From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Acupuncture is a form of

alternative medicine[3] in which thin needles are inserted into the body.

[4] It is a key component of

traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). TCM theory and practice are not based upon

scientific knowledge,

[5] and acupuncture is a

pseudoscience.

[6][7] There is a diverse range of acupuncture theories based on different philosophies,

[8] and techniques vary depending on the country.

[9] The method used in TCM is likely the most widespread in the United States.

[3] It is most often used for pain relief,

[10][11]

though it is also used for a wide range of other conditions.

Acupuncture is generally used only in combination with other forms of

treatment.

The conclusions of many trials and numerous

systematic reviews of acupuncture are largely inconsistent, which suggests that it is not effective.

[10][13] An overview of

Cochrane reviews found that acupuncture is not effective for a wide range of conditions.

[13] A systematic review found little evidence of acupuncture's effectiveness in treating pain.

[10] The evidence suggests that short-term treatment with acupuncture does not produce long-term benefits.

[14]

Some research results suggest acupuncture can alleviate pain, though

the majority of research suggests that acupuncture's effects are mainly

due to the

placebo effect.

[9]

A systematic review concluded that the analgesic effect of acupuncture

seemed to lack clinical relevance and could not be clearly distinguished

from bias.

[15] A

meta-analysis found that acupuncture for chronic low back pain was

cost-effective as an adjunct to standard care,

[16]

while a systematic review found insufficient evidence for the

cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic low back

pain.

[17]

Acupuncture is generally safe when done by an appropriately trained

practitioner using clean needle technique and single-use needles.

[18][19] When properly delivered, it has a low rate of mostly minor

adverse effects.

[4][18] Accidents and infections are associated with infractions of sterile technique or neglect of the practitioner.

[19] A review stated that the reports of infection transmission increased significantly in the prior decade.

[20] The most frequently reported adverse events were

pneumothorax and infections.

[10]

Since serious adverse events continue to be reported, it is recommended

that acupuncturists be trained sufficiently to reduce the risk.

[10]

Scientific investigation has not found any

histological or

physiological evidence for traditional Chinese concepts such as

qi,

meridians, and acupuncture points,

[n 1][24] and many modern practitioners no longer support the existence of life force energy (

qi) flowing through meridians, which was a major part of early belief systems.

[8][25][26] Acupuncture is believed to have originated around 100 BC in China, around the time

The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine (

Huangdi Neijing) was published,

[27] though some experts suggest it could have been practiced earlier.

[9] Over time, conflicting claims and belief systems emerged about the effect of lunar, celestial and earthly cycles,

yin and yang energies, and a body's "rhythm" on the effectiveness of treatment.

[28]

Acupuncture grew and diminished in popularity in China repeatedly,

depending on the country's political leadership and the favor of

rationalism or Western medicine.

[27] Acupuncture spread first to Korea in the 6th century AD, then to Japan through medical missionaries,

[29] and then to Europe, starting with France.

[27]

In the 20th century, as it spread to the United States and Western

countries, the spiritual elements of acupuncture that conflict with

Western beliefs were sometimes abandoned in favor of simply tapping

needles into acupuncture points.

[27][30][31]

Clinical practice

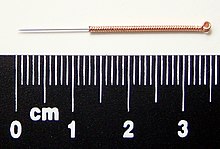

One type of acupuncture needle

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine.

[3] It is used most commonly for pain relief,

[10][11]

though it is also used to treat a wide range of conditions. The

majority of people who seek out acupuncture do so for musculoskeletal

problems, including

low back pain, shoulder stiffness, and knee pain.

[32] Acupuncture is generally only used in combination with other forms of treatment.

[12] For example,

American Society of Anesthesiologists

states it may be considered in the treatment for nonspecific,

noninflammatory low back pain only in conjunction with conventional

therapy.

[33]

Acupuncture is the insertion of thin needles into the skin.

[4] According to the

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research

(Mayo Clinic), a typical session entails lying still while

approximately five to twenty needles are inserted; for the majority of

cases, the needles will be left in place for ten to twenty minutes.

[34] It can be associated with the application of heat, pressure, or

laser light.

[4] Classically, acupuncture is individualized and based on philosophy and intuition, and not on scientific research.

[35] There is also a

non-invasive therapy developed in early 20th century Japan using an elaborate set of "needles" for the treatment of children (

shōnishin or

shōnihari).

[36][37]

Clinical practice varies depending on the country.

[9][38]

A comparison of the average number of patients treated per hour found

significant differences between China (10) and the United States (1.2).

[39] Chinese herbs are often used.

[40] There is a diverse range of acupuncture approaches, involving different philosophies.

[8]

Although various different techniques of acupuncture practice have

emerged, the method used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) seems to

be the most widely adopted in the US.

[3] Traditional acupuncture involves needle insertion,

moxibustion, and

cupping therapy,

[18] and may be accompanied by other procedures such as feeling the

pulse and other parts of the body and examining the tongue.

[3] Traditional acupuncture involves the belief that a "life force" (

qi) circulates within the body in lines called meridians.

[41] The main methods practiced in the UK are TCM and Western medical acupuncture.

[42] The term Western medical acupuncture is used to indicate an adaptation of TCM-based acupuncture which focuses less on TCM.

[41][43] The Western medical acupuncture approach involves using acupuncture after a medical diagnosis.

[41]

Limited research has compared the contrasting acupuncture systems used

in various countries for determining different acupuncture points and

thus there is no defined standard for acupuncture points.

[44]

In traditional acupuncture, the acupuncturist decides which points to

treat by observing and questioning the patient to make a diagnosis

according to the tradition used. In TCM, the four diagnostic methods

are: inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation.

Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including

analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the

absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge.

[45] Auscultation and olfaction involve listening for particular sounds such as wheezing, and observing body odor.

[45]

Inquiring involves focusing on the "seven inquiries": chills and fever;

perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination;

pain; sleep; and

menses and

leukorrhea.

[45] Palpation is focusing on feeling the body for tender

"A-shi" points and feeling the pulse.

[45]

Needles

Traditional and modern Japanese guiding tube needles

The most common mechanism of stimulation of acupuncture points

employs penetration of the skin by thin metal needles, which are

manipulated manually or the needle may be further stimulated by

electrical stimulation (electroacupuncture).

[3] Acupuncture needles are typically made of stainless steel, making them flexible and preventing them from rusting or breaking.

[46] Needles are usually disposed of after each use to prevent contamination.

[46] Reusable needles when used should be sterilized between applications.

[46][47]

Needles vary in length between 13 to 130 millimetres (0.51 to 5.12 in),

with shorter needles used near the face and eyes, and longer needles in

areas with thicker tissues; needle diameters vary from 0.16 mm

(0.006 in) to 0.46 mm (0.018 in),

[48]

with thicker needles used on more robust patients. Thinner needles may

be flexible and require tubes for insertion. The tip of the needle

should not be made too sharp to prevent breakage, although blunt needles

cause more pain.

[49]

Apart from the usual filiform needle, other needle types include three-edged needles and the Nine Ancient Needles.

[48]

Japanese acupuncturists use extremely thin needles that are used

superficially, sometimes without penetrating the skin, and surrounded by

a guide tube (a 17th-century invention adopted in China and the West).

Korean acupuncture uses copper needles and has a greater focus on the

hand.

[38]

Needling technique

Insertion

The skin is sterilized and needles are inserted, frequently with a

plastic guide tube. Needles may be manipulated in various ways,

including spinning, flicking, or moving up and down relative to the

skin. Since most pain is felt in the superficial layers of the skin, a

quick insertion of the needle is recommended.

