Absolute idealism is an ontologically monistic philosophy chiefly associated with G. W. F. Hegel and Friedrich Schelling, both of whom were German idealist philosophers in the 19th century. The label has also been attached to others such as Josiah Royce, an American philosopher who was greatly influenced by Hegel's work, and the British idealists.

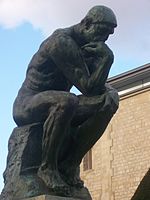

A form of idealism, absolute idealism is Hegel's account of how being is ultimately comprehensible as an all-inclusive whole (das Absolute). Hegel asserted that in order for the thinking subject (human reason or consciousness) to be able to know its object (the world) at all, there must be in some sense an identity of thought and being. Otherwise, the subject would never have access to the object and we would have no certainty about any of our knowledge of the world.

To account for the differences between thought and being, however, as well as the richness and diversity of each, the unity of thought and being cannot be expressed as the abstract identity "A=A". Absolute idealism is the attempt to demonstrate this unity using a new "speculative" philosophical method, which requires new concepts and rules of logic. According to Hegel, the absolute ground of being is essentially a dynamic, historical process of necessity that unfolds by itself in the form of increasingly complex forms of being and of consciousness, ultimately giving rise to all the diversity in the world and in the concepts with which we think and make sense of the world.

The absolute idealist position dominated philosophy in nineteenth-century Britain and Germany, while exerting significantly less influence in the United States. The absolute idealist position should be distinguished from the subjective idealism of Berkeley, the transcendental idealism of Kant, or the post-Kantian transcendental idealism (also known as critical idealism) of Fichte and of the early Schelling.

Schelling and Hegel's Absolute

Dieter Henrich characterized Hegel's conception of the absolute as follows: "The absolute is the finite to the extent to which the finite is nothing at all but negative relation to itself" (Henrich 1982, p. 82). As Bowie describes it, Hegel's system depends upon showing how each view and positing of how the world really has an internal contradiction: "This necessarily leads thought to more comprehensive ways of grasping the world, until the point where there can be no more comprehensive way because there is no longer any contradiction to give rise to it."

For Hegel, the interaction of opposites generates, in a dialectical fashion, all concepts we use in order to understand the world. Moreover, this development occurs not only in the individual mind, but also throughout history. In The Phenomenology of Spirit, for example, Hegel presents a history of human consciousness as a journey through stages of explanations of the world. Each successive explanation created problems and oppositions within itself, leading to tensions which could only be overcome by adopting a view that could accommodate these oppositions in a higher unity.

For Kant, reason was only for us, and the categories only emerged within the subject. However, for Hegel, reason is embodied, or immanent within being and the world. Reason is immanent within nature, and spirit emerges out of nature. Spirit is self-conscious reason knowing itself as reason.

The aim of Hegel was to show that we do not relate to the world as if it is other from us, but that we continue to find ourselves embedded in that world. With the realization that both mind and world are ordered according to the same rational principles, our access to the world has been made secure, a security which had been lost in Kant's proclamation that the thing-in-itself (Ding an sich) was ultimately inaccessible.

The importance of 'love' within the formulation of the absolute has also been cited by Hegel throughout his works:

The life of God — the life which the mind apprehends and enjoys as it rises to the absolute unity of all things — may be described as a play of love with itself; but this idea sinks to an edifying truism, or even to a platitude, when it does not embrace in it the earnestness, the pain, the patience, and labor, involved in the negative aspect of things.

Yet Hegel did not see Christianity per se as the route through which one reaches the absolute, but used its religious system as an historical exemplar of absolute spirit. Arriving at such an absolute was the domain of philosophy and theoretical inquiry. For Hegel speculative philosophy presented the religious content in an elevated, self-aware form.

Hegel's position is a critical transformation of the concept of the absolute advanced by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775–1854), who argued for a philosophy of Identity:

‘Absolute identity’ is, then, the link of the two aspects of being, which, on the one hand, is the universe, and, on the other, is the changing multiplicity which the knowable universe also is. Schelling insists now that “The I think, I am, is, since Descartes, the basic mistake of all knowledge; thinking is not my thinking, and being is not my being, for everything is only of God or the totality” (SW I/7, p. 148), so the I is ‘affirmed’ as a predicate of the being by which it is preceded.

