite could be organized to allow Papuans to determine whether they wanted independence or union with Indonesia.

Under the terms of the New York Agreement, all Western New Guinean men and women were to be given a plebiscite; this was to be called the Act of Free Choice. However, when the act was due to take place under the new president Suharto, the Indonesian government used a musyawarah or traditional consensus to decide the region's status. The 1,026 elders were hand-picked by the Indonesian government and many were coerced into voting for union with Indonesia. However, in the democratic culture of the Papuan people themselves at the time, there was a system known as noken, within a community in the central highlands of Papua, in which the vote is represented by the tribal chief. Soon after, as of United Nations Resolution 2504 (XXIV) the region became the 26th province of Indonesia. The 1969 Act of Free Choice is considered contentious, with even United Nations observers recognizing the elders were placed under duress and forced to vote yes.

The Free Papua Movement (OPM) has engaged in a pro-independence conflict with the Indonesian military since the 1960s. This has been in response to the initial take over of the region and multiple killings and other human rights violations by Indonesian troops, causing many West Papuans and international organisations to describe the situation in West Papua as "genocide". Rebellions occurred in remote mountainous areas in 1969, 1977, and the mid-1980s, occasionally spilling over into Papua New Guinea.

In 1980, the Trans Irian Jaya Highway, currently Trans-Papua Highway, began construction. The highway would link unconnected cities and regions across the region, which were previously only accessible by sea or, for inland areas, by air. However, some experts suggested prioritizing development of local indigenous people over infrastructure development in order to be parallel with non-Papuan migrants, who were progressively inhabiting Western New Guinea's cities at the time.

In the post-Suharto era, the national government began a process of decentralisation of the provinces, including, in December 2001, a special autonomy status for Papua province and a reinvestment into the region of 80% of the taxation receipts generated by the region, in addition of special autonomy fund.

In 2003, a new province of West Papua was created from the western regencies of Papua (province), comprising lands in the Bird's Head Peninsula and surrounding islands to its west.

In 2011, Indonesia submitted an application for membership to the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) for the two Papua provinces (as well as 3 other melanesian dominated provinces) and was granted observer status. The West Papua National Council for Liberation independence movement made an unsuccessful application for membership to the MSG in 2013 after which the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) was established in December 2014 to unite the three main political independence movements under a single umbrella organisation. In June 2015, the ULMWP was granted MSG observer status as representative of West Papuans outside the country while Indonesia was upgraded to associate member.

In 2016, at the 71st Session of the UN General Assembly, leaders of several Pacific Island countries called for UN action on alleged human rights abuses committed against Papua's indigenous Melanesians, with some leaders calling for self-determination for West Papua. Indonesia accused the countries of interfering with Indonesia's national sovereignty. In 2017, at the 72nd Session, the leaders called again for an investigation into killings and various alleged human rights abuses by Indonesian security forces.

The 2019 Papua protests began on 19 August 2019, and mainly took place across the region in response to the arrests of 43 Papuan students in Surabaya for allegedly disrespecting the Indonesian flag.

In July 2022 three additional provinces were created from parts of the existing Papua Province. The new provinces were Central Papua, Highland Papua and South Papua. In November 2022, Southwest Papua was created from the western part of West Papua Province. Thus, including the residual West Papua Province and Papua Province, there were then six provinces covering Western New Guinea.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 923,440 | — |

| 1980 | 1,173,875 | +27.1% |

| 1990 | 1,648,708 | +40.5% |

| 1995 | 1,942,627 | +17.8% |

| 2000 | 2,220,934 | +14.3% |

| 2010 | 3,593,803 | +61.8% |

| 2020 | 5,437,775 | +51.3% |

| 2021 | 5,512,275 | +1.4% |

| 2022 | 5,601,888 | +1.6% |

The population of the region was estimated to be 5,601,888 in mid 2022. The interior is predominantly populated by ethnic Papuans while coastal towns are inhabited by descendants of intermarriages between Papuans, Melanesians, and Austronesians, including the Indonesian ethnic groups. Migrants from the rest of Indonesia also tend to inhabit the coastal regions. The largest cities in the territory are Jayapura in the region's northeast, and Sorong in the northwest of the Bird's Head Peninsula. By 2022 Jayapura had a population of over 400,000 and Sorong nearly 300,000; other major towns are Timika and Nabire in Central Papua, Merauke in South Papua, and Manokwari in the northeast of the Bird's Head Peninsula, each of which had over 100,000 inhabitants in 2022.