[50] Often the needles are stimulated by hand in order to cause a dull, localized, aching sensation that is called

de qi,

as well as "needle grasp," a tugging feeling felt by the acupuncturist

and generated by a mechanical interaction between the needle and skin.

[3] Acupuncture can be painful.

[51]

The skill level of the acupuncturist may influence how painful the

needle insertion is, and a sufficiently skilled practitioner may be able

to insert the needles without causing any pain.

[50]

De-qi sensation

De-qi (

Chinese:

得气;

pinyin:

dé qì; "arrival of qi") refers to a sensation of

numbness, distension, or electrical tingling at the needling site which might radiate along the corresponding

meridian. If

de-qi can not be generated, then inaccurate location of the

acupoint,

improper depth of needle insertion, inadequate manual manipulation, or a

very weak constitution of the patient can be considered, all of which

are thought to decrease the likelihood of successful treatment. If the

de-qi

sensation does not immediately occur upon needle insertion, various

manual manipulation techniques can be applied to promote it (such as

"plucking", "shaking" or "trembling").

[52]

Once

de-qi is achieved, further techniques might be utilized which aim to "influence" the

de-qi; for example, by certain manipulation the

de-qi

sensation allegedly can be conducted from the needling site towards

more distant sites of the body. Other techniques aim at "tonifying" (

Chinese:

补;

pinyin:

bǔ) or "sedating" (

Chinese:

泄;

pinyin:

xiè)

qi.

[52] The former techniques are used in

deficiency patterns, the latter in excess patterns.

[52] De qi

is more important in Chinese acupuncture, while Western and Japanese

patients may not consider it a necessary part of the treatment.

[38]

Related practices

- Acupressure,

a non-invasive form of bodywork, uses physical pressure applied to

acupressure points by the hand or elbow, or with various devices.[53]

- Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion, the burning of cone-shaped preparations of moxa (made from dried mugwort) on or near the skin, often but not always near or on an acupuncture point. Traditionally, acupuncture was used to treat acute conditions while moxibustion was used for chronic diseases.

Moxibustion could be direct (the cone was placed directly on the skin

and allowed to burn the skin, producing a blister and eventually a

scar), or indirect (either a cone of moxa was placed on a slice of

garlic, ginger or other vegetable, or a cylinder of moxa was held above

the skin, close enough to either warm or burn it).[54]

- Cupping therapy is an ancient Chinese form of alternative medicine in which a local suction is created on the skin; practitioners believe this mobilizes blood flow in order to promote healing.[55]

- Tui na is a TCM method of attempting to stimulate the flow of qi by various bare-handed techniques that do not involve needles.[56]

- Electroacupuncture

is a form of acupuncture in which acupuncture needles are attached to a

device that generates continuous electric pulses (this has been

described as "essentially transdermal electrical nerve stimulation [TENS] masquerading as acupuncture").[57]

- Fire needle acupuncture also known as fire needling is a technique which involves quickly inserting a flame-heated needle into areas on the body.[58]

- Sonopuncture is a stimulation of the body similar to acupuncture using sound instead of needles.[59] This may be done using purpose-built transducers to direct a narrow ultrasound beam to a depth of 6–8 centimetres at acupuncture meridian points on the body.[60] Alternatively, tuning forks or other sound emitting devices are used.[61]

- Acupuncture point injection is the injection of various substances (such as drugs, vitamins or herbal extracts) into acupoints.[62]

This technique combines traditional acupuncture with injection of what

is often an effective dose of an approved pharmaceutical drug, and

proponents claim that it may be more effective than either treatment

alone, especially for the treatment of some kinds of chronic pain.

However, a 2016 review found that most published trials of the technique

were of poor value due to methodology issues and larger trials would be

needed to draw useful conclusions.[63]

- Auriculotherapy,

commonly known as ear acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, or

auriculoacupuncture, is considered to date back to ancient China. It

involves inserting needles to stimulate points on the outer ear.[64] The modern approach was developed in France during the early 1950s.[64] There is no scientific evidence that it can cure disease; the evidence of effectiveness is negligible.[64]

- Scalp acupuncture, developed in Japan, is based on reflexological considerations regarding the scalp.

- Hand acupuncture, developed in Korea, centers around assumed reflex

zones of the hand. Medical acupuncture attempts to integrate

reflexological concepts, the trigger point model, and anatomical insights (such as dermatome distribution) into acupuncture practice, and emphasizes a more formulaic approach to acupuncture point location.[65]

- Cosmetic acupuncture is the use of acupuncture in an attempt to reduce wrinkles on the face.[66]

- Bee venom acupuncture is a treatment approach of injecting purified, diluted bee venom into acupoints.[67]

- A 2006 review of veterinary acupuncture found that there is insufficient evidence to "recommend or reject acupuncture for any condition in domestic animals".[68] Rigorous evidence for complementary and alternative techniques is lacking in veterinary medicine but evidence has been growing.[69]

-

Acupressure being applied to a hand.

-

Sujichim, hand acupuncture

-

-

Effectiveness

Acupuncture has been researched extensively; as of 2013, there were almost 1,500 randomized controlled trials on

PubMed

with "acupuncture" in the title. The results of reviews of reviews of

acupuncture's effectiveness, however, have been inconclusive.

[70]

Sham acupuncture and research

It is difficult but not impossible to design rigorous research trials for acupuncture.

[71][72] Due to acupuncture's invasive nature, one of the major challenges in

efficacy research is in the design of an appropriate placebo

control group.

[73][74]

For efficacy studies to determine whether acupuncture has specific

effects, "sham" forms of acupuncture where the patient, practitioner,

and analyst are

blinded seem the most acceptable approach.

[71] Sham acupuncture uses non-penetrating needles or needling at non-acupuncture points,

[75]

e.g. inserting needles on meridians not related to the specific

condition being studied, or in places not associated with meridians.

[76]

The under-performance of acupuncture in such trials may indicate that

therapeutic effects are due entirely to non-specific effects, or that

the sham treatments are not inert, or that systematic protocols yield

less than optimal treatment.

[77][78]

A 2014

review in

Nature Reviews Cancer found that "contrary to the claimed mechanism of redirecting the flow of

qi

through meridians, researchers usually find that it generally does not

matter where the needles are inserted, how often (that is, no

dose-response effect is observed), or even if needles are actually

inserted. In other words, 'sham' or 'placebo' acupuncture generally

produces the same effects as 'real' acupuncture and, in some cases, does

better."

[79]

A 2013 meta-analysis found little evidence that the effectiveness of

acupuncture on pain (compared to sham) was modified by the location of

the needles, the number of needles used, the experience or technique of

the practitioner, or by the circumstances of the sessions.

[80]

The same analysis also suggested that the number of needles and

sessions is important, as greater numbers improved the outcomes of

acupuncture compared to non-acupuncture controls.

[80]

There has been little systematic investigation of which components of

an acupuncture session may be important for any therapeutic effect,

including needle placement and depth, type and intensity of stimulation,

and number of needles used.

[77]

The research seems to suggest that needles do not need to stimulate the

traditionally specified acupuncture points or penetrate the skin to

attain an anticipated effect (e.g. psychosocial factors).

[3]

A response to "sham" acupuncture in osteoarthritis may be used in the

elderly, but placebos have usually been regarded as deception and thus

unethical.

[81]

However, some physicians and ethicists have suggested circumstances for

applicable uses for placebos such as it might present a theoretical

advantage of an inexpensive treatment without adverse reactions or

interactions with drugs or other medications.

[81]

As the evidence for most types of alternative medicine such as

acupuncture is far from strong, the use of alternative medicine in

regular healthcare can present an ethical question.