Yet this absolute is different from Hegel's, which necessarily a telos or end result of the dialectic of multiplicities of consciousness throughout human history. For Schelling, the absolute is a causeless 'ground' upon which relativity (difference and similarity) can be discerned by human judgement (and thus permit 'freedom' itself) and this ground must be simultaneously not of the 'particular' world of finites but also not wholly different from them (or else there would be no commensurability with empirical reality, objects, sense data, etc. to be compared as 'relative' or otherwise):

The particular is determined in judgements, but the truth of claims about the totality cannot be proven because judgements are necessarily conditioned, whereas the totality is not. Given the relative status of the particular there must, though, be a ground which enables us to be aware of that relativity, and this ground must have a different status from the knowable world of finite particulars. At the same time, if the ground were wholly different from the world of relative particulars the problems of dualism would recur. As such the absolute is the finite, but we do not know this in the manner we know the finite. Without the presupposition of ‘absolute identity’, therefore, the evident relativity of particular knowledge becomes inexplicable, since there would be no reason to claim that a revised judgement is predicated of the same world as the preceding — now false — judgement.

In both Schelling and Hegel's 'systems' (especially the latter), the project aims towards a completion of metaphysics in such a way as to prioritize rational thinking (Vernuft), individual freedom, and philosophical and historical progress into a unity. Inspired by the system-building of previous Enlightenment thinkers like Immanuel Kant, Schelling and Hegel pushed idealism into new ontological territory (especially notable in Hegel's The Science of Logic (1812-16)), wherein a 'concept' of thought and its content are not distinguished, as Redding describes it:

While opinions divide as to how Hegel's approach to logic relates to that of Kant, it is important to grasp that for Hegel logic is not simply a science of the form of our thoughts. It is also a science of actual content as well, and as such has an ontological dimension.

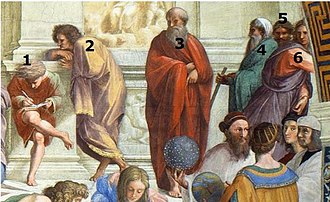

Therefore, syllogisms of logic like those espoused in the ancient world by Aristotle and crucial to the logic of Medieval philosophy, became not simply abstractions like mathematical equations but ontological necessities to describe existence itself, and therefore to be able to derive 'truth' from such existence using reason and the dialectic method of understanding. Whereas rationality was the key to completing Hegel's philosophical system, Schelling could not accept the absolutism prioritzed to Reason. Bowie elaborates on this:

Hegel's system tries to obviate the facticity of the world by understanding reason as the world's immanent self-articulation. Schelling, in contrast, insists that human reason cannot explain its own existence, and therefore cannot encompass itself and its other within a system of philosophy. We cannot, [Schelling] maintains, make sense of the manifest world by beginning with reason, but must instead begin with the contingency of being and try to make sense of it with the reason which is only one aspect of it and which cannot be explained in terms of its being a representation of the true nature of being.

Schelling's skepticism towards the prioritization of reason in the dialectic system constituting the Absolute, therefore pre-empted the vast body of philosophy that would react against Hegelianism in the modern era. Schelling's view of reason, however, was not to discard it, as would Nietzsche, but on the contrary, to use nature as its embodiment. For Schelling, reason was an organic 'striving' in nature (not just anthropocentric) and this striving was one in which the subject and the object approached an identity. Schelling saw reason as the link between spirit and the phenomenal world, as Lauer explains: "For Schelling [...] nature is not the negative of reason, to be submitted to it as reason makes the world its home, but has since its inception been turning itself into a home for reason." In Schelling's Further Presentation of My System of Philosophy (Werke Ergänzungsband I, 391-424), he argued that the comprehension of a thing is done through reason only when we see it in a whole. So Beiser (p. 17) explains:

The task of philosophical construction is then to grasp the identity of each particular with the whole of all things. To gain such knowledge we should focus upon a thing by itself, apart from its relations to anything else; we should consider it as a single, unique whole, abstracting from all its properties, which are only its partial aspects, and which relate it to other things. Just as in mathematical construction we abstract from all the accidental features of a figure (it is written with chalk, it is on a blackboard) to see it as a perfect exemplar of some universal truth, so in philosophical construction we abstract from all the specific properties of an object to see it in the absolute whole.