The region is home to around 312 different tribes, including some uncontacted peoples. The Dani, from the Baliem Valley, are one of the most populous tribes of the region. The Manikom and Hatam inhabit the Anggi Lakes area, and the Kanum and Marind are from near Merauke. The semi-nomadic Asmat inhabit the mangrove and tidal river areas near Agats and are renowned for their woodcarving. Other tribes include the Amungme, Bauzi, Biak (or Byak), Korowai, Lani, Mee, Mek, Sawi, and Yali. Estimates of the number of distinct languages spoken in the region range from 200 to 700. A number of these languages are permanently disappearing.

As in Papua New Guinea and some surrounding east Indonesian provinces, a large majority of the population is Christian. In the 2010 census, 65.48% identified themselves as Protestant, 17.67% as Catholic, 15.89% as Muslim, and less than 1% as either Hindu or Buddhist. There is also a substantial practice of animism among the major religions, but this is not recorded by the census.

Haplogroups

There are 6 main Y-chromosome haplogroups in Western New Guinea; Y-chromosome haplogroup M, Y-chromosome haplogroup O, and Y-chromosome haplogroup S across the mountain highlands; meanwhile, D, C2 and C4 are of negligible numbers.

- Haplogroup M is the most frequently occurring Y-chromosome haplogroup in Western New Guinea.

- In a 2005 study of Papua New Guinea's ASPM gene variants, Mekel-Bobrov et al. found that the Papuan people have among the highest rate of the newly evolved ASPM haplogroup D, at 59.4% occurrence of the approximately 6,000-year-old allele.

- Haplogroup O is a primary descendant of haplogroup NO-M214 typical throughout the regions of East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia.

- Haplogroup S occurs in eastern Indonesia (10–20%) and Island Melanesia (~10%), but reaches greatest frequency in the highlands of Papua New Guinea (52%).

Tribal extinction

In 2012, the Tampoto tribe in Skow Mabo village, Jayapura, was on the brink of extinction, with only a single person (a man in his twenties) still living; the Dasem tribe in Waena area, Jayapura, also is near extinction, with only one family consisting of several people still alive. A decade ago, the Sebo tribe in the Kayu Pulau region, Jayapura Bay, died out. Hundreds of Papuan tribes have their own individual languages; they are unable to compete in the acculturation process with other groups, and some tribes have resisted acculturation.

Culture

Papuans have significant cultural affinities with the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea. As in Papua New Guinea, the peoples of the highlands have traditions and languages distinct from the peoples of the coast, though Papuan scholars and activists have recently detailed cultural links between coast and highlands as evidenced by close similarity of family names. In some parts of the highlands, the koteka (penis gourd) is worn by males in ceremonies. The use of the koteka as everyday dress by Dani males in Western New Guinea is still common.

A culture of inter-tribal warfare and animosity between neighboring tribes has long been present in the highlands.

Foreign journalism

The Indonesian government is very strict in giving foreign journalists permission to enter Western New Guinea, considering that this region is very vulnerable to separatist movements. As formerly in East Timor, Indonesia's former territory, the Indonesian administration takes great efforts to filter the information that gets out of Western New Guinea. However, there is no prohibition for journalists to go to the region. In 2012, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs received 11 applications for permission to cover Papua from a number of foreign media. Of 11 requests, five were approved while the other six were rejected. Meanwhile, in 2013, requests for permission to cover Papua by foreign media soared to 28. At that time, the ministry approved 21 letters of application and rejected the other seven.

The process of admitting foreign press and NGOs, which was previously complicated, began to be facilitated in 2015. Kompas.com explained that Jokowi officially revoked the ban on foreign journalists from entering Papua. According to him, Papua is the same as other regions of Indonesia. However, as of today foreign journalists are still required to apply for permission to enter Papua through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.