[82]

Using the principles of

evidence-based medicine to research acupuncture is controversial, and has produced different results.

[73]

Some research suggests acupuncture can alleviate pain but the majority

of research suggests that acupuncture's effects are mainly due to

placebo.

[9] Evidence suggests that any benefits of acupuncture are short-lasting.

[14] There is insufficient evidence to support use of acupuncture compared to

mainstream medical treatments.

[83] Acupuncture is not better than mainstream treatment in the long term.

[76]

Publication bias

Publication bias is cited as a concern in the reviews of

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of acupuncture.

[57][84][85]

A 1998 review of studies on acupuncture found that trials originating

in China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan were uniformly favourable to

acupuncture, as were ten out of eleven studies conducted in Russia.

[86]

A 2011 assessment of the quality of RCTs on TCM, including acupuncture,

concluded that the methodological quality of most such trials

(including randomization, experimental control, and blinding) was

generally poor, particularly for trials published in Chinese journals

(though the quality of acupuncture trials was better than the trials

testing TCM remedies).

[87] The study also found that trials published in non-Chinese journals tended to be of higher quality.

[87] Chinese authors use more Chinese studies, which have been demonstrated to be uniformly positive.

[88]

A 2012 review of 88 systematic reviews of acupuncture published in

Chinese journals found that less than half of these reviews reported

testing for publication bias, and that the majority of these reviews

were published in journals with

impact factors of zero.

[89]

A 2015 study comparing pre-registered records of acupuncture trials

with their published results found that it was uncommon for such trials

to be registered before the trial began. This study also found that

selective reporting of results and changing outcome measures to obtain

statistically significant results was common in this literature.

[90]

Scientist and journalist

Steven Salzberg identifies acupuncture and Chinese medicine generally as a focus for "fake medical journals" such as the

Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies and

Acupuncture in Medicine.

[91]

Specific conditions

Pain

The conclusions of many trials and numerous

systematic reviews of acupuncture are largely inconsistent with each other.

[13]

A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews found that for reducing

pain, real acupuncture was no better than sham acupuncture, and

concluded that numerous reviews have shown little convincing evidence

that acupuncture is an effective treatment for reducing pain.

[10]

The same review found that neck pain was one of only four types of pain

for which a positive effect was suggested, but cautioned that the

primary studies used carried a considerable risk of bias.

[10] A 2009 overview of

Cochrane reviews found acupuncture is not effective for a wide range of conditions.

[13]

A 2014 systematic review suggests that the

nocebo effect of acupuncture is clinically relevant and that the rate of adverse events may be a gauge of the nocebo effect.

[92] According to the 2014

Miller's Anesthesia book, "when compared with placebo, acupuncture treatment has proven efficacy for relieving pain".

[44] A 2012

meta-analysis

conducted by the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration found "relatively

modest" efficiency of acupuncture (in comparison to sham) for the

treatment of four different types of

chronic pain

(back and neck pain, knee osteoarthritis, chronic headache, and

shoulder pain) and on that basis concluded that it "is more than a

placebo" and a reasonable referral option.

[93] Commenting on this meta-analysis, both

Edzard Ernst and

David Colquhoun said the results were of negligible clinical significance.

[94][95]

Edzard Ernst later stated that "I fear that, once we manage to

eliminate this bias [that operators are not blind] … we might find that

the effects of acupuncture exclusively are a placebo response."

[96]

In 2017, the same research group updated their previous meta-analysis

and again found acupuncture to be superior to sham acupuncture for

non-specific musculoskeletal pain, osteoarthritis, chronic headache, and

shoulder pain. They also found that the effects of acupuncture

decreased by about 15% after one year.

[97]

A 2010 systematic review suggested that acupuncture is more than a

placebo for commonly occurring chronic pain conditions, but the authors

acknowledged that it is still unknown if the overall benefit is

clinically meaningful or cost-effective.

[98]

A 2010 review found real acupuncture and sham acupuncture produce

similar improvements, which can only be accepted as evidence against the

efficacy of acupuncture.

[99]

The same review found limited evidence that real acupuncture and sham

acupuncture appear to produce biological differences despite similar

effects.

[99]

A 2009 systematic review and meta-analysis found that acupuncture had a

small analgesic effect, which appeared to lack any clinical importance

and could not be discerned from bias.

[15]

The same review found that it remains unclear whether acupuncture

reduces pain independent of a psychological impact of the needling

ritual.

[15]

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis found that ear acupuncture

may be effective at reducing pain within 48 hours of its use, but the

mean difference between the acupuncture and control groups was small and that "Rigorous research is needed to establish definitive evidence".

[100]

Lower back pain

A 2013 systematic review found that acupuncture may be effective for

nonspecific lower back pain, but the authors noted there were

limitations in the studies examined, such as heterogeneity in study

characteristics and low methodological quality in many studies.

[101]

A 2012 systematic review found some supporting evidence that

acupuncture was more effective than no treatment for chronic

non-specific low back pain; the evidence was conflicting comparing the

effectiveness over other treatment approaches.

[12]

A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews found that "for chronic

low back pain, individualized acupuncture is not better in reducing

symptoms than formula acupuncture or sham acupuncture with a toothpick

that does not penetrate the skin."

[10] A 2010 review found that sham acupuncture was as effective as real acupuncture for chronic low back pain.

[3]

The specific therapeutic effects of acupuncture were small, whereas its

clinically relevant benefits were mostly due to contextual and

psychosocial circumstances.

[3]

Brain imaging studies have shown that traditional acupuncture and sham

acupuncture differ in their effect on limbic structures, while at the

same time showed equivalent analgesic effects.

[3] A 2005 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against either acupuncture or

dry needling for acute low back pain.

[102]

The same review found low quality evidence for pain relief and

improvement compared to no treatment or sham therapy for chronic low

back pain only in the short term immediately after treatment.

[102]

The same review also found that acupuncture is not more effective than

conventional therapy and other alternative medicine treatments.

[102]

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that, for neck

pain, acupuncture was comparable in effectiveness to conventional

treatment, while electroacupuncture was even more effective in reducing

pain than was conventional acupuncture. The same review noted that "It

is difficult to draw conclusion [sic] because the included studies have a

high risk of bias and imprecision."

[103]

A 2015 overview of systematic reviews of variable quality showed that

acupuncture can provide short-term improvements to people with chronic

Low Back Pain.

[104] The overview said this was true when acupuncture was used either in isolation or in addition to conventional therapy.

[104] A 2017 systematic review for an

American College of Physicians

clinical practice guideline found low to moderate evidence that

acupuncture was effective for chronic low back pain, and limited

evidence that it was effective for acute low back pain. The same review

found that the strength of the evidence for both conditions was low to

moderate.

[105] Another 2017 clinical practice guideline, this one produced by the

Danish Health Authority, recommended against acupuncture for both recent-onset low back pain and

lumbar radiculopathy.

[106]

Headaches and migraines

Two separate 2016 Cochrane reviews found that acupuncture could be

useful in the prophylaxis of tension-type headaches and episodic

migraines.

[107][108]

The 2016 Cochrane review evaluating acupuncture for episodic migraine

prevention concluded that true acupuncture had a small effect beyond

sham acupuncture and found moderate-quality evidence to suggest that

acupuncture is at least similarly effective to prophylactic medications

for this purpose.

[108]

A 2012 review found that acupuncture has demonstrated benefit for the

treatment of headaches, but that safety needed to be more fully

documented in order to make any strong recommendations in support of its

use.