Hegel's doubts about intellectual intuition's ability to prove or legitimate that the particular is in identity with whole, led him to progressively formulate the system of the dialectic, now known as the Hegelian dialectic, in which concepts like the Aufhebung came to be articulated in the Phenomenology of Spirit (1807). Beiser (p. 19) summarizes the early formulation as follows:

a) Some finite concept, true of only a limited part of reality, would go beyond its limits in attempting to know all of reality. It would claim to be an adequate concept to describe the absolute because, like the absolute, it has a complete or self-sufficient meaning independent of any other concept.

b) This claim would come into conflict with the fact that the concept depends for its meaning on some other concept, having meaning only in contrast to its negation. There would then be a contradiction between its claim to independence and its de facto dependence upon another concept.

c) The only way to resolve the contradiction would be to reinterpret the claim to independence, so that it applies not just to one concept to the exclusion of the other but to the whole of both concepts. Of course, the same stages could be repeated on a higher level, and so on, until we come to the complete system of all concepts, which is alone adequate to describe the absolute.

Hegel's innovation in the history of German Idealism was for a self-consciousness or self-questioning, that would lead to a more inclusive, holistic rationality of the world. The synthesis of one concept, deemed independently true per se, with another contradictory concept (e.g. the first is in fact dependent on some other thing), leads to the history of rationality, throughout human (largely European) civilization. For the German Idealists like Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, the extrapolation or universalization of the human process of contradiction and reconciliation, whether conceptually, theoretically, or emotionally, were all movements of the universe itself. It is understandable then, why so many philosophers saw deep problems with Hegel's all-encompassing attempt at fusing anthropocentric and Eurocentric epistemology, ontology, and logic into a singular system of thought that would admit no alternative.

Neo-Hegelianism

Neo-Hegelianism is a school (or schools) of thought associated and inspired by the works of Hegel.

It refers mainly to the doctrines of an idealist school of philosophers that were prominent in Great Britain and in the United States between 1870 and 1920. The name is also sometimes applied to cover other philosophies of the period that were Hegelian in inspiration—for instance, those of Benedetto Croce and of Giovanni Gentile.

Hegelianism after Hegel

Although Hegel died in 1831, his philosophy still remains highly debated and discussed. In politics, there was a developing schism, even before his death, between right Hegelians and left Hegelians. The latter specifically took on political dimensions in the form of Marxism.

In the philosophy of religion, Hegel's influence soon became very powerful in the English-speaking world. The British school, called British idealism and partly Hegelian in inspiration, included Thomas Hill Green, Bernard Bosanquet, F. H. Bradley, William Wallace, and Edward Caird. It was importantly directed towards political philosophy and political and social policy, but also towards metaphysics and logic, as well as aesthetics.

America saw the development of a school of Hegelian thought move toward pragmatism.

German twentieth-century neo-Hegelians

In Germany there was a neo-Hegelianism (Neuhegelianismus) of the early twentieth century, partly developing out of the Neo-Kantians. Richard Kroner wrote one of its leading works, a history of German idealism from a Hegelian point of view.

Other notable neo-Hegelians

- Karl Marx (1818–1883), a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary.

- Francis Herbert Bradley (1846–1924), a British absolute idealist who adapted Hegel's Metaphysics.

- Bernard Bosanquet (1848–1923), a British idealist and speculative philosopher who had an important influence in political philosophy and public and social policy.

- Josiah Royce (1855–1916), an American defender of absolute idealism.