[109]

Arthritis pain

A 2014 review concluded that "current evidence supports the use of

acupuncture as an alternative to traditional analgesics in

osteoarthritis patients."

[110] As of 2014, a meta-analysis showed that acupuncture may help

osteoarthritis pain but it was noted that the effects were insignificant in comparison to sham needles.

[111]

A 2013 systematic review and network meta-analysis found that the

evidence suggests that acupuncture may be considered one of the more

effective physical treatments for alleviating pain due to knee

osteoarthritis in the short-term compared to other relevant physical

treatments, though much of the evidence in the topic is of poor quality

and there is uncertainty about the efficacy of many of the treatments.

[112]

A 2012 review found "the potential beneficial action of acupuncture on

osteoarthritis pain does not appear to be clinically relevant."

[76] A 2010 Cochrane review found that acupuncture shows

statistically significant

benefit over sham acupuncture in the treatment of peripheral joint

osteoarthritis; however, these benefits were found to be so small that

their

clinical significance was doubtful, and "probably due at least partially to placebo effects from incomplete blinding".

[113]

A 2013 Cochrane review found low to moderate evidence that acupuncture improves pain and stiffness in treating people with

fibromyalgia compared with no treatment and standard care.

[114] A 2012 review found "there is insufficient evidence to recommend acupuncture for the treatment of fibromyalgia."

[76]

A 2010 systematic review found a small pain relief effect that was not

apparently discernible from bias; acupuncture is not a recommendable

treatment for the management of fibromyalgia on the basis of this

review.

[115]

A 2012 review found that the effectiveness of acupuncture to treat

rheumatoid arthritis is "sparse and inconclusive."

[76] A 2005 Cochrane review concluded that acupuncture use to treat rheumatoid arthritis "has no effect on

ESR,

CRP,

pain, patient's global assessment, number of swollen joints, number of

tender joints, general health, disease activity and reduction of

analgesics."

[116]

A 2010 overview of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to

recommend acupuncture in the treatment of most rheumatic conditions,

with the exceptions of osteoarthritis, low back pain, and lateral elbow

pain.

[117]

Other joint pain

A 2014 systematic review found that although manual acupuncture was effective at relieving short-term pain when used to treat

tennis elbow, its long-term effect in relieving pain was "unremarkable".

[118]

A 2007 review found that acupuncture was significantly better than sham

acupuncture at treating chronic knee pain; the evidence was not

conclusive due to the lack of large, high-quality trials.

[119]

A 2005 Cochrane Review concluded that there is not enough evidence to

determine if acupuncture is effective as a method to treat shoulder

pain.

[120]

Post-operative pain and nausea

A 2014 overview of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to suggest that acupuncture is an effective treatment for

postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in a clinical setting.

[121] A 2013 systematic review concluded that acupuncture might be beneficial in prevention and treatment of PONV.

[122] A 2009 Cochrane review found that stimulation of the P6 acupoint on the wrist was as effective (or ineffective) as

antiemetic drugs and was associated with minimal side effects.

[121][123]

The same review found "no reliable evidence for differences in risks of

postoperative nausea or vomiting after P6 acupoint stimulation compared

to antiemetic drugs."

[123]

A 2014 overview of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to suggest that acupuncture is effective for surgical or

post-operative pain.

[121] For the use of acupuncture for post-operative pain, there was contradictory evidence.

[121]

A 2014 systematic review found supportive but limited evidence for use

of acupuncture for acute post-operative pain after back surgery.

[124] A 2014 systematic review found that while the evidence suggested acupuncture could be an effective treatment for postoperative

gastroparesis, a firm conclusion could not be reached because the trials examined were of low quality.

[125]

Pain and nausea associated with cancer and cancer treatment

A 2015 Cochrane review found that there is insufficient evidence to

determine whether acupuncture is an effective treatment for cancer pain

in adults.

[126] A 2014 systematic review published in the

Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine found that acupuncture may be effective as an adjunctive treatment to palliative care for cancer patients.

[127]

A 2013 overview of reviews published in the Journal of Multinational

Association for Supportive Care in Cancer found evidence that

acupuncture could be beneficial for people with cancer-related symptoms,

but also identified few rigorous trials and high heterogeneity between

trials.

[128]

A 2012 systematic review of randomised clinical trials published in the

same journal found that the number and quality of RCTs for using

acupuncture in the treatment of

cancer pain was too low to draw definite conclusions.

[129]

A 2014 systematic review reached inconclusive results with regard to

the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating cancer-related fatigue.

[130] A 2013 systematic review found that acupuncture is an acceptable adjunctive treatment for

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, but that further research with a low risk of bias is needed.

[131]

A 2013 systematic review found that the quantity and quality of

available RCTs for analysis were too low to draw valid conclusions for

the effectiveness of acupuncture for

cancer-related fatigue.

[132]

Sleep

A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis found that acupuncture was

"associated with a significant reduction in sleep disturbances in women

experiencing

menopause-related sleep disturbances."

[133]

Other conditions

For the following conditions, the Cochrane Collaboration or other

reviews have concluded there is no strong evidence of benefit:

alcohol dependence,

[134] allergy,

[135][136][137] Alzheimer's disease,

[138] angina pectoris,

[139] ankle sprain,

[140][141] asthma,

[142][143] attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

[144][145] autism,

[146][147] baby colic,

[148] Bell's palsy,

[149][150] cardiac arrhythmias,

[151] carpal tunnel syndrome,

[152] cerebral hemorrhage,

[153] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

[154] cocaine dependence,

[155] constipation,

[156] depression,

[157][158] diabetic

peripheral neuropathy,

[159] dysphagia after

acute stroke,

[160] drug detoxification,

[161][162] dry eye,

[163] primary

dysmenorrhoea,

[164] dyspepsia,

[165] endometriosis,

[166] enuresis,

[167] epilepsy,

[168] erectile dysfunction,

[169] glaucoma,

[170] gynaecological conditions (except possibly fertility and nausea/vomiting),

[171] acute

hordeolum,

[172] hot flashes,

[173][174][175] essential hypertension,

[176] hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in newborn babies,

in vitro fertilization (IVF),

[177] induction of childbirth,

[178] insomnia,

[179][180][181] irritable bowel syndrome,

[182] labor induction,

[183] labor pain,

[184][185] lumbar spinal stenosis,

[186] major depressive disorders in pregnant women,

[187] mumps (children),

[188] musculoskeletal disorders of the extremities,

[189] myopia,

[190] neuropathic pain,

[191] obesity,

[192][193] obstetrical conditions,

[194] opioid addiction,

[195][196] Parkinson's disease,

[197] polycystic ovary syndrome,

[198][199] posttraumatic stress disorder,

[200] premenstrual syndrome,

[201] preoperative anxiety,

[202] restless legs syndrome,

[203] schizophrenia,

[204] sensorineural hearing loss,

[205] smoking cessation,

[206] stress urinary incontinence,

[207] stroke,

[208] acute stroke,

[209] stroke rehabilitation,

[210] temporomandibular joint dysfunction,

[211][212] tennis elbow,

[213] tinnitus,

[214][215] traumatic brain injury,

[216] uremic itching,

[217] uterine fibroids,

[218] vascular dementia[219] whiplash,

[220] and

xerostomia.

[221]

Moxibustion and cupping

A 2010 overview of systematic reviews found that moxibustion was

effective for several conditions but the primary studies were of poor

quality, so there persists ample uncertainty, which limits the

conclusiveness of their findings.

[222]

Safety

Adverse events

Acupuncture is generally safe when administered by an experienced,

appropriately trained practitioner using clean-needle technique and

sterile single-use needles.

[18][19] When improperly delivered it can cause adverse effects.

[18] Accidents and infections are associated with infractions of sterile technique or neglect on the part of the practitioner.

[19] To reduce the risk of serious adverse events after acupuncture, acupuncturists should be trained sufficiently.

[10] People with serious spinal disease, such as cancer or infection, are not good candidates for acupuncture.

[3] Contraindications

to acupuncture (conditions that should not be treated with acupuncture)

include coagulopathy disorders (e.g. hemophilia and advanced liver

disease), warfarin use, severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. psychosis),

and skin infections or skin trauma (e.g. burns).

[3] Further, electroacupuncture should be avoided at the spot of implanted electrical devices (such as pacemakers).

[3]

A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews (internationally and

without language restrictions) found that serious complications

following acupuncture continue to be reported.

[10] Between 2000 and 2009, ninety-five cases of

serious adverse events, including five

deaths, were reported.

[10] Many such events are not inherent to acupuncture but are due to

malpractice of acupuncturists.

[10] This might be why such complications have not been reported in surveys of adequately-trained acupuncturists.

[10]

Most such reports originate from Asia, which may reflect the large

number of treatments performed there or a relatively higher number of

poorly trained Asian acupuncturists.

[10] Many serious adverse events were reported from developed countries.

[10]

These included Australia, Austria, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany,

Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the

UK, and the US.

[10]

The number of adverse effects reported from the UK appears particularly

unusual, which may indicate less under-reporting in the UK than other

countries.

[10] Reports included 38 cases of infections and 42 cases of organ trauma.

[10] The most frequent adverse events included

pneumothorax, and

bacterial and

viral infections.

[10]

A 2013 review found (without restrictions regarding publication date, study type or language) 295 cases of infections;

mycobacterium was the

pathogen in at least 96%.

[20] Likely sources of infection include towels, hot packs or boiling tank water, and reusing reprocessed needles.

[20]

Possible sources of infection include contaminated needles, reusing

personal needles, a person's skin containing mycobacterium, and reusing

needles at various sites in the same person.

[20]

Although acupuncture is generally considered a safe procedure, a 2013

review stated that the reports of infection transmission increased

significantly in the prior decade, including those of mycobacterium.

[20]

Although it is recommended that practitioners of acupuncture use

disposable needles, the reuse of sterilized needles is still permitted.

[20] It is also recommended that thorough control practices for preventing infection be implemented and adapted.

[20]

English-language

A 2013 systematic review of the English-language case reports found

that serious adverse events associated with acupuncture are rare, but

that acupuncture is not without risk.

[18] Between 2000 and 2011 the English-language literature from 25 countries and regions reported 294 adverse events.

[18] The majority of the reported adverse events were relatively minor, and the incidences were low.

[18] For example, a prospective survey of 34,000 acupuncture treatments

found no serious adverse events and 43 minor ones, a rate of 1.3 per

1000 interventions.

[18] Another survey found there were 7.1% minor adverse events, of which 5 were serious, amid 97,733 acupuncture patients.

[18]

The most common adverse effect observed was infection (e.g.

mycobacterium), and the majority of infections were bacterial in nature,

caused by skin contact at the needling site.

[18]

Infection has also resulted from skin contact with unsterilized

equipment or with dirty towels in an unhygienic clinical setting.

[18] Other adverse complications included five reported cases of

spinal cord injuries (e.g. migrating broken needles or needling too deeply), four brain injuries, four peripheral nerve injuries, five

heart injuries, seven other organ and tissue injuries, bilateral hand

edema,

epithelioid granuloma,

pseudolymphoma,

argyria, pustules,

pancytopenia, and scarring due to hot-needle technique.

[18]

Adverse reactions from acupuncture, which are unusual and uncommon in

typical acupuncture practice, included syncope, galactorrhoea, bilateral

nystagmus, pyoderma gangrenosum, hepatotoxicity, eruptive lichen

planus, and spontaneous needle migration.

[18]

A 2013 systematic review found 31 cases of vascular injuries caused by acupuncture, three resulting in death.

[223] Two died from pericardial tamponade and one was from an aortoduodenal fistula.

[223] The same review found vascular injuries were rare, bleeding and pseudoaneurysm were most prevalent.

[223] A 2011 systematic review (without restriction in time or language), aiming to summarize all reported case of

cardiac tamponade after acupuncture, found 26 cases resulting in 14 deaths, with little doubt about

causality in most fatal instances.

[224]

The same review concluded cardiac tamponade was a serious, usually

fatal, though theoretically avoidable complication following

acupuncture, and urged training to minimize risk.

[224]

A 2012 review found a number of adverse events were reported after acupuncture in the UK's

National Health Service (NHS) but most (95%) were not severe,

[42] though miscategorization and under-reporting may alter the total figures.

[42] From January 2009 to December 2011, 468 safety incidents were recognized within the NHS organizations.

[42]

The adverse events recorded included retained needles (31%), dizziness

(30%), loss of consciousness/unresponsive (19%), falls (4%), bruising or

soreness at needle site (2%), pneumothorax (1%) and other adverse side

effects (12%).

[42] Acupuncture practitioners should know, and be prepared to be responsible for, any substantial harm from treatments.

[42] Some acupuncture proponents argue that the long history of acupuncture suggests it is safe.

[42] However, there is an increasing literature on adverse events (e.g. spinal-cord injury).

[42]

Acupuncture seems to be safe in people getting

anticoagulants, assuming needles are used at the correct location and depth.

[225] Studies are required to verify these findings.

[225] The evidence suggests that acupuncture might be a safe option for people with allergic rhinitis.

[135]

Chinese, South Korean, and Japanese-language

A 2010 systematic review of the Chinese-language literature found

numerous acupuncture-related adverse events, including pneumothorax,

fainting,

subarachnoid hemorrhage,

and infection as the most frequent, and cardiovascular injuries,

subarachnoid hemorrhage, pneumothorax, and recurrent cerebral hemorrhage

as the most serious, most of which were due to improper technique.

[226] Between 1980 and 2009, the Chinese-language literature reported 479 adverse events.

[226] Prospective surveys show that mild, transient acupuncture-associated adverse events ranged from 6.71% to 15%.

[226] In a study with 190,924 patients, the prevalence of serious adverse events was roughly 0.024%.

[226] Another study showed a rate of adverse events requiring specific treatment of 2.2%, 4,963

incidences among 229,230 patients.

[226] Infections, mainly

hepatitis,

after acupuncture are reported often in English-language research,

though are rarely reported in Chinese-language research, making it

plausible that acupuncture-associated infections have been underreported

in China.

[226] Infections were mostly caused by poor sterilization of acupuncture needles.

[226]

Other adverse events included spinal epidural hematoma (in the

cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine), chylothorax, injuries of abdominal

organs and tissues, injuries in the neck region, injuries to the eyes,

including orbital hemorrhage, traumatic cataract, injury of the

oculomotor nerve and retinal puncture, hemorrhage to the cheeks and the

hypoglottis, peripheral motor-nerve injuries and subsequent motor

dysfunction, local allergic reactions to metal needles, stroke, and

cerebral hemorrhage after acupuncture.

[226]

A causal link between acupuncture and the adverse events cardiac

arrest, pyknolepsy, shock, fever, cough, thirst, aphonia, leg numbness,

and sexual dysfunction remains uncertain.

[226]

The same review concluded that acupuncture can be considered inherently

safe when practiced by properly trained practitioners, but the review

also stated there is a need to find effective strategies to minimize the

health risks.

[226] Between 1999 and 2010, the Republic of Korean-literature contained reports of 1104 adverse events.