- Benedetto Croce (1866–1952), an Italian philosopher who defended Hegel's account on how we understand history. Croce wrote primarily on topics of aesthetics, such as artistic inspiration/intuition and personal expression.

- Giovanni Gentile (1875–1944), important philosopher within the fascist movement. Ghostwrote the first portion of "The Doctrine of Fascism".

- Alexandre Kojève (1902–1968), gave rise to a new understanding of Hegel in France during the 1930s. His lectures were attended by a small but influential group of intellectuals including Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, André Breton, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Roger Caillois, Michel Leiris, Henry Corbin, and Jean Hyppolite, and influenced Jean-Paul Sartre.

Criticisms

Exponents of analytic philosophy, which has been the dominant form of Anglo-American philosophy for most of the last century, have criticised Hegel's work as hopelessly obscure. Existentialists also criticise Hegel for ultimately choosing an essentialistic whole over the particularity of existence. Epistemologically, one of the main problems plaguing Hegel's system is how these thought determinations have bearing on reality as such. A perennial problem of his metaphysics seems to be the question of how spirit externalises itself and how the concepts it generates can say anything true about nature. At the same time, they will have to, because otherwise Hegel's system concepts would say nothing about something that is not itself a concept and the system would come down to being only an intricate game involving vacuous concepts.

Schopenhauer

Schopenhauer noted that Hegel created his absolute idealism after Kant had discredited all proofs of God's existence. The Absolute is a non-personal substitute for the concept of God. It is the one subject that perceives the universe as one object. Individuals share in parts of this perception. Since the universe exists as an idea in the mind of the Absolute, absolute idealism copies Spinoza's pantheism in which everything is in God or Nature.

Moore and Russell

Famously, G. E. Moore’s rebellion against absolutism found expression in his defense of common sense against the radically counter-intuitive conclusions of absolutism (e.g. time is unreal, change is unreal, separateness is unreal, imperfection is unreal, etc.). G. E. Moore also pioneered the use of logical analysis against the absolutists, which Bertrand Russell promulgated and used in order to begin the entire tradition of analytic philosophy with its use against the philosophies of his direct predecessors. In recounting his own mental development Russell reports, "For some years after throwing over [absolutism] I had an optimistic riot of opposite beliefs. I thought that whatever Hegel had denied must be true." (Russell in Barrett and Adkins 1962, p. 477) Also:

G.E. Moore took the lead in the rebellion, and I followed, with a sense of emancipation. [Absolutism] argued that everything common sense believes in is mere appearance. We reverted to the opposite extreme, and thought that everything is real that common sense, uninfluenced by philosophy or theology, supposes real.

— Bertrand Russell; as quoted in Klemke 2000, p.28

Pragmatism

Particularly the works of William James and F. C. S. Schiller, both founding members of pragmatism, made lifelong assaults on Absolute Idealism. James was particularly concerned with the monism that Absolute Idealism engenders, and the consequences this has for the problem of evil, free will, and moral action. Schiller, on the other hand, attacked Absolute Idealism for being too disconnected with our practical lives, and argued that its proponents failed to realize that thought is merely a tool for action rather than for making discoveries about an abstract world that fails to have any impact on us.

20th century

Absolute idealism has greatly altered the philosophical landscape. Paradoxically, (though, from a Hegelian point of view, maybe not paradoxically at all) this influence is mostly felt in the strong opposition it engendered. Both logical positivism and Analytic philosophy grew out of a rebellion against Hegelianism prevalent in England during the 19th century. Continental phenomenology, existentialism and post-modernism also seek to 'free themselves from Hegel's thought'.

Martin Heidegger, one of the leading figures of Continental philosophy in the 20th century, sought to distance himself from Hegel's work. One of Heidegger's philosophical themes in Being and Time was "overcoming metaphysics," aiming to distinguish his book from Hegelian tracts. After the 1927 publication, Heidegger's "early dismissal of them [German idealists] gives way to ever-mounting respect and critical engagement." He continued to compare and contrast his philosophy with Absolute idealism, principally due to critical comments that certain elements of this school of thought anticipated Heideggerian notions of "overcoming metaphysics."