[227] Between the 1980s and 2002, the Japanese-language literature contained reports of 150 adverse events.

[228]

Children and pregnancy

Although acupuncture has been practiced for thousands of years in China, its use in

pediatrics in the United States did not become common until the early 2000s. In 2007, the

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted by the

National Center For Health Statistics (NCHS) estimated that approximately 150,000 children had received acupuncture treatment for a variety of conditions.

[229]

In 2008 a study determined that the use of acupuncture-needle

treatment on children was "questionable" due to the possibility of

adverse side-effects and the pain manifestation differences in children

versus adults. The study also includes warnings against practicing

acupuncture on infants, as well as on children who are over-fatigued,

very weak, or have over-eaten.

[230]

When used on children, acupuncture is considered safe when

administered by well-trained, licensed practitioners using sterile

needles; however, a 2011 review found there was limited research to draw

definite conclusions about the overall safety of pediatric acupuncture.

[4] The same review found 279 adverse events, 25 of them serious.

[4] The adverse events were mostly mild in nature (e.g. bruising or bleeding).

[4] The prevalence of mild adverse events ranged from 10.1% to 13.5%, an estimated 168 incidences among 1,422 patients.

[4] On rare occasions adverse events were serious (e.g.

cardiac rupture or

hemoptysis); many might have been a result of substandard practice.

[4] The incidence of serious adverse events was 5 per one million, which included children and adults.

[4]

When used during pregnancy, the majority of adverse events caused by

acupuncture were mild and transient, with few serious adverse events.

[231] The most frequent mild adverse event was needling or unspecified pain, followed by bleeding.

[231]

Although two deaths (one stillbirth and one neonatal death) were

reported, there was a lack of acupuncture-associated maternal mortality.

[231]

Limiting the evidence as certain, probable or possible in the causality

evaluation, the estimated incidence of adverse events following

acupuncture in pregnant women was 131 per 10,000.

[231]

Although acupuncture is not contraindicated in pregnant women, some

specific acupuncture points are particularly sensitive to needle

insertion; these spots, as well as the

abdominal region, should be avoided during pregnancy.

[3]

Moxibustion and cupping

Four adverse events associated with moxibustion were bruising, burns

and cellulitis, spinal epidural abscess, and large superficial basal

cell carcinoma.

[18] Ten adverse events were associated with cupping.

[18] The minor ones were

keloid scarring, burns, and

bullae;

[18] the serious ones were acquired hemophilia A, stroke following cupping on the back and neck, factitious

panniculitis, reversible cardiac hypertrophy, and

iron deficiency anemia.

[18]

Cost-effectiveness

A 2013 meta-analysis found that acupuncture for chronic low back pain was

cost-effective

as a complement to standard care, but not as a substitute for standard

care except in cases where comorbid depression presented.

[16] The same meta-analysis found there was no difference between sham and non-sham acupuncture.

[16]

A 2011 systematic review found insufficient evidence for the

cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic low back

pain.

[17] A 2010 systematic review found that the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture could not be concluded.

[98] A 2012 review found that acupuncture seems to be cost-effective for some pain conditions.

[232]

Risk of forgoing conventional medical care

As with other alternative medicines, unethical or naïve practitioners

may induce patients to exhaust financial resources by pursuing

ineffective treatment.

[5][233] Professional ethics codes set by accrediting organizations such as the

National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine require practitioners to make "timely referrals to other health care professionals as may be appropriate."

[234] Stephen Barrett

states that there is a "risk that an acupuncturist whose approach to

diagnosis is not based on scientific concepts will fail to diagnose a

dangerous condition".

[235]

Conceptual basis

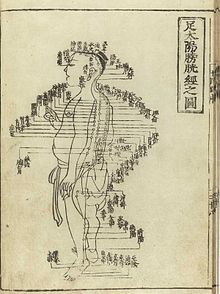

Traditional

Old Chinese medical chart of acupuncture meridians

Acupuncture is a substantial part of

traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Early acupuncture beliefs relied on concepts that are common in TCM, such as a life force energy called

qi.

[236] Qi was believed to flow from the body's primary organs (

zang-fu organs) to the "superficial" body tissues of the skin, muscles, tendons, bones, and joints, through channels called meridians.

[237] Acupuncture points where needles are inserted are mainly (but not always) found at locations along the meridians.

[238]

Acupuncture points not found along a meridian are called extraordinary

points and those with no designated site are called "A-shi" points.

[238]

In TCM, disease is generally perceived as a disharmony or imbalance in energies such as

yin, yang,

qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians, and of the interaction between the body and the environment.

[239] Therapy is based on which "pattern of disharmony" can be identified.

[240][241] For example, some diseases are believed to be caused by meridians being invaded with an excess of wind, cold, and damp.

[242] In order to determine which

pattern

is at hand, practitioners examine things like the color and shape of

the tongue, the relative strength of pulse-points, the smell of the

breath, the quality of breathing, or the sound of the voice.

[243][244] TCM and its concept of disease does not strongly differentiate between the cause and effect of symptoms.

[245]

Purported scientific basis

Scientific research has not supported the existence of

qi, meridians, or yin and yang.

[n 1][24][25] A

Nature editorial described TCM as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical

mechanism of action.

[246] Quackwatch

states that "TCM theory and practice are not based upon the body of

knowledge related to health, disease, and health care that has been

widely accepted by the scientific community. TCM practitioners disagree

among themselves about how to diagnose patients and which treatments

should go with which diagnoses. Even if they could agree, the TCM

theories are so nebulous that no amount of scientific study will enable

TCM to offer rational care."

[5]

Some modern practitioners support the use of acupuncture to treat pain, but have abandoned the use of

qi, meridians,

yin,

yang and other energies based in mysticism as explanatory frameworks.

[8][25][26] The use of

qi

as an explanatory framework has been decreasing in China, even as it

becomes more prominent during discussions of acupuncture in the US.

[247] Academic discussions of acupuncture still make reference to pseudoscientific concepts such as

qi and meridians despite the lack of scientific evidence.

[247] Many within the

scientific community consider attempts to rationalize acupuncture in science to be

quackery, pseudoscience and "theatrical placebo".

[248] Academics

Massimo Pigliucci and

Maarten Boudry describe it as a "borderlands science" lying between science and pseudoscience.

[249]

Many acupuncturists attribute pain relief to the release of

endorphins when needles penetrate, but no longer support the idea that acupuncture can affect a disease.

[26][247]

It is a generally held belief within the acupuncture community that

acupuncture points and meridians structures are special conduits for

electrical signals, but no research has established any consistent

anatomical structure or function for either acupuncture points or

meridians.

[n 1][24]

Human tests to determine whether electrical continuity was

significantly different near meridians than other places in the body

have been inconclusive.

[24]

Some studies suggest acupuncture causes a series of events within the

central nervous system,

[250] and that it is possible to inhibit acupuncture's analgesic effects with the opioid antagonist

naloxone.

[251] Mechanical deformation of the skin by acupuncture needles appears to result in the release of

adenosine.

[3] The

anti-nociceptive effect of acupuncture may be mediated by the

adenosine A1 receptor.

[252] A 2014 review in

Nature Reviews Cancer

found that since the key mouse studies that suggested acupuncture

relieves pain via the local release of adenosine, which then triggered

nearby A1 receptors "caused more tissue damage and inflammation relative

to the size of the animal in mice than in humans, such studies

unnecessarily muddled a finding that local inflammation can result in

the local release of adenosine with analgesic effect."

[79]

It has been proposed that acupuncture's effects in

gastrointestinal disorders may relate to its effects on the

parasympathetic and

sympathetic nervous system, which have been said to be the "Western medicine" equivalent of "yin and yang".

[253]

Another mechanism whereby acupuncture may be effective for

gastrointestinal dysfunction involves the promotion of gastric

peristalsis in subjects with low initial gastric motility, and

suppressing peristalsis in subjects with active initial motility.

[254] Acupuncture has also been found to exert anti-inflammatory effects, which may be mediated by the activation of the

vagus nerve and deactivation of inflammatory

macrophages.

[255] Neuroimaging studies suggest that acupuncture stimulation results in deactivation of the limbic brain areas and the

default mode network.

[256]

History

Origins

Acupuncture, along with moxibustion, is one of the oldest practices of traditional Chinese medicine.

[29] Most historians believe the practice began in China, though there are some conflicting narratives on when it originated.

[27][30]

Academics David Ramey and Paul Buell said the exact date acupuncture

was founded depends on the extent dating of ancient texts can be trusted

and the interpretation of what constitutes acupuncture.

[257]

According to an article in

Rheumatology, the first documentation of an "organized system of diagnosis and treatment" for acupuncture was in

The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine (

Huangdi Neijing) from about 100 BC.

[27] Gold and silver needles found in the tomb of

Liu Sheng

from around 100 BC are believed to be the earliest archeological

evidence of acupuncture, though it is unclear if that was their purpose.

[257] According to Plinio Prioreschi, the earliest known historical record of acupuncture is the

Shih-Chi ("Record of History"), written by a historian around 100 BC.

[28] It is believed that this text was documenting what was established practice at that time.

[27]

Alternate theories

The 5,000-year-old mummified body of

Ötzi the Iceman was found with 15 groups of tattoos,

[258]

many of which were located at points on the body where acupuncture

needles are used for abdominal or lower back problems. Evidence from the

body suggests Otzi suffered from these conditions.

[30] This has been cited as evidence that practices similar to acupuncture may have been practiced elsewhere in

Eurasia during the early

Bronze Age;

[258] however,

The Oxford Handbook of the History of Medicine calls this theory "speculative".

[31] It is considered unlikely that acupuncture was practiced before 2000 BC.

[257]

The Ötzi the Iceman's tattoo marks suggest to some experts that an

acupuncture-like treatment was previously used in Europe 5 millennia

ago.

[9]

Acupuncture may have been practiced during the

Neolithic era, near the end of the

stone age, using sharpened stones called

Bian shi.

[29]:70

Many Chinese texts from later eras refer to sharp stones called "plen",

which means "stone probe", that may have been used for acupuncture

purposes.

[29]:70

The ancient Chinese medical text, Huangdi Neijing, indicates that sharp

stones were believed at-the-time to cure illnesses at or near the

body's surface, perhaps because of the short depth a stone could

penetrate.

[29]:71 However, it is more likely that stones were used for other medical purposes, such as puncturing a growth to drain its

pus.

[27][30] The

Mawangdui texts, which are believed to be from the 2nd century BC, mention the use of pointed stones to open

abscesses, and moxibustion, but not for acupuncture.

[28]

It is also speculated that these stones may have been used for

bloodletting, due to the ancient Chinese belief that illnesses were

caused by demons within the body that could be killed or released.

[259] It is likely bloodletting was an antecedent to acupuncture.

[30]

According to historians

Lu Gwei-djen and

Joseph Needham, there is substantial evidence that acupuncture may have begun around 600 BC.

[29] Some hieroglyphs and

pictographs from that era suggests acupuncture and moxibustion were practiced.

[260]

However, historians Gwei-djen and Needham said it was unlikely a needle

could be made out of the materials available in China during this time

period.

[29]:71-72 It is possible

Bronze

was used for early acupuncture needles. Tin, copper, gold and silver

are also possibilities, though they are considered less likely, or to

have been used in fewer cases.

[29]:69 If acupuncture was practiced during the

Shang dynasty (1766 to 1122 BC), organic materials like thorns, sharpened bones, or bamboo may have been used.

[29]:70

Once methods for producing steel were discovered, it would replace all

other materials, since it could be used to create a very fine, but

sturdy needles.

[29]:74

Gwei-djen and Needham noted that all the ancient materials that could

have been used for acupuncture and which often produce archeological

evidence, such as sharpened bones, bamboo or stones, were also used for

other purposes.

[29] An article in

Rheumatology

said that the absence of any mention of acupuncture in documents found

in the tomb of Ma-Wang-Dui from 198 BC suggest that acupuncture was not

practiced by that time.

[27]

Belief systems

Several different and sometimes conflicting belief systems emerged

regarding acupuncture. This may have been the result of competing

schools of thought.

[27]

Some ancient texts referred to using acupuncture to cause bleeding,

while others mixed the ideas of blood-letting and spiritual ch'i energy. Over time, the focus shifted from blood to the concept of puncturing

specific points on the body, and eventually to balancing Yin and Yang

energies as well.

[28] According to David Ramey, no single "method or theory" was ever predominantly adopted as the standard.

[261]

At the time, scientific knowledge of medicine was not yet developed,

especially because in China dissection of the deceased was forbidden,

preventing the development of basic anatomical knowledge.

[27]

It is not certain when specific acupuncture points were introduced,

but the autobiography of Pien Chhio from around 400–500 BC references

inserting needles at designated areas.

[29] Bian Que believed there was a single acupuncture point at the top of one's skull that he called the point "of the hundred meetings."

[29]:83

Texts dated to be from 156–186 BC document early beliefs in channels of

life force energy called meridians that would later be an element in

early acupuncture beliefs.

[257]

Ramey and Buell said the "practice and theoretical underpinnings" of modern acupuncture were introduced in

The Yellow Emperor's Classic (Huangdi Neijing) around 100 BC.

[28][257] It introduced the concept of using acupuncture to manipulate the flow of life energy (

qi) in a network of meridian (channels) in the body.

[257][262]

The network concept was made up of acu-tracts, such as a line down the

arms, where it said acupoints were located. Some of the sites

acupuncturists use needles at today still have the same names as those

given to them by the

Yellow Emperor's Classic.

[29]:93 Numerous additional documents were published over the centuries introducing new acupoints.

[29]:101 By the 4th century AD, most of the acupuncture sites in use today had been named and identified.

[29]:101

Early development in China

Establishment and growth

In the first half of the 1st century AD, acupuncturists began

promoting the belief that acupuncture's effectiveness was influenced by

the time of day or night, the lunar cycle, and the season. The Science of the Yin-Yang Cycles (

Yün Chhi Hsüeh)

was a set of beliefs that curing diseases relied on the alignment of

both heavenly (thien) and earthly (ti) forces that were attuned to

cycles like that of the sun and moon.

[29]:140-141

There were several different belief systems that relied on a number of

celestial and earthly bodies or elements that rotated and only became

aligned at certain times.

According to Needham and Gwei-djen, these "arbitrary predictions" were

depicted by acupuncturists in complex charts and through a set of

special terminology.

[29]

Acupuncture needles during this period were much thicker than most

modern ones and often resulted in infection. Infection is caused by a

lack of sterilization, but at that time it was believed to be caused by

use of the wrong needle, or needling in the wrong place, or at the wrong

time.

[29]:102-103

Later, many needles were heated in boiling water, or in a flame.

Sometimes needles were used while they were still hot, creating a

cauterizing effect at the injection site.

[29]:104 Nine needles were recommended in the

Chen Chiu Ta Chheng from 1601, which may have been because of an ancient Chinese belief that nine was a magic number.

[29]:102-103

Other belief systems were based on the idea that the human body

operated on a rhythm and acupuncture had to be applied at the right

point in the rhythm to be effective.

[29]:140-141 In some cases a lack of balance between Yin and Yang were believed to be the cause of disease.

[29]:140-141

In the 1st century AD, many of the first books about acupuncture were

published and recognized acupuncturist experts began to emerge. The

Zhen Jiu Jia Yi Jing, which was published in the mid-3rd century, became the oldest acupuncture book that is still in existence in the modern era.

[29] Other books like the

Yu Kuei Chen Ching, written by the Director of Medical Services for China, were also influential during this period, but were not preserved.

[29] In the mid 7th century,

Sun Simiao

published acupuncture-related diagrams and charts that established

standardized methods for finding acupuncture sites on people of

different sizes and categorized acupuncture sites in a set of modules.

[29]

Acupuncture became more established in China as improvements in paper

led to the publication of more acupuncture books. The Imperial Medical

Service and the Imperial Medical College, which both supported

acupuncture, became more established and created medical colleges in

every province.

[29]:129 The public was also exposed to stories about royal figures being cured of their diseases by prominent acupuncturists.

[29]:129–135 By time

The Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion was published during the

Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD), most of the acupuncture practices used in the modern era had been established.

[27]

Decline

By the end of the Song dynasty (1279 AD), acupuncture had lost much of its status in China.

[263] It became rarer in the following centuries, and was associated with less prestigious professions like

alchemy,

shamanism,

midwifery and moxibustion.

[264] Additionally, by the 18th century, scientific rationality was becoming more popular than traditional superstitious beliefs.

[27] By 1757 a book documenting the history of Chinese medicine called acupuncture a "lost art".

[29]:160

Its decline was attributed in part to the popularity of prescriptions

and medications, as well as its association with the lower classes.

[265]

In 1822, the Chinese Emperor signed a decree excluding the practice of acupuncture from the Imperial Medical Institute.

[27] He said it was unfit for practice by gentlemen-scholars.

[266] In China acupuncture was increasingly associated with lower-class, illiterate practitioners.

[267]

It was restored for a time, but banned again in 1929 in favor of

science-based Western medicine. Although acupuncture declined in China

during this time period, it was also growing in popularity in other

countries.

[30]

International expansion

Acupuncture chart from

Shisi jing fahui (Expression of the Fourteen Meridians) written by Hua Shou (

fl. 1340s,

Ming dynasty). Japanese reprint by Suharaya Heisuke (Edo, 1. year Kyōhō = 1716).

Korea is believed to be the first country in Asia that acupuncture spread to outside of China.

[29] Within Korea there is a legend that acupuncture was developed by emperor

Dangun, though it is more likely to have been brought into Korea from a Chinese colonial prefecture in 514 AD.

Acupuncture use was commonplace in Korea by the 6th century. It spread to Vietnam in the 8th and 9th centuries.

[30] As Vietnam began trading with Japan and China around the 9th century, it was influenced by their acupuncture practices as well.

[27]

China and Korea sent "medical missionaries" that spread traditional

Chinese medicine to Japan, starting around 219 AD. In 553, several

Korean and Chinese citizens were appointed to re-organize medical

education in Japan and they incorporated acupuncture as part of that

system.

[29]:264

Japan later sent students back to China and established acupuncture as

one of five divisions of the Chinese State Medical Administration

System.

[29]:264-265

Acupuncture began to spread to Europe in the second half of the 17th century. Around this time the surgeon-general of the

Dutch East India Company met Japanese and Chinese acupuncture practitioners and later encouraged Europeans to further investigate it.

[29]:264-265

He published the first in-depth description of acupuncture for the

European audience and created the term "acupuncture" in his 1683 work

De Acupunctura.

[259]

France was an early adopter among the West due to the influence of

Jesuit missionaries, who brought the practice to French clinics in the

16th century.

[27] The French doctor Louis Berlioz (the father of the composer

Hector Berlioz)

is usually credited with being the first to experiment with the

procedure in Europe in 1810, before publishing his findings in 1816.

[266]

By the 19th century, acupuncture had become commonplace in many areas of the world.

[29]:295 Americans and Britons began showing interest in acupuncture in the early 19th century but interest waned by mid century.

[27] Western practitioners abandoned acupuncture's traditional beliefs in spiritual energy,

pulse diagnosis,

and the cycles of the moon, sun or the body's rhythm. Diagrams of the

flow of spiritual energy, for example, conflicted with the West's own

anatomical diagrams. It adopted a new set of ideas for acupuncture based

on tapping needles into nerves.

[27][30][31]

In Europe it was speculated that acupuncture may allow or prevent the

flow of electricity in the body, as electrical pulses were found to make

a frog's leg twitch after death.

[259]

The West eventually created a belief system based on Travell trigger

points that were believed to inhibit pain. They were in the same

locations as China's spiritually identified acupuncture points, but

under a different nomenclature.

[27] The first elaborate Western treatise on acupuncture was published in 1683 by

Willem ten Rhijne.

[268]

Modern era

In China, the popularity of acupuncture rebounded in 1949 when

Mao Zedong

took power and sought to unite China behind traditional cultural

values. It was also during this time that many Eastern medical practices

were consolidated under the name traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

[30]

New practices were adopted in the 20th century, such as using a cluster of needles,

[29]:164 electrified needles, or leaving needles inserted for up to a week.

[29]:164 A lot of emphasis developed on using acupuncture on the ear.

[29]:164 Acupuncture research organizations were founded in the 1950s and acupuncture services became available in modern hospitals.

[27] China, where acupuncture was believed to have originated, was increasingly influenced by Western medicine.

[27]

Meanwhile, acupuncture grew in popularity in the US. The US Congress

created the Office of Alternative Medicine in 1992 and the

National Institutes of Health (NIH) declared support for acupuncture for some conditions in November 1997. In 1999, the

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine was created within the NIH. Acupuncture became the most popular alternative medicine in the US.

[250]

Politicians from the

Chinese Communist Party said acupuncture was superstitious and conflicted with the party's commitment to science.

[269] Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong later reversed this position,

[269] arguing that the practice was based on scientific principles.

[270]

In 1971, a

New York Times reporter published an article on his

acupuncture experiences in China, which led to more investigation of

and support for acupuncture.

[27] The US President

Richard Nixon visited China in 1972.

[271]

During one part of the visit, the delegation was shown a patient

undergoing major surgery while fully awake, ostensibly receiving

acupuncture rather than

anesthesia.

[271] Later it was found that the patients selected for the surgery had both a high

pain tolerance and received heavy indoctrination before the operation; these demonstration cases were also frequently receiving

morphine surreptitiously through an

intravenous drip that observers were told contained only fluids and nutrients.

[271] One patient receiving

open heart surgery while awake was ultimately found to have received a combination of three powerful sedatives as well as large injections of a

local anesthetic into the wound.

[57] After the

National Institute of Health expressed support for acupuncture for a limited number of conditions, adoption in the US grew further.

[27] In 1972 the first legal acupuncture center in the US was established in Washington DC

[272] and in 1973 the American

Internal Revenue Service allowed acupuncture to be deducted as a medical expense.

[273]

In 2006, a

BBC documentary

Alternative Medicine

filmed a patient undergoing open heart surgery allegedly under

acupuncture-induced anesthesia. It was later revealed that the patient

had been given a cocktail of anesthetics.

[274][275]

In 2010,

UNESCO inscribed "acupuncture and

moxibustion of traditional Chinese medicine" on the

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List following China's nomination.

[276]

Adoption

Acupuncture is popular in China,